Category: War

As America geared up for war, the economy of building a wartime army was overwhelming. Tanks, aircraft, soldiers and weapons—all would consume huge resources, and manufacturers were challenged to reduce costs wherever they could. The arms industry was one area where the designers showed great creativity and were able to place function over form to accomplish their mission.

One of the more expensive (and iconic) weapons at the start of the war, the Thompson submachine gun, became a prime target for cost savings. In 1939, the M-1928 A1 Thompson cost the government more than $200 each—more than four times the monthly wages paid to a typical soldier. By 1942, design and production changes had brought the Army’s price down to around $75, and the final M1A1 variant hit a low price of $45 per copy by 1944.

Even so, in 1941 this was excessively expensive for a single weapon, so the War Department sought out a cheaper solution. That solution, the M-3 “Grease Gun,” came in at around $18.50 each, a savings of 90 percent.

As the war came closer to American shores, the U.S. Army Ordnance Board considered what was happening in Europe on the weapons front, including the German MP40 Schmeisser and the British Sten gun, and initiated a study to develop its own easy-to-make submachine gun. Early in 1942, the Army submitted a list of requirements for the new weapon, and Ordnance solicited a list of requirements from both the infantry and cavalry branches for a shoulder-fired weapon with full- or semi-automatic fire capability, in caliber .45 ACP.

Resting in a German house after a patrol, GIs keep their weapons, including two M-3 “Grease Gun” submachine guns, close at hand.

Resting in a German house after a patrol, GIs keep their weapons, including two M-3 “Grease Gun” submachine guns, close at hand.The list of requirements from each branch were then reviewed and modified at Aberdeen Proving Ground, and a tentative specification released to bidders. The initial T-15 specification of 1942 was for an all-metal weapon of stamped sheet-metal construction to fire the Army’s standard pistol cartridge (.45 ACP); to be designed for inexpensive production with a minimum of machining; and featuring both semi-automatic and fully automatic fire ability; a cyclic rate under 500 rounds per minute; and the ability to place 90 percent of all shots fired (from the standing position in full-automatic mode) on a 6×6-foot target at the combat range of 50 yards. The standard to which the new weapon’s performance was to be compared was the M-1928A1 Thompson, the “Tommy Gun.”

General Motor’s Inland Manufacturing Division in Dayton, Ohio, was just one of several companies that took on the challenge of developing this new weapon. Inland’s design team was already involved in the production of the M-1 carbine, so the chief engineer made this a personal project to plan for tooling and production.

The original War Department specs were simplified in late 1942 to remove the semi-automatic fire capability, and to propose an option to convert the weapon’s original caliber to the commonly available 9mmx19 pistol round that was used by both the Axis and Allied forces. The new specification for this dual caliber weapon was numbered T-20.

Five prototype models of the .45 T-20 and five 9mm conversion kits were built by GM’s Inland Manufacturing prototype shop and submitted for testing in November. At the Ordnance Department trials, the GM submission completed the endurance test with only two failures to feed in over 5,000 rounds fired. In the accuracy portion of the tests, the GM design scored an admirable 97 out of 100 possible hits on the 6 x 6-foot target. Then the real trials began.

Airborne Command, the Amphibious Warfare Board, the Infantry Board, and the Armored Forces Board were all encouraged to look at the best of the new designs. Each branch was told to independently test the T-20 prototype weapons, to see if this new, inexpensive weapon would meet their needs. All four review boards rated the basic GM design as “acceptable,” with similar suggestions and concerns.

All liked the short, handy size and reduced overall length, but all found fault with the GM-designed magazine and feed system, apparently due to the short, wide follower in the magazine that tended to tip or jam under hard use. The cocking handle was deemed too fragile, and the magazine could be difficult to fully load.

In spite of these faults, the T-20 was formally approved by the Ordnance Department for production in December 1942 as the “U.S. Submachine Gun, Caliber .45, M-3.”

The contract to build this new weapon was issued to the parent organization (GM), which proposed that the Guide Lamp plant in Anderson, Indiana, be the fabrication location, as they were familiar with metal stamping and welding operations and were not working at capacity (according to WPB inspectors). In 1942 this factory was producing blackout lights for Army trucks, M-2 HMG barrels, and parts for the P-39 Airacobra aircraft. With this contract, the Guide Lamp plant was at full capacity, with only 16 percent of the plant capacity dedicated to M-3 production.

When the exclusive contract was given, Guide Lamp produced a total of 606,694 of the M-3 variant sub-machine gun in 1943 and 1944. With no significant changes, the T-20/M-3 was produced as submitted. Even the balky 30-round magazine was put into production as submitted in the interest of expediency. Because of the prework done by the team at Inland, the first guns were able to be submitted for inspector approval within 45 days of the contract.

It was planned that the “Grease Gun” (so called because of its resemblance to the type of tool used by mechanics to lubricate a vehicle’s chassis and axles) or “Buck Rogers Gun” as it was nicknamed by the soldiers, would be produced in numbers sufficient to cancel orders for the more expensive Thompson submachine gun and to allow the Army to remove the Thompson from frontline service.

Due to production delays, design changes, and tooling problems, however, the M-3 never achieved its full potential during World War II, and purchases of the Thompson continued until February 1944. Considering the much longer service life, it is no surprise that the Allies put more than 1.5 million Thompsons into wartime service, outnumbering the M-3 by nearly three to one.

What did the Army get?

This new and inexpensive M-3 SMG used many automotive production-line processes to keep costs under control. Like the German MP40, the receiver was made of two deep sheet-metal stampings welded together to form the tube for the bolt. The small parts of the firing mechanism were steel stampings, castings, and pressings, with only three machined parts in the whole weapon. The barrel had to be rifled from formed steel tubing, the face of the bolt had to be precision ground, and the threads to retain the barrel were ground, but the balance of the gun was stamped, pressed, and welded.

The magazine was formed from sheet stock, and even the sights were stampings. (A creative note: The sights on the M3 were finished in the test-firing stage when a special drill bored the peep sight hole to align with where the gun put the bullets—not trying to move the sights to meet the point of impact after the fact.)

In the field, the weapon could be disassembled without tools for cleaning or conversion to 9mm. It was simple to work on, reliable, and cheap to build and feed. The firing rate was about half that of the Thompson, firing 300 to 400 rounds per minute, which allowed the individual soldier to stay “in action” longer.

Combined with the lighter weight of the weapon (eight pounds as compared to the Thompson’s 13+ pounds), the GI armed with an M-3 Grease Gun could carry more ammo and stay in the fight longer that one carrying the venerable M-1928 A1.

In combat, the GIs laughed at the ugly duckling. It lacked the fit and finish of the Tommy Gun, and had none of the “image” that came with the Thompson (which had been used by both gangsters and the FBI in the 1920s and 30s). But when the chips were down, the “Greaser” did its job. Dirt didn’t bother it (except that pesky magazine), it was short and handy, and threw enough of the man-stopping .45 ACP rounds that it could help decide a fire fight.

As one GI said, “I hated that gun when they gave it to me. It wasn’t as sharp looking as my Thompson, and looked like a leftover from the parts locker. But when I needed it, that gun never let me down. I didn’t clean it in combat—I just loaded it and drug it through the mud … and it kept shooting.”

In 1945, the Guide Lamp factory manufactured a simplified M-3 A1 sub-machine gun before production contracts were canceled with the end of the war. A total of 15,000+ were produced, but few saw combat in World War II. During the Korean conflict, the Ithaca Gun Company in Ithaca, New York, produced another 33,000 complete M-3 A1 guns, as well as manufactured thousands of parts for the repair and rebuilding of existing M-3 and M-3 A1 weapons.

The Army originally intended this weapon to be a disposable one—repair parts were not initially ordered or even in the supply system until the end of World War II. The plan, if it broke, was simple: drop it and pick up another. The majority of the failures in combat with this simple gun were related to the magazine, which remained an issue for its entire military career.

The 9mm conversion kit was not widely used, and it is estimated that approximately 1,000 kits were produced by the Rock Island Arsenal and by Buffalo Arms, as well as another 1,000 completed weapons produced by Guide Lamp. The kit consisted of a 9mm barrel, a revised bolt, and a magazine adapter that would permit the use of Commonwealth Stenmagazines. Another variant was produced upon request for OSS use that fitted a silencer to the original barrel. These weapons were built with sound suppressor components produced by High Standard on a Bell Labs design.

However, like many weapons of this era, the M-3 lasted longer in service than anyone thought it would. The Russian Army was provided with a large quantity as part of the U.S. Lend-Lease aid program, but the lack of ammunition left most of them in storage for most of their life. A copy (in 9mm) was produced for the Argentine Army through the 1970s, and was in service long after that time. Several units in the first Gulf War reported for duty with the M-3 or M-3 A1 “Greaser” as an individual-protection weapon for tank-recovery vehicle crews.

A DoD inventory in 1996 showed that more than 1,000 still remained in the depots. Unfortunately for the historical community, few of these have seen the light of day, and examples of the M-3 are seldom seen outside of museums.

The M-3 Grease Gun filled its intended role as an inexpensive, reliable weapon in a wartime economy. It used existing technologies and production methods in new ways to solve a problem and fill a need. While never as popular with the troops as its predecessor, it served the American GI and others around the world for 50 years, and serves as an example of what can be done when there is a need.

In April 1917, America’s armed forces were barely ready for a border skirmish with Mexican revolutionaries and bandits, much less the full-on slaughterhouse of the First World War. American small arms were excellent with the glaring exception of machine guns, of which the U.S. Army had very few. American military leaders had not yet learned the brutal lesson of the Great War for a new century: that automatic arms dominated the battlefield.

U.S. troops on the Mexican border with the Maxim Machine Gun, Caliber .30, Model of 1904. This was the first rifle-caliber heavy machine gun in U.S. Army service, however none of these guns were used by the AEF in France.

Just 18 months later, the situation had changed dramatically. At the end of World War I, American troops fielded the most complete and powerful set of infantry weapons the world had ever seen. By brave application of the force of arms coupled with our national design and manufacturing ingenuity, the United States transformed from a lesser Allied nation to an international superpower and world leader.

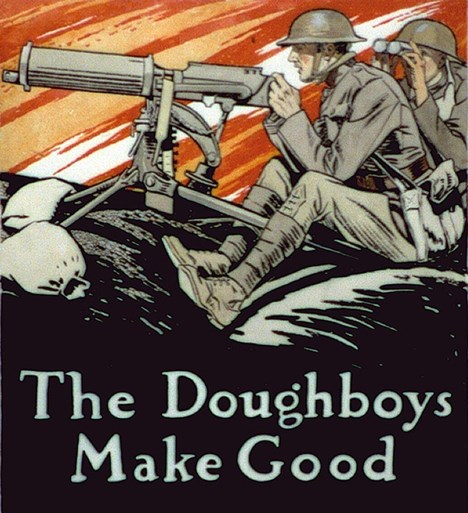

A wartime illustration depicting U.S. troops manning what looks like a cross between a British Vickers and an American Browning M1917 machine gun.

Here are a few of the machine guns in use by the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in France:

The French “Fusil Mitrailleur Modele 1915 CSRG”, or Automatic Rifle, Model 1915 (Chauchat). Regardless of its official title, American troops called the less-than-reliable Chauchat many names that cannot be repeated here. The most widely manufactured automatic arm of World War I, the Chauchat was a good early concept for an automatic rifle, but quite poorly produced. The AEF used the Chauchat in large numbers, chambered in its original French 8 mm Lebel. Subsequent attempts to chamber the Chauchat in the U.S. .30-‘06 cartridge ended in disaster, with the guns essentially unusable and quickly withdrawn.

U.S. troops training with the French designed and built “Automatic Rifle, Model 1915 (Chauchat).” Widely despised by American troops for its shoddy construction and subsequent unreliability, the “damned, jammed Chauchat” still served American troops throughout the battles of 1918. Three American Chauchat gunners earned the Medal of Honor.

The French Hotchkiss M1914 Machine Gun served as the AEF’s primary heavy machine gun until the Browning M1917 machine gun became available later in 1918. The 8 mm Hotchkiss proved to be accurate, reliable and adaptable. It was initially fed with 24-round metal strips, and later in 1917 an articulated metal belt was adopted. Hotchkiss machine guns were widely used in the burgeoning anti-aircraft role, and were also installed in many of the FT-17 tanks that were operated by the American Tank Corps.

The most common heavy machine gun in the hands of the AEF was the French 8 mm M1914 Hotchkiss. Sturdy, heavy, reliable and adaptable, about 7,000 of them served with American forces in France.

British Automatic Arms: Two American divisions were attached to the British in the Somme area, and thus spent some time using the .303 cal. Lewis Light Machine Gun, the Hotchkiss Portative light machine gun, and the Vickers Machine Gun in combat during 1918.

Marines training at Quantico with a Lewis Gun during 1916. While the Lewis was very popular with the USMC, the Marines’ Lewis guns were taken away and replaced with the less reliable French Chauchat machine rifle.

Browning M1917 .30 cal. Machine Gun: About 1,200 of John Browning’s heavy water-cooled machine guns saw service during the last three months of World War I. Very quickly, the M1917’s reliability, accuracy and rate of fire became legendary. The water-cooled M1917 served with U.S. forces in World War I, between the wars, throughout World War II, the Korean War, until phased out of U.S. service in the late 1950s.

Val Browning (son of the designer, John Moses Browning) test fires one of his father’s incredible designs, the Browning M1917 .30 cal. heavy machine gun. Fielded late in the war, the M1917 nonetheless established a reputation for reliability and accuracy.

These men of the 80th Infantry Division were armed with a Browning M1917 machine gun, which featured a “beer can” flash hider.

Browning Automatic Rifle: John Browning’s genius automatic rifle design only saw service very late in the war, beginning in about mid-September 1918. Regardless, the BAR quickly proved to be the finest light automatic of the war, impressing enemies and allies alike. First World War BAR gunners were initially provided with a special cup-like device, mounted on their cartridge belts, designed to hold the butt of the BAR stock firmly in place and enable the concept of “walking fire.” The walking fire concept proved to be completely impractical, but the BAR went on to be legendary, serving with U.S. forces even into the Vietnam War.

The outstanding Browning Automatic Rifle flanked by the French-built M1915 Chauchat in 8 mm Lebel (right) and the “American M1918 Chauchat” in .30-‘06 (left). Unfortunately for U.S. troops, the BAR did not reach frontline troops until the very end of the war, and the M1918 Chauchat in U.S. .30 cal. was almost completely non-functional.

Val Browning tries out a M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle in the “walking fire” style in France during 1918.

From The June 1944 Issue Of American Rifleman

In peacetime, when we talk of rifle shooting and rifle training and rifle competition, the general public thinks it’s just the hobby of a few—a small-time sport. Even in wartime, it takes time and battle experience to get down to the fundamentals. But now, just as in World War I, we’re learning that riflemen count, and that too much emphasis cannot be placed on their training. For battle riflemen aren’t made in a day, nor even in a few weeks on the range.

Here are some stories you haven’t seen in your daily papers—because these men are not heroes; they’re just good all-around riflemen:

On Mt. Castellone, one day in February, a two-hour Boche barrage heralded an attack by two German battalions on a ridge held by one platoon of one company of one battalion of the 36th Division. Two platoons were sent up to help meet that attack—less than a company, riflemen, with a few ’03 grenade launchers and a supply of grenades for close quarters—against two well-armed German battalions.

Platoon Sergeant H.C. Pruett, of Brownwood, Texas, was in charge of one of those two supporting platoons. The first platoon was already engaged when Pruett arrived. The Jerries had some four hundred yards to cover. Pruett threw his men into the fight as riflemen, in the prone or kneeling position according to each man’s locations. As riflemen, they started picking off Germans. The Boche were coming on in groups of three or four, running, ducking, hitting cover, rising to charge again. Pruett himself knocked down seven out of five different groups, getting one and sometimes two as each group made its short rush forward.

“The guys all around me were doing the same,” Pruett says. “We made ‘em pay for that yardage! But a few finally got up to within about fifty yards of us and we started heavin’ hand grenades.” That was a hot spot for Pruett and he was thankful the ‘03s would still work, for their rifle grenades were effective. “Must have had too much oil on the M1s,” he suggested. But he had some very definite opinions about marksmanship! “It pays off,” he said. “Every man ought to know his rifle, and how to shoot it. Hunting, back home, helped me. I’ve heard a lot of fellows say the same.”

Sergeant J.B. Johnson of Gustine, Texas, put the whole story of marksmanship in a few words when he said, “I don’t want a fellow around me that can’t shoot! He’s no help, and he’s just usin’ up ammunition—which, around these mountains, you can’t carry enough of, or get more!”

Yes, it pays. One hundred and thirty-two dead Germans were found in front of that ridge position. In the three defending platoons, only three men were hit with small-arms fire.

There is an old saying in the US Army which goes like this. Mess with the best and then die like the rest. It also amazes me that somebody that high up lives in such a fantasy world. I guess that when he was young that he was shielded from play ground rules. Its just a pity that so many folks on both sides have to pay with their blood & lives for such stupidity. Grumpy