Have I made myself perfectly clear?

| June 6, 2012

Gun Skills & Safety, Manly Skills, Survival, Tactical Skills

Recently I’ve had the itch to buy a shotgun. It started after I read Creek’s post on how to build a survival shotgun. The itch only grew stronger after I became a homeowner (I kind of feel like Kevin McAllister). The shotgun is the perfect weapon for home defense and disaster prep. It’s powerful, reliable, and versatile. You can use it to fend off home intruders, hunt for food, or even shoot skeet with your buds.

But as I’ve discussed before on the site, I’m a complete novice when it comes to guns. I grew up around them, but I just didn’t take an interest in them until recently. Before I brought a shotgun into my house, I wanted make sure I knew how it worked and how to fire it safely and correctly.

So I headed over to the U.S. Shooting Academy here in Tulsa, OK to talk to Mike Seeklander, President of the Academy and co-host of Outdoor Channel’s The Best Defense. Mike’s helped me out before with articles on how to fire a handgun and a rifle. On this trip, he explained the very basics of understanding and firing a shotgun. Today I’ll share what I learned from Mike for those folks out there who are also interested in becoming first-time shotgun owners.

Mike’s pump-action and semi-automatic shotguns

Shotguns are fired from the shoulder and are typically used to hit targets at shortdistances. Unlike rifle and handgun cartridges that can only fire a single projectile, a shotgun cartridge typically fires multiple pellets called “shot” that spread out as they leave the shotgun’s barrel. Because the power of a single cartridge charge is divided among multiple pieces of shot, the energy of the shot decreases greatly as it travels away from the gun. That’s why shotguns are short-range weapons.

There are a variety of shotguns out on the market that serve different purposes. Below we highlight the most common types.

Break-action shotguns. Break-action shotguns have a hinge between the barrel and the stock that allows you to “break” or open the barrel to expose the breech in order to load your ammo. If you’ve ever seen pictures of old big game hunters or cowboys holding a shotgun, they were probably holding a break-action shotgun. Break-action shotguns are usually double-barreled, with the barrels either side-by-side or placed one on top of the other. They’re typically used by hunters and sport shooters. The big disadvantage of break-action shotguns is that they’re single shot guns, meaning once you fire the single round in each barrel, you have to reload.

Mossberg 500 pump-action shotgun

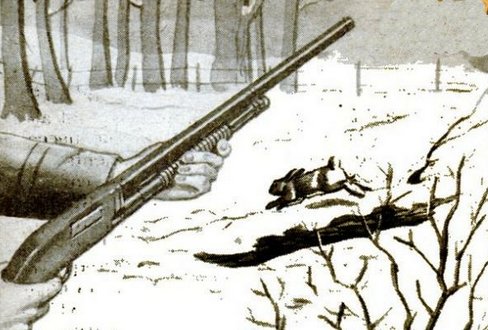

Pump-action shotguns. A pump-action shotgun is a single-barrel shotgun that holds multiple rounds (unlike break-action shotguns). The way you extract spent shells and chamber a fresh round is by pulling a pump handle towards yourself, and then pushing it back into its original position along the barrel. Pump-action shotguns are widely used by police forces around the world because of their reliability and ability to hold multiple rounds. The Remington 870 has been the standby shotgun for American police forces for years, while the U.S. military has been partial to the Mossberg 500.

The general consensus in the firearms community is that pump-action shotguns are the top choice for home defense. They’re relatively easy to use, nearly impossible to break, and are super reliable. More importantly, the sound of chambering a hot round into a pump-action 12 gauge is sure to soil the britches of even the most hardened criminal. As an added bonus, they’re relatively cheap, with prices beginning around $200.

One of the things you have to watch out for when firing a pump-action shotgun is short-stroking. That’s when you don’t push the pump all the way back to its original position, resulting in a failure to chamber the next round in the magazine.

Browning semi-automatic shotgun

Semi-automatic shotguns. A semi-automatic shotgun fires a single shell each time the trigger is pulled, automatically ejects the spent shell, and automatically chambers a new shell from a magazine. This allows you to fire off shots quickly. Some states ban hunting with semi-automatic shotguns, so be aware of that if you plan on using your gun to hunt.

Because rounds are automatically loaded and the design is more complex, semi-automatic shotguns are more prone to jamming failures than pump-action or break-action shotguns.

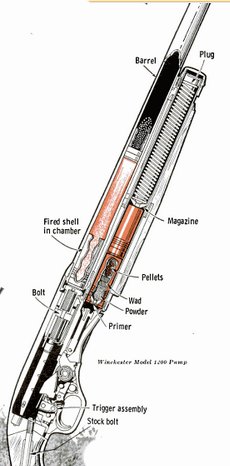

Diagram of a shotgun

Shotgun ammo is broken down into three categories: birdshot, buckshot, and slugs.

Birdshot. Birdshot is smaller than buckshot and is used primarily for hunting, you guessed it, birds. Birdshot size is categorized by a number: the larger the number, the smaller the shot. The smallest birdshot is #12 shot and the largest is size FF. All birdshot pellets have a diameter smaller than 5 mm. Birdshot is so small it’s simply poured into a shotgun shell until the shell reaches a certain weight.

Buckshot. Buckshot is typically used for hunting small to medium-sized game and for police and home defense purposes. As with birdshot, the buckshot is categorized by a number that decreases as the size of the shot goes up. The smallest buckshot is #4 and from there the sizes go past #1 to 0000 (quad-ought), 000 (triple-ought), 00 (double-ought), and 0 (ought). Unlike birdshot, buckshot is too large to be poured into a cartridge. Rather, the buckshot pellets are stacked into the shell in a fixed geometric arrangement in order to fit.

Slugs. Slugs are basically a giant bullet. Instead of firing multiple pellets, a shotgun shell with a slug in it only fires a single slug. Slugs are primarily used to hunt large game and for military and police purposes. Slugs are rifled which gives them spin as they leave the barrel of the gun, making the slug much more accurate and stable in flight.

Gauge

Unlike handguns and rifles that use caliber to measure the diameter of the barrel, shotguns use gauge. Measuring gauge goes back to the days of muzzle-loading guns. A shotgun’s gauge number is determined by the number of lead balls that are the size of the gun bore’s diameter that can roll down the gun’s barrel to make a pound. So for example, in a 12 gauge shotgun, twelve lead balls with a diameter equal to the diameter of the barrel adds up to one pound.

Confused? Don’t worry. It takes a bit to wrap your head around it. Just remember this: The smaller the shotgun gauge number, the larger the barrel; the larger the barrel, the bigger the boom from your boomstick.

The most common shotgun gauge sizes are: 10 gauge = .775 inch, 12 gauge = .729 inch, 16 gauge = .662 inch, 20 gauge = .615 inch, 28 gauge = .550 inch.

The 12 gauge shotgun is the most common shotgun gauge sold in America and is a good all-purpose gun — great for home defense, hunting, and skeet shooting. Because of their widespread use, ammo and accessories for 12 gauge shotguns are much easier to find than for other size shotguns. If you’re going to use your shotgun primarily for hunting or skeet shooting, you might follow the advice of shotgunning expert Bob Brister and go with a smaller gauge gun like a 20 or 28 gauge.

Chamber Length

In addition to a shotgun’s gauge number, another size you’ll see stamped on a shotgun’s barrel is the chamber length. The chamber is where the shell fits into the gun for firing. You need to make sure the length of the shell you’re loading into your gun matches the chamber length on your shotgun. Firing shells that are longer than the length of the chamber can generate dangerously high pressures in your gun. That’s a big safety risk.

Choke Tubes

As we mentioned earlier, when you fire a shotgun, the pellets in the shell spread as they leave the gun. When the pellets hit their target, they leave a spread pattern. Spread patterns can be small and dense or wide and sparse. The closer you are to your target, the more compact and lethal your spread pattern.

If you want to maintain a dense spread pattern when firing your shotgun at long distance targets (like you would when hunting), you’ll want to use a choke tube. A choke tube constricts a gun’s shot charge to hold it together longer before the shot spreads, thus giving a denser shot pattern at longer range than an open choke or no choke at all. Choke tubes come in a variety of sizes depending on how dense a pattern you want. If you’re simply using your shotgun for home defense, you probably don’t need a choke tube. They’re mainly used by hunters and skeet shooters.

Now that we’re familiar with the anatomy and workings of a shotgun, let’s get down to how to fire it. But first, please review the four cardinal rules of firing a gun.

Mike and the folks at the U.S. Shooting Academy teach their students to assume an athletic stance when firing a shotgun. Square your shoulders up with the target. Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart on a straight line. Stagger your strong-side foot about six inches behind your weak-side foot.

Place the buttstock of the shotgun near the centerline of the body and high up on the chest. Keep your elbows down.

Here’s Mike showing the athletic stance:

The biggest advantage of the athletic stance over the bladed stance (standing sideways) is that it helps in reducing the effects of recoil when firing a shotgun. Think about it. If you’re a lineman in football and you want to resist the other guy pushing you backwards, what stance would give you more balance? Being squared up with the other guy, or standing sideways with just one of your shoulders towards him? Squared up, of course.

Another advantage of the athletic stance is that it allows you to track a moving target better.

The act of putting a shotgun to your shoulder is called mounting the gun. But you don’t bring the gun to your shoulder straight off. You want to bring the side of the stock to your cheek first, before moving the buttstock to your shoulder.

Keeping your head up, bring the shotgun to your head. Press your cheek firmly to the side of the stock and then place the buttstock of the shotgun near the centerline of the body and high up on the chest, like so:

Trigger Hand Grip

On most shotguns you’ll find a crook between the stock and the trigger guard. Simply center the crook in the “V” junction of your thumb and index finger of your trigger hand. Grip the gun firmly, but not tightly.

If your shotgun has a pistol grip like Mike’s gun in the picture below, center the grip in the “V” at the junction of the thumb and index finger of your trigger hand. Grip the gun high on the backstrap (the backstrap is the back of the grip on the gun). Like so:

Support Hand Grip

The support hand should grip the fore-end of the shotgun roughly midway down the length of the shotgun. Here’s Mike demonstrating for us:

Putting your support hand further forward on the fore-end will give you finer control over the muzzle when aiming, which you want when precision is key. It will also give you more leverage against the gun which helps in recoil control.

You’ve probably seen movies where the action hero fires a shotgun in close quarters from the hip. I asked Mike about that.

“That’s a great technique…for the movies,” he said.

In other words, don’t use it in real life. It’s not safe and doesn’t provide any advantages other than looking cool.

If your target is really close to you, Mike suggests bringing the shotgun stock beneath your armpit in order to create more space between you and your target while maintaining more control. Here’s how it looks:

There’s a lot of debate among shotgunners about how you’re supposed to aim these things. You’ll hear many folks say, “You don’t aim a shotgun, you point it,” (See Shotgunning by Bob Brister.) Others will say you should aim it just like you would a rifle.

I asked Mike about this, and he said that while you should definitely aim a shotgun, the way you aim will be different depending on what sort of situation you’re in.

“You’re responsible for every shot you fire, so you better be sure you know where they’re going,” Mike advises. “Don’t just point it and start firing action movie style.”

Aiming a Shotgun in Home Defense and Large Game Hunting Situations

If you’re using a shotgun in a home defense situation or if you’re hunting deer with slugs, you’ll want to aim your shotgun just like you would when firing a rifle. Some shotguns have a rear sight notch and a bead at the end of the gun’s barrel (most shotguns don’t have a rear sight). Align those just as you would with a rifle. After you have proper sight alignment, you’ll want to set your sight picture. I talked about proper sight picture in our post about firing a handgun. The same principles apply here. I won’t repeat what I wrote, so refer back to that post for tips on aiming a shotgun.

Aiming a Shotgun in Small Game Hunting or Trap Situations

When you’re bird hunting or shooting skeet, you don’t have time for the deliberate aiming technique described above. If you try to aim like that, your bird will be long gone before you get a shot off. When you’re hunting small, fast-moving game or shooting clays with a shotgun, instead of carefully lining up your sights and putting all your focus on them like you would with a rifle, simply focus on the target, and fire.

“You also need to lead the target when firing at fowl. Don’t focus on the target itself, but rather the target’s front edge,” says Mike.

Unlike with a rifle or handgun where you slowly squeeze the trigger, with a shotgun you can use a more direct and less controlled trigger press. Again, when firing a shotgun, speed in getting off a shot is the goal.

The key to successful and safe gun training is practice. If you don’t own a shotgun, but are interested in purchasing one, find a local gun range and rent one for an hour. Ask to have someone show you how to fire it safely and correctly. Most places will be more than happy to help. If you already own a shotgun, here’s a friendly reminder to keep training.

Oh, and if you’re curious as to what sort of shotgun I ended up getting. It’s a Remington 870 Express.

Do you own a shotgun? Have any other tips for the first-time shotgun shooter? Share them with us in the comments!

Editor’s note: This article is about understanding the shotgun and how to fire one safely and correctly. It is not a debate about gun rights or whether guns are stupid or awesome. Keep it on topic or be deleted.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Special thanks goes out to Mike and the crew at U.S. Shooting Academy for their help on this article. Mike along with the U.S. Shooting Academy Handgun Manual were the sources for this article. If you’re ever in the Tulsa area, stop by their facility. It’s top notch and the staff and trainers are friendly, knowledgeable, and super badass.

The Updated Performance Center 686 and 686 Plus .357 Magnum revolvers feature enlarged sights and controls. (Photo: S&W)

Smith & Wesson is rolling out two updated Performance Center versions of their champion Model 686 revolvers for competition shooters. The new 686 and 686 Plus are full-size revolvers with enlarged sights and controls for flat-out fast shooting.

The Performance Center 686 is a standard six-shot revolver with a 4-inch barrel, while the Plus model has a seven-round cylinder and slightly longer 5-inch barrel. The 686 Plus also has a cylinder cut for moon clips for the fastest possible reloads.

The 4-inch Performance Center model. (Photo: S&W)

While these are both obviously designed for shooting sports, they’re good multi-purpose guns as well, suitable for self-defense and handgun hunting. Chambered for .357 Magnum, they’re both extremely versatile and can shoot a huge range of loads without issue.

The guns sport a satin stainless steel finish and chromed hammers and triggers for improved lubricity and durability. They also have solid, unfluted cylinders.

The combination doesn’t look bad, either. Complete with their full black synthetic grips and rear sights the guns have a bold two-tone appearance.

The upgraded guns have oversized, extended cylinder release levers and custom teardrop hammers. The triggers also come with overtravel stops to ensure short trigger pulls and clean breaks.

The new models feature thinned and vented, ribbed barrels with fully adjustable rear sights and big bright orange front sights.The front sight is interchangeable with different types or colors of sights.

The barrels also have tapered full-length underlugs. This type of underlug is designed to help control recoil without adding a lot of weight at the muzzle. This improves the gun’s balance and makes it fast and easy to get on target.

The 5-inch Performance Center Plus model. (Photo: S&W)

The 4-inch Performance Center 686 measures in at 9.5 inches long and weighs 38 ounces. The 686 Plus is an inch longer and half an ounce heavier.

At the heart of both guns is a tuned Performance Center trigger job. Every action is hand-fit for custom-level performance at production prices.

These Performance Center guns command a slight price premium — but not much. Both have a suggested price of $966, which is only a little more than $100 for all the upgrades. Street prices tend to be a little less than MSRP.

If you’ve been looking for a higher-end revolver that performs without breaking the bank maybe one of these is your next handgun.

| Ruger No. 1 | |

|---|---|

Ruger No. 1 rifle (with underlever down to open action)

|

|

| Type | Falling Block Rifle |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Bill Ruger |

| Designed | 1966 |

| Manufacturer | Sturm, Ruger & Co., Inc. |

| Unit cost | $1299[1] |

| Produced | 1967 – present[2] |

| Variants | Standard, Varmiter, Light Sporter, International, Tropical, Medium Sporter. |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 7 pounds (3.2 kg)[1] |

| Length | 36.5–42.5 inches (93–108 cm)[1] |

| Barrel length | 20–28 inches (51–71 cm)[1] |

|

|

|

| Cartridge | Various (see article) |

| Action | Farquharson-Style Hammerless falling block |

| Sights | none, or open sights |

The Ruger No. 1 is a single-shot rifle, with Farquharson-styleinternal hammer falling block action, manufactured by Sturm, Ruger. It was introduced in 1967.[3] An underlever lowers the block allowing loading and cocks the rifle. Lenard Brownell, commenting on his work at Ruger, said of the No. 1: “There was never any question about the strength of the action. I remember, in testing it, how much trouble I had trying to tear it up. In fact, I never did manage to blow one apart.”[4]

A shotgun-style tang safety works on the hammer and sear. Available with an Alexander-Henry, Beavertail, or Mannlicher style forearm in a multitude of calibers.

[hide]

Over the years, the No. 1 has been chambered in several different cartridges, among them .204 Ruger, .22 Hornet, .218 Bee, .222 Remington, .223 Remington, .22 PPC, .22-250 Remington, .220 Swift, 6mm PPC, 6 mm Remington, 6.5 Creedmoor, .243 Winchester, .257 Roberts, .25-06 Remington, .264 Winchester Magnum, .270 Winchester, .270 Weatherby Magnum, 6.5mm Remington, 6.5×55mm, 6.5×284 Norma, 7×57mm, 7mm-08, .280 Remington, 7 mm Remington Magnum, 7mm STW, 7.62x39mm, .308 Winchester, .30-30 Winchester, .30-40 Krag, .30-06 Springfield, .303 British, .300 Winchester Magnum, .300 H&H Magnum, .300 Weatherby Magnum, .338 Winchester Magnum, .357 Magnum, .375 H&H Magnum, .375 Ruger, .38-55 Winchester, .404 Jeffery, .405 Winchester, .416 Remington Magnum, .416 Ruger, .416 Rigby, .45-70 Government, .460 S&W Magnum, .458 Winchester Magnum, .458 Lott, 9.3×74mmR and .450/400 Nitro Express

The new Super Redhawk will show the world what 10mm can really do when you push it. (Photo: Ruger)

Ruger is expanding their Super Redhawk family of revolvers to include a new 6-shot model chambered for 10mm Auto. The company has been busy this season providing niche shooters with new revolvers chambered for a growing range of cartridges.

A revolver chambered for 10mm Auto is unusual for sure but the new Redhawk uses moon clips, making this gun fast to shoot and fast to reload.

Plus it provides 10mm shooters an avenue into revolvers if they don’t want to add a new cartridge to their collection.

Also, it’s just different. A 10mm Redhawk is capable of shooting .40 S&W in addition to 10mm, making it a versatile revolver whether it’s for plinking, hunting, or anything else.

Because it’s a Redhawk, shooters can count on the frame and lockup to handle the hottest and highest pressure loads.

Even with “Ruger-only” types of ammunition recoil isn’t going to be an issue with this gun. With its 6.5-inch barrel, it weighs over 3.3 pounds. That’s more than enough to bridle any 10mm load.

Especially since, by magnum revolver standards, 10mm is fairly entry level. Designed to push self-loading pistols to their limits, 10mm Auto is often loaded to just into .357 Magnum territories.

With this new Redhawk, Ruger is going to show off what 10mm Auto is really capable of.

The 10mm Redhawk has a suggested retail price of $1,159. Realistically that works out to street pricing in the $900 to $1,000 range.

The 10mm model has a brushed stainless finish with rubber and checkered wood grips.

It has a fully adjustable rear sight with a ramped red insert front sight. The frame is cut for an included set of scope rings for handgun hunters and each gun also comes with 3 full moon clips.

Both the grip and the sights are replaceable and the gun accepts a wide range of standard Super Redhawk accessories. Ruger typically sells additional moon clips in three packs for $15.

This is Ruger’s sixth new revolver of late. The company also recently launched a handful of new LCRx and SP101 revolvers in .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire, .327 Federal Magnum and 9mm Luger.

Ruger isn’t alone when it comes to fresh revolver announcements. Smith & Wesson just unveiled a pair of newPerformance Center 686 revolvers for competition and sport.

The world of revolvers is experiencing a kind of renaissance, with a lot of shooters turning to the classic wheel gun for fun, competition and self-defense. This 10mm revolver isn’t the first of its kind, and by the looks of it, probably won’t be the last.

I use to own one and was very surprised on how well it shot. But then I lent it out to a relative as they did not have any kind of gun in the house.

The Beretta 92 (also Beretta 96 and Beretta 98) is a series of semi-automatic pistols designed and manufactured by Beretta of Italy. The model 92 was designed in 1972 and production of many variants in different calibers continues today.

The United States Armed Forces replaced the M1911A1 .45 ACPpistol in 1985 with the M9, a military spec Beretta 92FS.

[hide]

The Beretta 92 pistol evolved from earlier Beretta designs, most notably the M1923 and M1951. From the M1923 comes the open slide design, while the alloy frame and locking block barrel, originally from Walther P38, were first used in the M1951. The grip angle and the front sight integrated with the slide were also common to earlier Beretta pistols. What were perhaps the Model 92’s two most important advanced design features had first appeared on its immediate predecessor, the 1974 .380 caliber Model 84. These improvements both involved the magazine, which featured direct feed; that is, there was no feed ramp between the magazine and the chamber (a Beretta innovation in pistols). In addition, the magazine was a “double-stacked” design, a feature originally introduced in 1935 on the Browning Hi-Power.[1]

Carlo Beretta, Giuseppe Mazzetti and Vittorio Valle, all experienced firearms designers, contributed to the final design in 1975.[2]

Production began in May 1976, and ended in February 1983. Approximately 7,000 units were of the first “step slide” design and 45,000 were of the second “straight slide” type.[3]

In order to meet requirements of some law enforcement agencies, Beretta modified the Beretta 92 by adding a slide-mounted combined safety and decocking lever, replacing the frame mounted manual thumb safety. This resulted in the 92S which was adopted by several Italian law enforcement and military units.

The 92SB, initially called 92S-1, was specifically designed for the USAF trials (which it won), the model name officially adopted was the 92SB. Features added include a firing pin block (thus the addition of the “B” to the name), ambidextrous safety levers, 3-dot sights, and relocated the magazine release catch from the bottom of the grip to the lower bottom of the trigger guard. The later relocation of the magazine release button means preceding models (92 & 92S) cannot necessarily use later magazines, unless they have notches in both areas.[4]

A compact version with a shortened barrel and slide and 13-round magazine capacity known as the 92SB Compact was manufactured from 1981 to 1991.[4]

Beretta modified the model 92SB slightly to create the 92SB-F (the “F” added to denote entry of the model in U.S. Government federal testing) by making the following changes:

The French military adopted a modified version of the 92F with a decocking-only lever as the PAMAS G1. These pistols have Tellurium in the slide, making the steel brittle and as such only have a service life of approximately 6,000 rounds. [1]

The FS has an enlarged hammer pin that fits into a groove on the underside of the slide. The main purpose is to stop the slide from flying off the frame to the rear if it cracks. This was in response to reported defective slides during U.S. Military testing.[6]

The Beretta 92’s open slide design ensures smooth feeding and ejection of ammunition and allows easy clearing of obstructions. The hard-chromed barrel bore reduces barrel wear and protects it from corrosion. The falling locking block design provides good accuracy and operability with suppressors due to the in-line travel of the barrel. This is in contrast to the complex travel of Browning designed barrels. The magazine release button is reversible with simple field tools. Reversing the magazine release makes left-handed operation much easier.

Increasingly, it has become popular to reduce handgun weight and cost as well as increase corrosion resistance by using polymers. Starting around the year 2000, Beretta began replacing some parts with polymer and polymer coated metal. Polymer parts include the recoil spring guide rod which is now also fluted, magazine floor plate, magazine follower and the mainspring cap/lanyard loop. Polymer coated metal parts include the left side safety lever, trigger, and magazine release button.[7]

To keep in line with the introduction of laws in some locations restricting magazines that hold more than 10 rounds, Beretta now manufactures magazines that hold fewer than the factory standard 15 rounds. These magazines have heavier crimping (deeper indentations in the side) to reduce the available space while still keeping the same external dimensions and ensuring that these magazines can be used on existing firearms. Beretta also produces 15 round “Sand Resistant” magazines to resolve issues encountered with contractor made magazines, and 17 round magazines included with the A1 models. Both magazines function in earlier 92 series and M9 model pistols.

Italian magazine manufacturer Mec-Gar now produces magazines in blue and nickel finishes with an 18-round capacity, which fit flush in the magazine well on the 92 series. Mec-Gar also produces an extended 20-round blued magazine that protrudes below the frame by 3⁄4 inch (19 mm). These magazines provide users in unrestricted states with a larger capacity magazine.

The Beretta 92 is available in many configurations and models:

The Beretta 93R is a significantly redesigned 92 to provide the option of firing in three-round bursts. It also has a longer ported barrel, heavier slide, fitting for a shoulder stock, a folding forward grip, and an extended magazine. Unlike other Berettas in the 90 series it is single-action only, does not have a decocker, and very few are around today.[5]:12–13

The Beretta 92 was designed for sports and law enforcement use and, due to its reliability, was accepted by military users in South America and other countries all over the world.