Category: Allies

Sunday Shoot-a-Round # 306

Introduction to the Baker Rifle

In the annals of military history, few weapons have earned a reputation as fearsome as the Baker Rifle. Crafted with meticulous precision and boasting remarkable accuracy, this firearm emerged as a game-changer during the Napoleonic Wars.

Like a maestro wielding his baton, the Baker Rifle conductor transformed the art of warfare, leaving an indelible mark on the battlefield. Join us as we delve into the compelling tale of this remarkable weapon, its evolution, and its unparalleled impact.

A Legacy of Innovation

In the early 19th century, the British Army faced a daunting challenge. The traditional smoothbore musket, while effective at short ranges, proved ineffective against the French forces led by Napoleon Bonaparte. Recognizing the need for a revolutionary weapon, Captain Ezekiel Baker of the 95th Regiment of Foot set out to engineer a firearm that would redefine long-range combat.

Baker’s stroke of genius lay in his design of a rifled barrel, which introduced spiral grooves inside the bore to impart a stabilizing spin on the bullet. This innovation drastically improved accuracy and extended effective range, setting the stage for a transformation in battlefield tactics.

A Weapon of Exceptional Precision

The Baker Rifle, also known as the Pattern 1800 Infantry Rifle, boasted a .625-caliber barrel that measured 30 inches in length. With its smoothbore muzzle, the weapon featured a unique three-groove rifling pattern with a 1:66 twist rate. This rifling gave the bullet a stabilizing spin as it left the barrel, greatly enhancing accuracy over longer ranges, up to 200-300 yards, as opposed to the typical 50-100 yards of a smoothbore musket.

The Baker Rifle’s flintlock ignition system, though slower than the newer percussion cap system, added an air of reliability to the weapon. With a rate of fire of approximately three rounds per minute, the rifle required well-trained marksmen who could handle the complex loading process. However, the disciplined 95th Rifles, renowned for their expert marksmanship, proved the perfect candidates to wield this masterpiece.

The Baker Rifle was also lighter and shorter than the typical infantry musket, making it easier to handle, especially in rough terrain or in the skirmishing role that the rifle regiments were often assigned to. The rifle was equipped with a sword bayonet, a response to the shorter reach of the weapon compared to a musket with a traditional bayonet.

Battlefield Impact

The Baker Rifle first made its mark during the Peninsular War (1808-1814), where the British Army faced off against Napoleon’s forces on the Iberian Peninsula. The rifle’s exceptional accuracy and extended range provided British skirmishers, notably the famous “Riflemen” of the 95th Regiment, a significant advantage over their French counterparts.

The Baker Rifle’s ability to engage targets accurately at ranges of up to 200 yards, almost double the effective range of the smoothbore musket, revolutionized military tactics. British riflemen targeted enemy officers and artillery crews, sowing confusion and destabilizing enemy lines. This targeted approach disrupted Napoleon’s famed columns and changed the face of warfare.

The most notable users of the Baker Rifle were the 95th Regiment and the 5th Battalion, 60th Regiment of the British Army, famously known as the “Green Jackets”. These Riflemen, as they were known, were specially trained in light infantry tactics and marksmanship, with an emphasis on individual initiative and self-reliance. This contrasted with the massed, close-order tactics and volley fire of the regular infantry.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Baker Rifle proved instrumental in a number of key battles. At the Battle of Vimeiro (1808) and the Battle of Corunna (1809) during the Peninsular War, the riflemen were successful in skirmishing ahead of the main British lines, disrupting French movements and causing significant casualties. Later, at the Battle of Waterloo (1815), the Rifle regiments used their precision weapons to good effect, targeting French officers and artillery crews, creating confusion and turning back the French attacks.

However, the Baker Rifle was not without its drawbacks which led to unique tactics to compensate for it’s shortcomings. It was slower to load than a smoothbore musket due to the tighter fit of the bullet in the rifled barrel, which could be a disadvantage in the face of a rapid enemy advance. The Rifle regiments were thus often used in conjunction with regular infantry, whose volleys could hold the enemy at bay while the riflemen picked off targets.

The Legacy Continues

While the Baker Rifle left an indelible imprint on the battlefield, it eventually made way for more modern firearms. The advent of the percussion cap system and the rifled musket, such as the famous British Enfield Rifle, signaled the end of the Baker’s era. However, its legacy as a harbinger of precision and accuracy lived on.

The Baker Rifle’s impact extended far beyond its service years. Its technological innovations influenced the development of subsequent rifles, ultimately shaping the course of firearms design. The quest for greater accuracy and longer effective range echoed throughout the ages, leading to the creation of some of the most iconic rifles in history.

Conclusion

The Baker Rifle, born from the visionary mind of Captain Ezekiel Baker, carved a unique path through the annals of military history. With its exceptional accuracy and extended range, this innovative firearm revolutionized the art of warfare during the Napoleonic Wars. As the British Army’s answer to Napoleon’s might, the Baker

Rifle set new standards for precision and lethality. Though its service years were limited, its influence continues to reverberate, forever etching its name in the pantheon of legendary weapons.

12 Gauge Pump and Semi Explained

Lt. Mikhail Petrovich Devyatayev was a Russian P-39 Airacobra pilot during World War II. The peculiar mid-engine P-39 offered fairly poor high-altitude performance and was subsequently relegated to second-line duties by the US Army Air Corps.

Lt. Mikhail Petrovich Devyatayev was a Russian P-39 Airacobra pilot during World War II. The peculiar mid-engine P-39 offered fairly poor high-altitude performance and was subsequently relegated to second-line duties by the US Army Air Corps.

However, the Russians desperately needed a nimble ground attack plane. The massive 37mm cannon that fired through the Airacobra’s propeller hub was just the ticket. The Soviets gratefully received 4,773 of the little planes under Lend-Lease.

Lt. Devyatayev had a successful combat career. He flew some 180 combat missions during the war, downing a Stuka dive bomber as well as an Fw 190 in the process. However, in the summer of 1944, his luck ran out. Shot down near Lviv, Ukraine, Devyatayev was taken prisoner by the Germans.

A Hard, Brutal World

Life on the Western Front during World War II was horrible. The fight between the Germans and the Russians in the East was absolutely feral. The Western Front was a fight for domination. The Eastern Front was a fight for extermination. At 27 years of age, Lt. Devyatayev ended up in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Had the Germans in the camp discovered that Devyatayev was a fighter pilot, they would have killed him outright. As a result, the resourceful young flyer took the identity of a Soviet infantryman who died in the camp and successfully passed himself off as a conscript. In this capacity, he was shipped to Peenemünde to work as slave labor building V2 missiles for the Germans.

Administered by the SS, the German slave labor program consumed millions of lives. Russian POWs were maintained on starvation rations and then worked until they died. Realizing that he and his mates were doomed if they didn’t do something drastic, Devyatayev began actively looking for a way out. He found it at an airfield adjacent to their work site.

Their Ticket Home

The Luftwaffe flew Heinkel He 111 bombers out of the nearby airfield. Lt. Devyatayev had never flown a twin-engine bomber and had never seen the inside of a He 111. However, one day when the sentries broke for lunch, Devyatayev and a handful of his mates killed a German guard with a sharpened crowbar and stole his uniform.

One of the Russians then donned the dead man’s bloody clothes and proceeded to march his fellow prisoners across the tarmac. The Luftwaffe ground crewmen took little notice.

The first He 111 they came to was locked and had no batteries. Devyatayev and his friends pried the door open while one of their group secured a ground power unit. In the process, they encountered another small group of Russians and invited them to come along. With a total of 10 Russian POWs packed into the plane, Lt. Devyatayev got busy.

The desperate Russian aviator did get the big plane cranked, but he had no idea what he was doing. He inadvertently spun the aircraft around the parking apron before getting it roughly pointed in a takeoff direction. On his first attempt, he failed to attain flying speed and had to abort. Snapping the big plane around, he tried again and finally broke ground.

Devyatayev successfully avoided a Ju 88 launched to intercept them, as well as Russian fighters they encountered en route. Upon landing in Russian-held territory, Devyatayev and his men were arrested as traitors by the NKVD. When they related all they knew about the V2 program, they were eventually released.

Lt. Devyatayev was finally recognized as a Hero of the Soviet Union in 1957. He died in 2002 at age 86. The German medium bomber that spirited him and his buddies to safety formed the backbone of the Luftwaffe’s bomber fleet early in the war.

The Machine

The He 111 was originally designed in 1934 nominally as a fast airliner. The Germans were still pretending to be constrained by the Versailles Treaty, which ended World War I and restricted their military aspirations. However, the sleek, fast, twin-engine Heinkel was clearly a warplane. What had begun as a mandate to create the world’s fastest passenger airplane soon morphed into an overtly military project.

The twin-engine He 111 evolved from the single-engine Heinkel He 70 Blitz (Lightning). The He 70 was also considered a passenger aircraft. Powered by a 599-horsepower BMW VI engine, the He 70 would carry four passengers and sported a maximum speed of 240 mph. The He 70 pioneered the characteristic elliptical wing that was eventually used in the larger He 111.

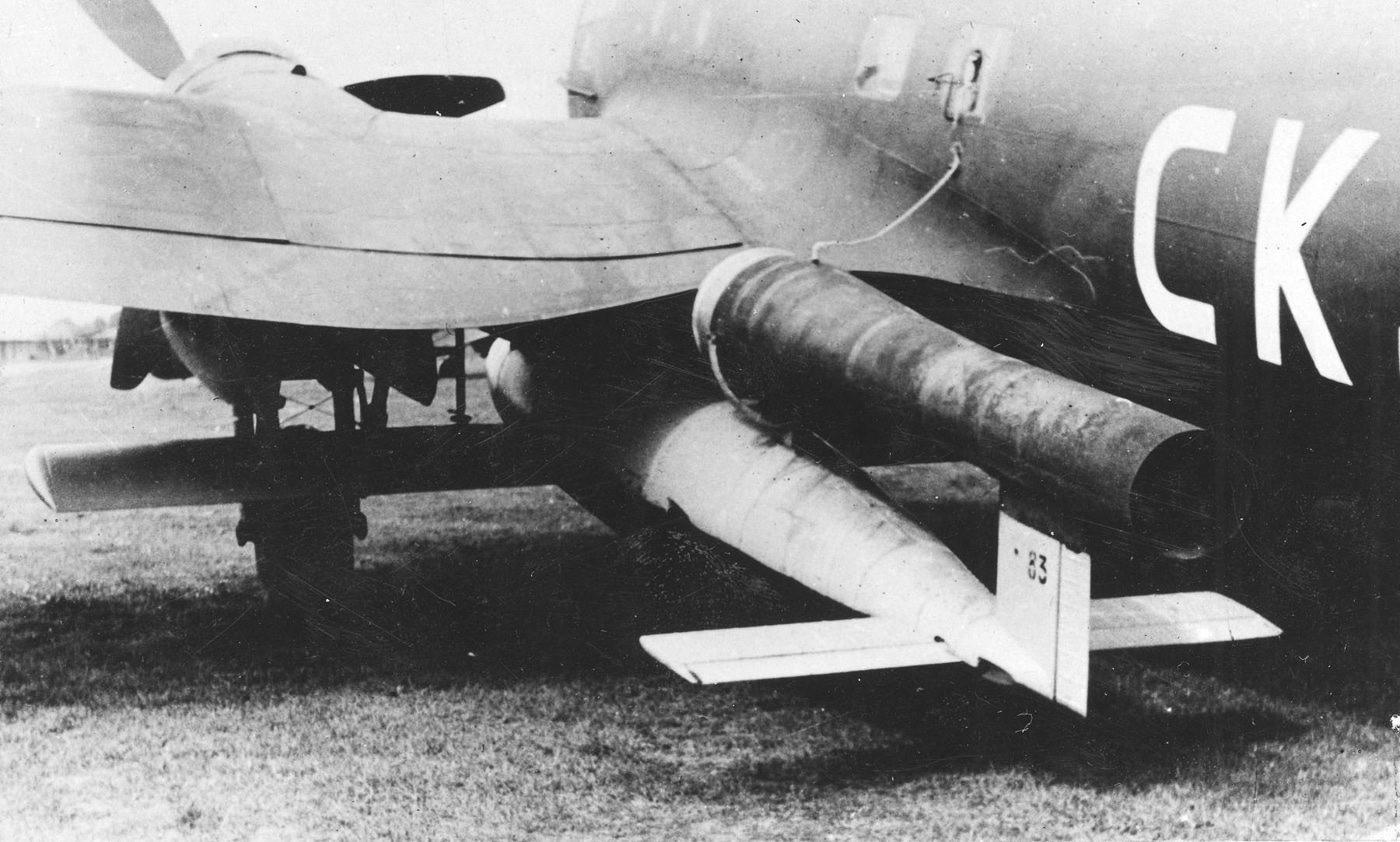

The He 111 was a fairly big machine. With an overall length of 57 feet and a wingspan of 74 feet, the production version of the He 111 packed as many as seven 7.92mm machineguns and 4,400 pounds of bombs internally. A further 7,900 pounds’ worth of bombs could be included on external racks. However, when fully loaded, the He 111 typically required rocket-assisted takeoff units to get aloft.

Details

The He 111 sported a fairly unconventional layout. The He 111 was a single-pilot airplane with the pilot sitting on the left per custom. The corresponding right seat was reserved for the bombardier/navigator.

This crewman was expected to leave his seat and slide forward into the nose when it was time to drop ordnance. The control column was arranged on a pivoting mount that could be rotated over to the navigator position in the event the pilot was incapacitated. Three other crewmembers operated the radios and defensive machine guns.

The wide, glazed nose offered superb visibility…under certain circumstances. The pilot’s position had no floor so as to provide an unobstructed view. The rudder pedals were mounted on arms so the pilot could see the terrain below.

The engine controls were mounted above the pilot’s head, also to keep them out of the way. All that was great, but the rounded Plexiglas panels glared badly in bright sunshine. Some of the bottom transparent sections were removable so as to allow rapid egress in an emergency.

Bombs rode in the bomb bay in magazines held vertically nose up. This made them easy to load and maximized space in the streamlined fuselage. Once deployed, the slipstream caught the tail fins on these devices and upended them in short order. He 111s were fitted with a variety of different defensive armament options during the course of the plane’s operational history.

Variations

Most He 111 planes were used as medium bombers. In this capacity, the He 111 played an outsized role in pummeling the UK during the Battle of Britain. However, this workhorse of an airplane did a lot of other stuff as well.

The He 111 was adapted to deliver aerial torpedoes for use in the North Atlantic. The plane was also used to emplace sea mines from the air. Experiments were undertaken using the He 111 to launch V1 buzz bombs in-flight as well.

The Germans developed a truly bizarre version of the He 111 called the He 111Z Zwilling (“Twin”), in which two standard fuselages were mated along a common central wing section. The resulting plane carried five engines and was used as a tow aircraft for the massive Me 321 glider. The single set of pilot’s controls was located in the port-side fuselage. Despite the bodged-together nature of the design, the pilots who flew these machines said they were a dream in the air.

Ruminations

A total of 6,508 Heinkel He 111 planes rolled off the assembly lines before production was curtailed in 1944. By then, the He 111 was badly obsolete. As a result, the plane was used primarily for transport duties until the end of the war. In a world liberally populated with Mustangs, Thunderbolts, Typhoons, Spitfires, and Lightnings, the lumbering He 111 was easy meat.

Of those 6,508 machines, five German versions and twelve Spanish-built Casa copies survive today. None of them are flyable. The classic 1969 British war film Battle of Britain has some awesome aerial footage of these Spanish He 111 copies in action.

Sleek, cool, rugged, and versatile, the He 111 served the Luftwaffe on all combat fronts during WWII. It was also adequate to spirit 10 resourceful Russians away from their slave labor camp and almost certain death. In so doing, the Heinkel He 111 became an iconic part of World War II history.