Category: Dear Grumpy Advice on Teaching in Today’s Classroom

Can you imagine the noise this soldier must of made just by walking his post in 14th century BC!?! Grumpy

Wheels, law codes, literature, beer, and now soap – ancient Mesopotamia was the origin-place of all these inventions, thus covering crucial avenues from transportation, society, and culture to health. As for the latter-mentioned ‘product’, the history of soap, unlike its function of cleaning, is a bit murky. According to most scholars, the first evidence of a soap-like substance harks back to 2800 BC.

But confusion arises when it comes to this substance’s original inventor, with some sources pointing towards the ancient Babylonians. But historically, Babylonia as a political entity emerged several centuries after the stated date. So we must attribute the honor of inventing soap to their culturally-linked brethren – the Sumerians, who held sway over Mesopotamia for most of the 3rd millennium BC.

The Oldest Soaps

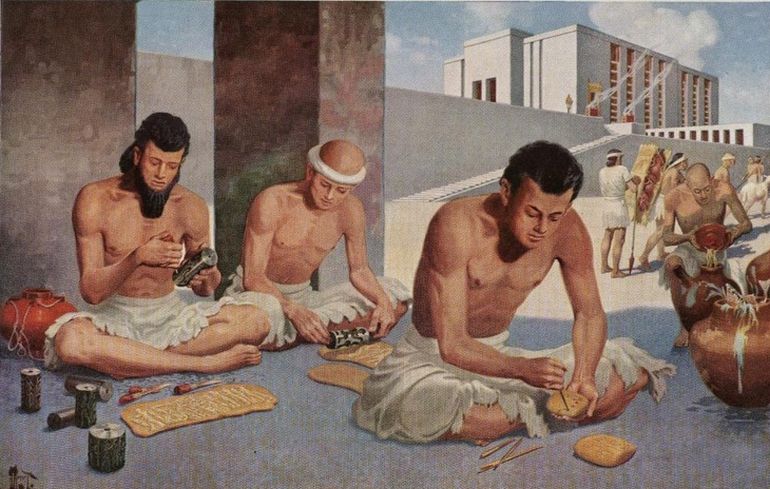

In any case, what we know is that the precursor to soap was made by mixing animal fats with wood ash and water. As for its functionality, the ancient Mesopotamian people probably used their concocted cleaning products for washing wool used in textiles.

The oldest ‘soaps’ were also used for ritualistic purposes by Sumerian priests when they purified themselves before sacred rites. And in later years, some of the modified versions were possibly even used for treating skin diseases.

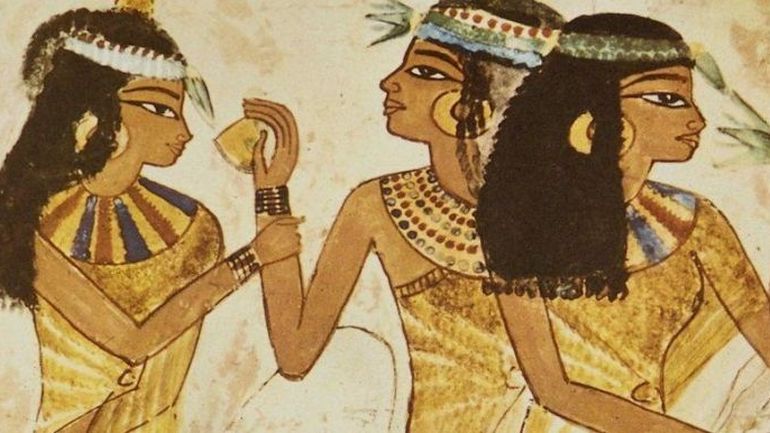

Given these variant modes of use, it comes as no surprise that a few Mesopotamian tablets even make mention of the different methods for making soap in the pictorial cuneiform script. The ancient Egyptians also devised techniques (circa 1500 BC) for concocting soap-like components, by mixing alkaline salts with oil – as evidenced by a few papyrus specimens.

Moreover, the Neo-Babylonians further enhanced the recipe of ‘stone-washing’ soaps, by effectively incorporating ashes, cypress extracts, and sesame oil, during the 6th century BC.

The Roman Era

Pliny the Elder’s Historia Naturalis encyclopedia (written circa 77 AD) mentions the term sapo, the Latin word for soap. The naturalist goes on to explain how sapo was manufactured from a combination of tallow and ashes and was primarily used as a waxy substance for hair.

The ancient Roman author also talked about how the product was used more by the Gaulish and Germanic men rather than Romans – with the latter preferring to scrap their skins clean by using essential oils, white sand (as abrasive), and strigil (a tool for scraping off dirt and sweat).

Galen, the prominent 2nd century AD Greek physician and surgeon who practiced in the Roman empire, further mentioned how soap was made by using lye while prescribing their effectiveness in cleaning away impurities from both body and clothes. He also described how the best soapy products of his era were of Germanic and Gaulish origin.

Medieval Times

Like many developed habits, the scope of using soaps fell drastically after the decline of the Roman Empire, circa 5th century AD. In some cases, church institutions across Europe actively discouraged the use of soap and even the act of bathing itself, since they were allegedly linked to the pagan ways of the earlier empire.

However, by the 6th century AD, there were a few emerging soap-making guilds in mainland Italy. And by Charlemagne’s reign, circa 8th century AD, soaps were considered as being one of the grooming products preferred by the nobles of royal estates.

Interestingly enough, as opposed to popular notions, Vikings were also known to use a very strong lye-based soap. However, these soaps possibly had greater socio-cultural purposes beyond just cleanliness – since the lye was used for bleaching their beards. In other words, Vikings preferred to be blonds with lighter-complexioned facial hair.

On the other hand, the cultural flowering of medieval Islamic realms brought forth their hygiene-based practices, including the use of soaps. In fact, the Syrian city of Aleppo had a tradition of manufacturing high-quality soaps since ancient times (as a legacy of Mesopotamian culture).

Over time the scope translated into a medieval industry with merchant families plying their trades over generations that entailed the production and distribution of soaps, in some part fueled by the Silk Route.

By the 11th century AD, many Crusaders were enamored of the ‘exotic’ hygiene products, and as such brought forth some of the Aleppo recipes to European realms. During contemporary times, much of Spain was also under the rule of Muslim Moors, and the resulting cultural association made the peninsula one of the leading manufacturers of the famed olive oil-based Castile soaps.

The techniques of soap-making gradually also spread to England by the 13th century, where it was made from wood ash; and to France by the 14th century, where the renowned Marseille soap (made by combining seawater, ash, and olive oil) catered to the nobility.

Modern Epoch

It should however be noted that in spite of the ever-evolving soap-making techniques over the millenniums, before the 18th century, the usage and manufacturing of soap still remained relatively small-scale when compared to the population.

Simply put, the users of soap tended to be wealthy because of the high-cost factor required to procure the products. Moreover, due to the prevalence of ‘bothersome’ ingredients (like animal fat), many of the soap varieties gave off their unpleasant aroma.

But with the advent of the industrial revolution, chemists were able to incorporate aromatic substances like palm oil and coconut essence – mostly imported from Asia and Africa, into soap products. And intriguingly enough, by the 19th century, it was a war that rather instigated the mass-scale use of soaps.

This is because during the Crimean War fought in 1854-1857, the British forces suffered many of their casualties from widespread diseases, as opposed to just battlefield wounds. Such adverse conditions fueled the adoption of hygiene regulations for modern armies, thus leading to the practice of regular usage of soaps by soldiers, who in turn brought their healthy habits home.

And by the early 20th century, soap finally made its debut as a mass-consumed commercial product, thanks to the massive marketing efforts put forth by Proctor & Gamble (P&G). As a matter of fact, P&G spent more than $400,000 a year (equivalent of over $10 million in current valuation) during the early 1900s – so much so that the radio serials were to known as the ‘Soap Operas’ because of the profitable sponsorship of the soap manufacturers.

The Palazzo Grimani, Venice, Italy.