| Lee–Enfield |

|

| Type |

Bolt-action rifle |

| Place of origin |

United Kingdom |

| Service history |

| In service |

MLE: 1895–1926

SMLE: 1904–present |

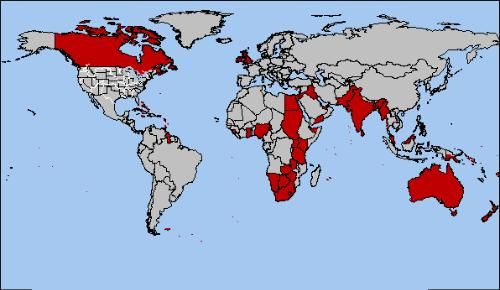

| Used by |

See Users |

| Wars |

Second Boer War

World War I

Easter Rising

Various Colonial conflicts

Irish War of Independence

Irish Civil War

World War II

Indonesian National Revolution

Indo-Pakistani Wars

Greek Civil War

Malayan Emergency

French Indochina War

Korean War

Arab-Israeli War

Suez Crisis

Border Campaign (Irish Republican Army)

Mau Mau Uprising

Vietnam War

The Troubles

Sino-Indian War

Bangladesh Liberation War

Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

Nepalese Civil War

Afghanistan conflict |

| Production history |

| Designer |

James Paris Lee, RSAF Enfield |

| Produced |

MLE: 1895–1904

SMLE: 1904–present |

| No. built |

17,000,000+ |

| Variants |

See Models/marks |

| Specifications |

| Weight |

4.19 kg (9.24 lb) (Mk I)

3.96 kg (8.73 lb) (Mk III)

4.11 kg (9.06 lb) (No. 4) |

| Length |

MLE: 49.6 in (1,260 mm)

SMLE No. 1 Mk III: 44.57 in (1,132 mm)

SMLE No. 4 Mk I: 44.45 in (1,129 mm)

LEC: 40.6 in (1,030 mm)

SMLE No. 5 Mk I: 39.5 in (1,003 mm) |

| Barrel length |

MLE: 30.2 in (767 mm)

SMLE No. 1 Mk III: 25.2 in (640 mm)

SMLE No. 4 Mk I: 25.2 in (640 mm)

LEC: 21.2 in (540 mm)

SMLE No. 5 Mk I: 18.8 in (480 mm) |

|

| Cartridge |

.303 Mk VII SAA Ball |

| Action |

Bolt-action |

| Rate of fire |

20–30 aimed shots per minute |

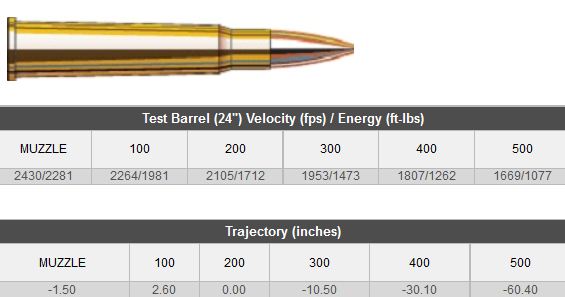

| Muzzle velocity |

744 m/s (2,441 ft/s) |

| Effective firing range |

550 yd (503 m)[2] |

| Maximum firing range |

3,000 yd (2,743 m)[2] |

| Feed system |

10-round magazine, loaded with 5-round charger clips |

| Sights |

Sliding ramp rear sights, fixed-post front sights, “dial” long-range volley; telescopic sights on sniper models. Fixed and adjustable aperture sights incorporated onto later variants. |

The Lee–Enfield is a bolt-action, magazine-fed, repeating rifle that was the main firearm used by the military forces of the British Empireand Commonwealth during the first half of the 20th century. It was the British Army‘s standard rifle from its official adoption in 1895 until 1957.. It is often referred to as the “SMLE,” which is short for “Short Magazine Lee-Enfield”.

A redesign of the Lee–Metford (adopted by the British Army in 1888), the Lee–Enfield superseded the earlier Martini–Henry, Martini–Enfield, and Lee–Metford rifles. It featured a ten-round box magazine which was loaded with the .303 Britishcartridge manually from the top, either one round at a time or by means of five-round chargers. The Lee–Enfield was the standard issue weapon to rifle companies of the British Army and other Commonwealth nations in both the Firstand Second World Wars (these Commonwealth nations included Australia, New Zealand, Canada, India and South Africa, among others). Although officially replaced in the UK with the L1A1 SLR in 1957, it remained in widespread British service until the early/mid-1960s and the 7.62 mm L42 sniper variant remained in service until the 1990s. As a standard-issue infantry rifle, it is still found in service in the armed forces of some Commonwealth nations, notably with the Bangladesh Police, which makes it the second longest-serving military bolt-action rifle still in official service, after the Mosin–Nagant. The Canadian Rangers reserve unit still use Enfield rifles, with plans to replace the weapons sometime in 2017–2018 with the new Sako-designed Colt C-19.[8] Total production of all Lee–Enfields is estimated at over 17 million rifles.

The Lee–Enfield takes its name from the designer of the rifle’s bolt system—James Paris Lee—and the factory in which it was designed—the Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield. In Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Southern Africa and India the rifle became known simply as the “three-oh-three“[9] or the “three-naught-three“.

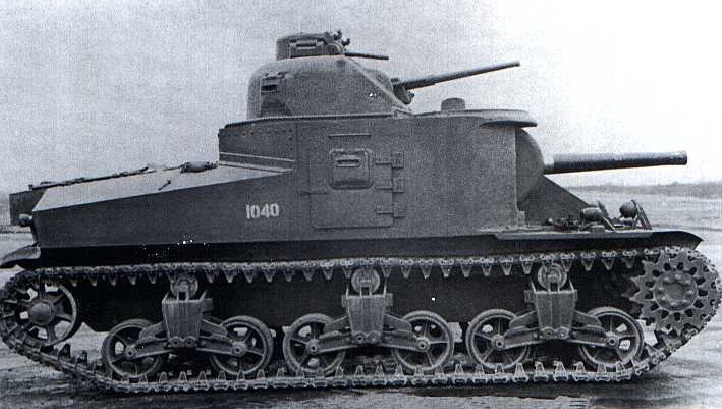

Design and history

The Lee–Enfield rifle was derived from the earlier Lee–Metford, a mechanically similar black-powder rifle, which combined James Paris Lee‘s rear-locking bolt system with a barrel featuring rifling designed by William Ellis Metford. The Lee action cocked the striker on the closing stroke of the bolt, making the initial opening much faster and easier compared to the “cock on opening” (i.e., the firing pin cocks upon opening the bolt) of the Mauser Gewehr 98 design. The rear-mounted lugs place the bolt operating handle much closer to the operator, over the trigger, making it quicker to operate than traditional designs like the Mauser. The action features helical locking surfaces (the technical term is interrupted threading). This means that final head space is not achieved until the bolt handle is turned down all the way. The British probably used helical locking lugs to allow for chambering imperfect or dirty ammunition and that the closing cam action is distributed over the entire mating faces of both bolt and receiver lugs. This is one reason the bolt closure feels smooth. The rifle was also equipped with a detachable sheet-steel, 10-round, double-column magazine, a very modern development in its day. Originally, the concept of a detachable magazine was opposed in some British Army circles, as some feared that the private soldier might be likely to lose the magazine during field campaigns. Early models of the Lee–Metford and Lee–Enfield even used a short length of chain to secure the magazine to the rifle.

The fast-operating Lee bolt-action and 10-round magazine capacity enabled a well-trained rifleman to perform the “mad minute” firing 20 to 30 aimed rounds in 60 seconds, making the Lee–Enfield the fastest military bolt-action rifle of the day. The current world record for aimed bolt-action fire was set in 1914 by a musketry instructor in the British Army—Sergeant Instructor Snoxall—who placed 38 rounds into a 12-inch-wide (300 mm) target at 300 yards (270 m) in one minute.[11]Some straight-pull bolt-action rifles were thought faster, but lacked the simplicity, reliability, and generous magazine capacity of the Lee–Enfield. Several First World War accounts tell of British troops repelling German attackers who subsequently reported that they had encountered machine guns, when in fact it was simply a group of well-trained riflemen armed with SMLE Mk III rifles.

The Lee–Enfield was adapted to fire the .303 British service cartridge, a rimmed, high-powered rifle round. Experiments with smokeless powder in the existing Lee–Metford cartridge seemed at first to be a simple upgrade, but the greater heat and pressure generated by the new smokeless powder wore away the shallow, rounded, Metford rifling after approximately 6000 rounds. Replacing this with a new square-shaped rifling system designed at the Royal Small Arms Factory (RSAF) Enfield solved the problem, and the Lee–Enfield was born.

Models/marks of Lee–Enfield Rifle and service periods

-

| Model/Mark |

In Service |

| Magazine Lee–Enfield |

1895–1926 |

| Charger Loading Lee–Enfield |

1906–1926 |

| Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk I |

1904–1926 |

| Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk II |

1906–1927 |

| Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk III/III* |

1907–present |

| Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk V |

1922–1924 (trials only; 20,000 produced) |

| Rifle No. 1 Mk VI |

1930–1933 (trials only; 1,025 produced) |

| Rifle No. 4 Mk I |

1931–present (2,500 trials examples produced in the 1930s, then mass production from mid-1941 onwards) |

| Rifle No. 4 Mk I* |

1942–present |

| Rifle No 5 Mk I “Jungle Carbine” |

1944–present (produced 1944–1947) BSA-Shirley produced 81,329 rifles and ROF Fazakerley 169,807 rifles. |

| Rifle No. 4 Mk 2 |

1949–present |

| Rifle 7.62mm 2A |

1964–present |

| Rifle 7.62mm 2A1 |

1965–present |

Magazine Lee–Enfield

The Lee–Enfield rifle was introduced in November 1895 as the .303 calibre, Rifle, Magazine, Lee–Enfield, or more commonly Magazine Lee–Enfield, or MLE (sometimes spoken as “emily” instead of M, L, E). The next year, a shorter version was introduced as the Lee–Enfield Cavalry Carbine Mk I, or LEC, with a 21.2-inch (540 mm) barrel as opposed to the 30.2-inch (770 mm) one in the “long” version. Both underwent a minor upgrade series in 1899 (the omission of the cleaning / clearing rod), becoming the Mk I*. Many LECs (and LMCs in smaller numbers) were converted to special patterns, namely the New Zealand Carbine and the Royal Irish Constabulary Carbine, or NZ and RIC carbines, respectively. Some of the MLEs (and MLMs) were converted to load from chargers, and designated Charger Loading Lee–Enfields, or CLLEs.

Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk I

A shorter and lighter version of the original MLE—the famous Rifle, Short, Magazine, Lee–Enfield, or SMLE (sometimes spoken as “Smelly”, rather than S, M, L, E)—was introduced on 1 January 1904. The barrel was now halfway in length between the original long rifle and the carbine, at 25.2 inches (640 mm).

The SMLE’s visual trademark was its blunt nose, with only the bayonet boss protruding a small fraction of an inch beyond the nosecap, being modeled on the Swedish Model 1894 Cavalry Carbine. The new rifle also incorporated a charger loading system,[18] another innovation borrowed from the Mauser rifle’ and is notably different from the fixed “bridge” that later became the standard, being a charger clip (stripper clip) guide on the face of the bolt head. The shorter length was controversial at the time: many Rifle Association members and gunsmiths were concerned that the shorter barrel would not be as accurate as the longer MLE barrels, that the recoil would be much greater, and the sighting radius would be too short.

Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk III

Short Magazine Lee–Enfield No. 1 Mk. III

Magazine Cut-Off on an SMLE Mk III rifle—this feature was removed on the Mk III* rifle.

The iconic Lee–Enfield rifle, the SMLE Mk III, was introduced on 26 January 1907, along with a Pattern 1907 (P’07) sword bayonet and featured a simplified rear sight arrangement and a fixed, rather than a bolt-head-mounted sliding, charger guide. The design of the handguards and the magazine were also improved, and the chamber was adapted to fire the new Mk VII High Velocity spitzer .303 ammunition. Many early model rifles, of Magazine Lee–Enfield (MLE), Magazine Lee–Metford (MLM), and SMLE type, were upgraded to the Mk III standard. These are designated Mk IV Cond., with various asterisks denoting subtypes.

During the First World War, the SMLE Mk III was found to be too complicated to manufacture (an SMLE Mk III rifle cost the British Government £3/15/-) and demand was outstripping supply, so in late 1915 the Mk III* was introduced, which incorporated several changes, the most prominent of which were the deletion of the magazine cut-off mechanism, which when engaged permits the feeding and extraction of single cartridges only while keeping the cartridges in the magazine in reserve, and the long-range volley sights. The windage adjustment of the rear sight was also dispensed with, and the cocking piece was changed from a round knob to a serrated slab. Rifles with some or all of these features present are found, as the changes were implemented at different times in different factories and as stocks of existing parts were used. The magazine cut-off was reinstated after the First World War ended and not entirely dispensed with until 1942.

The inability of the principal manufacturers (RSAF Enfield, The Birmingham Small Arms Company Limited and London Small Arms Co. Ltd) to meet military production demands, led to the development of the “peddled scheme”, which contracted out the production of whole rifles and rifle components to several shell companies.

The SMLE Mk III* (renamed Rifle No.1 Mk III* in 1926) saw extensive service throughout the Second World War as well, especially in the North African, Italian, Pacific and Burmese theatres in the hands of British and Commonwealth forces. Australia and India retained and manufactured the SMLE Mk III* as their standard-issue rifle during the conflict and the rifle remained in Australian military service through the Korean War, until it was replaced by the L1A1 SLR in the late 1950s. The Lithgow Small Arms Factory finally ceased production of the SMLE Mk III* in 1953.

The Rifle Factory at Ishapore, West Bengal, India produced the MkIII* in .303 British and then upgraded the manufactured strength by heat treatment of the receiver and bolt to fire 7.62×51mm NATO ammunition, the model 2A, which retained the 2000 yard rear sight as the metric conversion of distance was very close to the flatter trajectory of the new ammunition nature, then changed the rear sight to 800m with a re-designation to model 2A1. Manufactured until at least the 1980s and continues to produce a sporting rifle based on the MkIII* action.

Pattern 1913 Enfield

Due to the poor performance of the .303 British cartridge during the Second Boer War from 1899–1902, the British attempted to replace the round and the Lee–Enfield rifle that fired it. The main deficiency of the rounds at the time was that they used heavy, round-nosed bullets that had low muzzle velocities and poor ballistic performance. The 7mm Mauserrounds fired from the Mauser Model 1895 rifle had a higher velocity, flatter trajectory and longer range, making them superior on the open country of the South African plains. Work on a long-range replacement cartridge began in 1910 and resulted in the .276 Enfield in 1912. A new rifle based on the Mauser design was created to fire the round, called the Pattern 1913 Enfield. Although the .276 Enfield had better ballistics, troop trials in 1913 revealed problems including excessive recoil, muzzle flash, barrel wear and overheating. Attempts were made to find a cooler-burning propellant but further trials were halted in 1914 by the onset of World War I. This proved fortunate for the Lee–Enfield, as wartime demand and the improved Mk VII loading of the .303 round, caused it to be retained for service.[27]

Pattern 1914/US M1917

The Pattern 1914 Enfield and M1917 Enfield rifles are based on the Enfield-designed P1913, itself a Mauser 98 derivative and not based on the Lee action, and are not part of the Lee–Enfield family of rifles, although they are frequently assumed to be.

Inter-war period

Lee–Enfield No. 4 Mk I Longbranch aperture sights

In 1926, the British Army changed their nomenclature; the SMLE became known as the Rifle No. 1 Mk III or III*, with the original MLE and LEC becoming obsolete along with the earlier SMLE models. Many Mk III and III* rifles were converted to .22 rimfire calibre training rifles, and designated Rifle No. 2, of varying marks. (The Pattern 1914 became the Rifle No. 3.)

The SMLE design was a relatively expensive long arm to manufacture, because of the many forging and machiningoperations required. In the 1920s, a series of experiments resulting in design changes were carried out to help with these problems, reducing the number of complex parts and refining manufacturing processes. The SMLE Mk V (later Rifle No. 1 Mk V), adopted a new receiver-mounted aperture sighting system, which moved the rear sight from its former position on the barrel. The increased gap resulted in an improved sighting radius, improving sighting accuracy and the aperture improved speed of sighting over various distances. In the stowed position, a fixed distance aperture battle sight calibrated for 300 yd (274 m) protruded saving further precious seconds when laying the sight to a target. An alternative developed during this period was to be used on the No. 4 variant, a “battle sight” was developed that allowed for two set distances of 300 yards and 600 yards to be quickly deployed and was cheaper to produce than the “ladder sight”. The magazine cutoff was also reintroduced and an additional band was added near the muzzle for additional strength during bayonet use. The design was found to be even more complicated and expensive to manufacture than the Mk III and was not developed or issued, beyond a trial production of about 20,000 rifles between 1922 and 1924 at RSAF Enfield. The No. 1 Mk VI also introduced a heavier “floating barrel” that was independent of the forearm, allowing the barrel to expand and contract without contacting the forearm and interfering with the ‘zero’, the correlation between the alignment of the barrel and the sights. The floating barrel increased the accuracy of the rifle by allowing it to vibrate freely and consistently, whereas wooden forends in contact with barrels, if not properly fitted, affected the harmonic vibrations of the barrel. The receiver-mounted rear sights and magazine cutoff were also present and 1,025 units were produced between 1930 and 1933.

Lee–Enfield No. 1 Mk V

Long before the No. 4 Mk I, Britain had obviously settled on the rear aperture sight prior to WWI, with modifications to the SMLE being tested as early as 1911, as well as later on the No. 1 Mk III pattern rifle. These unusual rifles have something of a mysterious service history, but represent a missing link in SMLE development. The primary distinguishing feature of the No. 1 Mk V is the rear aperture sight. Like the No. 1 Mk III* it lacked a volley sight and had the wire loop in place of the sling swivel at the front of magazine well along with the simplified cocking piece. The Mk V did retain a magazine cut-off, but without a spotting hole, the piling swivel was kept attached to a forward barrel band, which was wrapped over and attached to the rear of the nose cap to reinforce the rifle for use with the standard Pattern 1907 bayonet. Other distinctive features include a nose cap screw was slotted for the width of a coin for easy removal, a safety lever on the left side of the receiver was slightly modified with a unique angular groove pattern, and the two-piece hand guard being extended from the nose cap to the receiver, omitting the barrel mounted leaf sight. No. 1 Mk V rifles were manufactured solely by R.S.A.F. Enfield from 1922–1924, with a total production of roughly 20,000 rifles, all of which marked with a “V”.

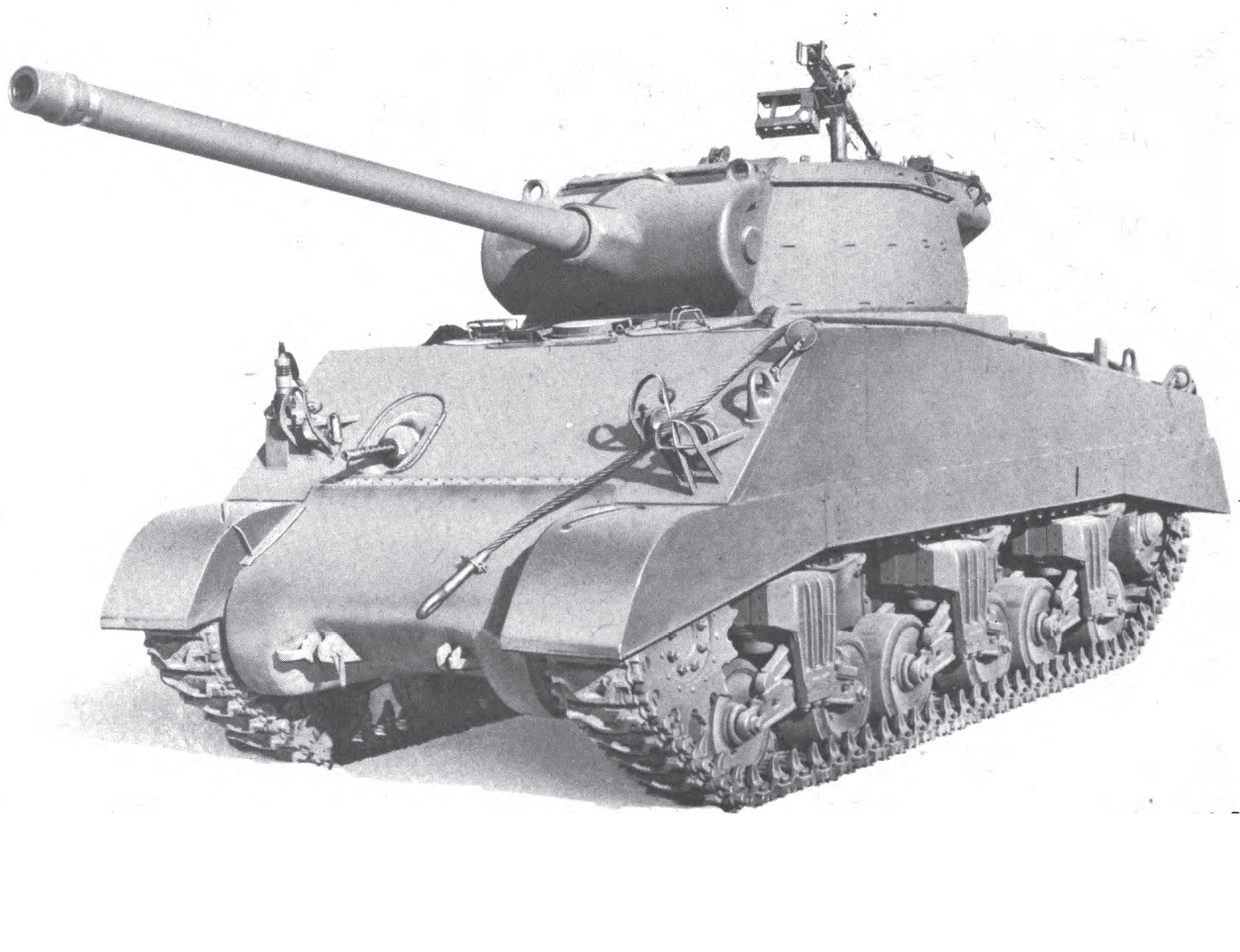

Rifle No. 4

Lee–Enfield No. 4 Mk I

Lee–Enfield No. 4 Mk 2 with the ladder aperture sight flipped up and 5-round

charger

By the late 1930s, the need for new rifles grew and the Rifle, No. 4 Mk I was officially adopted in 1941. The No. 4 action was similar to the Mk VI, but stronger and most importantly, easier to mass-produce. Unlike the SMLE, that had a nose cap, the No 4 Lee–Enfield barrel protruded from the end of the forestock. The charger bridge was no longer rounded for easier machining. The iron sightline was redesigned and featured a rear receiver aperture battle sight calibrated for 300 yd (274 m) with an additional ladder aperture sight that could be flipped up and was calibrated for 200–1,300 yd (183–1,189 m) in 100 yd (91 m) increments. This sight line like other aperture sight lines proved to be faster and more accurate than the typical mid-barrel rear sight elements sight lines offered by Mauser, previous Lee–Enfields or the Buffington battle sight of the 1903 Springfield.

The No. 4 rifle was heavier than the No. 1 Mk. III, largely due to its heavier barrel and a new bayonet was designed to go with the rifle: a spike bayonet, which was essentially a steel rod with a sharp point and was nicknamed “pigsticker” by soldiers. Towards the end of the Second World War, a bladed bayonet was developed, originally intended for use with the Sten gun—but sharing the same mount as the No. 4’s spike bayonet—and subsequently the No. 7 and No. 9 blade bayonets were issued for use with the No. 4 rifle as well.However, in McAuslan in the Rough, George MacDonald Fraser alleges that the Pattern 1907 bladed bayonet used with the SMLE was also compatible with the No. 4 rifle.[35]

During the course of the Second World War, the No. 4 rifle was further simplified for mass-production with the creation of the No. 4 Mk I* in 1942, with the bolt release catch replaced by a simpler notch on the bolt track of the rifle’s receiver. It was produced only in North America, by Long Branch Arsenal in Canada and Savage-Stevens Firearms in the USA.The No.4 Mk I rifle was primarily produced for the United Kingdom.

In the years after the Second World War, the British produced the No. 4 Mk 2 (