Category: Related Topics

|

||||||

Flanders Field

1. Have a bug-out kit ready at all times. Many of these folks packed at the last minute, grabbing whatever they thought they’d need. Needless to say, they forgot some important things (prescription medications, important documents, baby formula, diapers, etc.). Some of these things (e.g. prescriptions) obviously can’t be stocked up against possible emergency need, but you can at least have a list in your bug-out kit of what to grab at the last minute before you leave!

2. Renew supplies in your bug-out kit on a regular basis. Batteries lose their charge. Foods have an expiration date. So do common medications. Clothes can get moldy or dirty unless properly stored. All of these problems were found with the folks who kept backup or bug-out supplies on hand, and caused difficulties for them.

3. Plan on needing a LOT more supplies than you think. I found myself with over 30 people on hand, many of whom were not well supplied: and the stores were swamped with literally thousands of refugees, buying up everything in sight. I had enough supplies to keep myself going for 30 days. Guess what? Those supplies ended up keeping 30-odd people going for two days. I now know that I must plan on providing for not just myself, but others in need. I could have been selfish and said “No, these are mine” – but what good would that do in a real disaster? Someone would just try to take them, and then we’d have all the resulting unpleasantness. Far better to have extra supplies to share with others, whilst keeping your own core reserve intact (and, preferably, hidden from prying eyes!).

4. In a real emergency, forget about last-minute purchases. As I said earlier, the stores were swamped by thousands of refugees, as well as locals buying up last-minute supplies. If I hadn’t had my emergency supplies already, I would never have been able to buy them at the last minute. If I’d had to hit the road, the situation would have been even worse, as I’d be part of a stream of thousands of refugees, most of whom would be buying (or stealing) what they needed before I got to the store.

5. Make sure your vehicle will carry your essential supplies. Some of the folks who arrived at my place had tried to load up their cars with a humongous amount of stuff, only to find that they didn’t have space for themselves! Pets are a particular problem here, as they have to have air and light, and can’t be crammed into odd corners. If you have to carry a lot of supplies and a number of people, invest in a small luggage trailer or something similar (or a small travel trailer with space for your goodies) – it’ll pay dividends if the S really does HTF.

6. A big bug-out vehicle can be a handicap. Some of the folks arrived here with big pick-ups or SUV’s, towing equally large travel trailers. Guess what? On some evacuation routes, these huge combinations could not navigate corners very well, and/or were so difficult to turn that they ran into things (including other vehicles, which were NOT about to make way in the stress of an evacuation!). This led to hard feelings, harsh words, and at least one fist-fight. It’s not a bad idea to have smaller, more maneuverable vehicles, and a smaller travel trailer, so that one can “squeeze through” in a tight traffic situation. Another point: a big SUV or pickup burns a lot of fuel. This is bad news when there’s no fuel available! (See point 10 below.)

7. Make sure you have a bug-out place handy. I was fortunate in having enough ground (about 1.8 acres) to provide parking for all these RV’s and trailers, and to accommodate 11 small children in my living-room so that the adults could get some sleep on Sunday night, after many hours on the road in very heavy, slow-moving traffic. However, if I hadn’t had space, I would have unhesitatingly told the extra families to find somewhere else – and there wasn’t anywhere else here, that night. Even shops like Wal-Mart and K-Mart had trailers and RV’s backed up in their parking lots (which annoyed the heck out of shoppers trying to make last-minute purchases). Even on my property, I had no trailer sewage connections, so I had to tell the occupants that if they used their onboard toilets and showers, they had to drive their RV’s and trailers somewhere else to empty their waste tanks. If they hadn’t left this morning, they would have joined long, long lines to do this at local trailer parks (some of which were so overloaded by visiting trailers and RV’s that they refused to allow passers-by to use their dumping facilities).

8. Provide entertainment for younger children. Some of these families had young children (ranging from 3 months to 11 years). They had DVD’s, video games, etc. – but no power available in their trailers to show them! They had no coloring books, toys, etc. to keep the kids occupied. This was a bad mistake.

9. Pack essentials first, then luxuries. Many of these folks had packed mattresses off beds, comforters, cushions, bathrobes, etc. As a result, their vehicles were grossly overloaded, but often lacked real essentials like candles, non-perishable foods, etc. One family (both parents are gourmet cooks) packed eighteen (yes, EIGHTEEN!!!) special pots and pans, which they were going to use on a two-burner camp stove. They were horrified by my suggestion that under the circumstances, a nested stainless-steel camping cookware set would be rather more practical. “What? No omelet pan?” Sheesh…

10. Don’t plan on fuel being available en route. A number of my visitors had real problems finding gas to fill up on the road. With thousands of vehicles jammed nose-to-tail on four lanes of interstate, an awful lot of vehicles needed gas. By the time you got to a gas station, you were highly likely to find it sold out – or charging exorbitant prices, because the owners knew you didn’t have any choice but to pay what they asked. Much better to leave with a full tank of gas, and enough in spare containers to fill up on the road, if you have to, in order to reach your destination.

11. Have enough money with you for at least two weeks. Many of those who arrived here had very little in cash, relying on check-books and credit cards to fund their purchases. Guess what? Their small banks down in South Louisiana were all off-line, and their balances, credit authorizations, etc. could not be checked. As a result, many shops refused to accept their checks, and insisted on electronic verification before accepting their credit cards. Local banks also refused (initially) to cash checks for them, since they couldn’t check the status of their accounts on-line. Eventually (and very grudgingly) local banks began allowing them to cash checks for not more than $50-$100, depending on the bank. Fortunately, I have a reasonable amount of cash available at all times, so I was able to help some of them. I’m now going to increase my cash on hand, I think. Another thing – don’t bring only large bills. Many gas stations, convenience stores, etc. won’t accept anything larger than a $20 bill. Some of my guests had plenty of $100 bills, but couldn’t buy anything.

12. Don’t be sure that a disaster will be short-term. My friends have left now, heading south to Baton Rouge. They want to be closer to home for whenever they’re allowed to return. Unfortunately for them, the Governor has just announced the mandatory, complete evacuation of New Orleans, and there’s no word on when they will be allowed back. It will certainly be several weeks, and it might be several months. During that period, what they have with them – essential documents, clothing, etc. – is all they have. They’ll have to find new doctors to renew prescriptions; find a place to live (a FEMA trailer if they’re lucky – thousands of families will be lining up for these trailers); some way to earn a living (their jobs are gone with New Orleans, and I don’t see their employers paying them for not working when the employers aren’t making money either); and so on.

13. Don’t rely on government-run shelters if at all possible. Your weapons WILL be confiscated (yes, including pocket-knives, kitchen knives, and Leatherman-type tools); you’ll be crowded into close proximity with anyone and everyone (including some nice folks, but also including drug addicts, released convicts, gang members, and so on); you’ll be under the authority of the people running the shelter, who WILL call on law enforcement and military personnel to keep order (including stopping you leaving if you want to); and so on. Much, much better to have a place to go to, a plan to get there, and the supplies you need to do so on your own.

14. Warn your friends not to bring others with them!!! I had told two friends to bring themselves and their families to my home. They, unknown to me, told half-a-dozen other families to come too – “He’s a good guy, I’m sure he won’t mind!” Well, I did mind . . . but since the circumstances weren’t personally dangerous, I allowed them all to hang around. However, if things had been worse, I would have been very nasty indeed to their friends (and even nastier to them, for inviting others without clearing it with me first!). If you offer a place of refuge for your friends, make sure they know that this applies to them ONLY, not their other friends. Similarly, if you have someone willing to offer you refuge, don’t presume on his/her hospitality by arriving with others unforewarned.

15. Have account numbers, contact addresses and telephone numbers for all important persons and institutions. My friends will now have to get new postal addresses, and will have to notify others of this: their doctors, insurance companies (medical, personal, vehicle and property), bank(s), credit card issuer(s), utility supplier(s), telephone supplier(s), etc. – basically, anyone who sends them bills, or to whom they owe money, or who might owe them money. None of my friends brought all this information with them. Now, when they need to change postal addresses for correspondence, insurance claims, etc., how can they do this when they don’t know their account numbers, what number to call, who and where to write, etc.?

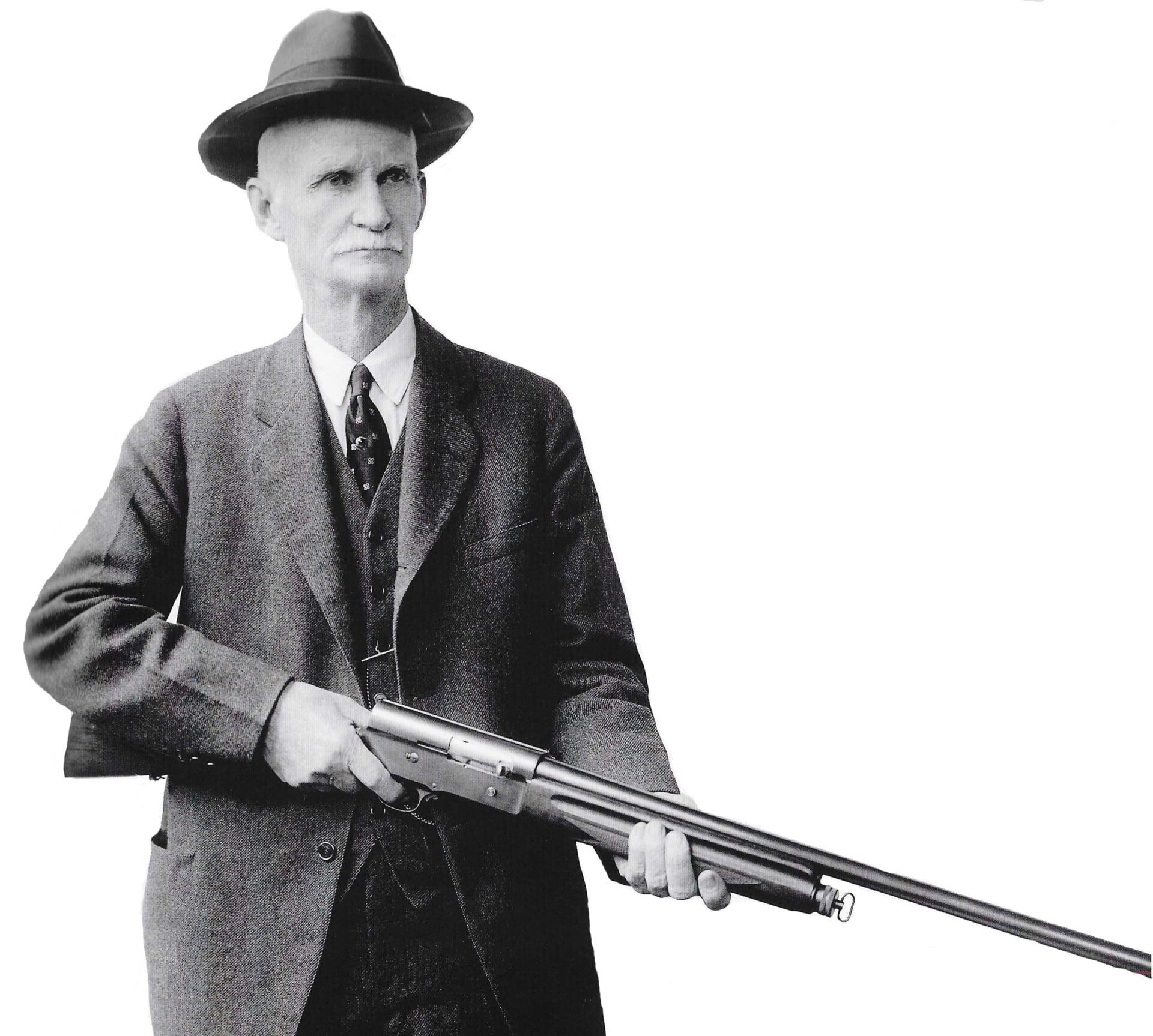

16. Have portable weapons and ammo ready to hand. Only two of my friends were armed, and one of them had only a handgun. The other had a handgun for himself, another for his wife, a shotgun, and an evil black rifle – MUCH better! I was asked by some of the other families, who’d seen TV reports of looting back in New Orleans, to lend them firearms. I refused, as they’d never handled guns before, and thus would have been more of a danger to themselves and other innocent persons than to looters. If they’d stayed a couple of days, so that I could teach them the basics, that would have been different: but they wouldn’t, so I didn’t. Another thing – you don’t have to take your entire arsenal along. Firearms for personal defense come first, then firearms for life support through hunting (and don’t forget the skinning knife!). A fishing outfit might not be a bad idea either (you can shoot something to use as bait, if necessary). Other than that, leave the rest of your guns in the safe (you do have a gun safe, securely bolted to the floor, don’t you?), and the bulk ammo supplies too. Bring enough ammo to keep you secure, but no more. If you really need bulk supplies of guns and ammo, they should be waiting for you at your bug-out location, not occupying space (and taking up a heck of a lot of weight!) in your vehicle. (For those bugging out in my direction, ammo supply will NOT be a problem . . . )

Here are some more ideas.

1. Route selection is very, very important. My friends (and their friends) basically looked at the map, found the shortest route to me, and followed it slavishly. This was a very bad idea, as something over half-a-million other folks had the same route in mind . . . Some of them took over twelve hours for what is usually a four-hour journey. If they’d used their heads, they would have seen (and heard, from radio reports) that going North up I-55 to Mississippi would have been much faster. There was less traffic on this route, and they could have turned left and hit Natchez, MS, and then cut across LA on Route 84. This would have taken them no more than five or six hours, even with the heavier evacuation traffic. Lesson: think outside the box, and don’t assume that the shortest route on the map in terms of distance will also be the shortest route in terms of time.

2. Keep in mind the social implications of a disaster situation. Feedback from my contacts in the Louisiana State Police (LSP) and other agencies is very worrying. They keep harping on the fact that the “underclass” that’s doing all the looting is almost exclusively Black and inner-city in composition. The remarks they’re reporting include such statements as “I’m entitled to this stuff!”, “This is payback time for all Whitey’s done to us”, and “This is reparations for slavery!”. Also, they’re blaming the present confused disaster-relief situation on racism. “Fo sho, if Whitey wuz sittin’ here in tha Dome waitin’ for help, no way would he be waitin’ like we is!” No, I’m not making up these comments… they are as reported by my law enforcement buddies.

This worries me very much. If we have such a divide in consciousness among our city residents, then when we hit a SHTF situation, we’re likely to be accused of racism, paternalism, oppression, and all sorts of other crimes just because we want to preserve law and order. If we, as individuals and families, provide for our own needs in emergency, and won’t share with others (whether they’re of another race or not) because we don’t have enough to go round, we’re likely to be accused of racism rather than pragmatism, and taking things from us can (and probably will) be justified as “Whitey getting his just desserts”. I’m absolutely not a racist, but the racial implications of the present situation are of great concern to me. The likes of Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, and the “reparations for slavery” brigade appear to have so polarized inner-city opinion that these folks are (IMHO) no longer capable of rational thought concerning such issues as looting, disaster relief, etc.

3. Implications for security. If one has successfully negotiated the danger zone, one will be in an environment filled, to a greater or lesser extent, with other evacuees. How many of them will have provided for their needs? How many of them will rely on obtaining from others (by hook or by crook) the things they need? In the absence of immediate State or relief-agency assistance, how many of them will feel “entitled” to obtain these necessities any way they have to, up to and including looting, murder and mayhem? Large gathering-places for refugees suddenly look rather less desirable . . . and being on one’s own, or in an isolated spot with one’s family, also looks less secure. One has to sleep sometime, and while one sleeps, one is vulnerable. Even one’s spouse and children might not be enough . . . there are always going to be vulnerabilities. One can hardly remain consciously in Condition Yellow while bathing children or making love! A team approach might be a viable solution here – see point 6 below.

4. There are “too many chiefs, not enough Indians” in New Orleans at the moment. The mayor has already blown his top about the levee breach: he claims that he had a plan in place to fix it by yesterday evening, but was overruled by the State government in Baton Rouge, who sent in others to do something different. This may or may not be true . . . My LSP buddies tell me that they’re getting conflicting assignments and/or requests from different organizations and individuals. One will send out a group to check a particular area for survivors: but when they get there, they find no-one, and later learn that another group has already checked and cleared the area. Unfortunately, in the absence of centralized command and control, the information is not being shared amongst all recovery teams. Also, there’s alleged to be conflict between City officials and State functionaries, with both sides claiming to be “running things”. Some individuals in the Red Cross, FEMA, and other groups appear to be refusing to take instructions from either side, instead (it’s claimed) wanting to run their own shows. This is allegedly producing catastrophic confusion and duplication of effort, and may even be making the loss of life worse, in that some areas in need of rescuers aren’t getting them. (I don’t know if the same problems are occurring in Mississippi and/or Alabama, but I wouldn’t be surprised if they were.) All of this is unofficial and off-the-record, but it doesn’t surprise me to hear it. Moral of the story: if you want to survive, don’t rely on the government or any government agency (or private relief organization, for that matter) to save you. Your survival is in your own hands – don’t drop it!

5. Long-term vision. This appears to be sadly lacking at present. Everyone is focused on the immediate, short-term objective of rescuing survivors. However, there are monumental problems looming, that need immediate attention, but don’t seem to be getting it right now. For example: the Port of Louisiana is the fifth-largest in the world, and vital to the economy, but the Coast Guard is saying (on TV) that they won’t be able to get it up and running for three to six months, because their primary focus is on search and rescue, and thereafter, disaster relief. Why isn’t the Coast Guard pulled off that job now, and put to work right away on something this critical? There are enough Navy, Marine and Air Force units available now to take over rescue missions.

Another example: there are over a million refugees from the Greater New Orleans area. They need accommodation and food, sure: but most of them are now unemployed, and won’t have any income at all for the next six to twelve months. There aren’t nearly enough jobs available in this area to absorb this workforce. What is being done to find work for them, even in states remote from the problem areas? The Government for sure won’t provide enough for them in emergency aid to be able to pay their bills. What about mortgages on properties that are now underwater? The occupants can’t and won’t pay, but the mortgage holders will demand payment. We could end up with massive foreclosures on property that is worthless, leaving a lot of folks neck-deep in debt and without homes (even damaged ones). What is being done to plan for this, and alleviate the problem as much as possible? I would have thought that the State government would have had at least the skeleton of an emergency plan for these sorts of things, and that FEMA would have the same, but this doesn’t seem to be the case. Why weren’t these things considered in the leisurely days pre-disaster, instead of erupting as immediate and unanswered needs post-disaster?

6. Personal emergency planning. This leads me to consider my own emergency planning. I’ve covered my own evacuation needs, and could probably survive with relative ease for between two weeks and one month: but what if I had been caught up in this mess? What would I do about earning a living, paying mortgages, etc.? If I can’t rely on the State, I for darn sure had better be able to rely on myself! I certainly need to re-examine my insurance policies, to ensure that if disaster strikes, my mortgage, major loans, etc. will be paid off (or that I will receive enough money to do this myself). I also need to provide for my physical security, and must ensure that I have supplies, skills and knowledge that will be “marketable” in exchange for hard currency in a post-disaster situation. The idea of a “team” of friends with (or to) whom to bug out, survive, etc. is looking better and better. Some of the team could take on the task of keeping a home maintained (even a camp-type facility), looking after kids, providing base security, etc. Others could be foraging for supplies, trading, etc. Still others could be earning a living for the whole team with their skills. In this way, we’d all contribute to our mutual survival and security in the medium to long term. Life might be a lot less comfortable than prior to the disaster, but at least we’d still have a life! This bears thinking about, and I might just have to start building “team relationships” with nearby people of like mind.

7. The “bank problem.” This bears consideration. I was at my bank this morning, depositing checks I’d been given by my visitors in exchange for cash. The teller warned me bluntly that it might be weeks before these checks could be credited to my account, as there was no way to clear them with their issuing banks, which were now under water and/or without communications facilities. He also told me that there had been an endless stream of folks trying to cash checks on South Louisiana banks, without success. He warned me that some of those banks will almost certainly fail, as they don’t have a single branch above water, and the customers and businesses they served are also gone – so checks drawn on them will eventually prove worthless. Even some major regional banks had run their Louisiana “hub” out of New Orleans, and now couldn’t access their records. I think it might be a good idea to have a “bug-out bank account” with a national bank, so that funds should be available anywhere they have a branch, rather than keeping all one’s money in a single bank (particularly a local one) or credit union. This is, of course, over and above one’s “bug-out stash” of ready cash.

8. Helping one’s friends is likely to prove expensive. I estimate that I’m out over $1,000 at the moment, partly from having all my supplies consumed, and partly from making cash available to friends who couldn’t cash their checks. I may or may not get some of this back in due course. I don’t mind it – if I were in a similar fix, I hope I could turn to my friends for help in the same way, after all – but I hadn’t made allowance for it. I shall have to do so in future, as well as planning to contribute to costs incurred by those who offer me hospitality under similar circumstances.