Category: I am so grateful!!

The Navy SEAL Who Went to Ukraine Because He Couldn’t Stop Fighting

Daniel Swift was in his element waging America’s war on terror from Afghanistan to Yemen. After his marriage failed back home, he found a new purpose: killing Russians.

by By Ian Lovett and Brett Forrest

Daniel Swift’s nerves were shot. By the start of 2019, his Navy SEAL colleagues said, he was hardly eating or sleeping.

He had separated from his wife. A court had barred him from seeing his four children, and he was facing legal charges for false imprisonment and domestic battery.

Mr. Swift told fellow SEALs in San Diego, where he was based, that he was planning to go to Africa to fight wildlife poachers. They brushed off the comment, convinced that Mr. Swift, a soldier’s soldier, would never abandon his post.

A week later, he disappeared. Navy investigators searched for him, but Mr. Swift was always a step ahead.

He resurfaced in March of last year when he slipped into a group messaging chat of current and former SEALs. He was now fighting Russians in Ukraine, he texted. He petitioned the group for supplies, and later invited members to join him on the front lines. None did. Some advised him to come home. Others marveled as word of his exploits spread.

Mr. Swift was among thousands of young men who flooded to Kyiv from the West, including American veterans of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Many said they were drawn to the cause of a democratic country resisting a larger autocratic one.

But there was another side to Mr. Swift’s quest, as revealed in interviews with his colleagues and a memoir he published online under a pseudonym. Mr. Swift was part of a large group who spent years fighting America’s war on terror and have struggled to settle back into civilian life.

The military has acknowledged the impact on servicemembers and their families, particularly special forces, who suffered the outsized casualties during the later years of the U.S. war in Afghanistan.

Long deployments have pushed up divorce rates, while suicides among special forces spiked to the highest in the military. The government has launched programs to help lessen the psychological burden on spouses as well as troops.

Daniel Glenn, a psychologist who works with veterans at the University of California, Los Angeles, said many tell him that the U.S. military does a great job preparing them to go to war, but not to return from it.

“They’ve been in some of the most intense, dangerous, awful situations. They’re really good at that,” he said. “Comparatively, back in the civilian world, everything feels mundane. It’s hard to have anything that feels like a rush or makes you feel alive.”

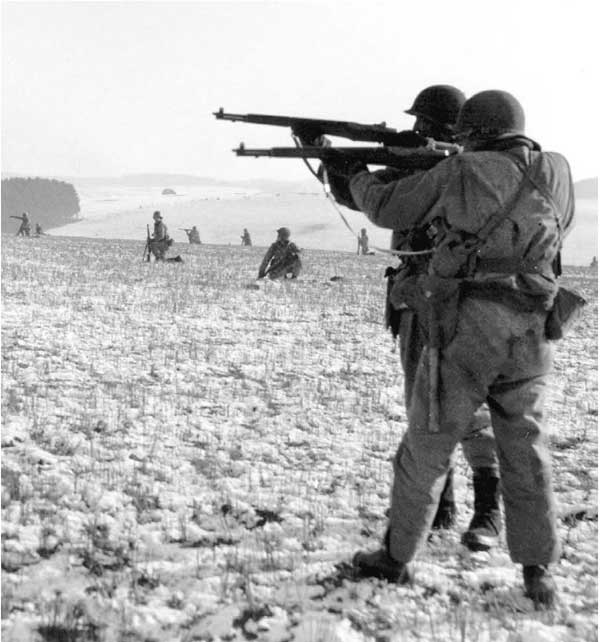

Daniel Swift serving in Severodonetsk, Ukraine.

Many of the men who fought with Mr. Swift said this feeling was part of what drew them to Ukraine.

“A lot of people won’t admit it, but lots of people are here because war is fun,” said a 43-year-old U.S. Army veteran. Civilian life, he added, didn’t offer the same camaraderie or sense of purpose: “War is easy in many ways. Your mission is crystal clear. You’re here to take the enemy out.”

‘Viet Dan’

Mr. Swift had wanted to be a Navy SEAL since childhood. After graduating from high school in rural Oregon in 2005, he married his high-school sweetheart and enlisted in the Navy.

Two years later, he enrolled in the SEALs selection program, a grueling process highlighted by “Hell Week,” when candidates train physically for more than 20 hours a day, run more than 200 miles and sleep for about four hours total.

The vast majority of candidates wash out. Mr. Swift, just 20 years old, made it. Soon after, his wife gave birth to their first child.

A teetotaler, Mr. Swift sometimes drove fellow SEALs on bar crawls, though he often stayed in and studied tactics in military manuals.

On deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, he won a reputation for dependability, a rare Legion of Merit award and a nickname, “Viet Dan,” inspired by his fondness for action.

“Tough kid, humble, quiet, and a little bit crazy,” said a SEAL who was the third in command of Mr. Swift’s first platoon.

In 2013, when his wife was pregnant with their fourth child, Mr. Swift decided to quit. “I thought maybe God was trying to tell me to settle down and be a family man,” he wrote in his memoir, which he self-published in 2020.

He joined the Washington state police and reveled in time off with his kids, exploring logging roads through the woods, cooking hot dogs and shooting guns.

The new job didn’t suit him, though. Police officers were rewarded for giving out tickets rather than helping people, he wrote in his book. Sitting in his cruiser scanning for speeders, Mr. Swift texted friends in the SEALs and told them he missed life among them, according to Navy comrades.

In 2015, a friend from the SEALs died, and Mr. Swift decided to re-enlist as a fight with Islamic State beckoned. “I wanted my piece of the pie,” he wrote.

In Iraq again, Mr. Swift took on Islamic State militants in city streets. Later, he deployed to Yemen.

Navy SEAL candidates train during ‘Hell Week.’ PHOTO: PETTY OFFICER 1ST CLASS ABE MCNATT/U.S. NAVY

Most candidates wash out of the SEALs selection program. PHOTO: PETTY OFFICER 1ST CLASS ABE MCNATT/U.S. NAVY

The overseas missions took a toll on his marriage. In October 2018, shortly after Mr. Swift returned from seven months in Yemen, his relationship with his wife collapsed.

In court documents, Maegan Swift said he’d returned home angry, prone to yelling at her. He disputed this account in his book, but both agreed that one night when they were arguing at home, she threatened to call the police if he prevented her from leaving with the kids.

Mr. Swift went to the bedroom and returned with a pistol.

He said in the book that it was unloaded and that he told her: “See what happens when the cops try and take my children from me.”

Ms. Swift moved the children to her sister’s house while Mr. Swift was traveling. When he returned, a scuffle ensued as he tried to put his younger daughter in his car and Ms. Swift and her sister tried to stop him. Mr. Swift said he was fending off the women as they attacked him; they said he choked Ms. Swift’s sister. The police arrived and arrested him.

Ms. Swift declined to comment for this article.

A Navy psychologist said Mr. Swift had adjustment disorder, a term for difficulty re-entering civilian life, Mr. Swift wrote in his memoir. He dismissed the diagnosis.

Mr. Swift was charged in state court with false imprisonment, child endangerment and domestic battery, which threatened his military career. If convicted of a felony, Mr. Swift would lose his right to carry a gun, and this prospect shook him, according to SEALs who knew him. Being a warrior was nearly all he’d known.

Most of all, he worried about losing his kids, the oldest of whom was the oldest of whom was 11.

Mr. Swift wrote that while the U.S. government has helped veterans cope with war trauma, “what we don’t seem to care about is when they return home to things they’ve been fighting for, only to have them ripped away.”

“I have been face to face with death multiple times, and it has never been more traumatic than having my children taken away,” he wrote.

In the early months of 2019, Mr. Swift disappeared. His passport pinged at immigration control in Mexico, then in Germany, a former SEAL colleague said.

Mr. Swift tried to join the French Foreign Legion, according to another SEAL colleague, but was rejected because the recruiters worried his kids could be a distraction. He ended up in Thailand where he fought kickboxing matches and taught English.

He wrote his memoir, he said, to explain himself to his children. “If you ever want to talk to me just make a Facebook page,” he wrote, addressing his kids. “I look.”

He titled the book “The Fall of a Man.”

No retreat

After Russia invaded Ukraine in February of last year, news reports of the war’s child victims reminded Mr. Swift of his own children and stirred him to action, he later told friends.

He entered Ukraine in early March and joined a platoon running missions behind enemy lines near Kyiv, according to soldiers who fought with him there.

During his first operations, he taped body armor to his chest under a white Fruit of the Loom T-shirt because he arrived without a vest to hold bulletproof plates. His teammates called it the “Dan special.”

Conducting reconnaissance and hunting armored vehicles with a Javelin antitank missile, he soon developed a reputation as highly skilled, methodical and most comfortable in the middle of a firefight, according to men who fought with him.

Adam Thiemann, a former U.S. Army Ranger, recalled one mission, where he and Mr. Swift set off with five others to ambush a Russian barrack. Outside the compound, they surprised a handful of uniformed Russian soldiers and quickly killed them. The Ukrainian commander ordered a retreat. Mr. Swift, who’d been quiet up to that point, was incredulous.

“Retreat?” Mr. Swift said, according to Mr. Thiemann and another team member. “We didn’t even get shot at.”

When Russian troops pulled back from Kyiv at the end of March, many foreign fighters went home, feeling they’d helped fend off the existential threat to Ukraine. Mr. Swift stayed.

His foreign legion team—a unit of Ukraine’s military intelligence, made up of about 20 foreigners and a Ukrainian commander—was dispatched to the city of Mykolaiv in the country’s south.

There, Mr. Swift led the squad on aquatic missions, often using inflatable boats to travel across open sea at night to target Russian positions, according to several soldiers in his unit.

During down time, teammates said, he was quiet and uncommonly disciplined. He didn’t drink or smoke, and worked out obsessively. Even near the front, he’d go out for long solo runs.

Men fighting with Mr. Swift in Ukraine said he would accompany them for shawarma in Mykolaiv, walking around shirtless in jeans and sandals and getting waitresses’ phone numbers. In photos, he rarely smiled; he was more likely to crack a joke during missions, they said.

He told only a few comrades about his life outside the military.

One teammate, a 29-year-old American who goes by the call sign Tex, said Mr. Swift confided in him about his troubles at home.

“He loved his kids,” Tex said. “A lot of things didn’t bother Dan. But the thought of his kids maybe being told who he was and not actually knowing him, that worried him.”

Ukrainian soldiers in the eastern city of Bakhmut in January. PHOTO: EMANUELE SATOLLI FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

In early June, the team headed to the eastern city of Severodonetsk, which the Russians were flattening with artillery.

The group had earned a reputation for taking on missions that others turned down. As the situation in Severodonetsk grew worse, Mr. Swift joked that if they were surrounded, at least they could shoot in every direction.

On its last trip into the city, the team tried to hit a building where they believed about 10 Russians were hiding. As soon as they fired the first rocket, however, they found themselves under heavy assault. Dozens of Russians were in the building. Mr. Swift ended up trapped in a corner, trading machine-gun fire with a Russian.

The legion team’s Ukrainian commander, Oleksiy Chubashev, was shot through the neck.

With a Russian tank approaching, Mr. Swift laid down covering fire to free a group of pinned-down comrades, who put Capt. Chubashev on a stretcher and carried him out the back of the building.

Mr. Swift joined them outside to help carry the stretcher. A video seen by The Wall Street Journal shows them hauling the body through the city in daylight, without cover, while artillery shells whistle and crash around them.

After about a half a mile in the June heat, an exhausted young soldier dropped his corner of the stretcher.

“Dan just tore into him,” a member of the team from Minnesota recalled. “He never yells. But he screamed, like, ‘What are you saving your energy for?’ ”

Capt. Chubashev died before making it back to base.

The next morning, Mr. Swift sat down beside several teammates who were drinking coffee. He said he was thinking about calling his children.

The men were shocked. They didn’t know he had kids.

Soon after, Ukrainian forces started to retreat from Severodonetsk. Several of the men on Mr. Swift’s team decided they’d had enough. They went home.

‘I’ll walk out’

Mr. Swift, by contrast, began setting up for life in Ukraine. He was looking for an apartment in Kyiv and sorted out a Ukrainian visa for a Thai woman he’d met when he was living there. He spoke of establishing an academy in Ukraine after the war to teach military tactics.

He returned to Mykolaiv, where he again led aquatic missions into Russian-held territory.

In August, Mr. Swift led an attack on a Russian-held village across the Inhulets River. Working with Ukrainian special forces, the team forced the Russians to retreat, calling in a strike on a house full of enemy soldiers and taking seven prisoners.

But they ended up sheltering in a basement under Russian artillery fire. Mr. Swift called the unit’s new Ukrainian commander, asking to pull back, according to team members. The commander said no.

Mr. Swift pulled the team out anyway. In the middle of the night, he and the team medic swam upriver to retrieve a half-inflated boat to bring their comrades and gear back across to Ukrainian-held territory. When they got back to the base, Mr. Swift quit and moved to another foreign legion team.

A spokesman for Ukraine’s foreign legion declined to comment.

By the new year, Ukraine’s hold on Bakhmut, in the eastern Donetsk region, was tenuous. Mr. Swift’s unit, dispatched there, found Ukrainian troops scattered in basements around the city sheltering from withering Russian artillery fire.

“I’m just here in the basement,” Mr. Swift said in a phone call with a former Green Beret, who’d fought with him earlier in the war. “Trying to plan missions that are not going to get us killed.”

Mr. Swift was scheduled to leave Bakhmut later in January and planned to meet the Thai woman in Romania and bring her to Kyiv.

On the night of Jan. 17, Mr. Swift led a small team of Western fighters into a cluster of homes and began clearing them of fighters from the Russian paramilitary group Wagner, according to Mr. Swift’s unit commander. As Mr. Swift led his squad between buildings, a Russian soldier fired a rocket-propelled grenade.

A projectile, either shrapnel or a bullet, penetrated Mr. Swift’s helmet and lodged in his brain.

His commander found Mr. Swift lying prone, yet coherent. As the unit hurried to evacuate, Mr. Swift fought to remain lucid and asked for help getting to his feet. “I’ll walk out,” he said.

He lost consciousness and died three days later at a trauma center in Dnipro, a nearby regional capital. He was 35 years old.

A memorial service for Daniel Swift in Lviv, Ukraine. PHOTO: STANISLAV IVANOV/GLOBAL IMAGES UKRAINE/GETTY IMAGES

Mr. Swift died while still a SEAL, though AWOL, in a war to which the U.S. hasn’t committed troops. This has complicated his family’s effort to collect benefits from Washington.

A Navy spokesman said Mr. Swift was considered to be an active deserter at the time of his death, and that “we cannot speculate as to why the former Sailor was in Ukraine.” The Pentagon has yet to make a ruling on the family’s petition.

On Feb. 11, several SEALs attended Mr. Swift’s funeral in Oregon. In a video viewed by the Journal, one by one they punched metal SEAL pins into the surface of his casket, a SEAL ritual to the fallen.

Nikita Nikolaienko contributed to this article.

My son and I once visited with a man named Mr. Powell. At the time, he was 89 years old. His rural home was meticulously maintained and sported a spotless American flag snapping on a pole set in concrete in his front yard.

Mr. Powell hit Omaha Beach at around 1430 hours on D-Day. By that time, he said most of the German infantry was obliterated, but the pillboxes were still active. Powell explained that everybody who stopped on the beach died, while most of those that ran across and pushed inland lived. It took him five days to reach St. Lô, at which point General Patton took over. Powell revered Patton and spent the rest of the war with his Third Army.

Powell trained as a paratrooper and made his five jumps. For those who have done time at Fort Benning, he was there when they erected the jump towers. I hadn’t realized they were that old. He broke his collarbone and was subsequently assigned to a leg infantry unit. As a soldier, he made $21 a month, which he claimed twice as much money for half as much work compared to what he made before in south Mississippi.

During the Depression, he lived off of hickory nuts and opossums. He said opossum didn’t taste very good, but “You’d be surprised what you’ll eat when you’re hungry.”

Needless to say, Powell was a bad man in his prime. He was a Godly man, but Hitler started it, and Powell said he was determined to finish it.

Powell had one good buddy who always went out with him when the need arose. He quietly explained that “Them kraut sentries never stood a chance against the two of us.” And that they were very comfortable operating just the two of them alone in the dark with a knife. Apparently, they got fairly good at it.

Powell didn’t have much use for the Schutzstaffel (SS). He called them “Those Gestapo men.” I got the impression SS troops had a bit of a challenge successfully surrendering to Powell and his guys. He got tearful when discussing his wife’s stroke. By contrast, he loved talking about killing Germans.

At one point, his squad was assigned to secure Orly airport in Paris. After a brief firefight, the Germans surrendered. Powell said that the Germans were bad to leave a couple of guys back to shoot the GIs when they were processing prisoners. He and his patrolling buddy laid low and, sure enough, soon spotted a pair of Germans creeping through the grass, trying to get the drop on his GIs. The two Americans lined them up and cut them down. Powell cleaned up the German helmet in question and shipped it back home. It hung on a nail in his barn, a .30 caliber hole running all the way through.

During the Battle of the Bulge, Powell took a small combat patrol out to find the forward thrust of the German armor. He found it. He and his guys were out on their own behind enemy lines for 4 days. When they were making their way back, they encountered a U.S. antitank unit and were “captured.” Otto Skorzeny’s SS men in GI uniforms had done their job well, and nobody trusted anybody.

The trigger-happy AT guys asked them who had won the World Series at gunpoint. Powell said he was a country boy from southern Mississippi. When they were watching the World Series, he was out chasing opossums to feed his family. He told them he had no time for baseball, and they let him pass.

He saw the death camps with the living scarecrows. He captured a “baby factory” in Frankfurt filled with little blonde-haired boys sired by SS men with willing frauleins. He said he didn’t know what happened to the little girls.

Powell relayed dozens of stories, and it was evident he had some strong opinions about a lot of things. He vigorously opposed females in the military. He said real war was too horrible for women. I’ve not lived what he lived. I lack the credibility to question him.

He had great respect for artillery, though he didn’t care much for the .30 carbine — not enough spunk downrange. He never saw a Thompson submachine gun in an infantry unit. Each squad had a BAR, and he respected it. He loved the Garand. He said they were a good bit more efficient with their ammo back then. He said, “I’ll kill way more people with that M1 than these boys will today with them fast-firing guns.” I believed him.

Despite only having a sixth-grade education. Powell successfully completed a military career as a master sergeant, raised a whole bevy of productive children, spent a lifetime paying taxes and making the world a better place. Looking around his outbuildings with a dozen restored tractors and piles of beautifully resurrected old engines speaks to his mechanical proclivities.

We talked for three hours, and I took five pages of notes. The experience of sitting with my son and listening to a man describe what Omaha Beach smelled like was quite literally priceless. Mr. Powell may be gone now, but today, we stand on the shoulders of giants.

The heroes who terminated the gunman at The Covenant School in Nashville, Tennessee last week are speaking out.

Officer Rex Engelbert of the Metropolitan Nashville Police Department led the charge.

Upon entry, it took him approximately 2 minutes and 15 seconds to engage the 28-year-old shooter.

“I really had no business being where I was,” Engelbert said after he responded to the call of an “active shooter” while en route to the Police Academy for routine administrative tasks.

“You can call it fate or God or whatever you want. I can’t count on my hands the irregularities that put me in that position when the call for service went out for an active deadly aggressor at a school,” he said.

Engelbert was joined by Detective Sgt. Jeff Mathes. The two men had never met before. But along with several others, they answered the call to go inside the private Christian school to stop the shooter.

“I had never seen Rex in my life,” Mathes explained, as reported by WSMV. “When we got there, he had already unlocked the door. Not knowing what I was going into, I walked through that door without hesitation.”

The responding officers immediately ran toward the gunfire.

“I looked for the nearest staircase I could find, because I could tell [the gunfire] was above my head,” said Englebert, who added, “I couldn’t get to it fast enough.”

Police Chief John Drake applauded the actions of his men.

“They did what we were trained to do,” Drake said. “They got prepared and went right in – knowing that every moment wasted could cost lives.”

“Their efforts also saved lives,” he continued. “They were able to protect these kids as well.”

“No one ever said it would be easy,” Drake said. “But they said it would be worth it. I’m totally proud of my men for what they did.”

You cannot make this up, and even if you could, the actual facts would read like something out of a really strange movie script about good versus just plain dumb.

When Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker last month rushed to sign a brand new gun control bill before the Legislature adjourned (only to re-convene about 24 hours later), something happened nobody saw coming. County sheriffs up and down the Prairie State loudly declared they would not enforce the new law, which banned so-called “assault weapons” and “high-capacity magazines.” It requires current owners to register their guns with the Illinois State Police.

How this may play out is ripe for speculation. By the time you read this, at least one federal lawsuit involving the Illinois State Rifle Association, Second Amendment Foundation and Firearms Policy Coalition will have been filed. There could be more. It all means that the new Illinois law might be headed for a collision with the Constitution’s Second Amendment.

This certainly appears to be what the sheriffs of at least 80 Illinois counties were thinking when they posted letters saying essentially the same thing.

“As your duly elected Sheriff,” the letter says, “my job and my office are sworn to protect the citizens … This is a job and responsibility that I take with the utmost seriousness. The right to keep and bear arms for defense of life, liberty and property is regarded as an inalienable right by the people of this country …”

“Therefore, as the custodian of the jail and chief law enforcement official, I proclaim that neither myself nor my office will be checking to ensure that lawful gun owners register their weapons with the State, nor will we be arresting or housing law-abiding gun individuals that have been arrested solely with non-compliance of this Act.”

Published reports, and reliable sources, confirm Pritzker was furious when the sheriffs went public with their opposition. When he intimated the lawmen would lose their jobs, at least two different Illinois sources told me between laughs that the governor does not have the authority to fire elected sheriffs.

Meanwhile, Out West

When sheriffs in Washington State got wind of the gun control package put forth by Gov. Jay Inslee, which also involves a ban on semi-auto rifles, the Washington State Sheriff’s Association circulated a letter signed by Kittitas County Sheriff Clay Myer —president of the group — and it was not congenial.

“Governor Inslee,” Sheriff Myers wrote, “has announced plans for significant new restrictions on the ownership of firearms by law-abiding Washingtonians. We, members of the Washington Sheriffs’ Association, believe the proposed restrictions will serve to erode constitutionally protected rights without addressing the root causes of violent crime. We are particularly concerned with the proposed so-called ‘assault weapons ban’ and ‘permit to purchase’ laws.”

A few paragraphs later, Myers put it bluntly: “The rise in violent crime that so concerns citizens has happened even as regulations and restrictions on firearm ownership have grown. Of course, this is because the people who commit violent crimes simply don’t concern themselves with obeying rules about guns.”

Murder and mayhem is up in Washington, and so is the number of concealed pistol licenses. As the year wrapped up, there were just short of 697,000 active CPLs in circulation, according to data from the state department of licensing.

It’s not the first time county sheriffs have “just said no.” Back in 2018 and early 2019, many Washington sheriffs announced they would not actively enforce provisions of Initiative 1639, an extremist gun control measure passed by voters.

Some sheriffs in New York State say they will not “aggressively” enforce that state’s new gun law, which is being challenged by at least two federal lawsuits. A few sheriffs in Oregon have said essentially the same thing about provisions of Measure 114, the gun control initiative passed there last November.

A Good Man Gone

The problem with being an old gun guy is that it becomes more frequent we must say “goodbye” to a good friend, who happens to have also been just a plain good person.

Robert E. “Bob” Hodgdon, whose family name is part of the fabric of American metallic cartridge reloading, passed away Jan. 13. Having been born in August 1938, Hodgdon had a good run that covered a lot of ground. He and his brother, J.B. helped build the company founded by their father, Bruce Hodgdon, and today that name is iconic in the industry for the variety of reloading propellants for rifles, shotguns and handguns. According to an obituary the family posted, he “also assisted with the design and lead the team constructing the Pyrodex Plant in Herington, Kan. in 1979 and helped to design and build The Bullet Hole, a 44-station indoor shooting range in 1967.”

I served with Hodgdon on the NRA board of directors more than 20 years ago, and you could not find a more devoted fellow where perpetuation of the shooting sports, and protection of the Second Amendment, was concerned. He was a kind and gentle soul, a person you’d be delighted to share a campfire with, and someone who was as devoted to his family as his professional pursuits. He was father to four children, Chris (Adele) Hodgdon, Heidi (Erwin) Rodriguez, Stacie (Bryant Larimore) Hodgdon and Alisa Hodgdon — and grandfather of 11 and great-grandfather to eight.

A native of Kansas, he grew up in suburban Kansas City. He attended Baker University in Baldwin City, Kan., and graduated Summa Cum Laude from the University of Kansas. He served in the U.S. Air Force and the Air Force Reserves.

He served as president of Hodgdon for more than 20 years and then as board chairman from 2014 to 2017.

Hodgdon volunteered in several civic organizations, and was a member of the Westside Family Church in Lenexa, Kan.

Additionally, he was a founding member of the National Shooting Sports Foundation, a member of the Kansas State Rifle Association, and founding member of the Kansas Sportsmen’s Alliance.

Men like Bob Hodgdon are very rare.

https://youtu.be/VOHYrA1UzpY

I recognize a lot of places that were in LA & San Francisco from long lost youth. Back when the insanity was just starting out. Enjoy a brief look back when this was a great place to live! Grumpy