On October 14, 1888, Louis Le Prince released The Roundhay Garden Scene. With a run time of 2.11 seconds and starring Annie Hartley, Adolphe Le Prince, Joseph Whitley, and Sarah Whitley, this was the world’s first moving picture. The Roundhay Garden Scene changed the world. Here’s a link.

Dwayne Johnson is the most highly-paid actor in the world. This is The Rock celebrating Halloween with his family. Though I’ve never met him, Big Dwayne seems like a pretty cool guy.

Dwayne Johnson is the most highly-paid actor in the world. This is The Rock celebrating Halloween with his family. Though I’ve never met him, Big Dwayne seems like a pretty cool guy.Ours is a generation raised on movies. In 2020 the movie industry brought in $25.9 billion. That’s down from $35.3 billion the year before thanks to the Covid pandemic. The top four most successful actors in 2020 were Dwayne Johnson, Ryan Reynolds, Mark Wahlberg, and Ben Affleck. During that one year, The Rock pulled down a cool $87.5 million.

With those kinds of numbers, the movie industry can obviously afford top-grade talent. I am a professional writer. I bang out gun-related prose in exchange for ammo money. By contrast, the scriptwriters who drive these Hollywood blockbusters make some serious coin. For that kind of investment, Hollywood producers expect a quality product.

Everybody knows that a great movie turns on its villain. Vapid leading men are a dime a dozen, and hot girls with fake bosoms and a convincing scream are even cheaper. However, it takes talent to build a proper Bad Guy. Hannibal Lecter, Darth Vader, Agent Smith, the Joker, Voldemort, and Hans Gruber were some of the best.

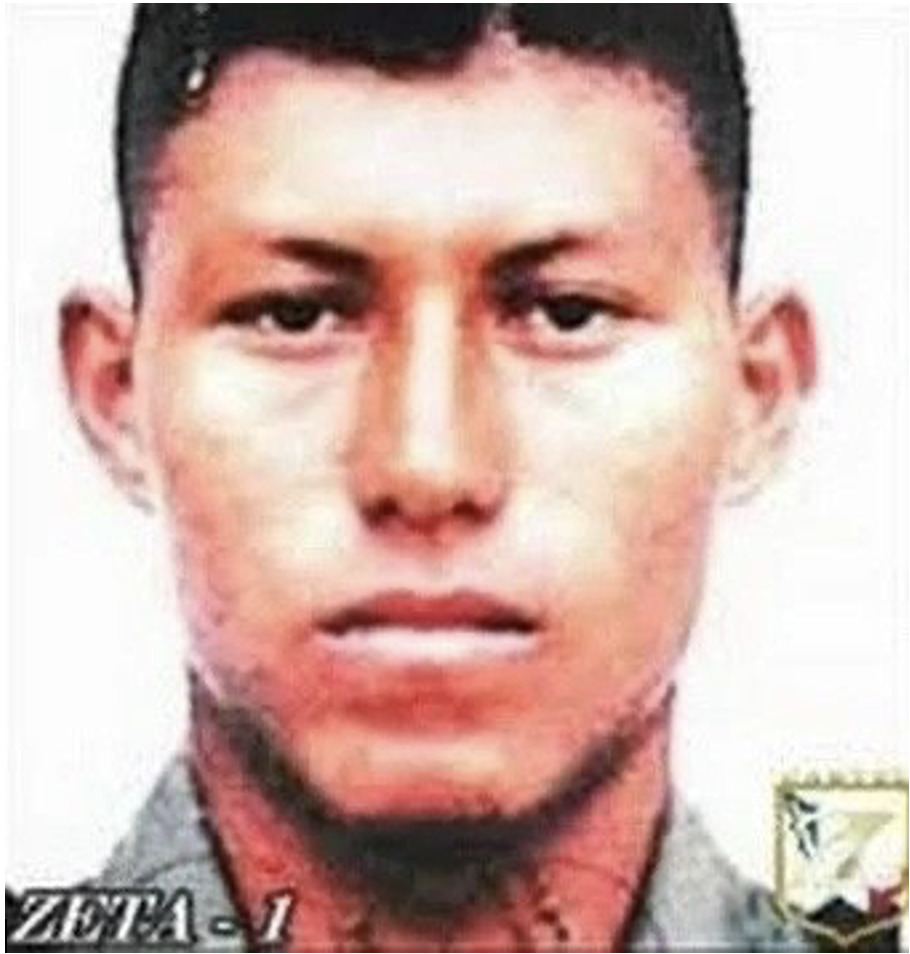

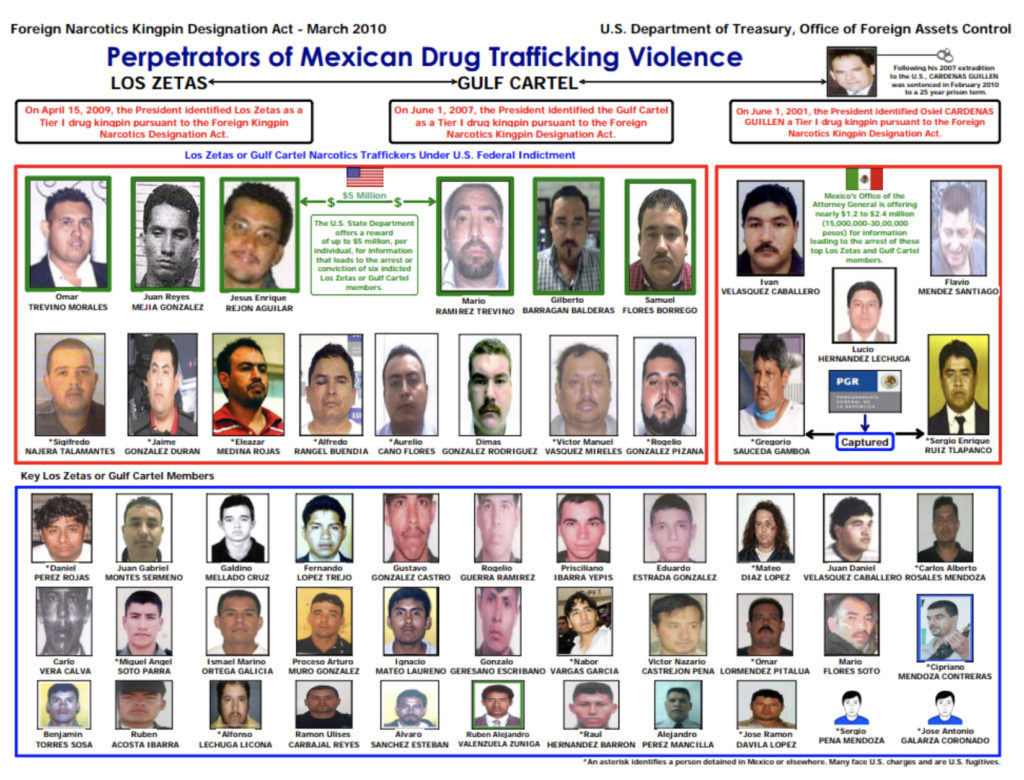

Sometimes you trip over a story in the real world that is even more compelling than a Hollywood screenplay. As all good tales turn on their villains, that was what first caught my eye in this case. Today we will explore the short life and violent death of Z-1, Arturo Guzmán Decena. Guzmán Decena put the bloodthirsty in “bloodthirsty Mexican drug cartel”. He was the founder and leader of Los Zetas, some of the most soulless butchers on the planet.

Origin Story

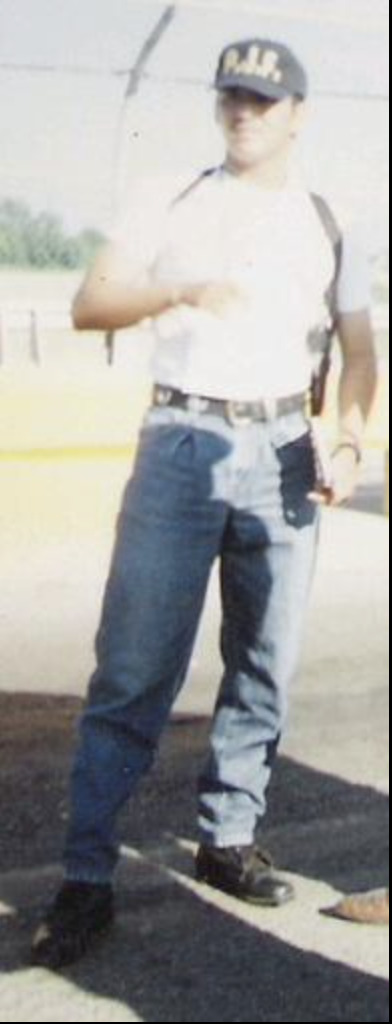

Arturo Guzmán Decena was born into abject poverty in January of 1976 in Puebla, Mexico. In a world where nobody had anything, Decena saw military service as his ticket out of hell. Once he joined the Army he found that he had a knack for the business. His natural talent and capacity for aggression landed him a billet with the elite Grupo Aeromovil de Fuerzas Especiales or GAFE. This Mexican Army Special Forces unit specialized in COIN or counter-insurgency operations.

Guzmán Decena and his unit were trained by US Special Forces advisors and IDF (Israel Defense Force) contractors. Their mission was to find, fix, and eliminate major personalities in Mexican drug trafficking organizations. GAFE operators were extremely good at what they did.

More than 3,000 Zapatista rebels seized a number of border communities in the southern state of Chiapas in 1994. The insurgents were trying to make a statement against crushing poverty and the PRI (Institutional Revolution Party), the sole political party ruling Mexico at the time. The GAFE broke the back of the uprising in short order, killing 34 rebels and capturing three. The bodies were subsequently discovered discarded on a remote riverbank. Their noses and ears had been sliced off.

For all the vociferous whining about American Law Enforcement shortcomings, corruption among American cops is thankfully fairly rare. By contrast, cops in many foreign lands see bribery, extortion, and sometimes murder as a routine part of the job. In some parts of Mexico, bribes are viewed as “benefits” to supplement their otherwise modest salaries. However, before Arturo Guzmán Decena the lines separating the Good Guys from the Bad were still fairly clear-cut. Decena changed all that.

Greener Pastures

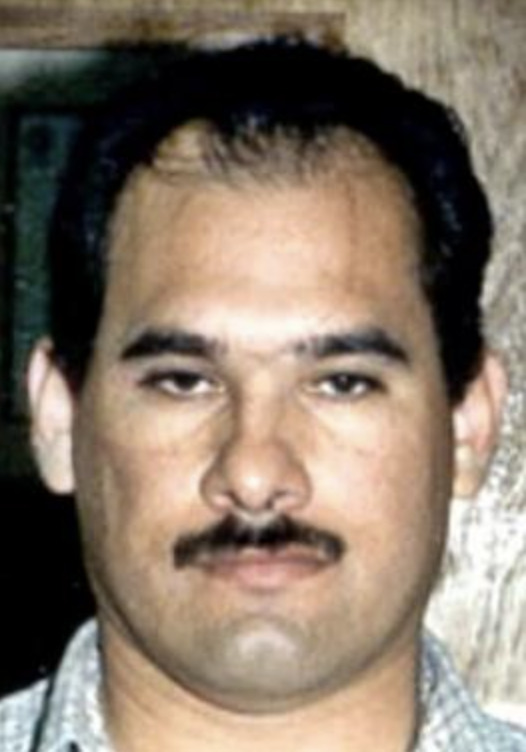

Arturo Guzmán Decena was one of the most effective GAFE operators. His star was rising. He was soon promoted to security chief and transferred to Miguel Aleman in the northern state of Tamaulipas. While there he met a proper villain named Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, the leader of the thriving Gulf Cartel. In short order, Arturo Guzmán Decena, a highly-trained and ruthless member of the Mexican Army Special Forces, was in the drug lord’s employ.

The man had some curious motivations. Mexican cops and soldiers at the time often turned a blind eye to drug shipments in exchange for a little folding cash. In this case, however, Guzmán Decena went full Dark Side. While the money was way better, this also meant the hard young warrior embraced life as a hunted fugitive.

In retrospect, Mexico’s grinding slog toward democracy likely frightened him. With a true representative government came the real probability of accountability for all those sliced-off ears and noses. Guzmán Decena saw service with the cartels as the wave of the future.

Once Guzmán Decena had tasted the good life he made a few phone calls. Not long after, he had recruited 38 fellow Special Forces operators to make up his happy troupe. Each man was assigned a unique Z-number. Guzmán Decena was Z-1 or Zeta 1. This cadre of trained killers became Los Zetas.

It has been alleged that Guzmán Decena’s boss, Cárdenas Guillén, had the original idea. This is purportedly a transcript of a cell phone intercept made by the Mexican military that documents the birth of Los Zetas–

Cárdenas Guillén – “I want the best men. The best.”

Guzmán Decena – “What type of people do you need?”

Cárdenas Guillén – “The best-armed men that there are.”

Guzmán Decena – “These are only in the army.”

Cárdenas Guillén – “I want them.”

Absolute Power Corrupts Absolutely

Now that the Gulf Cartel had its own trained and equipped Specops unit, they exercised it. Z-1 and his troops collected outstanding debts, secured drug routes, and brutally exterminated the cartel’s enemies. They were fabulously successful. Cárdenas Guillén wielded his merry band of monsters to cement his grip on power.

Ángel Salvador Gómez Herrera was a close friend of Cárdenas Guillén. He had even been named godfather of Cárdenas Guillén’s child. However, in this rarefied world of high-stakes professional criminals, the line between friend and rival can be thin. Cárdenas Guillén suspected that Gómez Herrera was becoming covetous of his empire. That warranted a phone call to Z-1.

Immediately following the baptism of Cárdenas Guillén’s child, Gómez Herrera was invited to take a ride in the drug lord’s souped-up Dodge Durango. The newly-minted godfather sat in the passenger seat up front. Guzmán Decena had the seat behind him. The men exchanged laughs and basked in the moment following the infant’s baptism.

Then with little fanfare, Guzmán Decena drew his handgun and shot Gómez Herrera through the head. Mexican police later discovered his badly-decayed body discarded outside the town of Matamoros. In the aftermath of the execution, Guzmán Decena earned the nom de guerre “Mata Amigos” or “Friend Killer.” Apparently, he was good with that. The drug kingpin Cárdenas Guillén felt he had a buddy for life.

Eventually, Guzmán Decena and his fellow Special Forces operators came to appreciate that they really no longer needed the Gulf Cartel. They were accustomed to operating in hostile environments as a military unit and knew logistics, organization, and particularly extreme violence of action better than their soft decadent civilian bosses. As such Los Zetas took their show on the road.

In short order, the military-regimented Zetas displaced the Sinaloans as the largest drug cartel in Mexico. However, as Putin is discovering to his detriment in Ukraine, the challenge is not seizing power, it is keeping it. As the original Zetas were captured or killed by rival drug organizations and the Mexican government, their replacements were not cut from the same hard stuff. Regardless, for a time, Los Zetas was the dominant drug cartel in Mexico.

All Good Things Come to an End

The life of a successful drug lord is both stressful and fraught with peril. On November 22, 2002, Guzmán Decena was taking a meal with a few of his soldiers at a restaurant in Matamoros, Tamaulipas.

Feeling the need to unwind, he knocked back some Chivas and snorted a line of cocaine before heading over to the home of Ana Bertha González Lagunes, one of his several handy mistresses. She lived only a few blocks distant. Wishing his dalliance to be uninterrupted, Guzmán Decena had his troops seal off the roads leading into the area.

Guzmán Decena apparently got his quick roll in the hay, but the disruption to the community was substantial. A local denizen saw the commotion for what it was and notified the Mexican authorities. The cops notified the nearby Mexican Army quick reaction force who descended upon the woman’s house. They found Guzmán Decena duly distracted and gunned him down like a dog. He was 26 years old.

The Rest of the Story

Los Zetas did not take the execution of their flamboyant commander well. In the immediate aftermath, Zetas hitters kidnapped and murdered four members of the Office of the General Prosecutor near Reynosa, Tamaulipas. Mexican troops arrested Cárdenas Guillén, the head of the Gulf Cartel, in March of 2003.

The following year they bagged Z-2, Rogelio González Pizaña. Z-3, Heriberto Lazcano Lazcano, duly took his place. He fell in a shootout with the Mexican Navy in 2012. Chasing the Zetas was like playing Whack-a-Mole.

The gory death of Arturo Guzmán Decena was the first real blow that the Mexican government landed against Los Zetas. While the organization came back like a hydra, Guzmán Decena’s killing made a serious dent. This story is ultimately a great tale of Good Guys beating Bad Guys, but there yet remain persistent rumors that the ruthless SF operator-turned-drug lord was actually murdered by his own troops on the orders of his former mentor Osiel Cárdenas Guillén. For a proper king, maintaining one’s kingdom can indeed be a full-time job.

A fair amount of the original treasure that remained in the Batavia wreck has since been recovered. Photo by Guy de la Bedivere.

A fair amount of the original treasure that remained in the Batavia wreck has since been recovered. Photo by Guy de la Bedivere.