The Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre is the name given to the 1929 murder in Chicago of seven men of the North Side gang during the Prohibition Era.[2]

It happened on February 14, and resulted from the struggle between the Irish American gang and the South Side Italian gang led by Al Capone to take control of organized crime in the city.[3]

Former members of the Egan’s Rats gang were suspected of a significant role in the incident, assisting Capone.

History

At 10:30 a.m. on February 14, 1929, seven men were murdered at the garage at 2122 North Clark Street,[4][5] in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Chicago’s North Side.

They were shot by four men using weapons that included two Thompson submachine guns. Two of the shooters were dressed as uniformed policemen, while the others wore suits, ties, overcoats and hats.

Witnesses saw the “police” leading the other men at gunpoint out of the garage after the shooting.

The victims included five members of George “Bugs” Moran‘s North Side Gang. Moran’s second-in-command, and brother-in-law, Albert Kachellek (alias James Clark), was killed along with Adam Heyer, the gang’s bookkeeper and business manager, Albert Weinshank, who managed several cleaning and dyeing operations for Moran, and gang enforcers Frank Gusenberg and Peter Gusenberg.

Two collaborators were also shot: Reinhardt H. Schwimmer, a former optician turned gambler and gang associate, and John May, an occasional mechanic for the Moran gang.

When real Chicago police officers arrived at the scene, one of the victims, Frank Gusenberg was still alive. He was taken to the hospital, where doctors stabilized him for a short time. Police tried to question Gusenberg.

Asked who shot him, Gusenberg, who had sustained fourteen bullet wounds, replied “No one shot me.” He died three hours later.[6]

The massacre was allegedly planned by the organization led by Al Capone to eliminate George “Bugs” Moran, the boss of the long-established North Side Gang.

The former boss of the North Side Gang, Dion O’Banion, had been murdered by four gunmen in his flower shop on North State Street in 1924.[7] After the murder of O’Banion, each successive leader of the North Siders was also killed, allegedly by various members or associates of the Capone organization.

Several factors contributed to the timing of the plan to kill George “Bugs” Moran. Earlier in the year, North Sider Frank Gusenberg and his brother Peter unsuccessfully attempted to murder Jack McGurn.

The North Side Gang was complicit in the murders of Pasqualino “Patsy” Lolordo and Antonio “The Scourge” Lombardo. Both had been presidents of the Unione Siciliana, the local Mafia, and close associates of Capone.

Moran and Capone had been vying for control of the lucrative Chicago bootlegging trade, and Bugs Moran had been moving in on several of Capone’s enterprises.

Moran was muscling in on a Capone-run dog track in the Chicago suburbs and he had taken over several saloons that were run by Capone, insisting they were in his territory.

The plan was to lure Bugs Moran to the SMC Cartage warehouse on North Clark Street on February 14, 1929. The intent was to kill Moran, and perhaps two or three of his lieutenants.

It is usually assumed that the North Siders were lured to the garage with the promise of a stolen, cut-rate shipment of whiskey, supplied by Detroit’s Purple Gang, which was associated with Capone.

The Gusenberg brothers were supposed to drive two empty trucks to Detroit that day to pick up two loads of stolen Canadian whiskey.

All of the victims, with the exception of John May, were dressed in their best clothes, as was customary for the North Siders and other gangsters at the time.

On St. Valentine’s Day, most of the Moran gang had already arrived at the warehouse by approximately 10:30 a.m. Moran was not there, having left his Parkway Hotel apartment late.

As Moran and one of his men, Ted Newberry, approached the rear of the warehouse from a side street, they saw a police car approach the building.

They immediately turned and retraced their steps, going to a nearby coffee shop. They encountered another gang member, Henry Gusenberg, on the street.

Henry was warned and turned back. Willie Marks, also a North Side Gang member, spotted the police car on his way to the garage.

He ducked into a doorway and jotted down the license number before leaving the neighborhood.

Capone’s lookouts likely mistook one of Moran’s men for Moran himself – probably Albert Weinshank, who was the same height and build.

That morning the physical similarity between the two men was enhanced by their dress: both happened to be wearing the same color overcoats and hats.

Witnesses outside the garage saw a Cadillac sedan pull to a stop in front of the garage. Four men, two dressed in police uniform, emerged and walked inside.

The two fake police officers, carrying shotguns, entered the rear portion of the garage and found members of Moran’s gang and two gang collaborators, Reinhart Schwimmer and John May, who was fixing one of the trucks.

The “police officers” then ordered the men to line up against the wall.

The two “police officers” then signaled to the pair in civilian clothes who had accompanied them. Two of the killers opened fire with Thompson sub-machine guns, one with a 20-round box magazine and the other a 50-round drum.

They were thorough, spraying their victims left and right, even continuing to fire after all seven had hit the floor. The seven men were ripped apart in the volley.

Two shotgun blasts afterward all but obliterated the faces of John May and James Clark, according to the coroner’s report.

To give the appearance that everything was under control, the men in street clothes came out with their hands up, prodded by the two uniformed police officers.

Inside the garage, the only survivors in the warehouse were Highball (May’s dog) and Frank Gusenberg. Despite fourteen bullet wounds, he was still conscious, but died three hours later, refusing to utter a word about the identities of the killers.

The Valentine’s Day Massacre set off a public outcry that posed a problem for all mob bosses.[8]

Victims[edit]

- Peter Gusenberg, a frontline enforcer for the Moran organizations.

- Frank Gusenberg, the brother of Peter Gusenberg and also an enforcer.

- Albert Kachellek (alias “James Clark”), Moran’s second-in-command.

- Adam Heyer, the bookkeeper and business manager of the Moran gang.

- Reinhardt Schwimmer, an optician who had abandoned his practice to gamble on horse racing and associated with the gang.

- Albert Weinshank, who managed several cleaning and dyeing operations for Moran. His resemblance to Moran, including the clothes he was wearing, is what allegedly set the massacre in motion before Moran actually arrived.[9]

- John May, an occasional car mechanic for the Moran gang.[9]

Investigation[edit]

Since it was common knowledge that Moran was hijacking Capone’s Detroit-based liquor shipments, police focused their attention on Detroit’s predominantly Jewish Purple Gang.

Mug shots of Purple members George Lewis, Eddie Fletcher, Phil Keywell and his younger brother Harry, were picked out by landladies Mrs. Doody and Mrs. Orvidson, who had taken in three men as roomers ten days before the massacre; their rooming houses were directly across the street from the Clark Street garage.

Later, these women wavered in their identification, and Fletcher, Lewis, and Harry Keywell were all questioned and cleared by Chicago Police. Nevertheless, the Keywell brothers (and by extension the Purple Gang) would remain ensnared in the massacre case for all time.

Many also believed what the killers wanted them to believe – that the police did it.

February 22, police were called to the scene of a garage fire on Wood Street where a 1927 Cadillac Sedan was found disassembled and partially burned.

It was determined that the car had been used by the killers. The engine number was traced to a Michigan Avenue dealer, who had sold the car to a James Morton of Los Angeles.

The garage had been rented by a man calling himself Frank Rogers, who gave his address as 1859 West North Avenue – which happened to be the address of the Circus Café, operated by Claude Maddox, a former St. Louis gangster with ties to the Capone organization, the Purple Gang, and a St. Louis gang called Egan’s Rats.

Police could not turn up any information about persons named James Morton or Frank Rogers. But they had a definite lead on one of the killers. Just minutes before the killings, a truck driver named Elmer Lewis had turned a corner only a block away from 2122 North Clark and sideswiped what he took to be a police car.

He told police later that he stopped immediately but was waved away by the uniformed driver, whom he noticed was missing a front tooth. The same description of the car’s driver was also given by the president of the Board of Education, H. Wallace Caldwell, who had also witnessed the accident.

Police knew that this description could be none other than a former member of Egan’s Rats, Fred ‘Killer’ Burke; Burke and a close companion, James Ray, were well known to wear police uniforms whenever on a robbery spree.

Burke was also a fugitive, under indictment for robbery and murder in Ohio. Police also suggested that Joseph Lolordo could have been one of the killers, because of his brother Pasqualino’s recent murder by the North Side Gang.

Police then announced that they suspected Capone gunmen John Scalise and Albert Anselmi, as well as Jack McGurn himself, and Frank Rio, a Capone bodyguard. Police eventually charged McGurn and Scalise with the massacre. John Scalise, along with Anselmi and Joseph ‘Hop Toad’ Giunta, were murdered by Capone in May 1929, after Capone learned about their plan to kill him, and before he went to trial.

The murder charges against Jack McGurn were finally dropped because of a lack of evidence, and he was just charged with a violation of the Mann Act: he took his girlfriend, Louise Rolfe, who was also the main witness against him and became known as the “Blonde Alibi”, across state lines to marry.

The case stagnated until December 14, 1929, when the Berrien County, Michigan Sheriff’s Department raided the St. Joseph, Michigan bungalow of “Frederick Dane”, the registered owner of a vehicle driven by Fred “Killer” Burke.

Burke had been drinking that night, rear-ended another vehicle and drove off. Patrolman Charles Skelly pursued, finally forcing Burke off the road.

As Skelly hopped on the running board he was shot three times and died of his wounds later that night. The car was found wrecked and abandoned just outside St. Joseph and traced to Fred Dane.

By this time police photos confirmed that Dane was in fact Fred Burke, wanted by the Chicago police for his participation in the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

When police raided Burke’s bungalow, they found a large trunk containing a bullet-proof vest, almost $320,000 in bondsrecently stolen from a Wisconsin bank, two Thompson submachine guns, pistols, two shotguns, and thousands of rounds of ammunition. St. Joseph authorities immediately notified the Chicago police, who requested that both machine guns be brought there at once.

Through the then relatively new science of forensic ballistics, both weapons were determined to have been used in the massacre – and that one of Burke’s Tommy guns had also been used to murder New York mobster Frankie Yale (who participated in O’Banion’s murder) a year and a half earlier. Unfortunately, no further concrete evidence would surface in the massacre case.

Burke would be captured over a year later on a Missouri farm. As the case against him in the murder of Officer Skelly was strongest, he was tried in Michigan and subsequently sentenced to life imprisonment. Burke died in prison in 1940.

Bolton revelations[edit]

On January 8, 1935, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents surrounded a Chicago apartment building at 3920 North Pine Grove, looking for the remaining members of the Barker Gang.

A brief shootout erupted, resulting in the death of bank robber Russell Gibson. Taken into custody were Doc Barker, Byron Bolton, and two women.

While interrogating agents got nothing out of Barker, Bolton (a hitherto obscure criminal) proved to be a “geyser of information”, as one crime historian called him.

Bolton, a former Navy machine-gunner and associate of Egan’s Rats, had been the valet of the Chicago hit man Fred Goetz.

Bolton was privy to many of the Barker Gang’s crimes and pinpointed the Florida hideout of Ma and Freddie Barker (both of whom were killed in a shootout with the FBI a week later).

Bolton claimed to have taken part in the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre with Goetz, Fred Burke, and several others.

Because the FBI had no jurisdiction in a state murder case, they kept Bolton’s revelations confidential, until the Chicago American newspaper reported a second-hand version of the bank robber’s confession.

The newspaper declared that the crime had been “solved”, despite being stonewalled by J. Edgar Hoover and the Bureau, who did not want any part of the massacre case. Garbled versions of Bolton’s story went out in the national media. Bolton, it was reported, claimed that the murder of Bugs Moran had been plotted in “October or November” 1928 at a Couderay, Wisconsin resort owned by Fred Goetz.

Present at this meet were Goetz, Al Capone, Frank Nitti, Fred Burke, Gus Winkeler, Louis Campagna, Daniel Serritella, William Pacelli, and Bolton himself.

The men stayed two or three weeks, hunting and fishing when they were not planning the murder of their enemies.

Byron Bolton claimed he and Jimmy Moran were charged with watching the S.M.C. Cartage garage and phoning the signal to the killers at the Circus Café when Bugs Moran arrived at the meeting.

Police had indeed found a letter addressed to Bolton in the lookout nest (and possibly a vial of prescription medicine). Bolton guessed that the actual killers had been Burke, Winkeler, Goetz, Bob Carey, Raymond “Crane Neck” Nugent,[10] and Claude Maddox (four shooters and two getaway drivers).

Bolton gave an account of the massacre different from the one generally told by historians. He claimed that he saw only “plainclothes” men exit the Cadillac and go into the garage.

This indicates that a second car was used by the killers. One witness, George Brichet, claimed to have seen at least two uniformed men exiting a car in the alley and entering the garage through its rear doors.

A Peerless sedan had been found near a Maywood house owned by Claude Maddox in the days after the massacre, and in one of the pockets was an address book belonging to victim Albert Weinshank.

Bolton further indicated he had mistaken one of Moran’s men to be Moran, after which he telephoned the signal to the Circus Café. When the killers (who had expected to kill Moran and maybe two or three of his men) were unexpectedly confronted with seven men, they simply decided to kill them all and get out fast.

Bolton claimed that Capone was furious with him for his mistake (and the resulting police pressure) and threatened to kill him, only to be dissuaded by Fred Goetz.[citation needed]

His claims were corroborated by Gus Winkeler’s widow, Georgette, in both an official FBI statement and her memoirs, which were published in a four-part series in a true detective magazine during the winter of 1935–36.

Georgette Winkeler revealed that her husband and his friends had formed a special crew used by Capone for high-risk jobs.

The mob boss was said to have trusted them implicitly and nicknamed them the “American Boys”. Byron Bolton’s statements were also backed up by William Drury, a maverick Chicago detective who had stayed on the massacre case long after everyone else had given up.

Bank robber Alvin Karpis later claimed to have heard secondhand from Ray Nugent about the massacre and that the “American Boys” were paid a collective salary of $2,000 a week plus bonuses.

Karpis also claimed that Capone himself had told him while they were in Alcatraz together that Goetz had been the actual planner of the massacre.[citation needed]

Despite Byron Bolton’s statements, no action was taken by the FBI. All the men he named, with the exceptions of Burke and Maddox, were all dead by 1935.

Bank robber Harvey Bailey would later complain in his 1973 autobiography that he and Fred Burke had been drinking beer in Calumet City at the time of the massacre, and the resulting heat forced them to abandon their bank robbing ventures.

Claude Maddox was questioned fruitlessly by Chicago Police, and there the matter lay. Crime historians are still divided on whether or not the “American Boys” committed the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.[citation needed]

Other suspects[edit]

Over the years, many mobsters, in and out of Chicago, would be named as part of the Valentine’s Day hit team.

Two prime suspects are Cosa Nostra hit men John Scalise and Albert Anselmi; both men were effective killers and are frequently mentioned as possibilities for two of the shooters. In the days after the massacre, Scalise was heard to brag, “I am the most powerful man in Chicago.”

He had recently been elevated to the position of vice-president in the Unione Siciliana by its president, Joseph Guinta. Nevertheless, Scalise, Anselmi, and Guinta would be found dead on a lonely road near Hammond, Indiana on May 8, 1929.

Gangland lore has it that Al Capone had discovered that the pair was planning to betray him. Legend states that at the climax of a dinner party thrown in their honor, Capone produced a baseball bat and beat the trio to death.[11]

Murder weapons[edit]

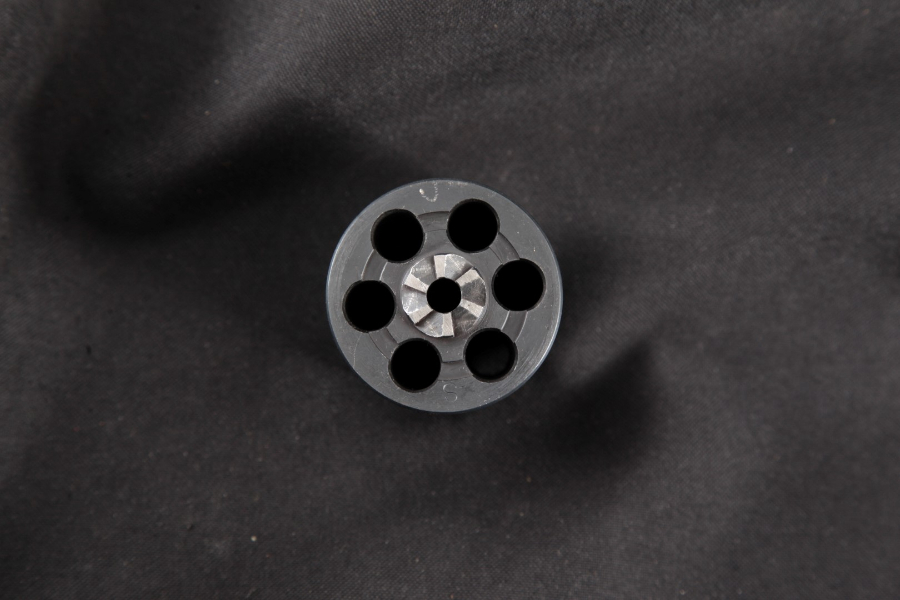

The two Thompson submachine guns (serial numbers 2347 and 7580) found in Fred Dane’s (an alias for Fred Burke) Michigan bungalow were tested and it was determined that both had been used in the massacre.

One of them had also been used in the murder of Brooklyn mob boss Frankie Yale, which confirmed the New York Police Department’s long-held theory that Burke, and by extension Al Capone, had been responsible for Yale’s death.

Gun No. 2347 had been originally purchased on November 12, 1924, by Les Farmer, a deputy sheriff in Marion, Illinois, which happened to be the seat of Williamson County.

Marion and the surrounding area were then overrun by the warring bootleg factions of the Shelton Brothers and Charlie Birger.

Deputy Farmer was documented as having ties with Egan’s Rats, based 100 miles (160 km) away in St. Louis. By the beginning of 1927 at the very latest, the weapon had wound up in Fred Burke’s possession. I

t is possible he had used this same gun in Detroit’s Milaflores Massacre on March 28, 1927.

Gun No. 7580 had been sold by Chicago sporting goods owner Peter von Frantzius to a Victor Thompson (also known as Frank V. Thompson) in the care of the Fox Hotel of Elgin, Illinois.

Some time after the purchase the machine gun wound up with James “Bozo” Shupe, a small-time hood from Chicago’s West Side who had ties to various members of Capone’s outfit.

Both submachine guns are still in the possession of the Berrien County Sheriff’s Department in St. Joseph, Michigan.

Legacy

Crime scene and bricks from the murder wall[edit]

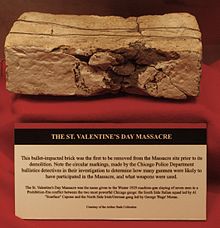

National Museum of Crime and Punishment – Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre brick (2868502113)

The garage, which stood at 2122 N. Clark Street, was demolished in 1967, and the site is now a parking lot for a nursing home.[12]

The bricks of the north wall, against which the massacre’s victims were lined up and shot, were purchased by a Canadian businessman.

For many years they were displayed in various crime-related novelty displays. Many of the original bricks were later sold individually, and the remainder are now owned by the Mob Museum in Las Vegas.[citation needed]

In popular culture[edit]

- “The Night Chicago Died,” a song by the British group Paper Lace, is about a shoot-out between the Chicago Police and gangsters tied to Al Capone. The song was inspired by the events of the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre.[13]

- Valentine’s Day, recorded by James Taylor in 1988 for the Never Die Young album, was inspired by the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre.

- Just For Money, recorded by Paul Hardcastle in 1985, features the massacre as well as the 1963 Great Train Robbery. It reached number 19 in the UK charts but did not chart in the US.

- In the movie Valentine’s Day, a schoolteacher asks her students what is special about Valentine’s Day, and one student mentions the massacre to her, much to her dismay.

- Rapper 50 Cent‘s 2005 album The Massacre was based on the event.

here is some more!

here is some more!