https://youtu.be/w-tz-9c-g4A

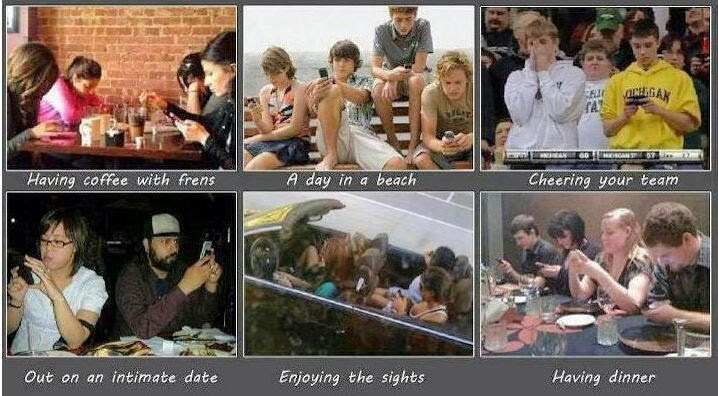

I still can not figure out WTF happened from then to now. Any ideas / solutions from my Fantastic readers out there?

Category: Other Stuff

May God Bless us all! Grumpy

Happy Halloween !

Also if you were just wondering why we did this :

Halloween

| Halloween | |

|---|---|

A jack-o’-lantern, one of the symbols of Halloween

|

|

| Also called | Hallowe’en Allhallowe’en All Hallows’ Eve All Saints’ Eve |

| Observed by | Western Christians and many non-Christians around the world[1] |

| Significance | First day of Allhallowtide |

| Celebrations | Trick-or-treating, costumeparties, making jack-o’-lanterns, lighting bonfires, divination, apple bobbing, visiting haunted attractions |

| Observances | Church services,[2] prayer,[3]fasting,[1] and vigil[4] |

| Date | 31 October |

| Related to | Totensonntag, Blue Christmas, Thursday of the Dead, Samhain, Hop-tu-Naa, Calan Gaeaf, Allantide, Day of the Dead, Reformation Day, All Saints’ Day, Mischief Night(cf. vigils) |

Halloween or Hallowe’en (a contraction of All Hallows‘ Evening),[5] also known as Allhalloween,[6] All Hallows’ Eve,[7] or All Saints’ Eve,[8] is a celebration observed in a number of countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Hallows’ Day and Reformation Day. It begins the three-day observance of Allhallowtide,[9] the time in the liturgical yeardedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed.[10][11]

It is widely believed that many Halloween traditions originated from Celticharvest festivals that may have pagan roots, particularly the Gaelic festival Samhain, and that this festival was Christianized as Halloween.[1][7][12][13][14][15] Some academics, however, support the view that Halloween began independently as a solely Christian holiday.[1][16][17][18][19]

Halloween activities include trick-or-treating (or the related guising), attending Halloween costume parties, carving pumpkins into jack-o’-lanterns, lighting bonfires, apple bobbing, divination games, playing pranks, visiting haunted attractions, telling scary stories and watching horror films. In many parts of the world, the Christian religious observances of All Hallows’ Eve, including attending church services and lighting candles on the graves of the dead, remain popular,[20][21][22] although elsewhere it is a more commercial and secular celebration.[23][24][25] Some Christians historically abstained from meat on All Hallows’ Eve, a tradition reflected in the eating of certain vegetarian foods on this vigil day, including apples, potato pancakes, and soul cakes.[26][27][28][29]

Contents

[hide]

Etymology

The word Halloween or Hallowe’en dates to about 1745[30] and is of Christian origin.[31] The word “Hallowe’en” means “hallowed evening” or “holy evening”.[32] It comes from a Scottish term for All Hallows’ Eve (the evening before All Hallows’ Day).[33] In Scots, the word “eve” is even, and this is contracted to e’en or een. Over time, (All) Hallow(s) E(v)en evolved into Hallowe’en. Although the phrase “All Hallows'” is found in Old English “All Hallows’ Eve” is itself not seen until 1556.[33][34]

History

Gaelic and Welsh influence

An early 20th-century Irish Halloween mask displayed at the Museum of Country Life.

Today’s Halloween customs are thought to have been influenced by folk customs and beliefs from the Celtic-speaking countries, some of which are believed to have paganroots.[35][36] Jack Santino, a folklorist, writes that “there was throughout Ireland an uneasy truce existing between customs and beliefs associated with Christianity and those associated with religions that were Irish before Christianity arrived”.[37]Historian Nicholas Rogers, exploring the origins of Halloween, notes that while “some folklorists have detected its origins in the Roman feast of Pomona, the goddess of fruits and seeds, or in the festival of the dead called Parentalia, it is more typically linked to the Celtic festival of Samhain, which comes from the Old Irish for “summer’s end”.[35]

Samhain (pronounced /ˈsɑːwɪn/ SAH-win or /ˈsaʊ.ɪn/ SOW-in) was the first and most important of the four quarter days in the medieval Gaelic calendar and was celebrated on 31 October–1 November in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man.[38][39]A kindred festival was held at the same time of year by the Brittonic Celts, called Calan Gaeaf in Wales, Kalan Gwav in Cornwall and Kalan Goañv in Brittany; a name meaning “first day of winter”. For the Celts, the day ended and began at sunset; thus the festival began on the evening before 1 November by modern reckoning.[40] Samhain and Calan Gaeaf are mentioned in some of the earliest Irish and Welsh literature. The names have been used by historians to refer to Celtic Halloween customs up until the 19th century,[41] and are still the Gaelic and Welsh names for Halloween.

Snap-Apple Night, painted by Daniel Maclise in 1833, shows people feasting and playing divination games on Halloween in Ireland.

Samhain/Calan Gaeaf marked the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter or the ‘darker half’ of the year.[42][43] Like Beltane/Calan Mai, it was seen as a liminal time, when the boundary between this world and the Otherworld thinned. This meant the Aos Sí (pronounced /iːˈʃiː/ ees-SHEE), the ‘spirits‘ or ‘fairies‘, could more easily come into our world and were particularly active.[44][45] Most scholars see the Aos Sí as “degraded versions of ancient gods […] whose power remained active in the people’s minds even after they had been officially replaced by later religious beliefs”. The Aos Síwere both respected and feared, with individuals often invoking the protection of God when approaching their dwellings.[46][47] At Samhain, it was believed that the Aos Sí needed to be propitiated to ensure that the people and their livestock survived the winter. Offerings of food and drink, or portions of the crops, were left outside for the Aos Sí.[48][49][50] The souls of the dead were also said to revisit their homes seeking hospitality.[51] Places were set at the dinner table and by the fire to welcome them.[52] The belief that the souls of the dead return home on one night of the year and must be appeased seems to have ancient origins and is found in many cultures throughout the world.[53] In 19th century Ireland, “candles would be lit and prayers formally offered for the souls of the dead. After this the eating, drinking, and games would begin”.[54]

Throughout Ireland and Britain, the household festivities included rituals and games intended to foretell one’s future, especially regarding death and marriage.[55] Apples and nuts were often used in these divination rituals. They included apple bobbing, nut roasting, scrying or mirror-gazing, pouring molten lead or egg whites into water, dream interpretation, and others.[56] Special bonfires were lit and there were rituals involving them. Their flames, smoke and ashes were deemed to have protective and cleansing powers, and were also used for divination.[41][42] In some places, torches lit from the bonfire were carried sunwise around homes and fields to protect them.[41] It is suggested that the fires were a kind of imitative or sympathetic magic – they mimicked the Sun, helping the “powers of growth” and holding back the decay and darkness of winter.[52][57][58] In Scotland, these bonfires and divination games were banned by the church elders in some parishes.[59] Later, these bonfires served to keep “away the devil“.[60]

A traditional Irish Halloween turnip (rutabaga) lantern on display in the Museum of Country Life, Ireland

From at least the 16th century,[61] the festival included mumming and guising in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man and Wales.[62] This involved people going house-to-house in costume (or in disguise), usually reciting verses or songs in exchange for food.[62] It may have originally been a tradition whereby people impersonated the Aos Sí, or the souls of the dead, and received offerings on their behalf, similar to the custom of souling (see below). Impersonating these beings, or wearing a disguise, was also believed to protect oneself from them.[63] It is suggested that the mummers and guisers “personify the old spirits of the winter, who demanded reward in exchange for good fortune”.[64] In parts of southern Ireland, the guisers included a hobby horse. A man dressed as a Láir Bhán (white mare) led youths house-to-house reciting verses—some of which had pagan overtones—in exchange for food. If the household donated food it could expect good fortune from the ‘Muck Olla’; not doing so would bring misfortune.[65] In Scotland, youths went house-to-house with masked, painted or blackened faces, often threatening to do mischief if they were not welcomed.[62] F. Marian McNeill suggests the ancient festival included people in costume representing the spirits, and that faces were marked (or blackened) with ashes taken from the sacred bonfire.[61] In parts of Wales, men went about dressed as fearsome beings called gwrachod.[62]

In the late 19th and early 20th century, young people in Glamorgan and Orkney cross-dressed.[62] Elsewhere in Europe, mumming and hobby horses were part of other yearly festivals. However, in the Celtic-speaking regions they were “particularly appropriate to a night upon which supernatural beings were said to be abroad and could be imitated or warded off by human wanderers”.[62] From at least the 18th century, “imitating malignant spirits” led to playing pranks in Ireland and the Scottish Highlands.[62] Wearing costumes and playing pranks at Halloween spread to England in the 20th century.[62] Traditionally, pranksters used hollowed out turnips or mangel wurzels often carved with grotesque faces as lanterns.[62] By those who made them, the lanterns were variously said to represent the spirits,[62] or were used to ward offevil spirits.[66][67] They were common in parts of Ireland and the Scottish Highlands in the 19th century,[62] as well as in Somerset (see Punkie Night). In the 20th century they spread to other parts of England and became generally known as jack-o’-lanterns.[62]

Christian influence

Today’s Halloween customs are also thought to have been influenced by Christian dogma and practices derived from it. Halloween is the evening before the Christian holy days of All Hallows’ Day (also known as All Saints’ or Hallowmas) on 1 November and All Souls’ Day on 2 November, thus giving the holiday on 31 October the full name of All Hallows’ Eve(meaning the evening before All Hallows’ Day).[68] Since the time of the early Church,[69] major feasts in Christianity (such as Christmas, Easter and Pentecost) had vigils that began the night before, as did the feast of All Hallows’.[70] These three days are collectively called Allhallowtide and are a time for honoring the saints and praying for the recently departed soulswho have yet to reach Heaven. Commemorations of all saints and martyrs were held by several churches on various dates, mostly in springtime.[71] In 609, Pope Boniface IV re-dedicated the Pantheon in Rome to “St Mary and all martyrs” on 13 May. This was the same date as Lemuria, an ancient Roman festival of the dead, and the same date as the commemoration of all saints in Edessa in the time of Ephrem.[72]

The feast of All Hallows’, on its current date in the Western Church, may be traced to Pope Gregory III‘s (731–741) founding of an oratory in St Peter’s for the relics “of the holy apostles and of all saints, martyrs and confessors”.[73][74] In 835, All Hallows’ Day was officially switched to 1 November, the same date as Samhain, at the behest of Pope Gregory IV.[75] Some suggest this was due to Celtic influence, while others suggest it was a Germanic idea,[75] although it is claimed that both Germanic and Celtic-speaking peoples commemorated the dead at the beginning of winter.[76] They may have seen it as the most fitting time to do so, as it is a time of ‘dying’ in nature.[75][76] It is also suggested that the change was made on the “practical grounds that Rome in summer could not accommodate the great number of pilgrims who flocked to it”, and perhaps because of public health considerations regarding Roman Fever – a disease that claimed a number of lives during the sultry summers of the region.[77]

By the end of the 12th century they had become holy days of obligationacross Europe and involved such traditions as ringing church bells for the souls in purgatory. In addition, “it was customary for criers dressed in black to parade the streets, ringing a bell of mournful sound and calling on all good Christians to remember the poor souls.”[79] “Souling”, the custom of baking and sharing soul cakes for all christened souls,[80] has been suggested as the origin of trick-or-treating.[81] The custom dates back at least as far as the 15th century[82] and was found in parts of England, Flanders, Germany and Austria.[53] Groups of poor people, often children, would go door-to-door during Allhallowtide, collecting soul cakes, in exchange for praying for the dead, especially the souls of the givers’ friends and relatives.[82][83][84] Soul cakes would also be offered for the souls themselves to eat,[53] or the ‘soulers’ would act as their representatives.[85] As with the Lenten tradition of hot cross buns, Allhallowtide soul cakes were often marked with a cross, indicating that they were baked as alms.[86] Shakespeare mentions souling in his comedy The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1593).[87] On the custom of wearing costumes, Christian minister Prince Sorie Conteh wrote: “It was traditionally believed that the souls of the departed wandered the earth until All Saints’ Day, and All Hallows’ Eve provided one last chance for the dead to gain vengeance on their enemies before moving to the next world. In order to avoid being recognized by any soul that might be seeking such vengeance, people would don masks or costumes to disguise their identities”.[88]

It is claimed that in the Middle Ages, churches that were too poor to display the relics of martyred saints at Allhallowtide let parishioners dress up as saints instead.[89] Some Christians observe this custom at Halloween today.[90] Lesley Bannatyne believes this could have been a Christianization of an earlier pagan custom.[91] It has been suggested that the carved jack-o’-lantern, a popular symbol of Halloween, originally represented the souls of the dead.[92] On Halloween, in medieval Europe, “fires [were] lit to guide these souls on their way and deflect them from haunting honest Christian folk.”[93] Households in Austria, England and Ireland often had “candles burning in every room to guide the souls back to visit their earthly homes”. These were known as “soul lights”.[94][95][96] Many Christians in mainland Europe, especially in France, believed “that once a year, on Hallowe’en, the dead of the churchyards rose for one wild, hideous carnival” known as the danse macabre, which has often been depicted in church decoration.[97] Christopher Allmand and Rosamond McKitterick write in The New Cambridge Medieval History that “Christians were moved by the sight of the Infant Jesus playing on his mother’s knee; their hearts were touched by the Pietà; and patron saints reassured them by their presence. But, all the while, the danse macabreurged them not to forget the end of all earthly things.”[98] An article published by Christianity Today claimed that the danse macabre was enacted at village pageants and at court masques, with people “dressing up as corpses from various strata of society”, and suggested this was the origin of modern-day Halloween costume parties.[99][100]

In parts of Britain, these customs came under attack during the Reformation as some Protestants berated purgatory as a “popish” doctrine incompatible with their notion of predestination. Thus, for some Nonconformist Protestants, the theologyof All Hallows’ Eve was redefined; without the doctrine of purgatory, “the returning souls cannot be journeying from Purgatory on their way to Heaven, as Catholics frequently believe and assert. Instead, the so-called ghosts are thought to be in actuality evil spirits. As such they are threatening.”[95] Other Protestants maintained belief in an intermediate state, known as Hades (Bosom of Abraham),[101] and continued to observe the original customs, especially souling, candlelitprocessions and the ringing of church bells in memory of the dead.[68][102] With regard to the evil spirits, on Halloween, “barns and homes were blessed to protect people and livestock from the effect of witches, who were believed to accompany the malignant spirits as they traveled the earth.”[93] In the 19th century, in some rural parts of England, families gathered on hills on the night of All Hallows’ Eve. One held a bunch of burning straw on a pitchfork while the rest knelt around him in a circle, praying for the souls of relatives and friends until the flames went out. This was known as teen’lay, derived either from the Old English tendan (to kindle) or a word related to Old Irish tenlach (hearth).[103] The rising popularity of Guy Fawkes Night (5 November) from 1605 onward, saw many Halloween traditions appropriated by that holiday instead, and Halloween’s popularity waned in Britain, with the noteworthy exception of Scotland.[104] There and in Ireland, they had been celebrating Samhain and Halloween since at least the early Middle Ages, and the Scottish kirk took a more pragmatic approach to Halloween, seeing it as important to the life cycle and rites of passage of communities and thus ensuring its survival in the country.[104]

In France, some Christian families, on the night of All Hallows’ Eve, prayed beside the graves of their loved ones, setting down dishes full of milk for them.[94] On Halloween, in Italy, some families left a large meal out for ghosts of their passed relatives, before they departed for church services.[105] In Spain, on this night, special pastries are baked, known as “bones of the holy” (Spanish: Huesos de Santo) and put them on the graves of the churchyard, a practice that continues to this day.[106]

Spread to North America

The annual Greenwich Village Halloween Parade in New York City is the world’s largest Halloween parade.[107]

Lesley Bannatyne and Cindy Ott both write that Anglican colonists in the Southern United States and Catholic colonists in Maryland “recognized All Hallow’s Eve in their church calendars”,[108][109] although the Puritans of New England maintained strong opposition to the holiday, along with other traditional celebrations of the established Church, including Christmas.[110]Almanacs of the late 18th and early 19th century give no indication that Halloween was widely celebrated in North America.[111] It was not until mass Irish and Scottish immigration in the 19th century that Halloween became a major holiday in North America.[111] Confined to the immigrant communities during the mid-19th century, it was gradually assimilated into mainstream society and by the first decade of the 20th century it was being celebrated coast to coast by people of all social, racial and religious backgrounds.[112]“In Cajun areas, a nocturnal Mass was said in cemeteries on Halloween night. Candles that had been blessed were placed on graves, and families sometimes spent the entire night at the graveside”.[113]

Symbols

At Halloween, yards, public spaces, and some houses may be decorated with traditionally macabre symbols including witches, skeletons, ghosts, cobwebs, and headstones.

Development of artifacts and symbols associated with Halloween formed over time. Jack-o’-lanterns are traditionally carried by guisers on All Hallows’ Eve in order to frighten evil spirits.[92][114] There is a popular Irish Christian folktale associated with the jack-o’-lantern,[115] which in folklore is said to represent a “soul who has been denied entry into both heaven and hell“:[116]

On route home after a night’s drinking, Jack encounters the Devil and tricks him into climbing a tree. A quick-thinking Jack etches the sign of the cross into the bark, thus trapping the Devil. Jack strikes a bargain that Satan can never claim his soul. After a life of sin, drink, and mendacity, Jack is refused entry to heaven when he dies. Keeping his promise, the Devil refuses to let Jack into hell and throws a live coal straight from the fires of hell at him. It was a cold night, so Jack places the coal in a hollowed out turnip to stop it from going out, since which time Jack and his lantern have been roaming looking for a place to rest.[117]

In Ireland and Scotland, the turnip has traditionally been carved during Halloween,[118][119] but immigrants to North America used the native pumpkin, which is both much softer and much larger – making it easier to carve than a turnip.[118]The American tradition of carving pumpkins is recorded in 1837[120] and was originally associated with harvest time in general, not becoming specifically associated with Halloween until the mid-to-late 19th century.[121]

Decorated house in Weatherly, Pennsylvania

The modern imagery of Halloween comes from many sources, including Christian eschatology, national customs, works of Gothic and horrorliterature (such as the novels Frankenstein and Dracula) and classic horror films (such as Frankenstein and The Mummy).[122][123] Imagery of the skull, a reference to Golgotha in the Christian tradition, serves as “a reminder of death and the transitory quality of human life” and is consequently found in memento mori and vanitas compositions;[124] skulls have therefore been commonplace in Halloween, which touches on this theme.[125] Traditionally, the back walls of churches are “decorated with a depiction of the Last Judgment, complete with graves opening and the dead rising, with a heaven filled with angels and a hell filled with devils”, a motif that has permeated the observance of this triduum.[126] One of the earliest works on the subject of Halloween is from Scottish poet John Mayne, who, in 1780, made note of pranks at Halloween; “What fearfu’ pranks ensue!”, as well as the supernatural associated with the night, “Bogies” (ghosts), influencing Robert Burns‘ “Halloween” (1785).[127] Elements of the autumn season, such as pumpkins, corn husks, and scarecrows, are also prevalent. Homes are often decorated with these types of symbols around Halloween. Halloween imagery includes themes of death, evil, and mythical monsters.[128] Black, orange, and sometimes purple are Halloween’s traditional colors.

Trick-or-treating and guising

Trick-or-treaters in Sweden

Trick-or-treating is a customary celebration for children on Halloween. Children go in costume from house to house, asking for treats such as candy or sometimes money, with the question, “Trick or treat?” The word “trick” implies a “threat” to perform mischief on the homeowners or their property if no treat is given.[81] The practice is said to have roots in the medieval practice of mumming, which is closely related to souling.[129] John Pymm writes that “many of the feast days associated with the presentation of mumming plays were celebrated by the Christian Church.”[130] These feast days included All Hallows’ Eve, Christmas, Twelfth Night and Shrove Tuesday.[131][132] Mumming practiced in Germany, Scandinavia and other parts of Europe,[133] involved masked persons in fancy dress who “paraded the streets and entered houses to dance or play dice in silence”.[134]

In England, from the medieval period,[135] up until the 1930s,[136] people practiced the Christian custom of souling on Halloween, which involved groups of soulers, both Protestant and Catholic,[102] going from parish to parish, begging the rich for soul cakes, in exchange for praying for the souls of the givers and their friends.[83] In Scotland and Ireland, guising – children disguised in costume going from door to door for food or coins – is a traditional Halloween custom, and is recorded in Scotland at Halloween in 1895 where masqueraders in disguise carrying lanterns made out of scooped out turnips, visit homes to be rewarded with cakes, fruit, and money.[119] The practice of guising at Halloween in North America is first recorded in 1911, where a newspaper in Kingston, Ontario reported children going “guising” around the neighborhood.[137]

American historian and author Ruth Edna Kelley of Massachusetts wrote the first book-length history of Halloween in the US; The Book of Hallowe’en (1919), and references souling in the chapter “Hallowe’en in America”.[138] In her book, Kelley touches on customs that arrived from across the Atlantic; “Americans have fostered them, and are making this an occasion something like what it must have been in its best days overseas. All Halloween customs in the United States are borrowed directly or adapted from those of other countries”.[139]

While the first reference to “guising” in North America occurs in 1911, another reference to ritual begging on Halloween appears, place unknown, in 1915, with a third reference in Chicago in 1920.[140] The earliest known use in print of the term “trick or treat” appears in 1927, in the Blackie Herald Alberta, Canada.[141]

The thousands of Halloween postcards produced between the turn of the 20th century and the 1920s commonly show children but not trick-or-treating.[142] Trick-or-treating does not seem to have become a widespread practice until the 1930s, with the first U.S. appearances of the term in 1934,[143] and the first use in a national publication occurring in 1939.[144]

An automobile trunk at a trunk-or-treat event at St. John Lutheran Church and Early Learning Center in Darien, Illinois

A popular variant of trick-or-treating, known as trunk-or-treating (or Halloween tailgaiting), occurs when “children are offered treats from the trunks of cars parked in a church parking lot”, or sometimes, a school parking lot.[106][145] In a trunk-or-treat event, the trunk (boot) of each automobile is decorated with a certain theme,[146] such as those of children’s literature, movies, scripture, and job roles.[147] Trunk-or-treating has grown in popularity due to its perception as being more safe than going door to door, a point that resonates well with parents, as well as the fact that it “solves the rural conundrum in which homes [are] built a half-mile apart”.[148][149]

Costumes

Halloween costumes are traditionally modeled after supernatural figures such as vampires, monsters, ghosts, skeletons, witches, and devils. Over time, in the United States, the costume selection extended to include popular characters from fiction, celebrities, and generic archetypes such as ninjas and princesses.[81]

Dressing up in costumes and going “guising” was prevalent in Ireland and Scotland at Halloween by the late 19th century.[119] Costuming became popular for Halloween parties in the US in the early 20th century, as often for adults as for children. The first mass-produced Halloween costumes appeared in stores in the 1930s when trick-or-treating was becoming popular in the United States.

The yearly New York Halloween Parade, begun in 1974 by puppeteer and mask maker Ralph Lee of Greenwich Village, is the world’s largest Halloween parade and one of America’s only major nighttime parades (along with Portland’s Starlight Parade), attracting more than 60,000 costumed participants, two million spectators, and a worldwide television audience of over 100 million.[107]

Eddie J. Smith, in his book Halloween, Hallowed is Thy Name, offers a religious perspective to the wearing of costumes on All Hallows’ Eve, suggesting that by dressing up as creatures “who at one time caused us to fear and tremble”, people are able to poke fun at Satan “whose kingdom has been plundered by our Saviour”. Images of skeletons and the dead are traditional decorations used as memento mori.[150][151]

“Trick-or-Treat for UNICEF” is a fundraising program to support UNICEF,[81] a United Nations Programme that provides humanitarian aid to children in developing countries. Started as a local event in a Northeast Philadelphia neighborhood in 1950 and expanded nationally in 1952, the program involves the distribution of small boxes by schools (or in modern times, corporate sponsors like Hallmark, at their licensed stores) to trick-or-treaters, in which they can solicit small-change donations from the houses they visit. It is estimated that children have collected more than $118 million for UNICEF since its inception. In Canada, in 2006, UNICEF decided to discontinue their Halloween collection boxes, citing safety and administrative concerns; after consultation with schools, they instead redesigned the program.[152][153]

Games and other activities

In this 1904 Halloween greeting card, divination is depicted: the young woman looking into a mirror in a darkened room hopes to catch a glimpse of her future husband.

There are several games traditionally associated with Halloween. Some of these games originated as divination rituals or ways of foretelling one’s future, especially regarding death, marriage and children. During the Middle Ages, these rituals were done by a “rare few” in rural communities as they were considered to be “deadly serious” practices.[154] In recent centuries, these divination games have been “a common feature of the household festivities” in Ireland and Britain.[55]They often involve apples and hazelnuts. In Celtic mythology, apples were strongly associated with the Otherworld and immortality, while hazelnutswere associated with divine wisdom.[155] Some also suggest that they derive from Roman practices in celebration of Pomona.[81]

The following activities were a common feature of Halloween in Ireland and Britain during the 17th–20th centuries. Some have become more widespread and continue to be popular today. One common game is apple bobbing or dunking (which may be called “dooking” in Scotland)[156] in which apples float in a tub or a large basin of water and the participants must use only their teeth to remove an apple from the basin. A variant of dunking involves kneeling on a chair, holding a fork between the teeth and trying to drive the fork into an apple. Another common game involves hanging up treacle or syrup-coated scones by strings; these must be eaten without using hands while they remain attached to the string, an activity that inevitably leads to a sticky face. Another once-popular game involves hanging a small wooden rod from the ceiling at head height, with a lit candle on one end and an apple hanging from the other. The rod is spun round and everyone takes turns to try to catch the apple with their teeth.[157]

Several of the traditional activities from Ireland and Britain involve foretelling one’s future partner or spouse. An apple would be peeled in one long strip, then the peel tossed over the shoulder. The peel is believed to land in the shape of the first letter of the future spouse’s name.[158][159] Two hazelnuts would be roasted near a fire; one named for the person roasting them and the other for the person they desire. If the nuts jump away from the heat, it is a bad sign, but if the nuts roast quietly it foretells a good match.[160][161] A salty oatmeal bannock would be baked; the person would eat it in three bites and then go to bed in silence without anything to drink. This is said to result in a dream in which their future spouse offers them a drink to quench their thirst.[162] Unmarried women were told that if they sat in a darkened room and gazed into a mirror on Halloween night, the face of their future husband would appear in the mirror.[163] However, if they were destined to die before marriage, a skull would appear. The custom was widespread enough to be commemorated on greeting cards[164] from the late 19th century and early 20th century.

In Ireland and Scotland, items would be hidden in food—usually a cake, barmbrack, cranachan, champ or colcannon—and portions of it served out at random. A person’s future would be foretold by the item they happened to find; for example, a ring meant marriage and a coin meant wealth.[165]

Up until the 19th century, the Halloween bonfires were also used for divination in parts of Scotland, Wales and Brittany. When the fire died down, a ring of stones would be laid in the ashes, one for each person. In the morning, if any stone was mislaid it was said that the person it represented would not live out the year.[41]

Telling ghost stories and watching horror films are common fixtures of Halloween parties. Episodes of television series and Halloween-themed specials (with the specials usually aimed at children) are commonly aired on or before Halloween, while new horror films are often released before Halloween to take advantage of the holiday.

Haunted attractions

Humorous tombstones in front of a house in California

Haunted attractions are entertainment venues designed to thrill and scare patrons. Most attractions are seasonal Halloween businesses that may include haunted houses, corn mazes, and hayrides,[166] and the level of sophistication of the effects has risen as the industry has grown.

The first recorded purpose-built haunted attraction was the Orton and Spooner Ghost House, which opened in 1915 in Liphook, England. This attraction actually most closely resembles a carnival fun house, powered by steam.[167] [168] The House still exists, in the Hollycombe Steam Collection.

It was during the 1930s, about the same time as trick-or-treating, that Halloween-themed haunted houses first began to appear in America. It was in the late 1950s that haunted houses as a major attraction began to appear, focusing first on California. Sponsored by the Children’s Health Home Junior Auxiliary, the San Mateo Haunted House opened in 1957. The San Bernardino Assistance League Haunted House opened in 1958. Home haunts began appearing across the country during 1962 and 1963. In 1964, the San Manteo Haunted House opened, as well as the Children’s Museum Haunted House in Indianapolis.[169]

The haunted house as an American cultural icon can be attributed to the opening of the Haunted Mansion in Disneylandon August 12, 1969.[170] Knott’s Berry Farm began hosting its own Halloween night attraction, Knott’s Scary Farm, which opened in 1973.[171] Evangelical Christians adopted a form of these attractions by opening one of the first “hell houses” in 1972.[172]

The first Halloween haunted house run by a nonprofit organization was produced in 1970 by the Sycamore-Deer Park Jaycees in Clifton, Ohio. It was cosponsored by WSAI, an AM radio station broadcasting out of Cincinnati, Ohio. It was last produced in 1982.[173] Other Jaycees followed suit with their own versions after the sucess of the Ohio house. The March of Dimes copyrighted a “Mini haunted house for the March of Dimes” in 1976 and began fundraising through their local chapters by conducting haunted houses soon after. Although they apparently quit supporting this type of event nationally sometime in the 1980s, some March of Dimes haunted houses have persisted until today.[174]

On the evening of May 11, 1984, in Jackson Township, New Jersey, the Haunted Castle (Six Flags Great Adventure)caught fire. As a result of the fire, eight teenagers perished.[175] The backlash to the tragedy was a tightening of regulations relating to safety, building codes and the frequency of inspections of attractions nationwide. The smaller venues, especially the nonprofit attractions, were unable to compete financially, and the better funded commercial enterprises filled the vacuum.[176][177] Facilities that were once able to avoid regulation because they were considered to be temporary installations now had to adhere to the stricter codes required of permanent attractions.[178][179][180]

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, theme parks entered the business seriously. Six Flags Fright Fest began in 1986 and Universal Studios Florida began Halloween Horror Nights in 1991. Knott’s Scary Farm experienced a surge in attendance in the 1990s as a result of America’s obsession with Halloween as a cultural event. Theme parks have played a major role in globalizing the holiday. Universal Studios Singapore and Universal Studios Japan both participate, while Disney now mounts Mickey’s Not-So-Scary Halloween Party events at its parks in Paris, Hong Kong and Tokyo, as well as in the United States.[181] The theme park haunts are by far the largest, both in scale and attendance.

Food

A jack-o’-lantern Halloween cakewith a witches hat

On All Hallows’ Eve, many Western Christian denominations encourage abstinence from meat, giving rise to a variety of vegetarian foods associated with this day.[182]

Because in the Northern Hemisphere Halloween comes in the wake of the yearly apple harvest, candy apples (known as toffee apples outside North America), caramel or taffy apples are common Halloween treats made by rolling whole apples in a sticky sugar syrup, sometimes followed by rolling them in nuts.

At one time, candy apples were commonly given to trick-or-treating children, but the practice rapidly waned in the wake of widespread rumors that some individuals were embedding items like pins and razor blades in the apples in the United States.[183]While there is evidence of such incidents,[184] relative to the degree of reporting of such cases, actual cases involving malicious acts are extremely rare and have never resulted in serious injury. Nonetheless, many parents assumed that such heinous practices were rampant because of the mass media. At the peak of the hysteria, some hospitals offered free X-rays of children’s Halloween hauls in order to find evidence of tampering. Virtually all of the few known candy poisoning incidents involved parents who poisoned their own children’s candy.[185]

One custom that persists in modern-day Ireland is the baking (or more often nowadays, the purchase) of a barmbrack (Irish: báirín breac), which is a light fruitcake, into which a plain ring, a coin, and other charms are placed before baking. It is said that those who get a ring will find their true love in the ensuing year. This is similar to the tradition of king cake at the festival of Epiphany.

List of foods associated with Halloween:

- Barmbrack (Ireland)

- Bonfire toffee (Great Britain)

- Candy apples/toffee apples (Great Britain and Ireland)

- Candy apples, Candy corn, candy pumpkins (North America)

- Monkey nuts (peanuts in their shells) (Ireland and Scotland)

- Caramel apples

- Caramel corn

- Colcannon (Ireland; see below)

- Halloween cake

- Novelty candy shaped like skulls, pumpkins, bats, worms, etc.

- Roasted pumpkin seeds

- Roasted sweet corn

- Soul cakes

Christian religious observances

The Vigil of All Hallows’ is being celebrated at an Episcopal Christian church on Hallowe’en.

On Hallowe’en (All Hallows’ Eve), in Poland, believers were once taught to prayout loud as they walk through the forests in order that the souls of the dead might find comfort; in Spain, Christian priests in tiny villages toll their church bells in order to remind their congregants to remember the dead on All Hallows’ Eve.[186]In Ireland, and among immigrants in Canada, a custom includes the Christian practice of abstinence, keeping All Hallows’ Eve as a meat-free day, and serving pancakes or colcannon instead.[187] In Mexico children make an altar to invite the return of the spirits of dead children (angelitos).[188]

The Christian Church traditionally observed Hallowe’en through a vigil. Worshippers prepared themselves for feasting on the following All Saints’ Daywith prayers and fasting.[189] This church service is known as the Vigil of All Hallows or the Vigil of All Saints;[190][191] an initiative known as Night of Lightseeks to further spread the Vigil of All Hallows throughout Christendom.[192][193]After the service, “suitable festivities and entertainments” often follow, as well as a visit to the graveyard or cemetery, where flowers and candles are often placed in preparation for All Hallows’ Day.[194][195] In Finland, because so many people visit the cemeteries on All Hallows’ Eve to light votive candles there, they “are known as valomeri, or seas of light”.[196]

Halloween Scripture Candy with gospel tract

Today, Christian attitudes towards Halloween are diverse. In the Anglican Church, some dioceses have chosen to emphasize the Christian traditions associated with All Hallow’s Eve.[197][198] Some of these practices include praying, fasting and attending worship services.[1][2][3]

O LORD our God, increase, we pray thee, and multiply upon us the gifts of thy grace: that we, who do prevent the glorious festival of all thy Saints, may of thee be enabled joyfully to follow them in all virtuous and godly living. Through Jesus Christ, Our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end. Amen. —Collect of the Vigil of All Saints, The Anglican Breviary[199]

Votive candles in the Halloween section of Walmart

Other Protestant Christians also celebrate All Hallows’ Eve as Reformation Day, a day to remember the Protestant Reformation, alongside All Hallow’s Eve or independently from it.[200][201] This is because Martin Luther is said to have nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg on All Hallows’ Eve.[202] Often, “Harvest Festivals” or “Reformation Festivals” are held on All Hallows’ Eve, in which children dress up as Bible characters or Reformers.[203] In addition to distributing candy to children who are trick-or-treating on Hallowe’en, many Christians also provide gospel tracts to them. One organization, the American Tract Society, stated that around 3 million gospel tracts are ordered from them alone for Hallowe’en celebrations.[204] Others order Halloween-themed Scripture Candy to pass out to children on this day.[205][206]

Some Christians feel concerned about the modern celebration of Halloween because they feel it trivializes – or celebrates – paganism, the occult, or other practices and cultural phenomena deemed incompatible with their beliefs.[207] Father Gabriele Amorth, an exorcist in Rome, has said, “if English and American children like to dress up as witches and devils on one night of the year that is not a problem. If it is just a game, there is no harm in that.”[208] In more recent years, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston has organized a “Saint Fest” on Halloween.[209]Similarly, many contemporary Protestant churches view Halloween as a fun event for children, holding events in their churches where children and their parents can dress up, play games, and get candy for free. To these Christians, Halloween holds no threat to the spiritual lives of children: being taught about death and mortality, and the ways of the Celtic ancestors actually being a valuable life lesson and a part of many of their parishioners’ heritage.[210] Christian minister Sam Portaro wrote that Halloween is about using “humor and ridicule to confront the power of death”.[211]

In the Roman Catholic Church, Halloween’s Christian connection is cited, and Halloween celebrations are common in Catholic parochial schools throughout North America and in Ireland.[212][better source needed] Many fundamentalist and evangelical churches use “Hell houses” and comic-style tracts in order to make use of Halloween’s popularity as an opportunity for evangelism.[213] Others consider Halloween to be completely incompatible with the Christian faith due to its putative origins in the Festival of the Dead celebration.[214] Indeed, even though Eastern Orthodox Christians observe All Hallows’ Day on the First Sunday after Pentecost. The Eastern Orthodox Church recommends the observance of Vespersor a Paraklesis on the Western observance of All Hallows’ Eve, out of the pastoral need to provide an alternative to popular celebrations.[215]

Analogous celebrations and perspectives

Judaism

According to Alfred J. Kolatch in the Second Jewish Book of Why, in Judaism, Halloween is not permitted by Jewish Halakha because it violates Leviticus 18:3, which forbids Jews from partaking in gentile customs. Many Jews observe Yizkor, which is equivalent to the observance of Allhallowtide in Christianity, as prayers are said for both “martyrs and for one’s own family”.[216] Nevertheless, many American Jews celebrate Halloween, disconnected from its Christian origins.[217] Reform Rabbi Jeffrey Goldwasser has said that “There is no religious reason why contemporary Jews should not celebrate Halloween” while Orthodox Rabbi Michael Broyde has argued against Jews observing the holiday.[218] Jews do have the Purim holiday, where the children dress up in costumes to celebrate.[219]

Islam

Sheikh Idris Palmer, author of A Brief Illustrated Guide to Understanding Islam, has argued that Muslims should not participate in Halloween, stating that “participation in Halloween is worse than participation in Christmas, Easter, … it is more sinful than congratulating the Christians for their prostration to the crucifix”.[220] Javed Memon, a Muslim writer, has disagreed, saying that his “daughter dressing up like a British telephone booth will not destroy her faith as a Muslim”.[221]

Hinduism

Most Hindus do not observe All Hallows’ Eve, instead they remember the dead during the festival of Pitru Paksha, during which Hindus pay homage to and perform a ceremony “to keep the souls of their ancestors at rest”. It is celebrated in the Hindu month of Bhadrapada, usually in mid-September.[222] The celebration of the Hindu festival Diwali sometimes conflicts with the date of Halloween; but some Hindus choose to participate in the popular customs of Halloween.[223]Other Hindus, such as Soumya Dasgupta, have opposed the celebration on the grounds that Western holidays like Halloween have “begun to adversely affect our indigenous festivals”.[224]

Neopaganism

There is no consistent rule or view on Halloween amongst those who describe themselves as Neopagans or Wiccans. Some Neopagans do not observe Halloween, but instead observe Samhain on 1 November,[225] some neopagans do enjoy Halloween festivities, stating that one can observe both “the solemnity of Samhain in addition to the fun of Halloween”. Some neopagans are opposed to the celebration of Hallowe’en, stating that it “trivializes Samhain”,[226] and “avoid Halloween, because of the interruptions from trick or treaters”.[227] The Manitoban writes that “Wiccans don’t officially celebrate Halloween, despite the fact that 31 Oct. will still have a star beside it in any good Wiccan’s day planner. Starting at sundown, Wiccans celebrate a holiday known as Samhain. Samhain actually comes from old Celtic traditions and is not exclusive to Neopagan religions like Wicca. While the traditions of this holiday originate in Celtic countries, modern day Wiccans don’t try to historically replicate Samhain celebrations. Some traditional Samhain rituals are still practised, but at its core, the period is treated as a time to celebrate darkness and the dead — a possible reason why Samhain can be confused with Halloween celebrations.”[225]

Around the world

A Halloween display in Saitama, Japan

The traditions and importance of Halloween vary greatly among countries that observe it. In Scotland and Ireland, traditional Halloween customs include children dressing up in costume going “guising”, holding parties, while other practices in Ireland include lighting bonfires, and having firework displays.[228][229] In Brittany children would play practical jokes by setting candles inside skulls in graveyards to frighten visitors.[230] Mass transatlantic immigration in the 19th century popularized Halloween in North America, and celebration in the United States and Canada has had a significant impact on how the event is observed in other nations. This larger North American influence, particularly in iconic and commercial elements, has extended to places such as Ecuador, Chile,[231]Australia,[232] New Zealand,[233] (most) continental Europe, Japan, and other parts of East Asia.[234] In the Philippines, during Halloween, Filipinos return to their hometowns and purchase candles and flowers,[235] in preparation for the following All Saints Day (Araw ng mga Patay) on 1 November and All Souls Day —though it falls on 2 November, most of them observe it on the day before.[236]In Mexico and Latin American in general, it is referred to as ” Día de los Muertos ” which translates in English to ” Day of the dead”. Most of the people from Latin America construct altars in their homes to honor their deceased relatives and they decorate them with flowers and candies and other offerings

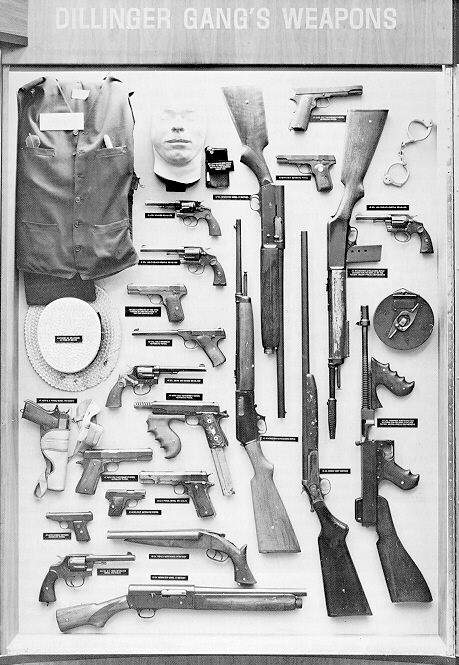

John Dillinger

One Really Bad Dude

One Really Bad Dude

Back in the Days of Real Gangsters of America. Mr. D was the King of the Publicity for these folks.

Here is his story:

John Herbert Dillinger (/dɪlɪndʒər/; June 22, 1903 – July 22, 1934) was an American gangster in the Depression-era United States. He operated with a group of men known as the Dillinger Gang or Terror Gang, which was accused of robbing 24 banks and four police stations, among other activities. Dillinger escaped from jail twice. He was also charged with, but never convicted of, the murder of an East Chicago, Indiana, police officer who shot Dillinger in his bullet-proof vest during a shootout, prompting him to return fire; despite his infamy, it was Dillinger’s only homicide charge.

He courted publicity and the media of his time ran exaggerated accounts of his bravado and colorful personality, styling him as a Robin Hood figure.[1] In response, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover developed a more sophisticated Bureau as a weapon against organized crime, using Dillinger and his gang as his campaign platform.[1]

After evading police in four states for almost a year, Dillinger was wounded and returned to his father’s home to recover. He returned to Chicago in July 1934 and met his end at the hands of police and federal agents who were informed of his whereabouts by Ana Cumpănaş (the owner of the brothel where Dillinger had sought refuge at the time). On July 22, 1934, the police and the Division of Investigation[2] closed in on the Biograph Theater. Federal agents, led by Melvin Purvis and Samuel P. Cowley, moved to arrest Dillinger as he exited the theater. He drew a Colt Model 1908 Vest Pocketand attempted to flee, but was killed. This was ruled as a justifiable homicide.[3][4]

Early life

Family and background[edit]

John Dillinger was born on June 22, 1903, in Indianapolis, Indiana,[5] the younger of two children born to John Wilson Dillinger (1864 –1943) and Mary Ellen “Mollie” Lancaster (1860–1907).[6]:10

According to some biographers, his German grandfather, Matthias Dillinger, emigrated to the United States in 1851 from Metz, in the region of Lorraine, then under French sovereignty.[7] Matthias Dillinger was born in Gisingen, near Dillingen in present-day Saarland. John Dillinger’s parents had married on August 23, 1887. Dillinger’s father was a grocer by trade and, reportedly, a harsh man.[6]:9 In an interview with reporters, Dillinger said that he was firm in his discipline and believed in the adage “spare the rod and spoil the child”.[6]:12

Dillinger’s older sister, Audrey, was born March 6, 1889. Their mother died in 1907 just before his fourth birthday.[6][8]Audrey married Emmett “Fred” Hancock that year and they had seven children together. She cared for her brother John for several years until their father remarried in 1912 to Elizabeth “Lizzie” Patel (1878–1933). They had three children, Hubert, born 1912, Doris M. (1918–2001) and Frances Dillinger (1922–2015).[8][9]

Reportedly, Dillinger initially disliked his stepmother, but he eventually came to fall in love with her. The two eventually began a relationship that lasted 3 years.[10]

Formative years and marriage[edit]

As a teenager, Dillinger was frequently in trouble with the law for fighting and petty theft; he was also noted for his “bewildering personality” and bullying of smaller children.[6]:14 He quit school to work in an Indianapolis machine shop. His father feared that the city was corrupting his son, prompting him to move the family to Mooresville, Indiana, in 1921.[6]:15Dillinger’s wild and rebellious behavior was unchanged, despite his new rural life. In 1922, he was arrested for auto theft, and his relationship with his father deteriorated.[6]:16–17

His troubles led him to enlist in the United States Navy, where he was a Fireman 3rd Class assigned aboard the battleship USS Utah,[11] but he deserted a few months later when his ship was docked in Boston. He was eventually dishonorably discharged.[6]:18–20

Dillinger then returned to Mooresville where he met Beryl Ethel Hovious.[12] The two were married on April 12, 1924. He attempted to settle down, but he had difficulty holding a job and preserving his marriage.[1]

Dillinger was unable to find a job and began planning a robbery with his friend Ed Singleton.[6]:22 The two robbed a local grocery store, stealing $50.[6]:26 While leaving the scene, the criminals were spotted by a minister who recognized the men and reported them to the police. The two men were arrested the next day. Singleton pleaded not guilty, but after Dillinger’s father (the local Mooresville Church deacon) discussed the matter with Morgan County prosecutor Omar O’Harrow, his father convinced Dillinger to confess to the crime and plead guilty without retaining a defense attorney.[6]:24Dillinger was convicted of assault and battery with intent to rob, and conspiracy to commit a felony. He expected a lenient probation sentence as a result of his father’s discussion with O’Harrow, but instead was sentenced to 10 to 20 years in prison for his crimes.[8] His father told reporters he regretted his advice and was appalled by the sentence. He pleaded with the judge to shorten the sentence, but with no success.[6]:25 (During the robbery, Dillinger had struck a victim on the head with a machine bolt wrapped in a cloth and had also carried a gun which, although it discharged, hit no one). En route to Mooresville to testify against Singleton, Dillinger briefly escaped his captors, but was apprehended within a few minutes.[6]:27 Singleton had a change of venue and was sentenced to a jail term of 2 to 14 years. He was killed on August 31, 1937, by a train when he passed out, drunk, on a railroad track.[13]

Prison time[edit]

Within Indiana Reformatory and Indiana State Prison, from 1924 to 1933, Dillinger began to become embroiled in a criminal lifestyle. Upon being admitted to the prison, he is quoted as saying, “I will be the meanest bastard you ever saw when I get out of here.”[6]:26 His physical examination upon being admitted to the prison showed that he had gonorrhea. The treatment for his condition was extremely painful.[6]:22 He became embittered against society because of his long prison sentence and befriended other criminals, such as seasoned bank robbers like Harry “Pete” Pierpont, Charles Makley, Russell Clark, and Homer Van Meter, who taught Dillinger how to be a successful criminal. The men planned heists that they would commit soon after they were released.[6]:32 Dillinger studied Herman Lamm‘s meticulous bank-robbing system and used it extensively throughout his criminal career.[citation needed]

His father launched a campaign to have him released and was able to get 188 signatures on a petition. Dillinger was paroled on May 10, 1933, after serving nine and a half years. Dillinger’s stepmother became sick just before he was released from the prison, and died before he arrived at her home.[6]:37 Released at the height of the Great Depression, Dillinger had little prospect of finding employment.[6]:35 He immediately returned to crime.[6]:39

On June 21, 1933, he robbed his first bank, taking $10,000 from the New Carlisle National Bank, which occupied the building at the southeast corner of Main Street and Jefferson (State Routes 235 and 571) in New Carlisle, Ohio.[14] On August 14, Dillinger robbed a bank in Bluffton, Ohio. Tracked by police from Dayton, Ohio, he was captured and later transferred to the Allen County Jail in Lima to be indicted in connection to the Bluffton robbery. After searching him before letting him into the prison, the police discovered a document which appeared to be a prison escape plan. They demanded Dillinger tell them what the document meant, but he refused.[8]

Dillinger had helped conceive a plan for the escape of Pierpont, Clark and six others he had met while in prison, most of whom worked in the prison laundry. Dillinger had friends smuggle guns into their cells, with which they escaped, four days after Dillinger’s capture. The group, known as “the First Dillinger Gang,” comprised Pete Pierpont, Russell Clark, Charles Makley, Ed Shouse, Harry Copeland, and John “Red” Hamilton, a member of the Herman Lamm Gang. Pierpont, Clark, and Makley arrived in Lima on October 12, where they impersonated Indiana State Police officers, claiming they had come to extradite Dillinger to Indiana. When the sheriff, Jess Sarber, asked for their credentials, Pierpont shot Sarber dead, then released Dillinger from his cell. The four men escaped back to Indiana, where they joined the rest of the gang.[8]

Bank robberies[edit]

Dillinger is known to have participated with The Dillinger Gang in twelve separate bank robberies, between June 21, 1933 and June 30, 1934.[citation needed]

Relationship with Evelyn Frechette[edit]

Evelyn “Billie” Frechette met John Dillinger in October 1933, and they began a relationship on November 20. After Dillinger’s death, Billie was offered money for her story and eventually penned a memoir for the Chicago Herald and Examiner in August 1934.[15]

Escape from Crown Point, Indiana[edit]

Dillinger was finally caught by Matthew “Matt” Leach, the chief of the Indiana State Police, and imprisoned within the Crown Point jail sometime after committing a robbery at a bank located in East Chicago on January 15, 1934. The local police boasted to area newspapers that the jail was escape-proof and posted extra guards to make sure. What happened on the day of Dillinger’s escape on March 3 is still open to debate. Deputy Ernest Blunk claimed that Dillinger had escaped using a real pistol, but FBI files make clear that Dillinger carved a fake pistol from a potato. Sam Cahoon, a trustee that Dillinger first took hostage in the jail, believed that Dillinger had carved the gun with a razor and some shelving in his cell. However, according to an unpublished interview with Dillinger’s attorney, Louis Piquett and his investigator, Art O’Leary, O’Leary claimed to have sneaked the gun in himself.[16]

On March 16, Herbert Youngblood, a fellow escapee from Crown Point, was shot dead by three police officers in Port Huron, Michigan. Deputy Sheriff Charles Cavanaugh was fatally wounded in the battle and died a few hours later. Before he died, Youngblood told the officers that Dillinger was in the neighborhood of Port Huron, and immediately officers began a search for the escaped man, but no trace of him was found. An Indiana newspaper reported that Youngblood later retracted the story and said he did not know where Dillinger was at that time, as he had parted with him soon after their escape.[17]

Dillinger was indicted by a local grand jury, and the Bureau of Investigation (a precursor of the Federal Bureau of Investigation)[2] organized a nationwide manhunt for him.[18] After escaping from Crown Point, Dillinger reunited with his girlfriend, Evelyn Frechette, just hours after his escape at her half-sister Patsy’s Chicago apartment, where she was also staying (3512 North Halsted).

According to Billie’s trial testimony, Dillinger stayed with her there for “almost two weeks,” but the two actually had traveled to the Twin Cities and moved into the Santa Monica Apartments, Unit 106, 3252 South Girard Avenue, Minneapolis, on March 4 (moving out on March 19)[19][20] and met up with Hamilton (who had been recovering for the past month from his gunshot wounds in the East Chicago robbery), and mustered a new gang, and the two joined Baby Face Nelson‘s gang, composed of Homer Van Meter, Tommy Carroll and Eddie Green.[clarification needed]

Three days after Dillinger’s escape from Crown Point, the second Dillinger Gang robbed a bank in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. A week later they robbed First National Bank in Mason City, Iowa.[citation needed]

Lincoln Court shootout[edit]

|

|

This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (June 2015)

|

Dillinger and Billie eventually moved into apartment 303 of the Lincoln Court Apartments, 93-95 South Lexington Avenue (now Lexington Parkway South) in St. Paul, Minnesota, on Tuesday, March 20, using the aliases “Mr. & Mrs. Carl T. Hellman”. The three-story apartment complex (still in operation)[21] had 32 apartments — 10 units on each floor, plus two basement units.[22][23]

Daisy Coffey, the landlord/owner, would testify at Frechette’s trial that she spent most evenings during the Hellmans’ stay furnishing apartment 310, which enabled her to observe what was happening in apartment 303 directly across the courtyard. On March 30, Coffey went to the FBI’s St. Paul field office to file a report, including information about the couple’s new Hudson sedan parked in the garage behind the apartments. The building was placed under surveillance by two agents, Rufus Coulter and Rusty Nalls, that night, but they saw nothing unusual, mainly due to the blinds being drawn.[24]

The next morning at approximately 10:15, Nalls circled around the block looking for the Hudson, but observed nothing. He parked, first on Lincoln (the north side of the apartments), then on the west side of Lexington, at the northwest corner of Lexington and Lincoln, and remained in his car while watching Coulter and St. Paul Police detective Henry Cummings, pull up, park, and enter the building.[25] Ten minutes later, by Nalls’s estimate, Van Meter parked a green Ford coupe on the north side of the apartment building.[26]

Meanwhile, Coulter and Cummings knocked on the door of apartment 303. Frechette answered, opening the door two to three inches. She said she was not dressed and to come back. Coulter told her they would wait. After waiting two to three minutes, Coulter went to the basement apartment of the caretakers, Louis and Margaret Meidlinger, and asked to use the phone to call the bureau. He quickly returned to Cummings, and the two of them waited for Frechette to open the door. Van Meter then appeared in the hall and asked Coulter if his name was Johnson. Coulter said it was not, and as Van Meter passed on to the landing of the third floor, Coulter asked him for a name. Van Meter replied, “I am a soap salesman.” Asked where his samples were, Van Meter said they were in his car. Coulter asked if he had any credentials. Van Meter said “no,” and continued down the stairs. Coulter waited 10 to 20 seconds, then followed Van Meter. As Coulter got to the lobby on the ground floor, Van Meter opened fire on him.[27] Coulter hastily fled outside, chased by Van Meter. Eventually, Van Meter ran back into the front entrance.

Recognizing Van Meter, Nalls pointed out the Ford to Coulter and told him to disable it. Coulter shot out the rear left tire. While Coulter stayed with Van Meter’s Ford, Nalls went to the corner drugstore and called first the local police, then the bureau’s St. Paul office, but could not get through because both lines were busy.[28][29] Van Meter, meanwhile, escaped by hopping on a passing coal truck.[30]

Frechette, in her harboring trial testimony, said that she told Dillinger that the police had showed up after speaking to Cummings. Upon hearing Van Meter firing at Coulter, Dillinger opened fire through the door with a Thompson submachine gun, sending Cummings scrambling for cover. Dillinger then stepped out and fired another burst at Cummings. Cummings shot back with a revolver, but quickly ran out of ammunition. He hit Dillinger in the left calf with one of his five shots. He then hastily retreated down the stairs to the front entrance.[31] Once Cummings retreated, Dillinger and Frechette hurried down the stairs, exited through the back door and drove away in the Hudson.

The couple drove to the apartment of Eddie Green at 3300 South Fremont in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Green called his associate Dr. Clayton E. May at his office in Minneapolis, 712 Masonic Temple (still extant). With Green, his wife Beth, and Frechette following in Green’s car, Dr. May drove Dillinger to 1835 Park Avenue, Minneapolis, to the apartment of Augusta Salt, who had been providing nursing services and a bed for May’s illicit patients for several years, patients he could not risk seeing at his regular office. May treated Dillinger’s wound with antiseptics. Eddie Green visited Dillinger on Monday, April 2, just hours before Green would be mortally wounded by the FBI in St. Paul. Dillinger convalesced at Dr. May’s for five days, until Wednesday, April 4. Dr. May was promised $500 for his services, but received nothing.

Return to Mooresville

After leaving Minneapolis, Dillinger and Billie traveled to Mooresville to visit Dillinger’s father. Friday, April 6 was spent contacting family members, particularly his half-brother Hubert Dillinger. On April 6, Hubert and Dillinger left Mooresville at about 8:00 p.m. and proceeded to Leipsic, Ohio (approximately 210 miles away), to see Joseph and Lena Pierpont, Harry’s parents. The Pierponts were not home, so the two headed back to Mooresville around midnight.[34]

On April 7 at approximately 3:30 a.m., they rammed a car driven by Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Manning near Noblesville, Indiana, after Hubert fell asleep behind the wheel. They crashed through a farm fence and about 200 feet into the woods. Both men made it back to the Mooresville farm. Swarms of police showed up at the accident scene within hours. Found in the car were maps, a machine gun magazine, a length of rope, and a bullwhip. According to Hubert, his brother planned to pay a visit with the bullwhip to his former one-armed “shyster” lawyer at Crown Point, Joseph Ryan, who had run off with his retainer after being replaced by Louis Piquett.[citation needed]

At about 10:30 a.m. on April 7, Billie, Hubert and Hubert’s wife purchased a black four-door Ford V8, registering it in the name of Mrs. Fred Penfield (Billie Frechette). At 2:30 p.m., Billie and Hubert picked up the V8 and returned to Mooresville.[citation needed]

On Sunday, April 8, the Dillingers enjoyed a family picnic while the FBI had the farm under surveillance nearby.[34] Later in the afternoon, suspecting they were being watched (agents J. L. Geraghty and T. J. Donegan were cruising in the vicinity in their car), the group left in separate cars. Billie drove the new Ford V8, with two of Dillinger’s nieces, Mary Hancock in the front seat and Alberta Hancock in the back. Dillinger was on the floor of the car. He was later seen, but not recognized, by Donegan and Geraghty. Eventually, Norman, driving the V8, proceeded with Dillinger and Billie to Chicago, where they separated from Norman.[34]

The following afternoon, Monday, April 9, Dillinger had an appointment at a tavern at 416 North State Street. Sensing trouble, Billie went in first. She was promptly arrested by agents, but refused to reveal Dillinger’s whereabouts. Dillinger was waiting in his car outside the tavern and then drove off unnoticed.[35] The two would never see each other again.[citation needed]

Dillinger reportedly became despondent after Billie was arrested. The other gang members tried to talk to him out of rescuing her, but Van Meter knew where they could find bulletproof vests. That Friday morning, late at night, Dillinger and Van Meter took Warsaw, Indiana police officer Judd Pittenger hostage. They marched him at gunpoint to the police station, where they stole several more guns and bulletproof vests. After separating, Dillinger picked up Hamilton, who was recovering from the Mason City robbery. The two then traveled to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where they visited Hamilton’s sister Anna Steve.[citation needed]

Hiding in Chicago[edit]

By July 1934, Dillinger had dropped completely out of sight, and the federal agents had no solid leads to follow. He had, in fact, drifted into Chicago where he went under the alias of Jimmy Lawrence, a petty criminal from Wisconsin who bore a close resemblance to Dillinger. Working as a clerk, Dillinger found that, in a large metropolis like Chicago, he was able to lead an anonymous existence for a while. What he did not realize was that the center of the federal agents’ dragnet happened to be Chicago. When the authorities found Dillinger’s blood-spattered getaway car on a Chicago side street, they were positive that he was in the city.[8]

Dillinger had always been a fan of the Chicago Cubs, and instead of lying low like many criminals on the run, he attended Cubs games at Wrigley Field during June and July.[36] He’s known to have been at Wrigley on Friday, June 8, only to watch his beloved Cubs lose to Cincinnati 4-3. Also in attendance at the game were Dillinger’s lawyer, Louis Piquett, and Captain John Stege of the Dillinger Squad.

Plastic surgery

According to Art O’Leary, as early as March 1934, Dillinger expressed an interest in plastic surgery and had asked O’Leary to check with Piquett on such matters. At the end of April, Piquett paid a visit to his old friend Dr. Wilhelm Loeser. Loeser had practiced in Chicago for 27 years before being convicted under the Harrison Narcotic Act in 1931. He was sentenced to three years at Leavenworth, but was paroled early on December 7, 1932, with Piquett’s help.[citation needed] He later testified that he performed facial surgery on himself and obliterated the fingerprint impressions on the tips of his fingers by the application of a caustic soda preparation. Piquett said Dillinger would have to pay $5,000 for the plastic surgery: $4,400 split between Piquett, Loeser and O’Leary, and $600 to Dr. Harold Cassidy, who would administer the anaesthetic. The procedure would take place at the home of Piquett’s longtime friend, 67-year-old James Probasco, at the end of May.[citation needed]

On May 28, Loeser was picked up at his home at 7:30 p.m. by O’Leary and Cassidy. The three of them then drove to Probasco’s place. Dillinger chose to have a general anaesthetic. Loeser later testified:

I asked him what work he wanted done. He wanted two warts (moles) removed on the right lower forehead between the eyes and one at the left angle, outer angle of the left eye; wanted a depression of the nose filled in; a scar; a large one to the left of the median line of the upper lip excised, wanted his dimples removed and wanted the angle of the mouth drawn up. He didn’t say anything about the fingers that day to me.[38]

Cassidy administered an overdose of ether, which caused Dillinger to suffocate. He began to turn blue and stopped breathing. Loeser pulled Dillinger’s tongue out of his mouth with a pair of forceps, and at the same time forcing both elbows into his ribs. Dillinger gasped and resumed breathing. The procedure continued with only a local anaesthetic. Loeser removed several moles on Dillinger’s forehead, made an incision in his nose and an incision in his chin and tied back both cheeks.[citation needed]

Loeser met with Piquett again on Saturday, June 2, with Piquett saying that more work was needed on Dillinger and that Van Meter now wanted the same work done to him. Also, both now wanted work done on their fingertips. The price for the fingerprint procedure would be $500 per hand or $100 a finger. Loeser used a mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acid—commonly known as aqua regia.[39][page needed]

Loeser met O’Leary the following night at Clark and Wright at 8:30, and they once again drove to Probasco’s. Present this evening were Dillinger, Van Meter, Probasco, Piquett, Cassidy, and Peggy Doyle, Probasco’s girlfriend. Loeser testified that he worked for only about 30 minutes before O’Leary and Piquett had left.

Loeser testified:

Cassidy and I worked on Dillinger and Van Meter simultaneously on June 3. While the work was being done, Dillinger and Van Meter changed off. The work that could be done while the patient was sitting up, that patient was in the sitting-room. The work that had to be done while the man was lying down, that patient was on the couch in the bedroom. They were changed back and forth according to the work to be done. The hands were sterilized, made aseptic with antiseptics, thoroughly washed with soap and water and used sterile gauze afterwards to keep them clean. Next, cutting instrument, knife was used to expose the lower skin…in other words, take off the epidermis and expose the derma, then alternately the acid and the alkaloid was applied as was necessary to produce the desired results.[40]

Minor work was done two nights later, Tuesday, June 5. Loeser made some small corrections first on Van Meter, then Dillinger. Loeser stated:

A man came in before I left, who I found out later was Baby Face Nelson. He came in with a drum of machine gun bullets under his arm, threw them on the bed or the couch in the bedroom, and started to talk to Van Meter. The two then motioned for Dillinger to come over and the three went back into the kitchen.

Peggy Doyle later told agents:

Dillinger and Van Meter resided at Probasco’s home until the last week of June 1934; that on some occasions they would be away for a day or two, sometimes leaving separately, and on other occasions together; that at this time Van Meter usually parked his car in the rear of Probasco’s residence outside the back fence; that she gathered that Dillinger was keeping company with a young woman who lived on the north side of Chicago, inasmuch as he would state upon leaving Probasco’s home that he was going in the direction of Diversey Boulevard; that Van Meter apparently was not acquainted with Dillinger’s friend, and she heard him warning Dillinger to be careful about striking up acquaintances with girls he knew nothing about; that Dillinger and Van Meter usually kept a machine gun in an open case under the piano in the parlor; that they also kept a shotgun under the parlor table.[41]

O’Leary stated that Dillinger expressed dissatisfaction with the facial work that Loeser had performed on him. O’Leary said that, on another occasion, “that Probasco told him, ‘the son of a bitch has gone out for one of his walks’; that he did not know when he would return; that Probasco raved about the craziness of Dillinger, stating that he was always going for walks and was likely to cause the authorities to locate the place where he was staying; that Probasco stated frankly on this occasion that he was afraid to have the man around.”[citation needed]

Agents arrested Loeser at 1127 South Harvey, Oak Park, Illinois, on Tuesday, July 24. O’Leary returned from a family fishing trip on July 24, the day of Loeser’s arrest, and had read in the newspapers that the Department of Justice was looking for two doctors and another man in connection with some plastic work that was done on Dillinger. O’Leary left Chicago immediately, but returned two weeks later, learned that Loeser and others had been arrested, phoned Piquett, who assured him everything was all right, then left again. He returned from St. Louis on August 25 and was promptly taken into custody.[42]

On Friday, July 27, Jimmy Probasco jumped or “accidentally” fell to his death from the 19th floor of the Bankers’ Building in Chicago while in custody.[citation needed]

On Thursday, August 23, Homer Van Meter was shot and killed in a dead-end alley in St. Paul by Tom Brown, former St. Paul Chief of Police, and then-current chief Frank Cullen.[citation needed]

Polly Hamilton, Dillinger’s last girlfriend[edit]

Rita “Polly” Hamilton was a teenage runaway from Fargo, North Dakota.[6] She met Ana Ivanova Akalieva- Ana Cumpănaş(aka Ana Sage) in Gary, Indiana, and worked periodically as a prostitute (in Anna’s brothel) until marrying Gary police officer Roy O. Keele in 1929.[6] They later divorced in March 1933.[6]

In the summer of 1934, the now twenty-six-year-old[1] Hamilton was a waitress in Chicago at the S&S Sandwich Shop located at 1209 ½ Wilson Avenue. She had remained friends with Sage and was sharing living space with Sage and Sage’s twenty-four-year-old son, Steve, at 2858 Clark Street.[6]

Dillinger and Hamilton, a Billie Frechette look-a-like,[1][6] met in June 1934 at the Barrel of Fun night club located at 4541 Wilson Avenue. Dillinger introduced himself as Jimmy Lawrence and said he was a clerk at the Board of Trade.[6] They dated until Dillinger’s death at the Biograph Theater in July 1934.[1][6]

Informant betrays Dillinger[edit]

Division of Investigations chief J. Edgar Hoover created a special task force headquartered in Chicago to locate Dillinger. On July 21, Ana Cumpănaș (a/k/a Anna Sage), a madam from a brothel in Gary, Indiana, also known as “The Woman in Red” contacted the FBI. She was a Romanian immigrant threatened with deportation for “low moral character”[43] and offered agents information on Dillinger in exchange for their help in preventing her deportation. The FBI agreed to her terms, but she was later deported nonetheless. Cumpănaş revealed that Dillinger was spending his time with another prostitute, Polly Hamilton, and that she and the couple would be going to see a movie together on the following day. She agreed to wear an orange dress,[44] so police could easily identify her. She was unsure which of two theaters they would be attending, the Biograph or the Marbro.[8] On December 15, 1934, pardons were issued by Indiana Governor Harry G. Leslie for the offenses of which Anna Sage was convicted.[45]

Sage stated that on Sunday afternoon, July 22, Dillinger asked her if she wanted to go to the show with them, he and Polly.