Category: War

Private First Class Ralph Kollberg, a combat veteran of the U.S. Army’s 77th Infantry Division, poses with his M1919A6 machine gun on Okinawa, May 14, 1945. Despite the gun’s 32-lb., 8-oz., weight, it was far more portable than the tripod-mounted M1919A4.

One of the most popular and effective U.S. small arms of World War II was the M1919A4 light machine gun. Despite the almost universal accolades heaped upon the M1919A4, the U.S. Army Ordnance Dept. continued to seek ways to increase the gun’s utility. While attempting to improve upon existing designs is not a bad thing in and of itself, sometimes the “Law of Unintended Consequences” comes into play.

A good example of this in the realm of World War II U.S. military arms was the Model 1918A2 Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). As a brief review, when the M1918 BAR was fielded late in World War I, it was an immediate sensation and was, hands-down, the best gun of its genre in the world at the time. The Ordnance Dept. couldn’t leave well enough alone, however, and after World War I, the BAR was subsequently fitted with all manner of attachments that were intended to improve it, including bipods, stock rests, folding buttplates, receiver magazine guides and carrying handles. The popular selective-fire feature allowing either full-automatic or semi-automatic operation was discarded on the M1918A2 version and was replaced with a full-automatic-only mechanism consisting of “slow” and “fast” cyclical rates of fire that few of the users liked, or employed, and which was prone to malfunction.

Most of these “improvements” offered few real advantages but seriously mitigated one of the major hallmarks of the original design—its comparatively light weight and handiness. This resulted in many of the users disregarding or stripping off as many of the extraneous features as possible, especially the bipod, in an attempt to put the gun back in the configuration originally designed by John Browning.

A similar scenario occurred during World War II with the M1919A4 machine gun. Since before World War II, the U.S. military had been seeking a gun that could fill the perceived gap between the BAR and the M1919A4. Several designs were evaluated in 1941 and early 1942, but none were deemed to be satisfactory. As the war progressed, there were increased requests for a machine gun of this type. Although the M1919A4 was widely used with notable effectiveness during the war, there were some negative points cited in a 1943 Marine Corps evaluation of the gun:

“Some weapons platoon leaders believe the gun (M1919A4) to be too slow in getting into action and the crew too vulnerable. It is suggested that a new mount for close in jungle fighting be designed, on the order of the bipod and butt-rest similar to the BAR M1918A2 with the addition of a carrying handle on the barrel jacket similar to the British Bren.”

The Ordnance Dept. wanted to develop a new type of gun with the attributes that were being sought and resisted the suggestions to simply field a modified M1919A4 instead. A World War II Ordnance Dept. report stated: “[It] is believed that no advantage would accrue in recommending a modification of the M1919A4 machine gun at this time, as such modifications would meet the approved military characteristics of the light machine gun in part only.”

The Infantry Board did not agree with the Ordnance Dept. assessment and was of the opinion that a modified M1919A4 might not be optimal, but it would fulfill the requirements until a more suitable type of firearm could be developed.

As documented in an Infantry Board report: “The Infantry Board favors a project by the Ordnance Department for the development of a light machine gun. However, based on past experience, the Board believes that the time consumed in the development, technical testing, production of pilot models, service testing, adoption as standard for issue, set up for manufacture and distribution to the services will be so great that under the best of conditions of accelerated procedure, it will be a distant date before the weapon can be placed in the hands of the troops. These modifications for the M1919A4, namely a lighter barrel, no muzzle plug, an 041 spring, a bipod and a shoulder rest … should present no great manufacturing difficulties, and after the items are manufactured, the modifications can be made in the field. If this is accomplished, the services would have a flexible and satisfactory light machine gun at an early date, certainly many months before a new type of light machine gun can be developed and distributed.

“While these modifications [of the M1919A4] do not constitute the ultimate in the development of a light machine gun, they do give a satisfactory gun in a minimum amount of time and manufacturing adjustment.

“The Infantry Board considers the modification of the M1919A4 Machine Gun a matter of major importance to the infantry … and recommends that action be taken to accomplish this modification … .”

This position was very much akin to the hoary old saying, “Perfect is the enemy of the good” or, to paraphrase Gen. George S. Patton, “A good plan now is better than a perfect plan later.” The Infantry Board prevailed, and the modified M1919A4 was recommended for adoption as the “M1919A6.” As stated in the book Machine Guns Of The United States: “The most recent modification of the Model 1919A4, for infantry use, is the Model 1919A6 which incorporates a pressed-metal shoulder stock, a carrying handle, and a bipod similar to that used with the Browning Automatic Rifle. This results in a light machine gun—classed as substitute standard—suitable for air-borne troops as well as for general use. Though the barrel of this gun weighs 2.5 pounds less than that of the 1919A4, the two are interchangeable. This model became substitute standard on April 10, 1943.”

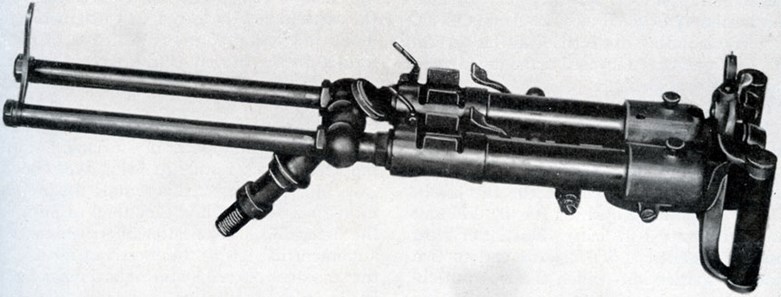

The M1919A6 machine gun was succinctly described by noted author and former Ordnance Dept. officer, the late Konrad F. Schreier, Jr.: “[T]he most unique gun in the M1919 series was the M1919A6. It featured a detachable shoulder stock, a folding bipod on the end of the barrel, a carrying handle, a different barrel bearing than the M1919A4 and a lighter barrel.

Its basic action was identical to the air-cooled M1919A4 machine gun. The gun weighed 32.5 pounds, which made it 12.5 pounds lighter than the M1919A4 mounted on the M2 tripod. A total of 43,479 M1919A6 light machine guns were produced during World War II by Saginaw. However, a number of M1919A4 machine guns were also converted into M1919A6 configuration. The M1919A6 machine guns were manufactured from very late 1943 through 1945. The M1919A6 machine gun could also be used with the M2 tripod if necessary.”

The Ordnance Dept. was not a big fan of the M1919A6, and basically felt that the gun was foisted upon it by the Infantry Board. Paradoxically, while the Infantry Board was successful in lobbying for acceptance of the modified M1919A4, as events transpired, the Board wasn’t overjoyed with the M1919A6 either.

As related by author Dolf Goldsmith: “[T]he Ordnance Department … was most unhappy about their inability to create and supply the infantry with what they had requested … . After the M1919A6 was accepted, testing began anew. Every conceivable facet of the gun was tested … throughout the spring and summer of 1944 … the infantry was … less than happy with the M1919A6, but there was simply nothing else available that could have been used instead. This grudging acceptance is well brought out in one of the test reports, which concluded:

“That the Production Model, Machine Gun, Caliber .30, M1919A6 is substantially equal to the pre-production model as tested and approved, and is satisfactory as an intermediate type.

“That the Machine Gun, Caliber .30, M1919A6, is not a satisfactory light machine gun for infantry use.

“The Infantry Board recommends:

a. “That no action be taken looking at any modification or change in the Machine Gun, Caliber .30, M1919A6.

b. “That development of a more suitable light machine gun for infantry use be pushed.”

It seemed the Infantry Board was talking out of both sides of its mouth. On the one hand, it was stated that the M1919A6 “ … is satisfactory as an intermediate type … .” But in the next sentence stated it “is not a satisfactory light machine gun for infantry use.” Reading between the lines of the Infantry Board report indicates that no more effort should be expended in trying to tweak the M1919A6 any further, and the document closed with the recommendation that the development of a better light machine gun be expedited. As events turned out, this didn’t happen until 1957 with the adoption of the M60 machine gun, which was intended to replace all the Browning .30-cal. machine guns, and the BAR, as standard issue. Throughout its service life, the M1919A6 was designated as “Limited Standard.”

Contracts were placed with the Saginaw Steering Gear Division of General Motors for the manufacture of the M1919A6. In 1944, 23,329 of the guns were made, with an additional 20,150 produced in 1945, for a total of 43,479. It was a simple matter to convert existing M1919A4s to M1919A6 configuration, and kits to accomplish this conversion in the field were produced.

Examples of M1919A4s modified to M1919A6 configuration have been noted with the last digit “4” being defaced and a “6” overstamped. It is not known how many were modified in this way. Also, later in the war, when many of the light tanks were withdrawn from service, the M1919A5 tank machine guns were removed and converted into M1919A4 or M1919A6 configuration, typically with the “5” similarly being overstamped to “4” or “6”.

The U.S. Army airborne units were issued M1919A6 machine guns, as it was felt that the gun would be better-suited for use by the paratroopers since it was lighter and did not require a tripod. They proved to be unpopular with many of its users. As is the case with most “compromise” arms, it didn’t really excel at any one thing. While it fired at a slightly higher cyclic rate than the M1919A4, it wasn’t any more effective in laying down fields of fire than its predecessor. The M1919A4 and the M2 tripod were carried by the gunner and assistant gunner, respectively, and the M1919A6 (which was heavier than the M1919A4 sans tripod) was carried by a single gunner. The M1919A6 could be mounted on the M2 tripod, but that would defeat the entire purpose of the gun. The gun was too heavy to be a true light machine gun, and it didn’t have the stability of a tripod-mounted gun.

There was a reason why the M1919A6 was always designated as “Limited Standard.” While it wasn’t horrendously bad, the M1919A6 simply wasn’t very good at its intended purpose of being a light and easily portable machine gun. There’s nothing wrong with trying to modify a design for uses other than those for which it was originally designed, but that doesn’t mean such efforts will always produce stellar results. The M1919A6’s major, if not sole, advantage was its ready availability. As stated, it was believed that the time required to design, test and manufacture an entirely new light machine gun would have taken too long.

It is a little-known fact that the Ordnance Dept. did embark on a program to produce a virtual copy of the excellent German MG42 machine gun chambered for the .30-’06 Sprg. cartridge. Such a gun would likely have filled the role envisioned for the M1919A6 superbly. However, these efforts did not work out very well. The developmental contract to fabricate a copy of the German MG42, to be designated as the “T-24,” was granted to the Saginaw Steering Gear Division of General Motors.

Like the M1919A6, the gun was envisioned as a replacement for the BAR and the M1919A4 machine gun and was designed so it could be used with the M2 tripod as well. The length of the American .30-cal. cartridge as compared the MG42’s 7.92×57 mm cartridge required that the German design essentially be re-engineered. However, the prototype gun functioned quite poorly in initial testing. It was soon discovered that a draftsman had not properly accounted for the differences in the dimensions between the American and German cartridges, and the receiver was about a 1/4″ too short, which resulted in the numerous malfunctions. The amount of additional engineering work to properly re-design the prototype was not considered to be worthwhile, and the project was canceled. This resulted in the gun being discarded and the M1919A6 being adopted instead. It has been suggested that there was an element of the “NIH (not invented here) Syndrome” involved in the decision to abandon the .30-cal. MG42 project and accept, albeit reluctantly, the M1919A6. It may not have been as good as a properly engineered .30-cal. MG42, but it was felt to be better than the alternative, which would have been nothing.

Like the M1919A4 machine gun it was based on, the M1919A6 remained in service well into the Vietnam War era. It is fair to say that the M1919A6 was not one of the best-loved American arms of World War II, even though the gun’s basic mechanism, the .30-cal. Browning, was held in high esteem. It has been said that the M1919A6 machine gun was akin to the old adage that “a camel was a horse designed by a committee.”

The foregoing was excerpted from the author’s comprehensive work U.S. Small Arms Of World War II. The 8 1/2″x11″ book contains 864 pps. and is lavishly illustrated. Contact: Mowbray Publishing, Inc.; (800) 999-4697; (gunandswordcollector.com).

The Art of War: Jungle Warfare

3,000 RPM on a bicycle! In September 2013, Sebastiaan Bowier set the flat-surface bicycle speed record at 83.13 miles per hour. That’s some serious pedal pushing.

I’m not sure who mounted a Villar Perosa M1915 machine gun on a bicycle, or when, or even why they did it. What I am sure of is that it has to be the greatest amount of firepower ever mounted aboard a bike. Regardless of how fast the cyclist can pedal, the Villar Perosa spits out 9 mm Glisenti ammo at up to 1,500 rounds per minute. Even I can do the math, and with its twin barrels, the little Italian dynamo rattles out up to 3,000 rounds per minute. Mama Mia, that’s 50 rounds per second!

The most common configuration of the M1915 Villar Perosa, equipped with a lightweight, folding bipod.

With just 25 rounds in each top-mounted magazine, the firer will only get a one-second squeeze on each of the thumb-button triggers on the Villar Perosa’s spade-grips. I have no data on speed-reloading Villar Perosa magazines while in the act of pedaling, but you’d likely get quite a workout riding back and forth from the ammunition dealer.

M1915 Villar Perosa on its transit case. Note the rear sight, built into the spade grips.

A relative unknown: The strange little M1915 Villar Perosa was the first true submachine gun in action during World War I. No one seemed to consider it a “subgun” though, and to be fair, no one really knew the category even existed at that time. Featuring the side-by-side coupling of identical guns, the Villar Perosa was usually operated as the world’s lightest crew-served weapon. The twin-gun arrangement weighs just slightly more than 14 lbs., with the occasional addition of an armored shield weighing far more than the weapon itself.

Troops firing the Villar Perosa though its weighty shield.

The “crew-served” description comes from the necessity to have several men focused on reloading the rapid-firing little weapon. I suspect that overheating would have been a significant problem during any extending firing. Various mounts were used, all seemingly more awkward than the next, this including an unconscionable shoulder-stock arrangement that kept the spade grips and the thumb-button triggers. Villar Perosa fires from an open bolt, on full-automatic only. Magazines are inserted from the top, and spent casings are ejected from the bottom. The sights are rudimentary: the rear sight is built into the spade grips, while the front sight is integrated into the front plate that joins the two barrels.

Austro-Hungarian troops with captured M1915 Villar Perosa SMGs. Note the lightweight tripod and metal baseplate.

Some attempts were made to mount the Villar Perosa on aircraft (as an observer’s weapon, and also placed on the upper wing for the pilot to use), but the 9 mm Glisenti rounds proved to be far too weak, lacking the range and penetrative power for air-to-air work. With all things considered, the bike mount makes as much sense as most wartime mountings for the M1915 Villar Perosa. Plus it is a helluva’ lot more manly than your average bicycle bell.

The M1915 Villar Perosa shown without the top-loading magazines. Note the centrally-mounted sights.

A design pointing to the future: Despite the Italians’ struggles to find a strong tactical application for their incredible little bullet-sprayer, the battlefield potential of the M1915 Villar Perosa was clear. The lightweight bipod and tripod mounts were most useful for the Alpini, Italy’s mountain troops that spent most of the Great War fighting the Austro-Hungarian forces in the Alps. The Villar Perosa’s suppressive fire capability was unmatched at that time. Sustained fire however, was a completely different story.

Austro-Hungarian troops with machine guns captured from the Italians: the French St Etienne Mle 1907 (left rear), the Vickers Mark I (right rear), the Lewis Mark II and the M1915 Villar Perosa.

During 1918, the twin barrels of the M1915 Villar Perosa were split up. The new OVP M1918 was redesigned as an automatic carbine, retaining the top-mounted magazine, and using new offset sights. Berretta also got involved, and adapted the Villar Perosa design to create its Model 1918 (the cyclic rate was brought down to a more manageable 900 rounds per minute). This was one of the world’s first conventional submachine guns. Of course, Berretta would go on to design many more SMGs, creating some of the best submachine guns of all time. Against this backdrop, the Villar Perosa would quietly fade into full-auto obscurity.

M1915 Villar Perosa showing details of its transit case: multiple 25-round magazines, and cleaning kit.