Hey I liked the picture and these folks bad as they were. They are some of the best Horse Soldiers ever to ride off to war. Grumpy

Hey I liked the picture and these folks bad as they were. They are some of the best Horse Soldiers ever to ride off to war. Grumpy

Situation: A known killer, armed with a lethal weapon, attempts to kill again. When lesser means fail, deadly force becomes the only remaining recourse.

Lesson: A violent criminal’s force must be met with necessary countervailing force. Reality does not dissuade false accusations in the aftermath. Truth and provable reality are the best antidotes to false accusations.

On a hot and steamy day, I stand in the middle of the death scene with defense attorney Rick Howard, fellow expert witness Steve Sager, and the cop who fired the fatal shots. We are in a ramshackle, now abandoned home that reeks of poverty, sadness and grief for lost loved ones. One of the plaintiff’s lawyers is there, too.

The room where it finally went down is smaller than it looked in the crime scene diagrams. I can see how close the three players in the deadly drama were to one another when the three gunshots exploded, which ended the crisis.

There were no winners on that painful day, only degrees of losing and suffering. Two law enforcement officers came close to dying and one violent man lost his life.

The officers now stood accused of wrongful death.

Welcome to America in the 2020s. I hate to write Ayoob Files without real names, and here I am doing it for the second time in a year at the request of legal counsel for the community that was sued over it. This case could have become a political football; it fortunately did not, and the town’s decision-makers do not wish to pick scabs off healing wounds. Accordingly, the only real names used here are the ones you have already seen. My apologies.

This took place in a hamlet in the Deep South. Its population is fewer than 2,000 and its police department consisted at the time of two men: the chief of police and a single patrolman. The average family income in the town was less than $20,000 per year, and predictably, the public safety budget was small. There was no money for body cameras or even a shotgun, let alone a patrol rifle. The town cops did carry pepper spray, though they couldn’t afford a TASER. At least they found money to purchase a modern duty sidearm: the 9mm SIG P320 with weapon-mounted light, loaded with 135-grain +P Hornady Critical Duty ammunition.

This purchase would prove to be a lifesaver.

In that sad home I described lived a man I’ll call Bad Son, a tall, lean man with a violent history. The home belonged to his mother, who had taken Bad Son in after he was released from prison.

The Mom had one Good Son who did his best to take care of her after she suffered a debilitating stroke. Unfortunately, she also had … the other son.

Local law enforcement was well aware that years before, Bad Son had shot and killed his mother’s boyfriend, and his defense lawyer was able to get him down to a manslaughter conviction, for which he had served hard time.

His Mom had forgiven him and taken him into her modest home. Her stroke had left her severely incapacitated, both cognitively challenged and with limited ability to speak. Good Son was doing his best to care for her.

The police, of course, were duty-bound to serve that warrant.

First Encounter

In mid-November of 2018, the entire Police Department — the chief of police and the one Patrolman — came to the home to serve the warrant. They had hoped to quietly take him into custody.

It was not to be. Bad Son confronted the officers with a large butcher knife and told the cops he wasn’t going to submit to arrest. As he came toward the two lawmen menacingly with the knife, the chief pepper-sprayed him.

The oleoresin capsicum had no effect whatsoever.

Their choice was now to traumatize the elderly, crippled mother by killing her son in front of her or retreating. Both policemen chose retreat, backing out of the house. Moments later, Bad Son fled out the back door and into the adjacent woods.

The decision was made to let him go. They would return later, having given Bad Son a chance to calm down and perhaps sober up.

That turned out to be a vain hope.

There was still an arrest warrant to serve. Hours later, with the Patrolman still on duty and the chief now off duty, Patrolman determined that Bad Son had returned home. He radioed for backup. In small communities such as this, the county sheriff’s department is often the only backup available for a lone municipal officer.

A full-time Deputy responded, as did a part-time deputy who knew Bad Son and hoped to be able to reason with him.

Serving their lawful warrant, the officers made entry. Good Son and the mother were both present. Fortunately, Good Son ushered his mother safely outside before things turned ugly.

Patrolman and Deputy moved carefully through the home, a “shotgun style” structure. They passed through the living room and into a hallway, which offered two portals into a small, narrow kitchen area.

Picture a flattened triangle. At the lower left corner is Deputy, near the first door leading into the kitchen. Ahead of him in the hallway, at the second door, is Patrolman. Inside that narrow kitchen is a doorway covered by a blanket, parallel to the doorway where Patrolman is standing.

And now, that blanket is swept away by an angry man’s arm and through the opening comes Bad Son, knife in hand, in an obvious state of rage and in a confrontational posture.

The tableau freezes into a momentary pause of movement. Patrolman, on the narrow end of the triangle and only a few feet away from Bad Son, takes him at gunpoint with his SIG P320. On Patrolman’s left, Deputy draws his department issue TASER and levels it on the knife-wielding Bad Son. They have flowed into the standard recommended pattern for dealing with an offender with a deadly contact weapon: one officer with the TASER, the other in the position of “lethal cover.” If the offender refuses to drop the knife, the one with the TASER will deploy that less-lethal weapon, and if the knife-wielder comes at either of them, the officer who is “lethal cover” must deploy lethal force.

They try to reason with him. They order Bad Son to drop the knife. Patrolman at one point pleads, “It doesn’t have to be like this!”

But Bad Son does not drop the knife. Accordingly, Deputy deploys the TASER.

The two probes lash out from the TASER, striking Bad Son. But before the 50,000 volts can take effect to fibrillate muscles and cause him to collapse, he simply sweeps the big knife down in an arc and severs the TASER wires.

Bad Son snarls, “I’ll kill you!”

And he lunges.

Patrolman had Bad Son already covered with his SIG extended at arm’s length in an Isosceles stance, and when Bad Son comes forward with the knife, Patrolman fires as fast as he can. The knife-wielder falls, and the cop stops firing.

And it is over. Bad Son lies motionless on the floor. He does not survive.

Neither officer has been touched by the big, deadly knife.

Gunfights generally end in seconds. Investigations thereof take months. The court aftermaths take years.

Larger, over-arching agencies generally perform the investigations of officer-involved shootings. This case was investigated by the State Department of Law Enforcement. It concluded the shooting death of Bad Son was justified under the circumstances.

The criminal justice community had cleared the police, but the civil justice side was still to be heard from. It is not much of an exaggeration to say, “anyone can sue anyone for anything.” We have to remember what you or I might recognize as complete and utter BS, when uttered by an attorney, becomes “plaintiff’s theory of the case” and has to be treated with the same serious respect as the actual truth. The wrongful death lawsuit by the estate of the late Bad Son against the town and the Patrolman was, in my opinion, a classic example.

Three shots had been fired. Bad Son had two gunshot wounds in the torso, one in the leg and one in the hand. The latter was a pass-through by a bullet that inflicted a secondary wound. It was the plaintiff’s claim that Patrolman had shot Bad Son in the leg, causing him to fall helplessly to the floor, and then pumped two unnecessary fatal bullets into the “victim.”

Fortunately, the defense was led by a lawyer particularly wise in these matters. Attorney Rick Howard meticulously crafted a defense that proved the truth of the matter.

Howard hired me as an expert witness. In turn, I recommended he hire Steve Sager to do a computer reconstruction showing the angles, the bullet trajectories, and the unforgiving timeline of what had happened. Sager and I had worked together on previous homicide cases, and his work had always been stellar. This case was no exception.

In matters like this, the defense strategy is two-pronged. First, take apart the false allegation brick by brick. Second, show the truth of the matter just as carefully in precise, documentable detail.

It was implied the officers had rushed in on Bad Son unnecessarily and used excessive force. The defense was able to prove otherwise. In the first encounter, the chief and the patrolman had actually retreated from the home rather than shoot the knife-wielding offender in front of his mother.

In the second and fatal encounter, Howard made it excruciatingly clear the officers had tried virtually all lesser force options, and Bad Son’s violent escalation had proven impervious to all of them.

Words had failed. Verbal crisis intervention is, in essence, reasoning with the suspect. As this case clearly demonstrates, one cannot reason with unreasonable people.

The pepper spray used by the chief had shown no effect. In the end, Bad Son had defeated the TASER with a slash of his 9″-blade knife. When he lunged with the edged weapon, his own actions had foreclosed any option the police had at their disposal except deadly force.

The plaintiffs implied the police should have just left Bad Son alone. Such a theory disregards the fact this man was known to have taken human life in the past and was furious at his crippled elderly mother and his brother for turning him in for stealing from his mom. Leaving him there with his family members — now potential victims — was not a good option.

Another implication was the old “he only had a knife, and the cops had bulletproof vests.” We were prepared to show a jury that the manufacturer of the officers’ body armor did not warrant it to stop a stabbing weapon. Steel is much harder than lead; knives are pointed, and bullets are blunt; and the long knife in the attacker’s hand had vastly more sectional density than the bullets the body armor was designed to stop. In any case, body armor covers no more than 30% of the body and does not shield the face, throat, etc.

One curse of explaining defensive shootings is they usually happen so fast the telling of what happened takes much longer than the incident itself. This can create the illusion it happened in slow motion, giving the participants all kinds of time to explore options. It is critical for the defense to constantly bring the triers of the facts back to the unforgiving speed of the attack and the limited time the defenders had in which to react.

Reconstruction showed Bad Son and Patrolman were perhaps six feet apart when the shots were fired. We were prepared to show that had Patrolman not pulled the trigger, he would have been stabbed or slashed in less than one second. We were also prepared to show the three shots in question were probably fired in no more than half of one second, from the first shot to the last.

The plaintiff’s theory rested largely on two witnesses: the reserve deputy and the owner of a funeral home who was offered as an expert witness for the theory of “shot in the leg and fell, then executed while helpless.” The latter theory was shown to be flatly impossible. Good Son, an earwitness who was outside when the shots were fired, reported a rapid-fire volley with no lapse between shots. So did everyone else, including the reserve deputy. This, plus the angles of the wound paths through Bad Son’s body, utterly destroyed the plaintiff’s theory. The plaintiff’s witness had no training in shooting reconstruction; I am guessing they offered him because no credentialed forensic pathologist or trained homicide investigator would support the alternate reality they were hoping to put before the Court.

In sworn pre-trial deposition testimony, the reserve deputy admitted the cops had tried to de-escalate, that Bad Son had finally lunged with the knife at close range, and the three shots had been extremely rapid. However, he averred he would have allowed Bad Son to stab him rather than shoot the man. Now, there’s a model of public safety for you: Let a convicted killer murder you, take your loaded service pistol and spare magazines from your corpse with which to kill the mother and brother who had turned him in and take the keys to your patrol car with privileged communications that would allow him to evade capture. To give you an idea of this witness’s expertise, when asked what sort of pistol he was issued, he did not know the model or even the make but thought it was a 9mm.

This travesty of a plaintiff’s case did not go to trial. On November 20, 2022, the Circuit Judge assigned to the matter dismissed the case in its entirety. The accusation that had hung over the cops for four years almost to the day was finally over.

Lessons

It is not an exaggeration to say you will be judged by the public for millions of times longer than it took for the shooting itself to take place. The knife-wielder’s lunge and the policeman’s three-shot volley clearly took place in less than one second. From that moment to the dismissal of the case four years later, some 126,144,000 of those seconds had elapsed.

If you want an attorney who knows how to handle this type of case, it won’t be cheap. Rick Howard’s orchestration of the defense and the successful motion to dismiss was nothing less than masterful. Howard himself told me later, “This would not have been possible but for an insurance company that believed the officers and gave them the best defense money could buy.” If you are a cop, join the union or fraternal organization that will pay for your defense in such a case. If you are a private citizen, join a post-self-defense support group such as Armed Citizens Legal Defense Network (ArmedCitizensNetwork.org) where (total disclosure) yours truly serves on the advisory board.

Finally, understand escalation and de-escalation of force as thoroughly as the two lawmen in this instance did. This case clearly shows why.

On 6 October 2024, the Wall Street Journal reported the sale of a large consignment of Russian AK74 assault rifles to the Houthi rebels in Yemen. Full auto AK74’s might seem like a pretty big deal on this side of the pond. In that part of the world, however, AKs are simply background clutter. If you want to make a splash in today’s news cycle, you’d best at least be peddling pilfered Novichok nerve agent or a few dozen man-portable surface-to-air missiles.

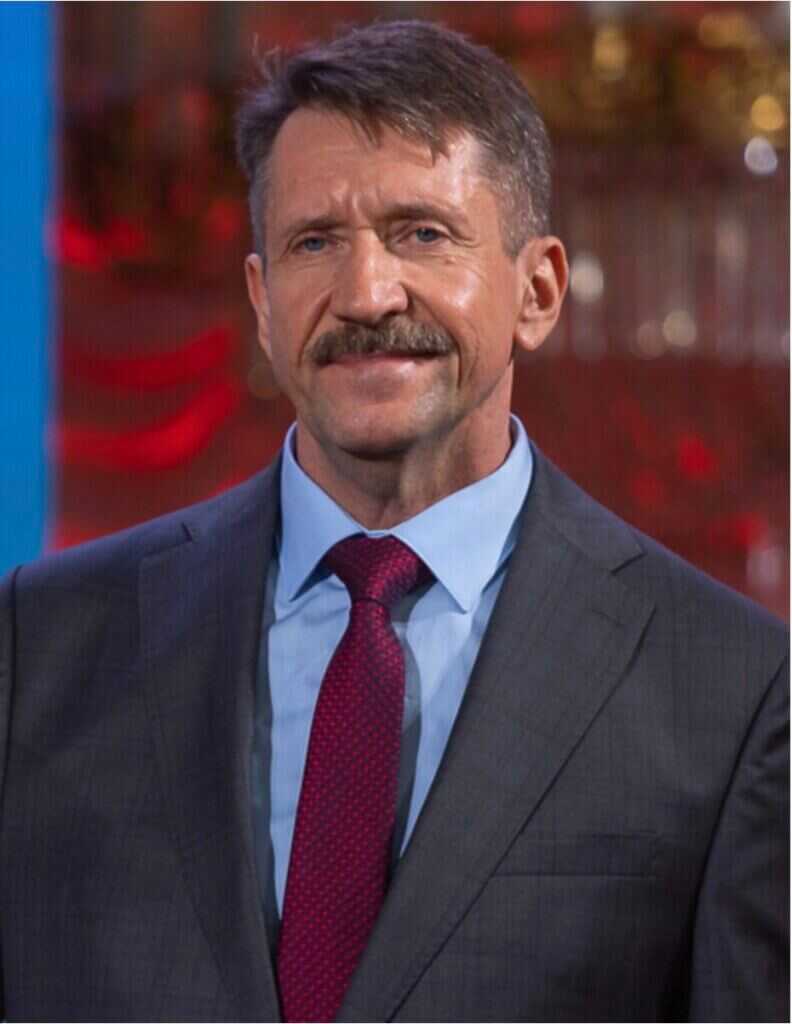

This is Viktor Bout, arguably the world’s most infamous illicit arms dealer. He has inspired a movie, done time in an American prison, armed half the planet, made about a zillion dollars, and been elected to public office in Russia. (Photo/Liberal Democratic Party of Russia)

This is Viktor Bout, arguably the world’s most infamous illicit arms dealer. He has inspired a movie, done time in an American prison, armed half the planet, made about a zillion dollars, and been elected to public office in Russia. (Photo/Liberal Democratic Party of Russia)

CJ Chivers made an exceptionally insightful observation in his seminal book, The Gun, about the history of the AK rifle (a truly great read, by the way). He said that you can tell a lot about a place by the price of a full-auto Kalashnikov assault rifle. If full auto AKs are ludicrously expensive or unobtainable, then settle down, buy a house, and enroll the kids in Little League. If you can trade into a GI AK for a healthy chicken and a couple of dog-eared copies of Hustler Magazine, then flee while you still can. Particularly in the less-respectable corners of Africa and the Middle East, AK rifles are like cell phones—everybody has one.

What caught my attention in this article was not that the Houthis were getting a bunch of sparkly new Kalashnikovs. It was Viktor Bout, the guy who brokered the sale. In certain circles, that guy is a legend.

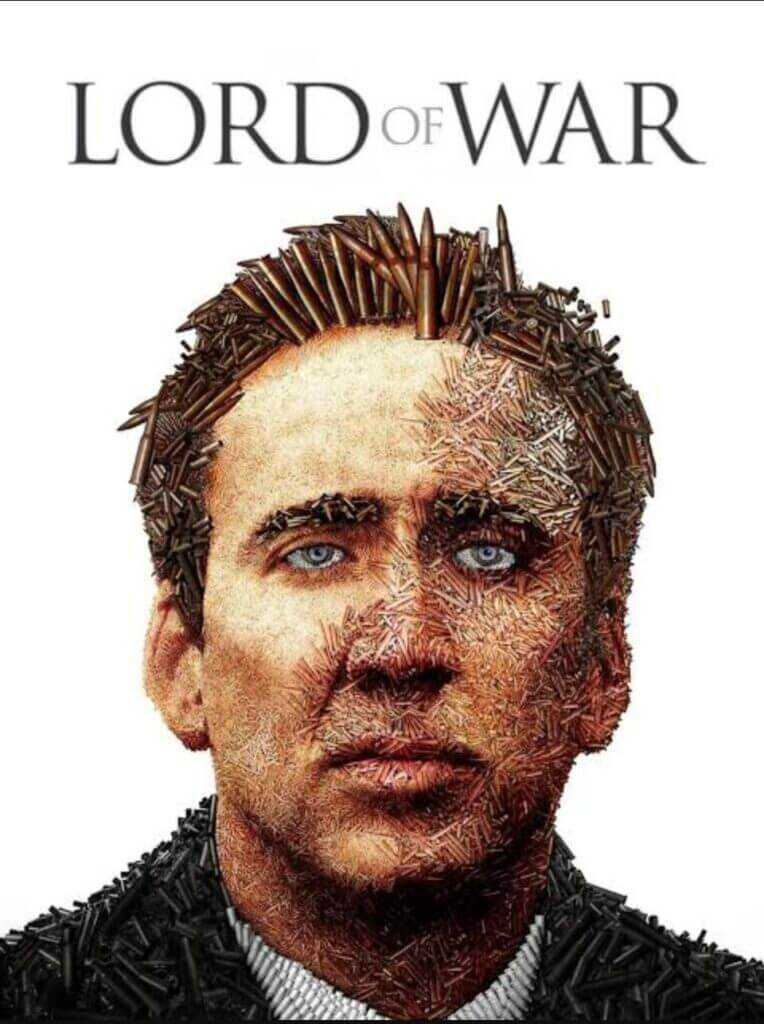

In 2005, Andrew Niccol released a film starring Nic Cage, Jared Leto, and Ethan Hawke titled Lord of War. The film carries a 62% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. It returned $72.6 million against a roughly $50 million investment.

However, don’t believe any of that. Lord of War was a simply magnificent movie. Second only to Raising Arizona, it was my favorite Nicolas Cage film ever. Cage’s character, a Ukrainian arms dealer named Yuri Orlov, was loosely based on Viktor Bout.

The filmmakers claimed that five different contemporary gun runners inspired Orlov. However, Bout tops that list. Bout was the original Merchant of Death.

Origin Story of Viktor Bout

Origin Story of Viktor BoutDespite our keeping Viktor Bout in an American federal prison for a decade, nobody is completely sure where he came from. The UN claims he was born in Dushanbe, Tajik SSR, Soviet Union, in January of 1967. He has an older brother named Sergei.

Following the implosion of the USSR in 1991, Bout obtained Russian citizenship. He has held at least four passports. Bout served in the Soviet military, but nobody knows in what capacity. He has a natural gift for languages. The man is fluent in English, French, Portuguese, Tajik, Farsi, Dari, Zulu, Xhosa, and Esperanto. He no doubt speaks Russian as well. Several of these languages he mastered while in prison.

Bout was alternately rumored to have been a Lieutenant Colonel in the Soviet Army, a Major in the GRU, a Soviet Air Force officer, and a KGB operative. Regardless, his facility with languages and natural audacity opened doors that would have otherwise remained closed. Viktor Bout is what happens when you are really smart, pathologically driven, and born without an operational conscience.

Soviet military service took Bout to Angola in the 1980’s. That’s where he learned Zulu and Xhosa. While in Africa, he discovered that there was money to be made in transporting and selling weapons. Once the Iron Curtain fell, Bout left the military and bought himself some airplanes.

His first purchase was three Soviet-surplus Antonov An-12 cargo planes. The days immediately following the dissolution of the Soviet Union were the Wild West in that part of the world. The central government had essentially evaporated, and local military commanders found themselves in possession of truly vast amounts of military equipment. They sold much of that to anyone with cash. Bout scared up a little folding money and stepped into that vacuum to find a buyer’s market. With product to move, Bout struck out across Africa peddling his wares.

Those first three Antonov An-12s were soon joined by four An-8s as well as an unknown number of massive Il-76 jet-powered cargo planes. At the apogee of his enterprise, he owned and operated some sixty aircraft and employed 300 people. Bout used these planes to move weapons and ammunition to anyone with money.

For a really smart guy who was not afraid of the law, the world was his oyster. As an example, Bout forged end-user certificates purportedly for Togo and used them to avail himself of vast numbers of Bulgarian automatic weapons. He then flew these guns down to Africa and armed anyone who could afford to take his calls. In many cases, Bout sold weapons to both sides of a conflict.

Bout’s client list sounds like the guest register at a psychopath convention. He stepped into the power vacuum in Libya after the death of Gaddafi in 2011 and quite literally made a killing. Bout was spotted in Teheran chatting up the mullahs. He made regular sorties into Afghanistan, but he always claimed to be selling to the Northern Alliance rather than the Taliban. However, consider the source. I’d be willing to bet he lies a lot.

Bout sold guns to Bosnian government forces during the violent deconstruction of Yugoslavia. His airplanes were used to move weapons under a falsified Zairean end-user certificate into nearby Angola to equip the UNITA savages operating there. Bout helped arm Hezbollah in the lead-up to their 2006 war with Israel. He also moved quite a lot of merchandise to Charles Taylor’s mini-monster child soldiers in Liberia. Along the way, Bout did business with almost everybody, including the United States. He supposedly made $60 million off of Uncle Sam by flying equipment into Iraq in support of Coalition operations there.

It’s not possible to sell that many guns without getting your hands bloody. Laundering the proceeds of that enterprise took talent. Though he did, miraculously, avoid getting slaughtered by some agitated warlord someplace, Bout eventually ended up on the radar of the American Justice Department.

In addition to his natural proclivity for languages, Viktor Bout has a criminal’s mind. He moved constantly, shifted assets between companies, some more legitimate than others, and re-registered his airplanes as needed to deflect attention from what they were being used for. Along the way, he lived in such disparate places as Russia, Rwanda, South Africa, Syria, the UAE, Belgium, and Lebanon.

Believe it or not, the guy is married. He met his wife Alla Vladimirovna Bout in 1980 in Mozambique. Their daughter Yelizaveta was born 14 years later.

I’ve been married for 37 years myself. My wife is sweet, smart, and devoted. That woman would have justifiably dumped me like a dirty shirt had I dragged our family all over the world running guns and fleeing Interpol.

In 2008, the US government paid an informer to contact Bout claiming to be a representative of the Colombian communist rebel group FARC. FARC is a mob of Marxist-Leninist lunatics who have terrorized Colombia since 1964. This informant engaged Bout to deliver 100 9K38 Igla surface-to-air missiles along with a buttload of anti-armor weapons via parachute to pre-arranged locations in the Colombian jungle. When Bout flew to Thailand to close the deal, he was met by Thai law enforcement officers on the strength of an Interpol Red Notice initiated by the Americans.

As I said, Viktor Bout is a smart guy. He deftly dragged his feet through the Thai legal system, delaying his final extradition to the US until 2010. On 2 November 2011, Bout was convicted of a wide variety of charges including conspiracy to kill Americans, wire fraud, money laundering, and illegally purchasing airplanes. He was sentenced to 25 years in federal prison.

The following year, Bout was interviewed for the New Yorker. He said, “They will try to lock me up for life. But I’ll get back to Russia. I don’t know when. But I’m still young. Your empire will collapse and I’ll get out of here.” He also claimed that, if the same standards were applied across the board, every American gun shop owner would be in prison.

And so things remained…for a decade. Despite being represented by the law firm of former US Attorney General John Ashcroft, Bout lost his various appeals. He had his legal fees paid by Pravfond, a sleeper organization funded by the Kremlin. Throughout it all, he took his mail at the federal penitentiary in Marion, Illinois.

And then WNBA star Britney Griner was apprehended at the Sheremetyevo International Airport in Moscow with less than a gram of hashish oil in a vape pen. That insanely stupid faux pas earned her a $16,301 fine and nine years in a Russian prison. The typical sentence for a Russian citizen caught with the same stuff is fifteen days.

Griner quite vocally hates America. She once said, “I honestly feel we should not play the national anthem during our season. I think we should take that much of a stand.”

Eventually, President Biden struck a bargain with Putin to trade the ungrateful basketball activist with the vape pen weed even-steven for Viktor Bout, the Merchant of Death. The original proposal was going to include US Marine Corps veteran Paul Whelan as well, but he got negotiated out of the deal. Whelan was serving sixteen years on a trumped-up charge of espionage. Whelan did eventually gain his freedom some 18 months later as part of another fairly one-sided exchange.

Viktor Bout returned home to a hero’s welcome. He voiced support for the invasion of Ukraine and promptly entered politics, winning a seat in the Legislative Assembly of Ulyanovsk Oblast. Now he also appears to be hawking AK74 rifles to the Houthis in his spare time.

Viktor Bout is a weird guy. A vegetarian atheist who claims to share views with Jesus, Krishna, Buddha, and Zarathustra, Bout thrives in the darkest corners of the Information Age. Driven, connected, amoral, and brilliant, Viktor Bout seems an interesting swap for a dope-smoking, America-hating, LGBT-activist basketball player. Personally, I think Joe Biden might have gotten played.