Category: Hard Nosed Folks Both Good & Bad

Charles Young (March 12, 1864 – January 8, 1922) was the third African-American graduate of West Point, the first black U.S. national park superintendent, first black military attaché,\.

Also the first black man to achieve the rank of colonel, and highest-ranking black officer in the Regular Army until his death in 1922.

Contents

Early life and education

Charles Young was born in 1864 into slavery to Gabriel Young and Arminta Bruen in Mays Lick, Kentucky, a small village near Maysville.[1]

However, his father escaped from slavery early in 1865, crossing the Ohio River to Ripley, Ohio, and enlisting in the Fifth Regiment of Colored Artillery (Heavy) near the end of the American Civil War.[1]

His service earned Gabriel and his wife their freedom, which was guaranteed by the 13th Amendment after the war. Arminta was already literate, which suggests she may have worked as a house slave before her freedom.

The Young family settled in Ripley when Gabriel was discharged in 1866, deciding that opportunities there in Ohio were probably better there than in postwar Kentucky. Gabriel Young received a bonus by continuing to serve in the Army after the war, and he had enough to buy land and build a house.

Charles Young attended the all-white high school in Ripley, the only one there who was African-American. He graduated in 1880 at the top of his class. He then taught for several years in the new black high school opened in Ripley.[1]

West Point

In 1883, Young took the competitive examination for appointment as a cadet at United States Military Academy at West Point.

He had the second highest score in his district, but the top candidate decided not to go and Young reported to West Point in 1884.

There was then one other black cadet, John Hanks Alexander, who had entered in 1883 and graduated in 1887. Young and Alexander shared a room for three years at West Point.

Although regularly discriminated against, Young did make several lifelong friends among his later classmates, but none among his initial class.[2]

He had to repeat his first year when he failed mathematics. He later failed an engineering class, but he passed it the second time when he was tutored during the summer by George Washington Goethals, the Army engineer who later directed construction of the Panama Canal and who as an assistant professor took an interest in Young.

(It was not unusual for cadets to need tutoring in some subjects. Young’s strength was in languages, and he learned to speak several.)[1]

As one of the very first African-Americans to attend and graduate from West Point, Charles Young faced challenges far beyond his white peers. He experienced extreme racial discrimination from classmates, faculty and upperclassmen.

Hazing was not an unusual practice at the male dominated military academies. Charles Young, however, was subjected to a disproportionate amount of abuse because of his color.[3]

There are many stories about Young’s struggles at West Point. Upon arrival to West Point, Young was welcomed in as “The Load of Coal”.[4]

Once, in the mess hall, a white cadet proclaimed that he would not take food from a platter that Young had already taken from. Young passed the white cadet the plate first, allowing him to take from it, then he himself took from the plate.[5]

Upperclassmen targeted and demerited Young 140 times, which would have been considered unusually high.[6] Whereas Young’s peers were referred to by their last names, Young was called “Mr. Young” as a kind of feigned deference.[4]

One of Young’s greatest struggles at West Point was loneliness.[7] A white classmate of Young’s, Major General Charles D. Rhodes, later reported that it was a practice of Young to converse with some of the servants at West Point in German to maintain some human interaction.[8]

Towards the end of his five-year stay at West Point, the merciless discrimination and taunts decreased.[9]

Because of his perseverance, some of Young’s classmates began to see past the color of his skin. Despite this and by his own admission, Charles Young’s time at West Point was fraught with difficulty.[10]

Career

Young graduated in 1889 with his commission as a second lieutenant, the third black man to do so at the time (after Henry Ossian Flipper and John Hanks Alexander, and the last one until Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. in 1936).

He was first assigned to the Tenth U.S. Cavalry Regiment. Through a reassignment, he served first with the Ninth U.S. Cavalry Regiment, starting in Nebraska.

His subsequent service of 28 years was chiefly with black troops—the Ninth U.S. Cavalry and the Tenth U.S. Cavalry, black troops nicknamed the “Buffalo Soldiers” since the Indian Wars.

The armed services were racially segregated until 1948, when President Harry S. Truman initiated integration by executive order, which took some years to complete.[11]

Marriage and family

After getting established in his career, Young married Ada Mills on February 18, 1904 in Oakland, California.

They had two children: Charles Noel, born in 1906 in Ohio, and Marie Aurelia, born in 1909 when Young and his family were stationed in the Philippines.[12]

Military service

Young began his service with the Ninth Cavalry in the American West: from 1889-1890 he served at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, and from 1890-1894 at Fort Duchesne, Utah.

In 1894, Lieutenant Young was assigned to Wilberforce College in Ohio, an historically black college (HBCU), to lead the new military sciences department, established under a special federal grant.[13]

A professor for four years, he was one of several outstanding men on staff, including W.E.B. Du Bois, who became his close friend.[1]

When the Spanish–American War broke out, Young was promoted to the temporary rank of major of Volunteers on May 14, 1898.

He commanded the 9th Ohio Infantry Regiment which was, in the terminology of the day, a “colored” (i.e. African-American) unit.

Despite its name, the 9th Ohio was only battalion sized with four companies. The short war ended before Young and his men could be sent overseas.

Young’s command of this unit is significant because it was probably the first time in history an African-American commanded a sizable unit of the United States Army and one of the very few instances prior to the late 20th Century.

He was mustered out of the volunteers on January 28, 1899, and reverted to his regular army rank of first lieutenant. He was promoted to captain in the 9th Cavalry Regiment on February 2, 1901.[14]

National Park assignments

In 1903, Young served as captain of a black company at the Presidio of San Francisco. He was then appointed acting superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant national parks, becoming the first black superintendent of a national park.

(At the time the military supervised all national parks.)

Because of limited funding, however, the Army assigned its soldiers for short-term assignments during the summers, which made it difficult for the officers to accomplish longer term goals. Young supervised payroll accounts and directed the activities of rangers.

Young’s greatest impact on the park was managing road construction, which helped improve the underdeveloped park and allow more visitors to enjoy it.

Young’s men accomplished more that summer than had been done under the three officers assigned to the park during the previous three summers.

Captain Young’s troops completed a wagon road to the Giant Forest, home of the world’s largest trees, and a road to the base of the famous Moro Rock. By mid-August, the wagons of visitors could enter the mountaintop forest for the first time.[15]

With the end of the brief summer construction season, Young was transferred on November 2, 1903, and reassigned as the troop commander of the Tenth Cavalry at the Presidio.

In his final report on Sequoia Park to the Secretary of the Interior, he recommended the government acquire privately held lands there, to secure more park area for future generations. This recommendation was noted in legislation to that purpose introduced in the United States House of Representatives.

Other military assignments

Charles Young cartoon by Charles Alston, 1943

With the Army’s founding of the Military Intelligence Department, in 1904 it assigned Young as one of the first military attachés, serving in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

He was to collect intelligence on different groups in Haiti, to help identify forces that might destabilize the government. He served there for three years.

In 1908 Young was sent to the Philippines to join his Ninth Regiment and command a squadron of two troops. It was his second tour there. After his return to the United States, he served for two years at Fort D.A. Russell, Wyoming.

In 1912 Young was assigned as military attaché to Liberia, the first African-American to hold that post.

For three years, he served as an expert adviser to the Liberian government and also took a direct role in supervising construction of the country’s infrastructure.

For his achievements, in 1916 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) awarded Young the Spingarn Medal, given annually to the African American demonstrating the highest achievement and contributions.[16]

In 1912 Young published The Military Morale of Nations and Races, a remarkably prescient study of the cultural sources of military power.

He argued against the prevailing theories of the fixity of racial character, using history and social science to demonstrate that even supposedly servile or un-military races (such as Negroes and Jews) displayed martial virtues when fighting for democratic societies.

Thus the key to raising an effective mass army from among a polyglot American people was to link patriotic service with fulfillment of the democratic promise of equal rights and fair play for all. Young’s book was dedicated to Theodore Roosevelt, and invoked the principles of Roosevelt’s “New Nationalism”.[17]

During the 1916 Punitive Expedition by the United States into Mexico, then-Major Young commanded the 2nd squadron of the 10th United States Cavalry. While leading a cavalry pistol charge against Pancho Villa‘s forces at Agua Caliente (1 April 1916), he routed the opposing forces without losing a single man.[18]

Because of his exceptional leadership of the 10th Cavalry in the Mexican theater of war, Young was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in September 1916.

He was assigned as commander of Fort Huachuca, the base in Arizona of the Tenth Cavalry, nicknamed the “Buffalo Soldiers”, until mid 1917.[16] He was the first African American to achieve the rank of colonel in the US Army.[19]

Forced retirement

With the United States about to enter World War I, Young stood a good chance of being promoted to brigadier general.

However, there was widespread resistance among white officers, especially those from the segregated South, who did not want to be outranked by an African American.

A lieutenant who served under Young complained to the War Department, and Secretary of War Newton Baker replied that he should “either do his duty or resign.” John Sharp Williams, senator from Mississippi, complained on the lieutenant’s behalf to President Woodrow Wilson.

The President overruled Baker’s decision and had the lieutenant transferred. (In 1913, Southern-born Wilson had segregated federal offices and established discrimination in other ways.) Other white officers in the 10th Cavalry became encouraged to apply for transfers as well.

Baker considered sending Young to Fort Des Moines, an officer training camp for African Americans. However, Baker realized that if Young were allowed to fight in Europe with black troops under his command, he would be eligible for promotion to brigadier general, and it would be impossible not to have white officers serving under him.

The War Department instead removed Young from active duty, claiming it was due to his high blood pressure.[20] Young was placed temporarily on the inactive list (with the rank of colonel) on June 22, 1917.

In May 1917 Young appealed to Theodore Roosevelt for support of his application for reinstatement. Roosevelt was then in the midst of his campaign to form a “volunteer division” for early service in France in World War I.

Roosevelt appears to have planned to recruit at least one and perhaps two black regiments for the division, something he had not told President Wilson or Secretary of War Baker.

He immediately wrote to Young offering him command of one of the prospective regiments, saying “there is not another man [besides yourself] who would be better fitted to command such a regiment.” Roosevelt also promised Young carte blanche in appointing staff and line officers for the unit. However, Wilson refused Roosevelt permission to organize his volunteer division.[21]

Young returned to Wilberforce University, where he was a professor of military science through most of 1918.

On November 6, 1918, after he had traveled by horseback from Wilberforce, Ohio, to Washington, D.C. to prove his physical fitness, he was reinstated on active duty as a colonel.[15] Baker did not rescind his order that Young be forcibly retired.[20]In 1919, Young was reassigned as military attaché to Liberia.

Young died January 8, 1922, of a kidney infection while on a reconnaissance mission in Nigeria.

His body was returned to the United States, where he was given a full military funeral and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery across the Potomac River from Washington, DC.

He had become a public and respected figure because of his unique achievements in the Army, and his obituary was carried in the New York Times.[22]

Honors and legacy

Young’s house near Wilberforce, Ohio

- 1903 – The Visalia, California, Board of Trade presented Young with a citation in appreciation of his performance as Acting Superintendent of Sequoia National Park.

- 1916 – The NAACP awarded him the Spingarn Medal for his achievements in Liberia and the US Army.

- He was elected an honorary member of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity.

- 1922 – Young’s obituary appeared in the New York Times, demonstrating his national reputation.

- 1922 – His funeral was one of few held at the Memorial Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery, where he was buried in Section 3.[22]

- Charles E. Young Elementary School, named in his honor, was built in Washington, D.C. The first elementary school in Northeast D.C., it was built to improve education in the city’s black neighborhoods. It was one of several schools closed in 2008, but the building now houses Two Rivers Public Charter School.

- 1974 – The house where Young lived when teaching at Wilberforce University was designated a National Historic Landmark, in recognition of his historic importance.[16]

- 2001 – Senator Mike DeWine introduced Senate Resolution 97, to recognize the contributions of the Buffalo Soldiers of the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry, and Colonel Charles D. Young.[23]

- 2013 – President Barack Obama used the Antiquities Act to designate Young’s house as the 401st unit of the National Park System, the Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument.[24]

Military medals

Young was entitled to the following medals:

- Indian Campaign Medal

- Spanish War Service Medal

- Philippine Campaign Medal

- Mexican Service Medal

- World War I Victory Medal

Dates of rank

- Cadet, United States Military Academy – 15 June 1884

- 2nd Lieutenant, 10th Cavalry – 31 August 1889 (transferred to 9th Cavalry 31 October 1889)

- 1st Lieutenant, 7th Cavalry – 22 December 1896 (transferred to 9th Cavalry 1 October 1897)

- Major (Volunteers), 9th Ohio Colored Infantry – 14 May 1898

- Mustered out of Volunteers – 28 January 1899

- Captain, 9th Cavalry – 2 February 1901

- Major, 9th Cavalry – 28 August 1912 (transferred to 10th Cavalry 19 October 1915)

- Lieutenant Colonel – 1 July 1916

- Retired as Colonel – 22 June 1917[25]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Brian Shellum, Black Cadet in a White Bastion: Charles Young at West Point, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska, 2007, pp. 6–13, accessed 8 Jun 2010

- Jump up^ Shellum, Brian (2006). Black Cadet in a White Bastion: Charles Young at West Point. U of Nebraska Press. p. 132.

- Jump up^ Shellum, Brian G. (2006). Black cadet in a white bastion : Charles Young at West Point. Lincoln [u.a.]: Univ. of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803293151.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Charles Young”. The Crisis. The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc.: 104 1 July 1923.

- Jump up^ “Charles Young”. The Crisis. The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc.: 155 1 February 1922.

- Jump up^ Heinl, Nancy G. (1 May 1977). “Col. Charles Young: Pointman”. The Crisis. The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc.: 173.

- Jump up^ Heinl, Nancy G. (1 May 1977). “Col. Charles Young: Pointman”. The Crisis. The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc.: 174.

- Jump up^ Kilroy, David P. (2003-01-01). For Race and Country: The Life and Career of Colonel Charles Young. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275980054.

- Jump up^ Heinl, Nancy G. (1 May 1977). “Col. Charles Young: Pointman”. The Crisis. The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc.: 173–174.

- Jump up^ Kilroy, David P. (2003). For race and country : the life and career of Colonel Charles Young. Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Praeger. ISBN 9780275980054.

- Jump up^ “Chapter 12: The President Intervenes”. Center of Military History. US Army. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- Jump up^ Brian G. Shellum, Black Officer in a Buffalo Soldier Regiment: The Military Career of Charles Young, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska, 2010, p. xx, accessed 9 Jun 2010

- Jump up^ James T. Campbell, Songs of Zion, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 262, accessed 13 Jan 2009

- Jump up^ Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army, 1789-1903. Francis B. Heitman. Vol. 1. pg. 1066.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Sequoia National Park”

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Colonel Charles Young”. Buffalo Soldier. Davis, Stanford L. 2000. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- Jump up^ “Lost Battalions: The Great War and the Crisis of American Nationality” (2005), pp. 41–42; Military Morale of Races and Nations, by Charles Young (1912).

- Jump up^ “Pursuing Pancho Villa”. Presidio of San Francisco. National Park Service. 6 December 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- Jump up^ “Col. Charles Young Dies in Nigeria; Noted U.S. Cavalry Commander Was the Only Negro to Reach Rank of Colonel”. New York Times. January 13, 1922. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rawn James, Jr. (22 January 2013). The Double V: How Wars, Protest, and Harry Truman Desegregated America’s Military. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 49–51. ISBN 978-1-60819-617-3. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- Jump up^ The correspondence among Roosevelt, Young and F. S. Stover (who was raising money for the regiment) is in the John Motley Collection, Tredegar Museum. A fuller account is in Richard Slotkin, Lost Battalions: The Great War and the Crisis of American Nationality, (2005), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Charles D. Young”, Arlington National Cemetery, accessed 9 Jun 2010

- Jump up^ Charles Davis, “Colonel Charles Young”, Buffalosoldier.net, accessed 9 Jun 2010

- Jump up^ [1], accessed 7 April 2013

- Jump up^ Official Register of Commissioned Officers of the United States Army. December 1, 1918. pg. 1009.

Sources

- This article is based in part on a document created by the National Park Service, which is part of the U.S. government. As such, it is presumed to be in the public domain.

Further reading

- Chew, Abraham. A Biography of Colonel Charles Young, Washington, D.C.: R. L. Pendelton, 1923

- Greene, Robert E. Colonel Charles Young: Soldier and Diplomat, 1985

- Kilroy, David P. For Race and Country: The Life and Career of Charles Young, 2003

- Shellum, Brian G., Black Cadet in a White Bastion: Charles Young at West Point, Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 2006.

- Shellum, Brian G., Black Officer in a Buffalo Soldier Regiment, The Military Career of Charles Young, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

- Stovall, TaRessa. The Buffalo Soldier, Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 1997

- Stewart, T. G. Buffalo Soldiers: The Colored Regulars in the United States Army, Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2003

- Sweeney, W. Allison (1919), History of the American Negro in the Great World War – infobox photograph

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Young (United States Army). |

- “Charles Young”, National Park Service

West Point admits Parkland student Peter Wang who died saving classmates

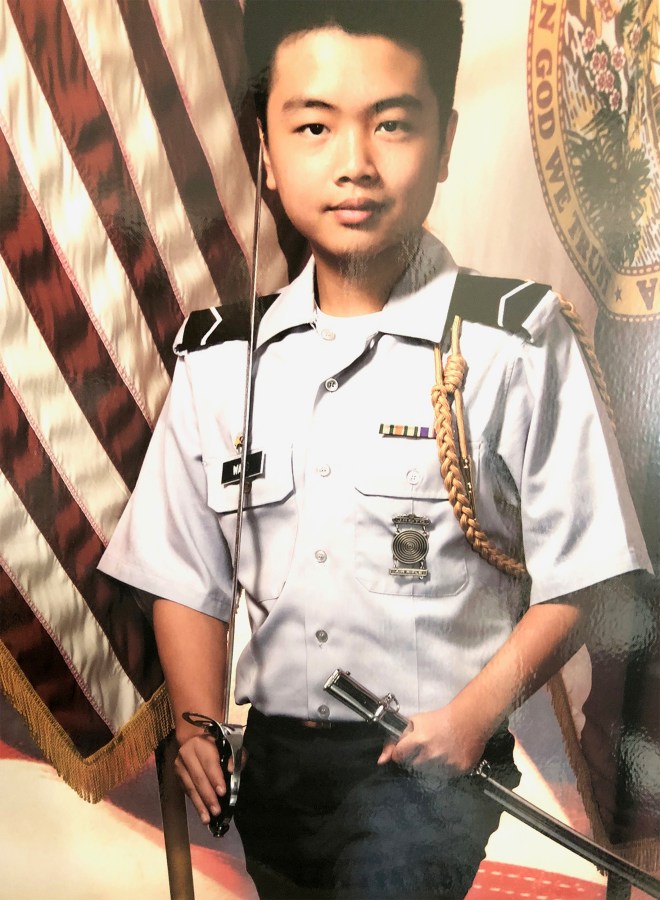

Fifteen-year-old Peter Wang, who was killed while trying to help classmates escape from a gunman at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, was posthumously accepted to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point on Tuesday “for his heroic actions on Feb. 14, 2018” and then buried in his Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (JROTC) uniform.

Wang, the U.S. Military Academy said in a statement, “had a lifetime goal to attend USMA.”

Related: These are the 17 victims of the Parkland school shooting

“It was an appropriate way for USMA to honor this brave young man,” it read. “West Point has given posthumous offers of admission in very rare instances for those candidates or potential candidate’s (sic) whose actions exemplified the tenets of Duty, Honor and Country.”

Wang would have been in the Class of 2025, a West Point spokesman said.

The letter was hand-delivered to Wang’s parents by a uniformed Army officer at the funeral home in Coral Springs, Florida, where a gut-wrenching funeral was held as grieving relatives wept beside the slain teenager’s open casket.

When the shooting started at the high school in Parkland, the Brooklyn, N.Y.-born cadet yanked open a door that allowed dozens of classmates, teachers and staffers to escape, officials said.

But as he stood at his post in his JROTC uniform and held the door open, Wang was shot and killed — one of the 17 students and staffers who died in the school that day.

“For as long as we remember him, he is a hero,” classmate Jared Burns told NBC Miami.

“He was like a brother to me and possibly one of the kindest people I ever met,” longtime friend Xi Chen added.

Gov. Rick Scott has directed the Florida National Guard to honor Wang, who was a freshman, and two other JROTC members who were killed — Alaina Petty, 14, and Martin Duque, 14.

Also, a petition calling on Congress to give Wang a full military funeral had collected nearly 70,000 signatures as of Tuesday afternoon, some 30,000 short of the 100,000 needed to get a response from the White House.

“Wang died a hero, and deserves to be treated as such, and deserves a full honors military burial,” the petition states.

Missing in the mix of hundreds of bug-out stories is a forth right and candid self appraisal of lessons learned containing practical experience along with deep humility and honest self examination. High Desert expressed a willingness to share his and his wife’s adventure with TwoIceFloes and we eagerly embraced the opportunity to post his story as a three part series. – Cognitive Dissonance

It was the summer of 2011, and for all practical purposes it was smooth sailing. My wife and I often commented to each other how drama and stress free our lives had become. Unfortunately we were blissfully unaware of the squall line rapidly approaching from behind.

The epiphany struck us like a bolt out of the blue. But rather than providing clarity and calm, this profound revelation was a violent tempest. The following six years brought dramatic shifts to our belief systems, state of mind, living conditions and more – dramatically swinging the pendulum back and forth before finally compelling us to seek balance and peace of mind.

We were not significantly affected by the financial crash a couple years prior (2008-09) partly because we both had home-based businesses in niche markets which provided a lower middle-class income. But a more important factor was our lack of debt. Not one to “keep up with the neighbors”, we lived comfortably but always within our means.

We had previously paid off the mortgage, both of us owned older used vehicles and we never charged purchases we couldn’t afford to pay off at the end of each month. We had some meager investments, but fortunately years earlier we had moved into the right neighborhood. Meaning over the years, our neighborhood had evolved into one of the hottest residential markets in the Metro area.

Most of our disposable income (along with a lot of sweat-equity) was spent modernizing our home. Essentially we considered our primary residence to be our own private 401(k) plan. In addition, we owned a small cabin on twenty six acres of land where we planned to eventually retire. Our son was about to graduate from high school with honors and was (still is) a delight to spend time with. Our state of mind at the time was one oflight, love and abundance.

Our life-changing insight came about due to boredom. Purposely not caught up in the rat-race of Western civilization and long term self-employed, we had a fair amount of free time to pursue other interests. Being introverts, we devoted most evenings to home activities. Usually my wife would conduct research for her book publishing business. And I, usually brain-dead from working on the computer all day, would zone out and watch some streaming TV.

Not one to watch just any old dung produced for the masses, it didn’t take me long to burn through every decent movie and documentary out there. By then, total boredom had me reconsidering my second and third string watch lists, desperate for quality entertainment. For some inexplicable reason I had placed a documentary in my queue which I had blown past on numerous occasions as not interesting enough to watch. But, just as inexplicably, I had never deleted it.

One overly warm summer night in 2011 I cranked up the central A/C, retreated to the family room and decided to finally watch “Collapse” by Michael Ruppert. That documentary was my red pill moment. Even after watching it twice in a row, I found it difficult to believe what I was only now beginning to understand.

On the one hand, the truths presented in the documentary were 180 degrees out of sync with my core belief systems. On the other, I knew deep down I had been living in the make believe world of the Matrix. When I convinced my wife to take a break and watch it with me, it only took one viewing for her to recognize the truth as presented. It was truly an epiphany for both of us, although not of the type one would usually classify as such.

Our life was about to change in ways we could not imagine. And change again and again as we rode the swinging pendulum back and forth, totally out of balance. We’d been through a lot during our many years of marriage, but we had no idea what lay before us. Waking up so suddenly and always one for self-directed action, all hell was about to break loose.

As we began to absorb our new understanding about how the world really works, my wife and I began to work out how to deal with the events we knew for certain were just around the corner. We devoted the next few months to exhaustively researching who, what, when, where and why.

Although I intuitively knew the new reality as presented was correct, I needed to convince myself I wasn’t just being stupid. After all, what did I really know about manipulated financial markets, mono-agriculture, fiat currency, systemic corruption and more importantly, what to do when all the complex systems began to collapse due to their inherent chaos.

The red pill had done its job in providing the initial jolt, but we were now strangers in a foreign land. Our initial reaction was to shelter in place as it were, maybe stock up on some supplies, install a wood stove (totally illegal where we lived) build a small greenhouse in our very small backyard and perhaps get some stun guns and mace for personal defense.

My wife’s primary concern was food. How would she feed our family if the grocery stores closed? My primary concern was our personal safety. Somehow I needed to defend the castle and loved ones against the “golden horde”, a new term picked up during my research. After all, we lived in a big city with neighbors literally twelve feet away on either side.

What happened next was quite odd. We woke up one morning, rolled over to face each other and simultaneously said “we have to get out of the city.” This is no little thing to accomplish. We owned our home, two businesses and our son was still in high school. Where would we go and what do we need that place to be?

Our research went into overdrive.

One thought was to make our cabin the bug-out location. We even began to stock long-term food there. However the cabin was old, the well was of poor quality and so was the soil. And unfortunately that gorgeous view of the city lights down the mountain meant those in the city could see us.

Additionally, the only usable flat land was at the end of the driveway right next to the cabin. How would we house other family members and close friends in a small cabin with no room to park an RV or several vehicles? We began to wonder if there was a better place out there, but still within driving distance of the city.

Is there a gear higher than overdrive? You know, the gear that allows you to simultaneously get a house (or two) ready for sale, research every real estate website for hours each day, close down an active publishing business and figure out what and when to tell your teenage child his world was about to be rock and rolled.

As is the case with nearly everyone else, our life was a bit complicated. My wife has a special-needs brother who requires lots of attention and supervision. At that time my father was 90 and needed more and more care. We were both in our 50’s and I was in the midst of a long recovery from a two year stretch of multiple surgeries after an accident.

Even at the age of 50, and nearly 30 years after completing my “Thank You for Your Service” gig, I still thought of myself as that 19-year-old airborne infantryman, naively fearless and invincible. I was capable of anything, including living forever. The accident I was recovering from was my first warning that life-long beliefs could quickly be shattered. It gave me a new perspective to the old saying “things can change in an instant.”

With the benefit of 20-20 hindsight, if ever there was a legitimate plea for temporary insanity we hereby stake our claim. Although our approach was in its entirety logical, we fell into a “desperate measures for desperate times” mentality, driven by fear and panic. It was not a balanced approach by any measure.

We finally decided it was impossible to deal with all of this simultaneously. We put the cabin up for sale “as is”, though we would not put much effort into selling it since it remained our Plan B. After months of fruitless searching for the ideal retreat, the cabin oscillated between being Plan B and Plan A. Our choice in that matter would soon be forcibly removed; more on that subject later.

Trying to accomplish all of the above during the day, at night I would explore new concepts such as The Long Emergency, The Fourth Turning, the sixth mass extinction event and so much more including all the rightthings a survival retreat should encompass. My wife dedicated her evenings to researching every potential retreat property for sale in the state. Because of the situation with her brother, my father and our son, the new place had to be within a day’s drive of our family.

She developed an efficient web search system to quickly eliminate unsuitable properties. Several ‘needs’ were non-negotiable parameters: water well, septic, acreage, somewhat remote, buildings in good condition. Even with those restrictions, there were plenty of options. It was critically important to check the oil/gas/fracking permits issued for the area of each property we had an interest in.

We knew from first-hand experience property owners in our state have ZERO rights if someone else owns the mineral rights and wants to exploit them. This issue alone eliminated entire sections of the state. My wife also researched the water well permit for each potential property to determine the age of the well, its depth, flow rate, source of water and so on. This constraint eliminated a fair number of properties. Without a good source of water, nothing else matters.

We discussed the remaining properties and applied our secondary list of wants and needs. How many people could the property support? Can we actually grow food there? Was it already off-grid? My wife would show me ten properties and I’d quickly eliminate them because of population density or other security related concerns. I would show her ten properties and she would rule them out due to altitude (hard to grow food above the timberline) distance from family or the condition of the buildings.

Our largest constraint was our refusal to take on a mortgage. We knew we could get a good price for our home in the city; the entire state was (and continues to be) in an ever-expanding housing bubble. But rural didn’t necessarily equate to inexpensive in this state.

It was all a bit overwhelming. Couldn’t we please, please, just go back to a life of blissful ignorance? Unfortunately it was too late to ask for the Blue Pill.

Compounding our difficulties (as with so many other people who suddenly wake up) we thought it was our duty to enlighten our friends and family of the coming perils. For anyone who has tried to do so, I don’t need to explain how poorly it went. Since we believed doomsday was just around the corner, we opted instead to buy/build the retreat and assume they would come.

After almost a year of searching online and physically examining properties, we were growing increasingly anxious to move forward. Our primary residence was ready to go on the market, my father had passed away, my wife’s publishing business had been sold and we’d already had that heart to heart conversation with our son.

At eighteen years of age and with his entire life ahead of him, he wanted no part of moving to a remote location to become a homesteader. We respected his decision, although during the initial conversation he accused us of abandoning him. Ultimately we all worked together to make sure he could continue on his path until things fell apart, either with his plans or the world.

In the summer of 2012 we all took a weekend off to stay in a small town and visit a top candidate for the new retreat. In so many ways the property was perfect. Nearly new structures surrounded by public lands, already set up for off-grid living, just a few full-time neighbors (but not too close) and plenty of flat land. We made a good offer.

The following week was filled with buyer’s remorse. Would we have any money left from the sale of our home? Was the retreat too remote? Were we really ready to change our entire lifestyle and take on such a large project? That Thursday we decided the best thing to do was forget the whole thing. We would move into our cabin and make the best of it.

But nature was set to intervene.

On Friday, a massive wildfire started near our cabin. By Saturday, our time to commit to the realty contract would expire; we had to make a final decision. While sitting in a hotel room to avoid an open house weekend at our primary residence, we watched updates on the expanding fire and realized there was very little chance our cabin would survive. It would turn out to be one of the most destructive wildfires our state ever experienced. It was also the second property we’ve lost to wildfire.

It seemed some unseen force was guiding us to the new retreat. It must be fate. It must be our destiny.

The following five years proved to be the biggest challenge we ever faced. We were on a mission to save ourselves, family and friends. How could so many things go so terribly wrong?

All this and more will be covered in part two of this three part series.

02/19/2018

High Desert