Category: War

Winchester M1897 Trench Gun

HMS Ark Royal early in WWII

HMS Ark Royal early in WWII

The Second World War was the Royal Navy’s finest hour, so says the acclaimed naval historian, Paul Kennedy.

There are many remarkable aspects to Victory at Sea that might be the subject of an individual blog, but one I would like to call attention to is the way the book, and perhaps especially Ian Marshall’s illustrations, confirm how much the 1939-1945 war at sea was the Royal Navy’s War.

It was there at the very start, pushing out patrols and hunting-groups in search of the German surface raiders; and it was there at the every end, with British warships [HMS Duke of York] among the Allied fleets in Tokyo Bay in 1945, and another bidding godspeed to Pres Truman in Plymouth harbor after the Potsdam settlement is over.

By my count, a full 23 out of the 53 beautiful Ian Marshall paintings are of ships and naval actions involving the Royal Navy, and they range from paintings of storm-tossed little escorts to magnificent ones of the HMS Ark Royal being slowly towed into Malta’s Grand Harbour. The very cover of this book shows, dramatically, the Bismarck under attack by the puny [if also very effective] Swordfish torpedo planes.

Chapter after chapter of this book is devoted to what was really the greatest, longest-lasting maritime struggle of all, the Battle of the Atlantic, not concluded until the serried ranks of Doenitz’s U-boats were tied up in Allied harbours. And from chapter 5 there begins another campaign story, that of the Battle of the Mediterranean, including the Taranto Raid and the many Malta convoys. A whole number of Ian Marshall’s paintings are of British warships at Malta, because that was one of his favourite places as a backdrop to his art.

And this was a Royal Navy which was willing to take incredible losses in the fight to keep control of the sea. Of course Churchill would have it no other way, but the service itself never flinched at the high costs of fighting – there is considerable detail throughout this book of the HUGE losses of merchant ships and escorts in the Atlantic and Arctic convoy campaigns, the stupendous cost in Royal Navy destroyers off Dunkirk and Crete, the terrifying Malta convoy experiences – just count how many cruisers and destroyers, not to mention the many original carriers, were lost against enemy action in this war.

And yet this was a navy that was still receiving newer and more effective warships from the hard-working British shipyards throughout the war: new KG-V-class battleships, the Illustrious-class carriers, town-class cruisers then many new light cruiser classes, fleet destroyers, frigates, sloops, corvettes.

If the lengthy conflict wore down the British economy, there was no sign of that until the very end – although it was clear by 1943 (this is one of the big points stressed in this book) that the US Navy was emerging as a far larger force than anything that had been seen in world history. And this is why, surely, the sub-title of this book Naval Power and the Transformation of the Global Order in World War II is most appropriate..”

Paul Kennedy is the author of Victory at Sea: Naval Power and the Transformation of the Global Order in World War II, published by Yale University Press.

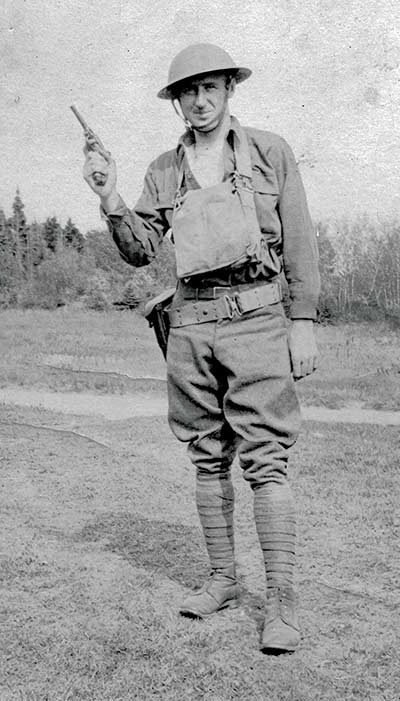

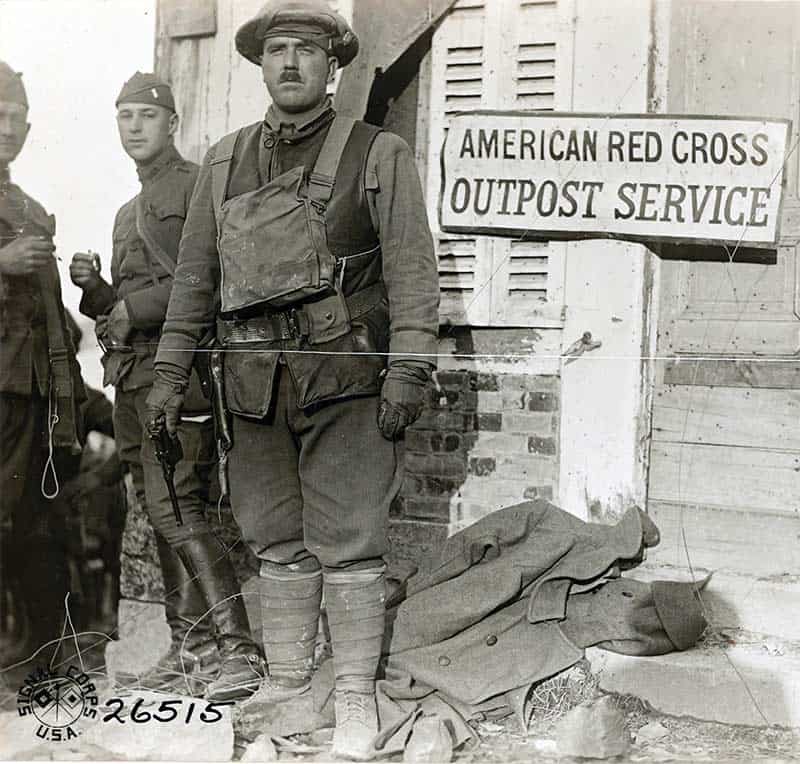

When American troops began to deploy to France in late 1917, they would soon realize the horrors of modern warfare. But they would also find one of the few pleasures for the combat soldier, and in WWI, that meant the beginning of a joyful harvest of German war trophy pistols.

WW I Trophy Hunting

By 1918, the German 9mm Pistole Parabellum, commonly known as the Luger pistol, became one of the most sought-after souvenirs of the Great War. The Luger and the Mauser C96 “Broom Handle” (chambered in 7.63x25mm) were not only prized trophies — the Doughboys found them quite useful and turned them against their former owners.

Even while there were plenty of U.S. .45 ACP pistols available (the M1911 auto pistol and the M1917 revolver), any red-blooded American boy will tell you two guns are better than one — particularly when your life depends on them. Even after the war was over, the American army of occupation in Germany continued its interest in war trophies, particularly the pistol variety.

The expression “The English fight for Honor, the French for Glory, but the Americans fight for Souvenirs!” is said to have originated in 1918. It is confirmed in multiple post-war assessments by German troops and civilians concerning American troops.

U.S. Intelligence officers conducted a series of interviews immediately after World War I. One letter from a German in Treves said: “The American discipline is excellent, but their thirst for souvenirs appears to be growing.” A shopkeeper from Bad Neuenahr quipped: “I alone have sold more Iron Crosses to American soldiers than the Kaiser ever awarded to his subjects.”

German pistols became scarce in the 1918–1919 era and unless you picked one up yourself (the hard way), their prices rose steeply. On the plus side, there were no gun laws in the U.S., so if a Doughboy could capture it, trade for it, or buy it, he could bring that pistol, rifle, or even machine gun home with him. After all, World War I was called “the war to end all wars” and nobody believed this world would be stupid enough to go to war again. But sadly, there would be another bigger and better chance for American troops to pick up German pistols on the battlefield just a quarter-century away.

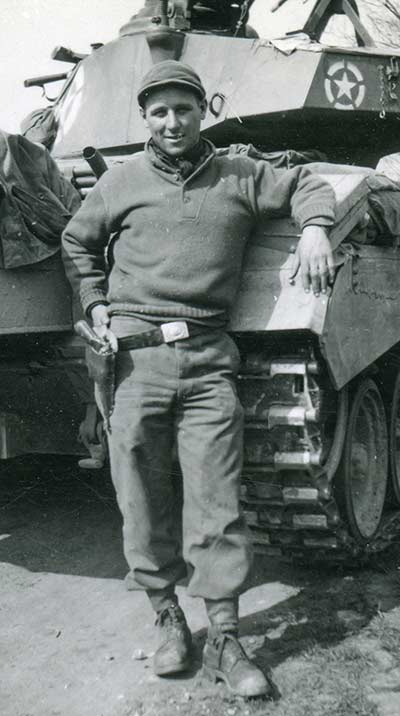

Act II: ETO War Trophies

When U.S. forces met German troops in combat in World War II, American interest in German pistols, particularly the Luger, was reinvigorated. The U.S. Military Intelligence publication German Infantry Weapons (May 1943) described the Luger in detail for troops in the field:

“The Luger Pistol: Since 1908, the Luger pistol has been an official German military sidearm. In Germany, Georg Luger of the DWM Arms Company developed this weapon, known officially as Pistole 08, from the American Borchart pistol invented in 1893. The Luger is a well-balanced, accurate pistol. It imparts a high muzzle velocity to a small-caliber bullet but develops only a relatively small amount of stopping power.

Unlike the comparatively slow U.S. 45-caliber bullet, the Luger small-caliber bullet does not often lodge itself in the target and thereby impart its shocking power to that which it hits. With its high speed and small caliber, it tends to pierce, inflicting a small, clean wound. When the Luger is kept clean, it functions well. However, the mechanism is rather exposed to dust and dirt.

“Ammunition: Rimless, straight-case ammunition is used. German ammunition boxes will read ‘Pistolenpatronen 08’ (pistol cartridges 08). These should be distinguished from ‘Exerzierpatronen 08’ (drill cartridges 08). The bullets in these cartridges have coated steel jackets and lead cores. The edge of the primer of the ball cartridge is painted black. British- and U.S.-made 9mm Parabellum ammunition will function well in this pistol; the German ammunition will, of course, give the best results.”

Don’t Touch That …

The Luger’s popularity among U.S. troops did not go unnoticed by the Germans. Several wartime cautionary tales emerged as the Luger was sometimes used as “bait” for a booby-trap, ready to catch an over-eager trophy hunter. Other claims were circulated that German troops executed Americans captured carrying German pistols, but this was never substantiated. The February 1945 edition of the U.S. Intelligence Bulletin contained this warning:

“Charges Concealed in Weapons. The Germans sometimes conceal a small charge in the mechanism of a rifle or Luger pistol that they plan to leave behind in a fairly obvious place, to attract the attention of Allied soldiers. The charge, which is sufficiently powerful to injure a man severely, is detonated if the trigger of the weapon is pressed.”

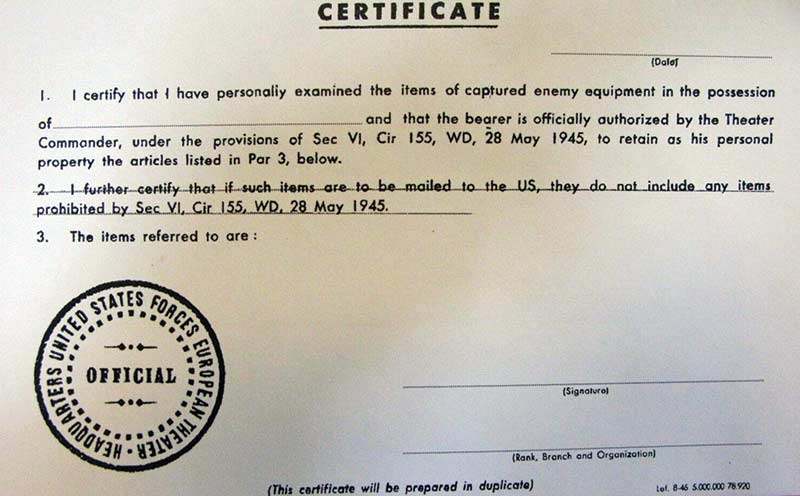

Bring-Backs & Send-Homes

Such was the mania among GI souvenir hunters to pick up German pistols (and any other German firearm) on the battlefield that the U.S. Army and the U.S. Customs Bureau went to great lengths to approve, then control, and then ultimately restrict American troops’ ability to bring or send the captured weapons home.

Beginning in 1944, a U.S. government certificate (often called “capture papers”) was provided to GIs that would allow them to send home or carry home a wide range of war trophies. Signed by their commanding officer, these rather vague certificates gave troops a near carte blanche to pass almost any captured firearm through U.S. customs, at least for a time.

Shortly after the war ended, a U.S. Army regulation effective May 28, 1945, limited War Trophy firearms to one per soldier and strictly enforced the prohibition of the importation of machine guns. It all looked good on paper anyway, but most GIs (and apparently their officers) ignored it. Your dad or grandpa put his captured pistol in his duffel bag and carried it home, or he packaged it up and mailed it to the states.

I’ve never seen any credible estimate on the number of German pistols brought home from the world wars. I’m not good at math, so I won’t guess at the total — other than to say, “a lot.” Even so, it is rare to find a WWII trophy pistol complete with its capture papers — the documentation doesn’t change much, but it is an interesting notch on a collector’s belt.

Technicalities

I did a little digging and found how Uncle Sam defined “war trophies” and the guidelines of how they could be possessed and brought to the United States as personal property.

“War Trophy: In order to improve the morale of the forces in the theatres of operations, the retention of war trophies by military personnel and merchant seamen and other civilians serving with the United States Army overseas is authorized under the conditions set forth in the following instructions. Retention by individuals of captured equipment as war trophies in accordance with the instructions contained herein is considered to be for the service of the United States and not in violation of the 79th Article of War.

“All effects and objects of personal use — except arms, horses, military equipment, and military papers — shall remain in the possession of prisoners of war, as well as metal helmets and gas masks.

“When military personnel returning to the United States bring in trophies not prohibited, each person must have a certificate in duplicate, signed by his superior officer, stating that the bearer is officially authorized by the theatre commander, under the provisions of this circular, to retain as his personal property the items listed on the certificate. The signed duplicate certificate will be retained by the Customs Bureau; the original will be retained by the bearer.

“Military personnel in theaters of operations may be permitted to mail like articles to the United States, except that mailing of firearms capable of being concealed on the person is prohibited. Parts of firearms mailed in circumvention of this prohibition are subject to confiscation by postal authorities. Parcels mailed overseas which contain captured materiel must also contain a certificate in duplicate, signed by the sender’s superior officer, that the sender is officially authorized by the theater commander to mail the articles listed on the certificate. The Customs Bureau will take up the signed duplicate certificate and leave the original inside the parcel.

“By order of the Secretary of War: G.C. Marshall Chief of Staff August 21, 1944.”