Category: Grumpy’s hall of Shame

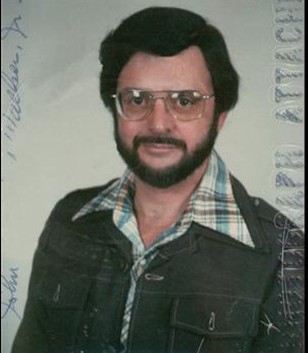

Notorious spy John Walker died on Aug. 28, 2014. The following is a story outlining Walker’s spy ring from the June 2010 issue of U.S. Naval Institute’s Naval History Magazine with the original title: The Navy’s Biggest Betrayal.

Twenty-five years ago the FBI finally shut off the biggest espionage leak in U.S. Navy history when it arrested former senior warrant officer John A. Walker.

To hear the United States’ most notorious naval spy tell it, were it not for his ex-wife, Barbara – the weak link his Soviet handlers had warned him about – his espionage might have continued. As it was, however, John Walker’s ferreting went on far too long. A few more years and, had he been employed in a conventional job, he could have retired on a pension. Indeed, he already enjoyed a U.S. Navy pension after retiring in 1976 as a senior warrant officer.

The Navy, in which John Walker served for 20 years, was enormously damaged by his espionage. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger concluded that the Soviet Union made significant gains in naval warfare that were attributable to Walker’s spying. His espionage provided Moscow “access to weapons and sensor data and naval tactics, terrorist threats, and surface, submarine, and airborne training, readiness and tactics,” according to Weinberger. A quarter-century after John Walker’s arrest, it is illuminating to revisit the story of his naval spy ring, both for what it reveals about espionage versus security and for how it highlights the ambitions and frailties at the heart of spying.

Building a Naval Career

John Anthony Walker Jr. was born in 1937, the middle son of a Warner Brothers film marketer and an Italian-American mother. Nicknamed “Smilin’ Jack,” he attended Catholic school and became an altar boy; however, his childhood was traumatic. His father descended into a hell of alcoholism and lost his job. Bankrupt, the family moved near the boy’s grandparents in Scranton, Pennsylvania. The entrepreneurial John Jr. secured a paper route, sold home products door to door, and worked as a movie usher, and on his 16th birthday bought a car with his savings.

In late 1955 Walker joined the Navy as a radioman and served on board a destroyer escort before joining the crew of the aircraft carrier USS Forrestal (CV-59). While on shore leave in Boston during the winter of 1957, he met Barbara Crowley. They married soon afterward, and children followed, three daughters by 1960. After qualifying at submarine school, Walker was assigned to the Razorback (SS-394) for a Pacific deployment. While serving in her, Walker, then a petty officer, received his top secret cryptographic clearance and passed the Personnel Reliability Program, a psychological evaluation to ensure that only the most reliable personnel have access to nuclear weapons.

His submarine participated in surveillance missions off the Soviet port of Vladivostok and in the flotilla observing the July 1962 Starfish Prime high-altitude nuclear test. Walker’s efficiency reports were uniformly excellent, and he was assigned to the Blue Crew of the Polaris ballistic missile submarine Andrew Jackson (SSBN-619), then under construction at Mare Island Naval Shipyard. On board the boat, Walker impressed the executive officer enough that when he was named to command the Gold Crew of the Simon Bolivar (SSBN-641), he recruited the petty officer to lead his radio room. Walker first qualified on maintenance of cryptographic equipment in early 1963. Along the way, he passed his high school general education degree exams as well as Navy promotion tests, rising through grades to chief petty officer and warrant officer. These were the makings of a fine enlisted career. Ten years in, John Walker had served with some distinction on board half a dozen vessels, was a plank owner on a pair of “boomers,” had attained warrant officer rank, and had run the radio shop of a nuclear missile submarine.

Life, however, grated on Smilin’ Jack. Walker disliked the impersonal nature of his big ships, and his membership in the tight-knit crews of smaller vessels was long behind him. The lengthy underwater patrols in the ballistic missile subs, during which there were just a handful of brief communications with home, tried him.

Those cruises were also hard on his family, which by now included a son, Michael Lance. Meeting the kids all over again after a patrol was difficult for everyone, and according to Walker, he discovered Barbara philandering with family members, ignoring the household, and – shades of his father – drinking more and more. Walker seems to have despised the Navy for encouraging alcoholism among Sailors and their families. He invested his savings in land outside Charleston, South Carolina, planning to build a car park to give his wife a constructive outlet. He later opened a bar on the property instead, but the marginal venture left Warrant Officer Walker strapped for cash. Casting about for some means of righting his financial boat, he drove a cab and shuttled rental cars among cities, but it was not enough.

A Second Career

Espionage became Walker’s way out, though in his telling political disaffection also played a role. He suspected John F. Kennedy’s assassination had been engineered by government and corporate leaders intent on preventing the President from toning down the Cold War. In his memoir, Walker recounted his intellectual evolution from 1950s John Bircher to Cold War denier. He said he began to realize the Soviets were not the aggressive adversary Americans feared. “The farce of the cold war and the absurd war machine it spawned,” he commented, “was an ever-growing pathetic joke to me.”

One bracing fall day in October 1967 Chief Warrant Officer Walker, then assigned as a watch officer at Atlantic Fleet Submarine Force headquarters in Norfolk, decided to correct the military balance – and balance his checkbook – by leaking top secret information to Moscow. Taking the first step, he photocopied a document at headquarters and slipped the copy in his pocket. The next day he hopped into his red 1964 MG sports car, drove to Washington, walked into the Soviet Embassy, and asked to see security personnel.

Yakov Lukasevics, an internal security specialist at the embassy, had no idea what to do with the American who came bearing documents and said he wanted to spy. The papers, however, needed to be evaluated, and so he telephoned the KGB rezident , or station chief, Boris A. Solomatin. KGB rezidenturas (stations) were wary of walk-ins, persons who spontaneously offered their services. The Soviets even used the term “well-wishers” to denote such persons. And the idea of an American striding right into the Soviet Embassy in Washington, which was under constant FBI surveillance, immediately suggested a trap.

“I have an interesting man here who walked in off the street,” Lukasevics told Solomatin. “Someone must come down who speaks better English.”

Another KGB man presently spoke to Walker, who identified himself and said he wanted to earn money and “make arrangements for cooperation.” The KGB officer then took the documents upstairs to Solomatin. As it happened, the 43-year old rezident was a naval buff, having grown up in the Black Sea port of Odessa. Solomatin recognized that some of Walker’s documents concerned U.S. submarines, vessels that particularly plagued the Soviet Fleet. Of greater importance, the National Security Agency (NSA) document Walker had purloined before leaving work listed the following month’s settings for the American KL-47 encryption machine. The Soviets had already received some NSA papers from a different spy, and after comparing markings and format realized Walker’s settings document, called a key list, was genuine.

On the spot Solomatin decided to take a chance. For a KGB station chief personally to meet a prospective agent was unprecedented, but Solomatin spent the next two hours talking privately with Walker. The American favorably impressed him by saying nothing about love for communism, which most phonies emphasized. This was strictly business. Walker received a few thousand dollars cash as a down payment and was smuggled off the embassy compound in a car. Thus began the Navy’s most damaging spy case.

Solomatin, who had not previously paid special attention to the U.S. Navy, now boned up on the subject.

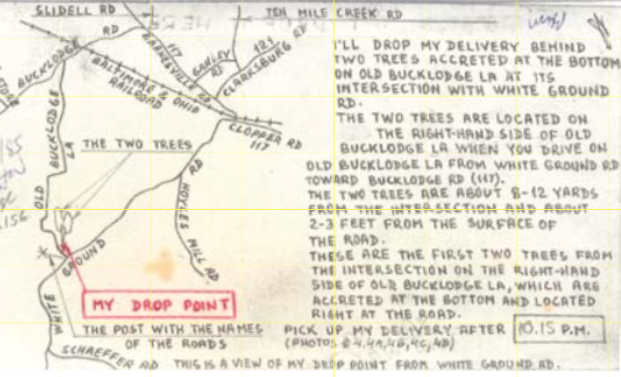

He kept a very tight rein on the Walker operation, assigning Oleg Kalugin, his deputy for political intelligence (Line PR), as the American’s manager and Yuri Linkov, a naval spy, as his case officer. Kalugin spent weeks driving around the Washington area to identify and carefully record spots for “dead drops,” places Walker would deposit packages of intelligence and pick up cash and instructions. During a meeting outside a northern Virginia department store within a month of Walker’s embassy visit, the warrant officer handed over a bigger pile of Navy documents, and Linkov gave him the locations for his first few drops-offs plus more money. Those were the only face-to-face meetings the KGB had with John Walker for a decade. Some versions of the tale maintain that his espionage began in 1968; however, Solomatin, Kalugin, and Walker all agree that it began in October 1967 at the Soviet Embassy.

Only a handful of other KGB officials ever had anything to do with Walker. A stovepipe fed his material to the deputy chief of the First Directorate, the KGB’s foreign intelligence unit, and just a couple of assistants. Awarded the Order of the Red Banner for Walker’s recruitment, Solomatin was promoted to deputy chief of intelligence. In 1968, when the KGB created the Sixteenth Directorate, its counterpart to NSA, the Walker case passed from Line PR to the new agency, but the tight security surrounding it was preserved.

Whether the KGB had an immediate use for Walker’s KL-47 key list is still not clear. In early January 1968, however, the spy delivered to the Soviets a KW-7 encryption machine key list that would quickly prove useful. Later that month, North Korea captured the spy ship USS Pueblo (AGER-2) in international waters and with it a KW-7 device along with manuals and other documents. According to historian Mitchell B. Lerner, a leading authority on the affair, within two days of seizing the Pueblo , North Korea dispatched an aircraft to Moscow containing almost 800 pounds of cargo, presumably from the spy ship. The KGB quickly dispatched a team of intelligence experts to the port of Wonsan, North Korea, where the vessel had been taken. U.S. intelligence detected transmission of an enormous fax to Moscow, presumably the texts of manuals for cryptographic equipment on board the Pueblo .

Thereafter, Moscow had continued access to American naval communications until the U.S. system was entirely changed.

Life As a Spy

John Walker’s trickle of intelligence meanwhile became a flood. According to Walker’s account, he mostly supplied the Soviets with old key lists – much less zealously guarded – and the KGB never pressed him for current or future ones. In fact, the Soviets advised Walker to avoid future material as well as maintenance manuals. Also, their plan for clandestine drops provided for only two per year, and he claimed that the KGB never demanded more frequent exchanges, which means their take of current/future material had to be limited to a couple of months annually.

Walker also maintained that much of what he gave the Soviets concerned such obsolescent systems as the World War II – vintage KL-47, which featured a seven-rotor encryption machine similar to the German Enigma, and the KW-37, an early online, or automated, encryption system. As for the later-generation KW-7 system, Walker said he only provided the Soviets with its key lists for random future dates. Probably few commentators accept his version of what he handed over. If his claim that the KGB showed no desire for current or future keys is accurate, it puts an interesting light on Soviet gains from his espionage.

Walker nevertheless provided a huge array of other secret Navy and U.S. documents to America’s Cold War adversary. These included operational orders, war plans, technical manuals, and intelligence digests. The KGB devised and furnished its spy with an electronic device that could read the KL-47’s rotor wiring and gave him a miniature Minox camera. At Norfolk, he used his status as an armed forces courier to smuggle documents from headquarters to his bachelor officer quarters (BOQ) room, where he photographed them. There was such a stream of papers he had to be selective. Walker estimated that photographing just 20 of the hundreds of messages that crossed his desk during a watch would have required more than 100 rolls of film over six months, yet initially everything he left at a dead drop needed to fit inside a single soda can.

Later, while on training duty at San Diego, Walker had less access to top secret documents and had to rely on a classified library. Smuggling out material meant getting it past multiple checkpoints staffed by Marine guards. He also forged the papers required to show renewal of his security clearance. This spy enjoyed amazingly good fortune.

But John Walker’s luck ran out with his family. He sometimes spent nights at the BOQ instead of the family’s home. Barbara Walker had suspected her husband of sexual adventures – true, as it happened – and looked through his things. Family financial problems that had seemed insuperable were suddenly solved. Walker pointed to his moonlighting as the source of his money, but Barbara remained unconvinced. And then, within a year of her husband becoming a spy, she found a grocery bag in which Walker had secreted a pile of classified documents. Confronted with the discovery, he admitted to his espionage and took Barbara along to one of his dead drops in a dubious attempt to involve her in his crime. From the beginning, the KGB had warned Walker never to reveal anything to his wife or other family members. Though Barbara did nothing immediately, the seeds of John Walker’s downfall were planted.

On the West Coast and while assigned to the combat stores ship Niagara Falls (AFS-3), the spy’s journeys to drop his gleanings to the KGB became much more onerous. One 1972 drop required a flight from Vietnam to the United States, a brief cover visit home, and then rejoining his ship in Hong Kong. When Walker returned to Norfolk to work at Amphibious Force Atlantic headquarters in the summer of 1974, the problems were ameliorated, but the transfer conflicted with his desire to remain afloat and away from Barbara.

The naval spy’s solution was to retire from the Navy. He believed that he could then work more effectively as a network manager, delivering to the Soviets information gathered by others. By the time he separated from the service, Walker had already begun dabbling in private investigating. Later, he took a job at Wackenhut and then opened his own firm. He also divorced Barbara, but not before again bringing her along to one of his drop sites.

Building the Ring

John Walker’s network began with an old Navy friend, Senior Chief Petty Officer Jerry Whitworth, also a radioman, who had left the service but re-enlisted in the fall of 1974. He then volunteered for a billet at Diego Garcia, a previous duty station. Whitworth was active by the summer of 1975, when Walker put in for retirement. The more experienced spy forwarded many packets of Whitworth’s intelligence to the KGB. Possibly the best resulted from his tour on board the Niagara Falls in the same post Walker once held. When the ship went into dry dock, Whitworth was reassigned to Naval Communications Center Alameda. There, however, he found that clandestinely photographing documents was harder. Walker bought a van, for which the Soviets reimbursed him, in which Whitworth could do his camerawork while it sat in a parking lot near work.

With Walker free to travel after his retirement and Whitworth delivering the goods, the spymaster offered the Soviets more frequent intelligence deliveries. Again the KGB specifically refused, although it invited Walker to a face-to-face meeting in Casablanca in the summer of 1977 during which his Soviet contact denounced his recruitment of a new agent. Walker agreed to annual clandestine meetings in Vienna and not to bring in any more agents. He later claimed that during one of the sidewalk encounters in the Austrian capital he was secreted away and debriefed by a group of men who included KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov. Others claim that Andropov personally oversaw Walker’s espionage, which was unlikely.

In late 1980, a visit to Alameda by a Naval Investigative Service (NIS) team to solve a rape case frightened Whitworth. He not only became skittish but also pecuniary, deliberately ruining a batch of his photographs in an attempt to get the KGB to pay twice. Whitworth carried off a foot-high stack of documents from his last post on board the Enterprise (CVN-65) with the intent to continue delivering his stream of classified information after leaving the Navy, which he did in October 1983. Among the materials the Soviets obtained from him were cable traffic plus photographs of, and some key lists for, the KW-7, KY-8, KG-14, KWR-37, and KL-47 cryptographic systems. Though older crypto setups predominated, the take included data on the newest U.S. secure phone system.

Aware of Whitworth’s increasing reluctance to spy and despite Walker’s promises to the KGB, in 1983 the spymaster solicited his son, Michael, a freshly minted yeoman on board the Nimitz (CVN-68) who worked in the ship’s administration office. (In 1979 he had attempted but failed to draw in his youngest daughter, Laura Walker Snyder, who was then in the Army but pregnant and planning to leave the service.) Michael copied more than 1,500 documents for the KGB, including material on weapon systems, nuclear weapons control, command procedures, hostile identification and stealth methods, and contingency target lists. He also included such ordinary items as copies of the Nimitz ship’s newspaper.

Owing money to the spymaster, Arthur L. Walker, John’s older brother who was a retired Navy lieutenant commander working for a defense contractor, played the game. He produced repair records on certain warships plus damage-control manuals for another. John Walker’s rationalizations aside, this “family of spies” approach to espionage was a security breach waiting to happen, since suspicion of any family member would likely result in questioning of others, and the master spy was perfectly aware that Barbara Walker harbored nothing but ill-will toward him.

End of Walker’s Espionage

A most troubling aspect of the Walker affair is how it could have gone on for 18 years without authorities uncovering the leak. There is no indication that counterintelligence was even aware of, much less moving to combat, the Walker network. Norfolk FBI spy catcher Robert W. Hunter claimed he knew that an “elusive master spy . . . was out there,” but no attention focused on Walker until he was given away.

John Walker’s operational security finally cracked in 1984, and fissures opened at every seam. That May Jerry Whitworth, afflicted with guilt or anxious to make a deal, opened an anonymous correspondence with the FBI in San Francisco using the name “RUS” and offering dark secrets. Whitworth, however, could not bring himself to follow through, and the FBI special agents involved were unable to track him down. In the end the RUS letters would be connected to John Walker, but only after the fact.

Then Barbara Walker denounced her ex-husband to the FBI. In November, after daughter Laura convinced her to speak to authorities, Barbara told the FBI field office in Boston that she had important information, and on 29 November a special agent from Hyannis interviewed her. The spy’s ex-wife told him of her growing suspicion of her husband as far back as the 1960s, his admission to spying, and her accompanying Walker to dead drops near Washington. She described actions in those deliveries that dovetailed with KGB techniques.

The agent, however, noted in his report that Barbara appeared to have been drinking when she greeted him at her door and that during the interview she drank a large glass of vodka. She was also evasive when asked why she had not reported the spying earlier. He surmised that her allegations could be the result of her alcohol abuse and ill feelings toward her ex-husband, graded her information as meriting no follow-up, and sent the report to Boston, where it was filed away.

A month later, an FBI supervisor making a routine quarterly check of inactive files noted the Barbara Walker report and forwarded it to the bureau’s Norfolk office because the alleged espionage centered there. Joseph R. Wolfinger, special agent in charge at Norfolk, obtained headquarters’ approval to open an investigation. On 25 February he assigned the case to Robert Hunter, who had brought the Boston report to his attention.

The pieces then quickly fell into place. Laura Walker Snyder was interviewed about her father’s attempt to recruit her and added details to her mother’s account, though both Laura and Barbara were recognized as having personal problems that would make them not fully credible witnesses. In early March, headquarters authorized a full field investigation, code-named Windflyer, involving its foreign counterintelligence unit. The Naval Investigative Service also came into play since Michael Walker, a suspect by then, was an active-duty Sailor. Laura Snyder telephoned her father at the behest of the FBI, which recorded the conversation in which he evinced interest in her rejoining the military or perhaps the CIA. The FBI tapped Walker’s phones, and the NIS interviewed hundreds of persons who had known him and obtained a confession from Michael on board the Nimitz .

The end for John Walker finally came on 20 May when the FBI arrested him after confiscating 127 classified documents from the Nimitz that he had left at a dead drop. A search of his home turned up plentiful evidence of the spy ring, including records of payments to “D” (Jerry Whitworth), who turned himself in to authorities on 3 June. Brother Arthur was also arrested.

In exchange for limits to his charges, John Walker made a deal to discuss his espionage in detail and plead guilty, and Michael also copped a plea. Arthur Walker was tried in August and found guilty. Whitworth went before a court in the spring of 1986. At his trial John Walker retaliated for the RUS letters, which would have betrayed him, by painting his friend’s participation in the starkest terms. Found guilty, Whitworth was fined $410,000 and given 365 years in prison. As for the Walkers, Arthur was sentenced to three life terms plus a $250,000 fine, John received a life term, and Michael 25 years. In February 2000 Michael Walker was released for good behavior. John and Arthur Walker, meanwhile, will be eligible for parole in 2015.

Assessing the Damage

Many observers believe the Walker spy ring created the most damaging security breach of the Cold War. Director of Naval Intelligence Rear Admiral William O. Studeman declared that no sentence a court could impose would atone for its “unprecedented damage and treachery.” Secretary of the Navy John H. Lehman tried to overturn John Walker’s plea agreement but was restrained by Secretary Weinberger. Oleg Kalugin, the KGB officer who had first managed Walker, wrote that his was “by far the most spectacular spy case I handled in the United States.”

Walker and his colleagues compromised a huge array of secrets. Jonathan Pollard, another naval spy apprehended during 1985, the Year of the Spy, gave Israel a greater quantity of documents (estimated at 1.2 million pages), but the Walker material, with its cryptographic secrets, has to be judged as the worse loss.

Soviet spy chief Boris Solomatin offered a more nuanced perspective when author Pete Earley interviewed him in Moscow nearly ten years after Walker’s arrest. Refusing to compare the Walker case with that of former CIA counterintelligence officer Aldrich Ames, another high-profile spy for the Soviet Union, he observed that agents must be judged on the content of the information they deliver. Ames provided the names of Russians spying for the United States and thus affected the KGB-CIA espionage war. Ames’ information “would have been used to identify traitors,” he said. “That is a one-time event. But Walker’s information not only provided us with ongoing intelligence, but helped us over time to understand and study how your military actually thinks.” John Walker had been the Soviets’ key source on Navy submarine missile forces, which Solomatin viewed as the main component of the American nuclear triad. The KGB spymaster also noted that Walker helped both superpowers avoid nuclear war by enabling Moscow to appreciate true U.S. intentions – a goal the American articulated as one of his aims.

Among the still-murky aspects of the Walker affair is the question of what impact his intelligence had on the Vietnam War. While on board the Niagara Falls , Walker served in the combat theater, so he is believed to have compromised the Navy’s theater cipher settings. Oleg Kalugin maintained that the North Vietnamese benefited from the Walker intelligence. Observers claimed Moscow gave Hanoi data enabling North Vietnam to anticipate B-52 strikes and naval air operations. Solomatin, however, disputed that.

As deputy chief of the KGB’s First Directorate, Solomatin himself helped decide what intelligence went to Hanoi, as well as the Soviet Union’s other allies. He asserted that little was shared and it was given in the most general terms, precisely to avoid exposing the KGB’s prize agent. The logic is inescapable. A CIA operation would have been run the same way.

Even without the B-52 charge, the John Walker spy ring was enormously damaging to United States security. In the history of Cold War espionage only a handful of spies operated as long as Walker (British intelligence official Kim Philby and FBI agent Robert Hanssen are the obvious comparisons), and none had comparable access to military secrets.

No spy ring ever functioned as long as Walker’s without the other side becoming aware of a leak. While some specific secrets compromised during the Cold War, such as information about the atomic bomb, were intrinsically more valuable than Walker’s, no agent supplied such consistently high-grade intelligence over an equivalent time frame. As Boris Solomatin noted: “You Americans like to call him the ‘ spy of the decade.’ Perhaps you are right.”

Sources:

Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB (Basic Books, 1999).

John Barron, Breaking the Ring: The Bizarre Case of the Walker Family Spy Ring (Houghton-Mifflin Company, 1987).

Howard Blum, I Pledge Allegience . . . The True Story of the Walkers: An American Spy Family (Simon & Schuster, 1987).

Peter Earley, Family of Spies: Inside the John Walker Spy Ring (Bantam, 1988).

Peter Earley, “Boris Solomatin Interview,” Crime Library on truTV.com.

Robert W. Hunter and Lynn Dean Hunter, Spy Hunter: Inside the FBI Investigation of the Walker

Espionage Case (Naval Institute Press, 1999).

Oleg Kalugin, The First Directorate (St. Martin’s Press, 1994).

Mitchell B. Lerner, The Pueblo Incident: A Spy Ship and the Failure of American Foreign Policy (University Press of Kansas, 2002).

Ronald J. Olive, Capturing Jonathan Pollard: How One of the Most Notorious Spies in American History Was Brought to Justice (Naval Institute Press, 2006).

John Prados, The Soviet Estimate: U.S. Intelligence Analysis and Soviet Strategic Forces (Princeton University Press, 1986).

Frank J. Rafalko, ed. A Counterintelligence Reader: vol. 3, Post World War II to the Closing of the 20th Century (National Counterintelligence Center, 2004).

John A. Walker Jr., My Life as a Spy: One of America’s Most Notorious Spies Finally Tells His Story (Prometheus Books, 2008).

Collection of Smithsonian National Museum of American History (2015.0252).

During the war, the United States government incarcerated many people in camps and prisons across the home front. The government declared hundreds of thousands of Japanese, Italian, and German people across the US and Latin America to be enemy aliens, and confined them in prisons and camps. [1]

The government sent Conscientious Objectors to work camps to support the war effort, imprisoning them if they refused. And in the Territory of Hawai’i, the military declared martial law, restricting the civil liberties of those living there. [2]

Enemy Alien Detention Camps

Within hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the President issued Executive Orders 2525, 2526, and 2527. These declared all foreign nationals of Japan, Italy, and Germany (respectively) as enemy aliens. Several thousand were immediately arrested, having been previously identified by the FBI as allegedly dangerous to the United States. [3]

Collection of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/2015634494/).

By the end of the war, the government had incarcerated more than 31,000 suspected enemy aliens and their families, not including those sent to War Relocation Camps.

Most of those held as enemy aliens were German and Japanese; there were also a few hundred Italians held. Archaeology done at the sites of enemy alien internment camps has documented the day-to-day realities of these sites. [5]

Japanese War Relocation Authority Incarceration Centers

In February 1942, the President issued Executive Order 9066. It established “military areas” across California and in parts of Oregon, Washington, and Arizona. People – including American citizens – could legally be excluded from these places.

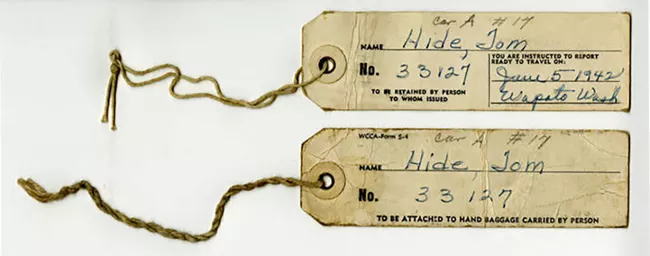

Collection of Washington State Universities Libraries: Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, Tom Hide Collection (SC 014.1).

With only 48 hours’ notice before the government detained them, few people were able to make arrangements for their homes, businesses, and property. Some white Americans helped by buying and holding on to their possessions until after the war. But most were unable to make arrangements and lost everything except what they were able to carry with them. [8]

The first stop was at a Control Center, where the government issued families a number and told them when and where to report. Families became known only by their numbers. At the allocated time, families — wearing their number tags — boarded buses or trains that took them to assembly centers.

Collection of National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 537019).

In the WRA relocation centers, four or five families lived together in sparse, tar-papered barracks. Many residents worked for the camps or for farms beyond the fences, earning up to $19 per month.

Those considered “troublemakers” were sent to the higher security War Relocation Center at Tule Lake, California. Archaeology done at several relocation centers provides information on the day-to-day lives of those incarcerated. This includes the persistence of Japanese cultural activities (sumo, gardens) and illicit activities (making and consuming sake). [10]

The last American incarceration center for people of Japanese descent closed in 1948. [11] In 1982, the US government found that the incarceration of Japanese and Japanese Americans stemmed from “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” [12]

Forced Relocation of Alaska Natives

Following the Japanese invasion of Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, over 800 Native Alaskans were forcibly relocated, “for their own safety.” Allowed to bring only a few items like one bag and one blanket each, the US military shipped them thousands of miles from their homes.

Collection of the National Park Service.

Prisoner of War Camps

The United States was host to more than 425,000 Prisoners of War. These were mostly Germans, but tens of thousands of Italians and thousands of Japanese POWs were also interned here. [14] After capture overseas, the military shipped POWs to the US, where they were imprisoned in one of over 700 camps.[15] Unlike those held as enemy aliens or sent to the WRA centers, the treatment of POWs was dictated by the Geneva Convention.

They were fed well, given clothing and toiletries, and had access to the same medical and dental treatment as US troops. [16] Many Americans felt that the POWs were being treated too well, while American citizens were dying overseas. Archaeological studies at POW camp sites in the US document the experiences of those held there. [17]

The government leased out as many as 265,000 POWs to fill non-military labor shortages. Many POWs worked in agriculture, picking produce, packing meat, and canning product.

Farmers paid the government 45 cents per hour per POW (about $8 in 2023). The prisoners earned 80 cents per day (about $14 in 2023) for their labor, paid in camp scrip or chits. This system prevented them from having American cash if they escaped. POWs were able to spend their wages in camp canteens, with access to goods including candy, tobacco, and low-alcohol beer and wine. [18]

In September 1943, Italy surrendered to the Allies and declared war on Germany. This released Italian POWs from the Geneva Convention, allowing them to do military work.[19] This released Italian POWs from the Geneva Convention, and allowed them to take on military work. [19] Offered the chance to move to lower-security camps and work towards defeating Germany, many Italian POWs volunteered.

Collection of the US Air Force (080112-F-2034C-203.JPG).

Americans Incarcerated by Enemy Forces

When Japan captured American territories, they generally sent US military members to POW camps in Japan, China, and elsewhere. Civilians, however, found themselves under often brutal control by the Japanese.

Afterwards, they blindfolded and killed the Americans and buried them in a mass grave. An escapee (later caught and beheaded) chiseled the date of the massacre in a nearby rock. [23]

On Guam, civilians suffered starvation, rape, murder, and forced labor under Japanese occupation. Near the end of the war, the Japanese forced up to 15,000 Chamorro to march to incarceration camps like Manenggon in the island interior. There, those who survived lived with inadequate shelter, no sanitary facilities, no medical care, and very little food until American forces freed them in July 1944. [24]

Wikimedia, Public Domain.

Conscientious Objectors

The Selective Service Act of 1940 contained provisions for conscientious objectors. The military assigned those opposed to combat to noncombatant military roles. Those who were opposed to military service at all were “assigned to [unpaid] work of national importance under civilian direction.” [25]

Some in the CPS served as “human guinea pigs” in a series of medical experiments done by the Office of Scientific Research & Development and the Office of the Surgeon General. These experiments included documenting the effects of starvation, cold weather, high altitude, and malaria. CPS workers logged over 8 million personnel days of work during the program. [26]

There were over 150 Civilian Public Service camps across the United States, including Puerto Rico. Several of them took over former CCC camps. The first, Patapsco Camp in Maryland, opened on May 15, 1941. Over 6,000 men who refused to work at all as conscientious objectors went to prison for violating the Selective Service Act. The CPS camps were closed in March 1947. [27]

Martial Law in Hawai’i

Within hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Governor of the Territory of Hawai’i declared martial law. This suspended the constitutional rights of everyone in Hawai’i, putting all legal authority in the hands of the US Army. [28]

The army censored the press, long distance telephone calls and cables, and all civilian mail. They instituted a curfew and blackout, and required the registration and fingerprinting of all civilians (except small children).

Many residents of Japanese descent lost their jobs. The military replaced the civil court system, trying all crimes in military courts. They wouldn’t allow jury trials, believing that jurors in Hawai’i could not be impartial. Ninety-nine percent of the estimated 55,000 civilian cases heard in the military courts resulted in guilty verdicts. [29]

In a ruling towards the end of the war, the Supreme Court described the treatment of Hawaiian civilians as “a wholesale and wanton violation of constitutional liberties.” [30] The military reinstated some functions of the civilian government in March 1943, but martial law remained in effect until October 1944. [31]

It was not just those incarcerated or who were affected by enemy attacks on the home front who felt the effects of the war. Across the Greater United States, Americans found many items in short supply and were asked to recycle and to grow their own food.

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

Frankly I just don’t care who you f*ck (Children & Animals excepted) as long as you can get the job done. Grumpy