America’s interaction with Russia is quite the hot topic these days. Many Americans wonder, are the Russians friends or are they foes? In that light, little has changed from a century ago. In the summer of 1918, President Wilson committed American troops to Russia, and the country wasn’t sure what to make of it then either.

U.S. and allied troops on the march in Siberia.

The more time I spent researching the actions of the American Expeditionary Force Siberia, the more confusing their story became. The details, like names and places and dates, are relatively easy to come by. The big questions, like “why,” are much more difficult to answer. Apparently those questions were just as difficult to answer in 1918-1920.

The longer the intervention went on, the less that Uncle Sam’s frozen doughboys understood their mission. With the success of their deployment so poorly defined and their enemies growing in number by the hour, our troops were brought home. American intervention in Russia was quickly forgotten, and has rarely been discussed ever since.

When you think about it, the whole idea is rather shocking, then or now. American combat troops were stationed in tumultuous Russia, at that time a nation in the throes of a bloody civil war. While ostensibly protecting “Allied interests” in Siberia, one of the most inhospitable regions on the planet, U.S. troops traded shots with Bolshevik forces and occasionally with renegade Cossacks, all while trying to keep the peace among bitterly divided Russians and holding together a strange multi-national coalition of uncertain Allies. Small wonder that your high school history teacher never mentioned this in class. No worries, there will be no quiz at the end of this article either.

America Joins the Allies

As World War I wore on, Germany dreaded the prospect of America’s muscle bolstering the strength of the Allied nations. In April 1917, their fears were realized and the United States declared war on Germany. But America’s military would not be ready to make a difference on the battlefield for many months. In the meantime, Germany looked to break the stalemate in France before the arrival of American troops could tip the scales to the Allied side.

On Germany’s eastern front, the collapse of Czar Nicholas II’s Russian autocracy in October 1917 gave the Kaiser the break he had been looking for. The Russian front had kept 40 German divisions occupied in the east. The signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918 meant that the Russians were completely out of the war, allowing the Germans to fully concentrate on the western front. The German Army immediately launched a major offensive to bring their newfound divisions into action. England and France, dangerously short on men and resources, appealed to President Wilson to intervene in Russia to re-open the Easter Front and help relieve the growing pressure in Western Europe.

Browning M1917 MG position: U.S. troops pose with men of the Czechoslovakian Legion. It appears that the Czechs are armed with Japanese Arisaka rifles.

Allied intervention in Russia began with the best intentions, but with very little understanding of what was really going on inside that giant nation. The initial focus remained on defeating the Central Powers and ending World War I, thus the idea of reestablishing the eastern front and maintaining pressure on Germany and their Austro-Hungarian partners from both ends of Europe. There was also a significant amount of valuable military supplies kept in both Western Russia (Archangel) and in Far Eastern Russia (Vladivostok). Allied troops were deployed to secure them, and also to assist the Czechoslovak Legion, a large and effective group of troops that had been fighting alongside Russian forces for some time.

The Czechoslovak Legion had declared neutrality towards the communist Bolshevik forces, and thus had been granted safe passage home, albeit through Siberia. The 50,000-strong Czechoslovak Legion was taking the long way home, and they ultimately needed to be rescued from a country in the midst of a growing civil war.

Deployed to Russia

Lieutenant Colonel Nichols of the U.S. 31st Infantry Regiment, outside of Vladivostok.

In July 1918, President Wilson, despite the exhortations of his war advisors, agreed to send 5,000 U.S. Army troops, known as the “American North Russia Expeditionary Force” (also called the Polar Bear Expedition) to Archangel. Another group, numbering about 8,000, called the “American Expeditionary Force, Siberia”, would be sent to Vladivostok. American troops were soon on their way and going to war in Russia.

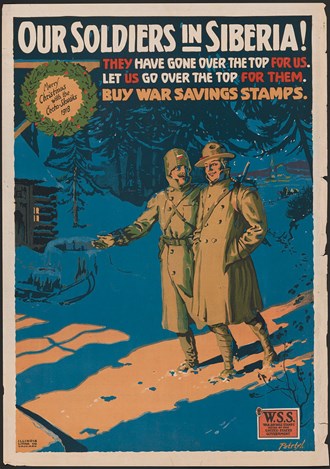

Christmas greetings from Siberia: U.S. War Stamps poster highlighting the American troop deployment to Russia in 1918.

U.S. troops would not be alone in Siberia. Allied intervention in far eastern Russia also included groups of a few thousand British, Canadian, French, Italian and Chinese troops. Then came the Japanese. Originally expected to deploy about 7,000 troops, the Japanese ultimately sent a force of 70,000 men to Siberia.

Japan’s strange commitment of such a large force for a “rescue mission” heightened mistrust of their ultimate intentions in the region. Major General William Sidney Graves, the U.S. commander in Siberia, kept a close eye on his Japanese allies. Even so, by November 1918 the Japanese had occupied the ports and major towns throughout the Russian Maritime Provinces and they also occupied all of Siberia east of the city of Chita. They would keep much of this territory for several years after the other Allied troops had been withdrawn.

Bolsheviks: Russian communists fighting against the White government of Siberia led by Admiral Kolchak.

As for the Russians in Siberia, there were an increasing number of Reds, the communist Bolsheviks. During the first few months of the intervention there were an equal number of White forces—anti-communist troops that were greatly strengthened by the combat-hardened Czech Legion. Unfortunately, the White Russians were frequently at odds with each other.

The recognized White Russian government was led by Admiral Alexander Kolchak, and the anti-communist Cossacks were led by Grigory Semyonov and Ivan Kalmykov. Both groups were generally brutal to anyone in their path, and the Cossacks were notably unpredictable in any situation. If politics makes strange bedfellows, then Siberia was an orgy of ideological confusion.

Hardened veterans of the Czech Legion armed with the Mosin-Nagant M1891 rifle. The surviving members of the Legion finally made it home in the summer of 1920.

President Wilson defined the objectives of U.S. policy in the Russian intervention within a short, and not particularly detailed, memo that Major General Graves adhered to for the most part. Wilson’s basic points were:

- The primary objective is to win the war against Germany.

- The U.S. will not interfere in Russian internal affairs.

- Military action is admissible to help the Czechoslovakian Legion.

- American troops will be employed to guard military stores.

- The United States will not limit the actions or policies of its allies.

- American forces will be withdrawn if and when necessary.

American Troops in Siberia

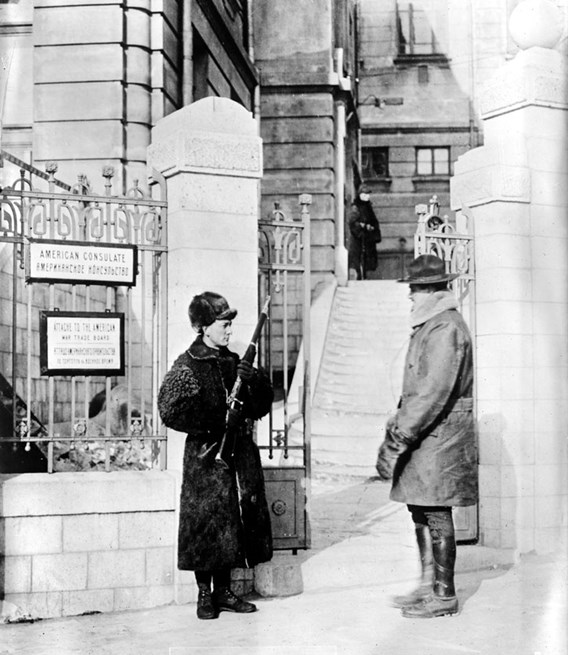

On guard at the U.S. consulate in Vladivostok. Note the locally sourced cold-weather gear.

As American troops began to arrive in Siberia in September 1918, it was already turning cold, and it was quickly apparent that the expedition was not properly equipped for the harsh climate. Antique cold-weather gear, even relics of the Indian Wars of the late 19th century, was issued to some of the men. Other warm clothing had to be procured locally until proper supplies from home could be obtained.

One of the many parades in Vladivostok. American troops march while Japanese troops stand in review.

Duty in Siberia was as tedious as it was cold. Pointless parades on the streets of Vladivostok, along with continuous drilling, became the order of the day. The unyielding cold wore the men down. Unrelenting boredom eroded morale. Uncertain of their allies, and restricted from fully engaging any enemies they encountered, the expedition foundered—but still they stayed.

Confusion and dissention about the intervention mission distracted U.S. officials. General Graves commented: “Representatives of the War Department and the State Department were carrying out entirely different policies at the same time in the same place. There can be no difference of opinion as to the accuracy of this statement, and the results were bitter criticism of all United States agents.”

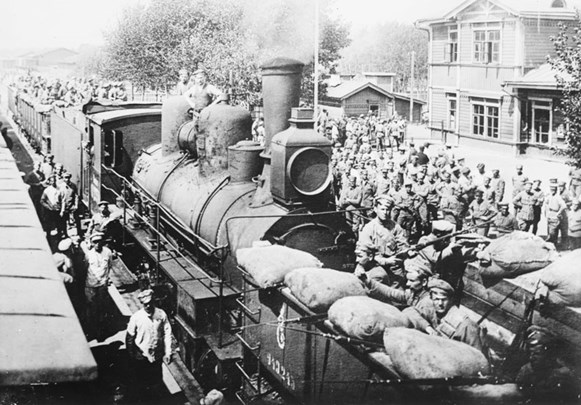

Working on the railroad: Guarding the railways was of critical importance in Siberia.

General Graves stayed consistent in his interpretation and execution of President Wilson’s intervention policy memo. This meant that American troops in Siberia guarded the stocks of war supplies around Vladivostok and also protected the Trans-Siberian Railroad. As compared with their counterparts in Northern Russia, the troops in Siberia rarely fought with the Bolsheviks. However, when American troops did engage the communists in Siberia, the Reds paid a stiff price.

Czech Legion train, veteran of their Trans-Siberian rail trek. The graphic roughly translates to: “Better to fight and die than to live as a slave.”

So too did the Cossacks, when American troops’ sense of justice and human decency was stretched to the breaking point. Cossack groups refused to answer to any authority, and they ranged throughout Siberia, occasionally fighting the Bolsheviks, but most frequently they were engaged in raping and pillaging the locals. As time went on, the Cossacks played both sides, alternately fighting under Red banners or White, whichever served their purposes at the moment.

Czech Legion train: Armed and armored trains were a dominant force in Siberia.

During the early morning of January 10, 1920, the Bolshevik armored train “Destroyer,” under the command of Cossack General Ataman Semionoff, attacked a train station guarded by American troops. Fighting in temperatures that had fallen to 30 degrees below zero, the American platoon resisted fiercely, holding off forces superior in number and firepower. Their subsequent counterattack disabled the armored train and captured its crew. Two Americans died and one was wounded in this final combat action for American troops in the World War I era.

Cold weather duty: U.S. soldier with a M1903 rifle, standing guard in Vladivostok during late 1918.

All told, 48 American soldiers lost their lives during the intervention in Siberia. Many more were casualties of severe frostbite and a collection of diseases, ranging from virulent flu to a form of plague. Many men suffered from venereal disease. Keeping the soldiers warm, as well as entertained, apparently came at some great cost in Siberia.

The End of the Intervention

During the summer of 1919, Admiral Kolchak was captured by the Red Army and executed. With his death, the White Russian regime in Siberia disintegrated. During the next 10 months, most Allied forces began to withdraw. With the war in Western Europe over, and a new homeland to return to, the Czechoslovak Legion was finally evacuated. By June of 1920, all of the Allied forces (with the exception of the Japanese) had left Siberia. Japanese troops would stay on until October 1922, when diplomatic pressure from England and the United States, as well as opposition from their own people, forced them to call their troops home.

Defrosted Weapons Report: American Arms in Russia

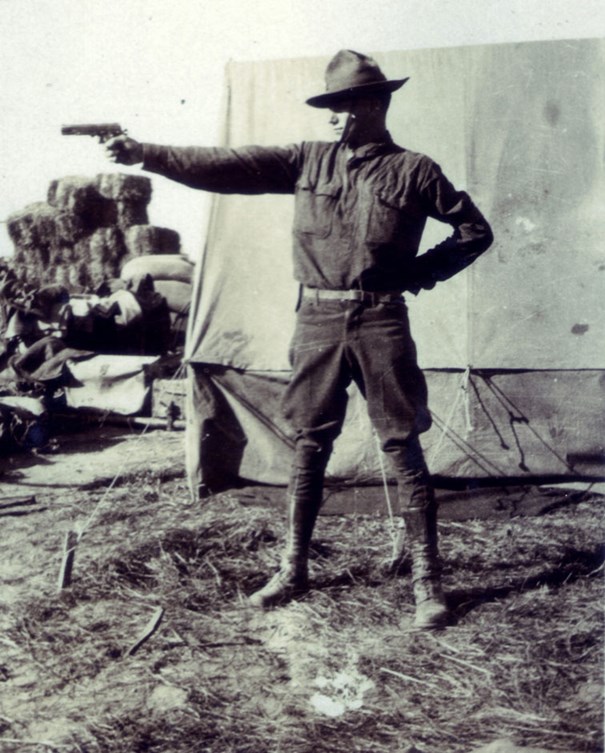

American troops deployed to Siberia with a full complement of modern small arms. The backbone of U.S. forces was the excellent M1903 Springfield rifle. Supporting arms included the new M1917 Browning .30-cal. machine gun and the Browning Automatic Rifle. Troops carried the .45-cal. M1911 pistol as their sidearm.

Springfield rifles in Russia: U.S. infantry in Siberia in the spring of 1919.

There was no shortage of weapons or ammunition. Records indicate that more 10 million rounds of .30-cal. ammunition were sent to Siberia, along with 350,000 rounds of .45-cal. ammo. There was plenty of ammunition to feed the 16 Browning M1917 machine guns, 46 M1915 Vickers machine guns, 370 Browning Automatic Rifles, more than 1,000 M911 pistols and approximately 7,000 M1903 rifles that armed the troops in Siberia.

The M1915 (.30 cal.) Colt-Vickers machine gun. The Siberian intervention force had nearly 50 of these highly effective MGs in their arsenal.

The 27th and 31st Infantry Regiments arrived in Vladivostok equipped with the Model 1909 Benet-Mercie light machine guns, but these were quickly replaced by BARs and the Benet-Mercie MGs were returned to the Philippines.

The machine gun cart for the M1917 Browning machine gun proved popular among the troops stationed in Siberia.

The M1903 rifles and BARs received high marks from the infantry as well as the ordnance specialists. The Vickers and Browning heavy machine guns operated flawlessly, and their supporting “machine gun carts” (normally towed by a mule) were highly valued. A metal towing pole and rope were provided so that the MG carts could be towed by hand if needed.

The “Amerikanski Colt,” The M1911 pistol developed an intimidating reputation among the Russians on both sides in Siberia.

Apparently, the M1911 pistol gained quite a reputation during its service in Siberia. There are claims that the “Amerikanski Colt” could disperse unruly crowds with just the mention of its name. Those big .45 slugs could make equally big holes in “Reds” or “Whites” alike and provide a fitting testament for America’s attempt to bring peace to Russia through superior firepower.

Additional Reading:

Cold Front: American Troops in Russia 1918-1919