New York City has always been pretty congested.

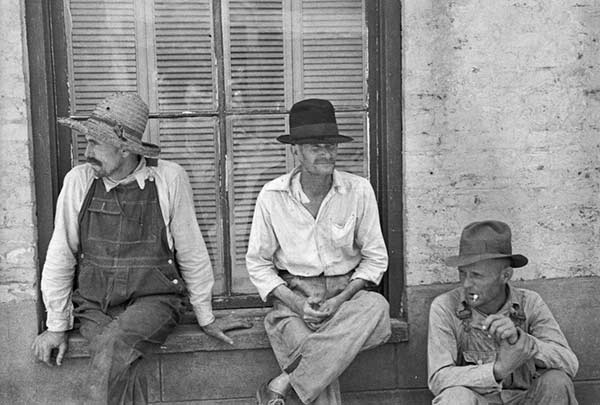

This picture dates back to the 1930s.

The news this morning sported yet another headline trumpeting the sordid state of my countrymen living in New York City. It seems every day brings some fresh new tragedy from some Leftist enclave overrun with homelessness, drug abuse, crime, violence and despair. In this case, some well-to-do woman was walking back to her building when she was accosted by a pair of muggers.

The criminals threw the poor woman against the building and snatched away her purse and phone. The many bystanders present just looked on with disinterest. What made the event newsworthy was that the doorman at her building actually chose to intervene. He shooed away the two miscreants and escorted the shaken woman inside. The two scumbags strolled away laughing as they cataloged their new swag. Oddly, that sort of thing really doesn’t happen down here in the Deep South where I live.

I don’t much want to live in New York City myself. However, the

Statue of Liberty is pretty darn awesome, so there’s that.

Photo by MCJ1800 / Wikipedia

Daylight and Dark

Far be it from me to insinuate that one part of our great republic is superior to any other. I freely admit that, in addition to more than 90,000 homeless people and roughly half a million illegal immigrants, the Big Apple also plays host to the Statue of Liberty. That is indeed pretty darn cool.

My own home state of Mississippi admittedly rates 47th in literacy. Only New Mexico, Texas and California beat us in our race to the bottom. Incidentally, New York is 43rd.

Mine is still a pretty Godly state. We are number one in the country for adults who pray daily and believe in God. We are fourth in church attendance. Additionally, Everytown for Gun Safety, a rabid mob of freedom-averse gun-hating hoplophobes, rates us 49th for gun law strength. I’m pretty proud of that myself.

Every single day at work, I see some redneck guy in my medical clinic and ask him to shed his jacket or vest so I can listen to his chest. That’s when I see it. The next question is invariably, “What you packing?”

I already know the answer to that question, of course, but it is a great way to start a conversation. And that is why we don’t have thugs throwing women up against buildings on the square in Oxford, Mississippi. It is not hyperbole to say that the first time you do that around here, half a dozen armed rednecks are just going to blow you away.

Mine is a constitutional carry state. Down here, your birth certificate is your concealed carry license. We also really love our cops, and they love us. The local fuzz is forever offering free classes on self-defense for women and similar civic-minded stuff. My wife took it. That was great until she got home and wanted to practice what she learned on me.

We had to call the cops a few years ago for a disturbance in the waiting room. Some crazy person was getting out of hand. It happens. One of the responding officers actually arrived on horseback. He had been across the street showing off his police horse at the nearby nursing home when he got the call.

Rednecks are a timeless part of the Deep South. These were photographed back in the early 20th century. However, guys like this are tough, they love America, and they will not stand idly by while women get beat up.

Find a Need and Fill It

If random armed rednecks are a deterrent to crime, that seems like an opportunity to me. We have plenty of armed rednecks down here in Mississippi, while our friends in New York appear to have a relative dearth. As such, I would like to announce my newest business venture. I call it Will’s Redneck Rentals. We gladly export.

Here is one of our hypothetical armed rednecks available for rent — Colt Thompson (I actually know a guy down here named Colt Thompson) has worked for the past 15 years as an electrician. He is 40 pounds overweight, married and has three children. He was a Bud Light man until last year when he inexplicably switched to Coors. His preferred carry piece is a 9mm Springfield Armory Hellcat in a well-used CrossBreed IWB rig. He’s looking for a side gig to help keep things spicy.

Nowadays, Colt is an overweight middle-aged redneck. However, right out of high school, he spent four years in a Ranger battalion. He still shoots regularly and recreationally. That fat, unassuming HVAC repairman can run that Hellcat like a Delta Force commando. He also loves America, goes to church regularly and absolutely hates people who pick on women, like viscerally. Give the guy a cot and keep him in food and beer, and he’s yours for as long as you need him.

So, surf on over to www.mississippiactuallysoundsprettyfreakingawesome.com to sign up for your own rental redneck. We deliver. Additionally, if you are the sort who shakes down women in public spaces, be forewarned. Try that in front of Colt Thompson or one of his peers, and that guy is going to kill you deader than rocks. We guarantee it.

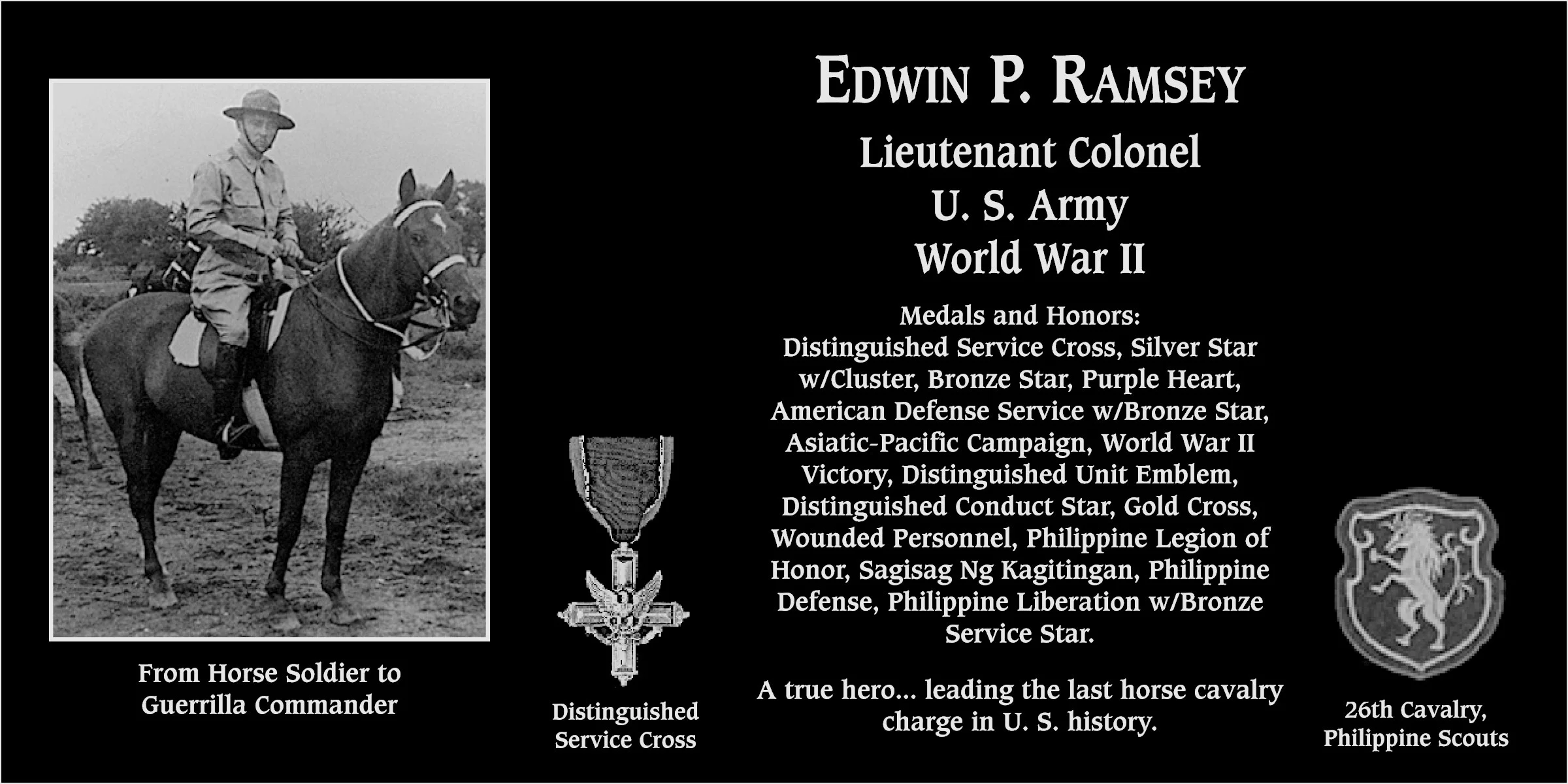

Ramsey quickly signaled his men to deploy into forager formation. Then he raised his pistol and shouted, “Charge!” With troops firing their pistols, the galloping cavalry horses smashed into the surprised enemy soldiers, routing them.

Ramsey quickly signaled his men to deploy into forager formation. Then he raised his pistol and shouted, “Charge!” With troops firing their pistols, the galloping cavalry horses smashed into the surprised enemy soldiers, routing them.

.PNG)

.JPG)