Category: War

So true!

America’s enduring Model 1911 .45-cal., semi-automatic pistol remains a landmark sidearm more than a century later. Yet how it was introduced to service and typically carried by soldiers, sailors and marines before World War I remains lesser known.

Self-loading handguns became possible with the French invention of smokeless powder in 1884. Two blue-blooded Austrians, Karl Salvator and George von Dormus, patented their pistol in 1891, which held five rounds of proprietary 8 mm ammunition. It failed to find a market, but an improved version by another Austrian, Josef Laumann, entered production at Steyr the next year.

Thereafter, customer interest grew fairly quickly. In 1894, Hugo Borchardt’s C-93 in 7.65×25 mm attracted buyers with its eight-round detachable magazine, followed by Paul Mauser’s iconic “Broomhandle” in 1896, with ten rounds of 7.63×25 mm carried internally.

For the most part, the decade produced largely dead-end designs from Germany, Austria, Belgium and Spain, until Georg Luger arose. His 9 mm chambered P08 (for 1908) was first accepted by Switzerland in 1900, then by Germany along with many other nations.

In the United States, John M. Browning filed his first pistol patent in 1895, leading to the Belgian firm Fabrique Nationale’s hammerless .32-cal. Model 1899, followed by the enormously popular Model 1900 in .380 ACP. Retaining the detachable magazine but with grip and thumb safeties, the Model 1903 was produced in .32 and .380. Between them the Models 1900 and 1903 probably sold more than 850,000 units.

Placed in context, the .45 ACP emerged at the end of more than a decade of sidearm development. The M1892 was the first U.S. double-action revolver with a swing-out cylinder, chambered in the anemic .38 Long Colt. Adverse reports from the Philippine Insurrection, fought from 1899 to 1902, led to the M1909 in .45 Long Colt. A succession of variants emerged, with the stocks of the M1903 narrowed to provide an improved grip.

The stage for the M1911‘s development and adoption was set in 1907, when an Army board decided to replace its standard-issued revolver. Colt and Browning had collaborated on a nascent .41-cal. pistol round, but the Army’s Thompson-LaGarde ballistics tests of 1904 influenced development. Consequently, Browning modified the new cartridge as with a 200-grain, .45-cal. bullet, launched at 900 f.p.s.

The round appeared in the prototype Colt Model 1905, and after extensive testing by military and industry representatives, the final combination yielded the classic .45 ACP cartridge, with its 230-grain projectile launched at upwards of 850 f.p.s.

Army Ordnance concluded, “After mature deliberation, the Board finds that a bullet which will have the shock effect and stopping power at short ranges necessary for a military pistol or revolver should have a calibre not less than .45.”

Several aspirants entered pistols chambered for the new cartridge, and after elimination of other designs (including semi-auto revolvers), Colt’s and the Savage M1907 entries contended for the government contract. In the end, the final selection trial was not even close. The Colt ran flawlessly, while the Savage sustained dozens of stoppages.

As noted by American Rifleman’s predecessor, the April 1911 issue of Arms and the Man, declared, “the good old revolver became obsolete, and in its stead there was marked for the holsters of this Nation’s defenders the .45 Colt’s automatic; the latest, the most deadly, the finest and the best hand arm which had yet to be produced by man.”

Late in the final design process, the Army requested a thumb safety, which Browning added shortly before production began. The service requirement for a grip safety already was met, as Browning’s M1903 set the pattern for the military. Thus, the M1911 .45-cal. pistol evolved in a golden era of small arms design.

The Model of 1911 was adopted that March, with 21,000 delivered through December, including Navy and Marine Corps orders. Aside from the semi-automatic Mauser and Luger pistols, in the same period of time most nations were still introducing bolt-action service rifle designs.

Britain having adopted the Lee-Enfield rifle in 1895 and Germany’s Mauser designed Gewehr 98 came three years later. America had only adopted the classic Springfield M1903 rifle eight year prior.

Troops quickly noted the weight difference. The M1892 revolver weighed barely 2 lbs., while the Colt M1911 weighed nearly 2.5 lbs. with empty magazine, which may partly account for the decision to mate the pistol and holster to the sturdy 1910 pattern duty belt.

The Colt was carried in the M1912 holster, with a twin magazine pouch. Accessories were adaptable to the standard belt, which was frequently updated. Usually it was made of webbing or canvas duck, featuring rows of three vertical grommets to accept hooked hardware for holsters, canteens, and bayonets. Most of these pistols were produced with a lanyard loop in the butt, mainly for cavalry use.

In a 1913 article, Ensign C.E. Van Hook, an influential Navy instructor noted, “Eternal vigilance is the only price of safety.” Yet he commended the semi-automatic, partly because: “The trigger pull always remains the same, which is a decided advantage over the disconcerting double action of the .38-cal., and makes it a great deal more accurate for rapid firing.”

As issued, the Colt M1911’s trigger usually lets off at 6 to 7.5 lbs. Van Hook also noted “(the pistol) may be loaded with greater ease and rapidity. This takes into consideration the fact that under service conditions a number of extra clips, loaded and ready for instant use, would be carried in a specially designed belt.”

The M1911’s large frame caused problems for many users accustomed to the revolver’s smaller size. The Naval Institute Proceedings article observed, “One very simple way of overcoming most easily this short finger contingency lies in using the middle finger as the trigger finger. By using the middle finger, even without any previous practice, the shooter can get a better and freer purchase on the trigger.

Moreover, the middle finger is normally stronger than the index finger thus enabling the shooter to execute a smoother trigger squeeze. Let us assume that you are using the middle finger to “pull” the trigger. You will find it convenient to place the index finger either alongside the slide or on the receiver, depending on your own finger length.

However, the Army Ordnance manual of 1912 noted, “The trigger should be pulled with the forefinger. If the trigger is pulled with the second finger, the forefinger extending along the side of the receiver is apt to press against the projecting pin of the slide stop and cause a jam when the slide recoils. Additionally, some military teams allowed carving finger grooves in the 1911’s stocks for improved control, especially in rapid fire.

In 1926, the Army accepted modifications in form of the M1911A1, with an arched mainspring housing, a shorter trigger and frame indents behind the trigger. The annoying problem of hammer bite was largely eliminated with a shorter hammer spur and longer grip safety. However, many shooters preferred the original flat mainspring housing for greater purchase on the grip, and sometimes could retro-fit the original housing.

The Ordnance Departed listed muzzle velocity of 230-grain bullet at 802 f.p.s., penetrating 6″ of pine at 25 yards. Remarkably, trajectory was charted to 250 yards. The maximum ordinate was 4.29 feet (51.5″) at 126 yards. “The trajectory is very flat up to 75 yards, at which range the pistol is accurate.” (As a side note: General Joe Foss’ Air Force Reserve M1911A1, manufactured in 1944, grouped with 2″ extreme spread at 20 yards, but 8″ high.)

Reporting on range tests the manual said, “This pistol has been fired 21 times in 12 seconds, beginning with the pistol empty and loaded magazines on a table. Firing at 25 yards at a target 6 feet by 2 feet under the same conditions, 21 shots were fired in 28 seconds, making 21 hits with a mean radius of 5.85″.”

(Hatcher’s Notebook, page 421, described mean radius as the average distance of all shots from the center of a group; mean radius usually measured one-third of a group’s diameter.)

When action seemed imminent, the Army’s 1912 Description of the Automatic Pistol suggested topping off to eight rounds. The method seems peculiar today: with the magazine removed, lock the slide open and insert a cartridge in the chamber.

Trip the slide release, thus seating the round. Then a full-up seven-round magazine was inserted. It’s unknown how often loose rounds were available in the field. A far more likely technique was chambering the first round off one magazine and reloading with a full mag to bring the total to eight.

Addressing safety features: “The automatic grip safety at all times locks the trigger unless the handle is grimly grasped and the grip safety pressed in. The pistol is in addition provided with a safety lock by which the closed slide and the cocked hammer can be at will positively locked into position.” Decades later, speaking of the grip and thumb safeties, former Marine Lieutenant Colonel Jeff Cooper insisted, “If the 1911 were any safer it would be almost useless as a weapon.”

Decades of gun lore hold that the services originally carried the M1911 “cocked and locked,” or in today’s parlance, condition one. Presumably the policy changed after some negligent discharges. Allegedly, Lt. George Patton fancied himself a gunsmith and “improved” his automatic by filing the sear with exciting consequences, hence his devotion to revolvers. However, documentation indicates otherwise.

Contemporary sources heavily indicate that cocked and locked was only advocated facing imminent threat. The Ordnance manual noted that with a round chambered, “The slide and hammer being thus positively locked, the pistol may be carried safely at full cock, and it is only necessary to press down the safety lock (which is located within easy reach of the thumb) when raising the pistol to the firing position.”

However, Ordnance also advised, “Do not carry the pistol in the holster with the hammer cocked and safety lock on, except in an emergency. If the pistol is so carried in the holster, cocked and safety lock on, the butt of the pistol should be rotated away from the body when withdrawing the pistol from the holster in order to avoid displacing the safety lock.”

The problem, of course, is that it’s impossible to schedule an emergency. It was especially true in combat zones where enemy infiltrators or trench raiders might appear suddenly, at close range, often in darkness. Other concerns involved guard duty at a base entrance or building where emergencies seldom arose but the potential still existed.

The cavalry’s 1940 pistol field manual addressed modes of carry (page 19): “In campaign, when early use of the pistol is not foreseen, it should be carried with a fully loaded magazine in the socket, chamber empty, hammer down. When early use of the pistol is probable, it should be carried loaded and locked in the holster or hand. In campaign, extra magazines should be carried fully loaded.”

More than a century before the bane of today’s gun writers, the U.S. Government initiated the semantic heresy of referring to a pistol as a “revolver” and a magazine as a “clip.” An interwar Navy instruction advised, “Take the revolver in your right hand and the clip in your left. Show him how to insert the clip, trip the slide, inject the first round into the chamber, etc.”

The director of cavalry stipulated that mounted pistol exercises “will be carried on during the entire year.” Furthermore, drill would involve simulated firing at different objects at all gaits from walk to gallop.

Most targets were positioned at five to seven yards so troopers were required to engage right and left front; right and left flank; and right rear, the left hand of course holding the reins.

Anyone who has watched a SASS mounted event knows the common cavalry technique: leaning toward a front-aspect target while half rising in the stirrups, thrusting the pistol forward in the most direct line, wrist rigid, and forcing the right elbow to the left in vertical plane with wrist and shoulder. Trigger control was to be coordinated with start of the thrust, “He selects his target, fixes his eyes upon it with concentrated effort, catches sight of the target over his barrel, and squeezes his trigger with steadiness and precision.”

Live-fire drills showed the importance of follow through. Most misses were attributed to troopers’ failure to keep eyes on the target until after the shot was fired.

Concentration was paramount. Perhaps understandably in the midst of a cavalry charge, riders tended to look for the next target an instant before the round went. At all times troopers were strongly advised to keep the muzzle well ahead of the horse’s face for obvious reasons.

The manual devoted two pages to training horses not only around gunfire, but getting them accustomed to unusual sizes, shapes, and colors.

Long experience showed the wisdom of gradual exposure to unfamiliar objects and conditions, most often in groups rather than individually. Blanks and live fire were introduced as the mounts grew in confidence. Dismounted cavalry courses were fired at 15 to 50 yards, frequently walking toward pop-up targets. Various dates have been cited for the M1911’s combat debut, as early as 1913, but the most likely seems to be Marine Corps use in Haiti from 1915 onward.

In whole or in part, at least thirteen Army men earned the Medal of Honor with M1911s in World War I. Two Marines used Browning products twelve months after the armistice as Lt. Herman H. Hanneken and Cpl. William R. Button wielded both the M1911 and BAR, respectively, in their Medal action against Haitian rebels.

Since then, the M1911 has appeared in well over 120 theatrical movies through 2021, plus hundreds of television movies and episodes. That compilation excludes Commanders, Series 70/80s, other manufacturers, blank-firing copies, and portrayals in cartoons and video games.

In the 1969 film The Wild Bunch, a German advisor to the Mexican general notes that the Americans carry handguns “that may not be acquired legally.” In fact, the Colt Commercial “Government” models were marketed in 1912, with an initial run of 1,899 pistols.

The civilian market has only expanded in more than a century. Some 110 years later, the M1911 repeatedly finishes atop reader polls as “the most iconic American handgun.” Last year, Shooting Illustrated placed the M1911 ahead of the CZ 75 and Beretta 92, and even the classic 1873 Single Action Army. The fanfare of the M1911 shows no sign of abating.

The darkest day in the history of the Swiss Guard

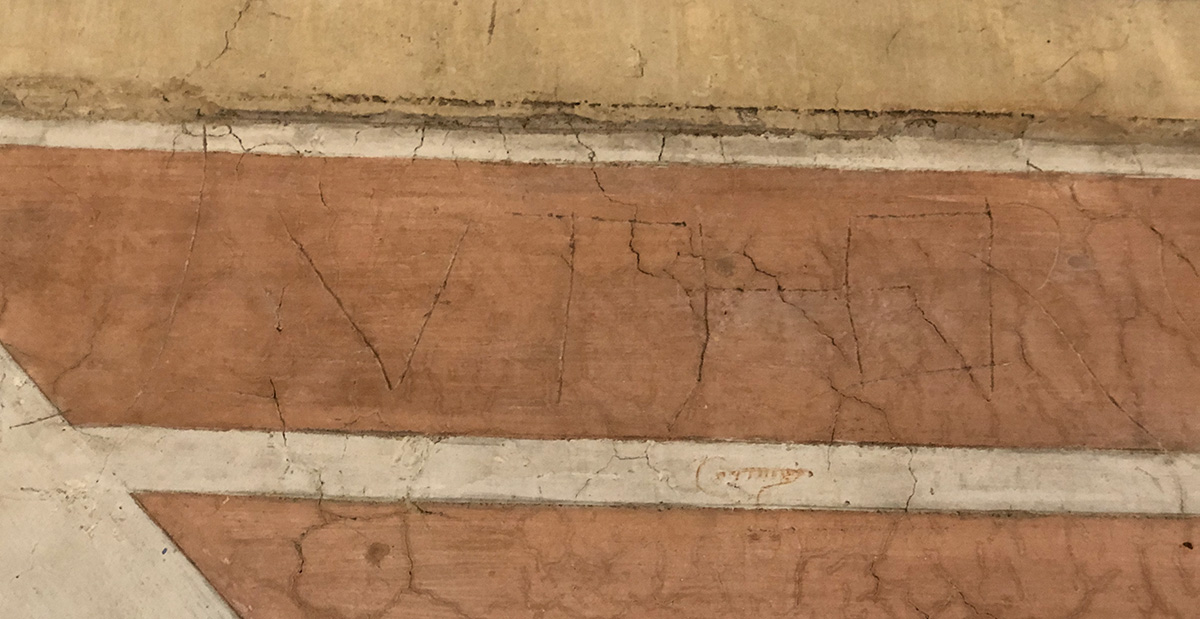

The Sack of Rome, or ‘Sacco di Roma’, by the leaderless troops of Charles V on 6 May 1527 ended in a bloodbath that also cost the lives of 147 Swiss guards. Traces of that dark day are still being discovered.

Henry Mucci and the Rangers – from The American Exprience

Mucci was so charismatic you couldn’t believe it… If you ever had to go to war, that’s the kind of man you wanted to go with.” — Alvie Robbins, PFC.

We all would have died for him, he was the very best.” — Vance Shera, Sergeant.

We knew he was selling us the blue sky, but we would have followed him anywhere.” — Robert Prince,<;C Company Captain

Extraordinary Fighters

General Walter Krueger and his top G-2 man, Horton White, were the ones to choose Mucci. As Krueger and White considered the raid, they knew they would need an elite fighting force. Hampton Sides, author of Ghost Soldiers, writes: “[They] would need a group of men trained in stealth techniques and the tactics of lightning assault.

The expeditioners must be in exceptional physical condition, as they would have to walk some 30 miles on foot in each direction, marching around the clock. They would have to be versatile, self-reliant, and extremely proficient with light arms, as the odds were better than good that they would encounter major enemy resistance along the trek.”

Intensive Training

Mucci had just such an outfit. In fact he had trained them: the 6th Ranger Battalion. Mucci was a man of vision. It was he who took the unit of Army mule skinners and turned them into the elite jungle fighting force known as the Army Rangers. For one year, in the mountains of New Guinea, Mucci trained his team, one of the first American special operations fighting forces.

Mule Skinners Become Rangers

The men Mucci had started with were for the most part boys from the farms and ranches of middle America — big, strong men. Known as “mule skinners,” they had been recruited to train in the mountains of New Guinea with heavy artillery carried on the backs of pack animals. By 1944, the Army considered the mule skinners obsolete, and General Krueger was looking to train a new special unit. Mucci was his man.

Testing Physical Limits

Ranger training under Mucci bordered on inhuman. A boxer, judo-expert, athlete, and former West Pointer, Mucci believed in training his men to the absolute limits of their physical capacities. He personally taught them all aspects of fighting: hand to hand combat, knifing, bayoneting and marksmanship. He led them on torturous exercises across the tropical New Guinea jungles, through treacherous rivers, and up mountainsides in the ferocious heat. Jungle combat, night combat, amphibious combat; Mucci taught and reveled in it all.

John Richardson, 6th Army Ranger, recalled: “I thought he was going to kill us. He called us rats, he called us everything but a child of God. And he told us, “I’m going to make you so d—– mean, you will kill your own grandmother…. I wondered why he was putting us through so much, but before it was over, there was no question about it, I knew why. And once he got us trained and picked out, he loved us to death. And there wasn’t anything too good for us…. He knew what he was doing when he was training us.”

Slave Driver — With a Purpose

Bob Anderson, 6th Army Ranger remembered, “He worked us so hard that sometimes I’d think I hate that man and I’d double-time back to my camp and say, ‘You can’t kill me, I can do more. You can’t give me enough, I can do more than you can give me.’ So he had us in shape and once he got us trained he was the nicest man you ever saw. But he knew how to train men.” No doubt, Mucci got his men in peak physical condition. They were ready for the raid. They were ready for anything.

Superb Leader

Sometimes the fit is perfect. Mucci was the right man to train and lead the Rangers. He had all the qualities of a superb military leader: he knew men, he had vision, and he was decisive. Robert Prince said, “He made a Ranger battalion out of a bunch of mule skinners, and he inspired us and trained us — and any success we had belongs to Colonel Mucci.”

Honors

The rest is history. Mucci’s actions and decisions on the raid were flawless. General Douglas MacArthur awarded Mucci the Distinguished Service Cross and said that the raid was ” magnificent and reflected extraordinary credit to all concerned.” The military promoted Mucci to full colonel.

National Hero

Upon his return home, Mucci was treated as a national hero in his home town of Bridgeport, Connecticut. He unsuccessfully ran for Congress and later became an oil representative for a Canadian firm in Bangkok. An athlete till the end, he died at 86 in Florida from injuries related to swimming in rough surf.