The Smith & Wesson .44 Magnum has a distinctly American backstory. Introduced to much fanfare in 1955 as the “most powerful handgun in the world,” the .44 arrived at a time when we were adding muscle and power to cars, jets and space rockets. The .44 Mag. was a dramatic leap ahead of the previous record holder, the .357 Mag., in a similarly sized, large-frame Smith & Wesson double-action revolver. The revolver now known as the Model 29 was introduced simply as “the .44 Magnum,” and it was a premium product in every respect. This deluxe status followed the precedent of the “Registered Magnums” that accompanied the release of the .357 Mag. cartridge. The .44 Magnum was a real achievement; shooters now had a sidearm that could deliver more energy than many of the popular rifles of the frontier era.

The new Smith .44 was an immediate success and became an iconic symbol for Smith & Wesson. Even now, the wrapper in which Smith & Wesson handguns are shipped are printed with the familiar profile of the original .44 Magnum. Collectors and shooters alike are deeply passionate about the early “Pre-Model 29” .44 Magnum N-frames. There is something undeniably special about them, and the prices reflect this, with the early revolvers selling for double or triple of what a later sample brings. Smith & Wesson made a relatively small number of the early revolvers before deleting the upper sideplate screw, making the .44 a “four screw” rather than the original five. A short time later, in 1957, the factory adopted model numbers, with the .44 Magnum becoming the Model 29.

Legendary gun writer Elmer Keith lobbied aggressively for what became the .44 Mag. cartridge for many years, and he had this to say in the 1966 printing of his definitive book Sixguns: “The [Magnum] was a masterpiece, both as to accuracy and careful fitting and sighting. In fact, I consider it the finest product of the Smith & Wesson factory.”

Keith quoted a S&W manager who described the new magnum as coming off the assembly line only as fine, hand-fitted, super-grade guns. It is worth keeping in mind that this was at a time that many view as the “golden age” of S&W, so super grade at that time must have really been special.

I was recently able to extensively handle and fire a pristine, five-screw .44 Magnum. This Smith was one of only several hundred 4″ models produced in those first years, the bulk of the first thousands produced sporting the heavy, ribbed 6½” barrel. This particular revolver was later returned to the factory for a nickel refinish and appeared to be unfired following that refinish when I first inspected it. Nickel can look a little flashy on many firearms, but, in my book, a nickel 4″ N-frame is one of the most handsome handguns ever made. This sample had a level of polish, fitting and workmanship that was super grade in every sense of the term.

I was recently able to extensively handle and fire a pristine, five-screw .44 Magnum. This Smith was one of only several hundred 4″ models produced in those first years, the bulk of the first thousands produced sporting the heavy, ribbed 6½” barrel. This particular revolver was later returned to the factory for a nickel refinish and appeared to be unfired following that refinish when I first inspected it. Nickel can look a little flashy on many firearms, but, in my book, a nickel 4″ N-frame is one of the most handsome handguns ever made. This sample had a level of polish, fitting and workmanship that was super grade in every sense of the term.

There are a variety of features that distinguish a “Pre-29” or “Five-Screw” Smith from those that would follow in later years. Arguably no single one of these matters, but as a group, they add to the overall richness of the whole. There are the countersunk, recessed-rim chambers that fully enclose the case heads. The repetition of the serial number on the rear of the cylinder and the inside of the ejector-rod shroud adds a touch of class. These parts didn’t just end up together; they were meant to be mated. The screws at the top of the sideplate and the forward curvature of the trigger guard speak to the old manner of assembly—not necessarily better but different, and, with the passage of time, distinguished.

In discussing the Smiths of this era, a highly respected pistolsmith remarked that, by today’s standards of custom, each revolver—particularly the high-end models like the .44 Magnum—were truly hand-built and fitted with “honed lockwork parts,” according to the early advertisements. This level of fitting is the magic that makes the Golden Era guns so special. However, hand-fitting/honing inevitably yields a level of variability from revolver to revolver. They will certainly all meet the expected standards, but the feel of how the parts interact can be distinct from one N-frame to the next. There is a uniqueness to the timing and trigger pulls on the big Smiths that seem to be the personality of the big-belt guns. This particular Pre-29 has a precision to the timing that is an enduring testament to the mastery of the craftsman who fitted it. Cocking this .44 Magnum is an experiential sonnet of American exceptionalism in the post-war era.

Rolling through the double-action pull is a real treat. It is almost perfectly smooth and even, the heavy-profile short barrel holding the front sight relatively still in the notch as the big hammer retracts and falls. Weight of the pull measures 10 lbs. but feels lighter. I often marvel at how a big Smith can rotate and lock a rather large cylinder and simultaneously cycle that target hammer while the shooter simply feels a smooth, even pull. There may be a lot of physical work being done, but the beauty of leverage and careful polishing hides it all from the shooter. There are more than a few double-action semi-automatics where the shooter feels like he or she is doing a lot of work and feeling a bunch of parts rub together to simply retract and drop a little hammer.

Rolling double-action shots onto somewhat challenging targets is one of my favorite shooting pastimes. I have the great fortune of being able to shoot a wide variety of firearms and in different settings. Shooting this S&W with low-pressure .44 Spl. loads is just plain fun. I tried Black Hills’ 210-grain lead flat points, as well as Magtech 240-grain jacketed flat points, and both are pushing mass and velocity that were considered serious manstoppers in days of yore. The feel through the N-frame magnum, though, is surprisingly mild. Casually connecting on my 3″x6″ steel “truth teller” target in double action from about 25 yards was pure joy.

Rolling double-action shots onto somewhat challenging targets is one of my favorite shooting pastimes. I have the great fortune of being able to shoot a wide variety of firearms and in different settings. Shooting this S&W with low-pressure .44 Spl. loads is just plain fun. I tried Black Hills’ 210-grain lead flat points, as well as Magtech 240-grain jacketed flat points, and both are pushing mass and velocity that were considered serious manstoppers in days of yore. The feel through the N-frame magnum, though, is surprisingly mild. Casually connecting on my 3″x6″ steel “truth teller” target in double action from about 25 yards was pure joy.

One could shoot nothing but Specials in the .44 S&W and be perfectly happy. However, the whole point of the model was the introduction of the .44 Mag. cartridge, and the Smith takes on an entirely different character when the magnums are nestled into those recessed chambers. You simply don’t get to push 800 ft.-lbs. of energy out of a 42-oz. revolver without noticing it. The carry-friendly 4″ barrel ensures that the ignition is regularly accompanied by a fearsome daylight fireball, and the velocity makes a violent racket. I can imagine that the experience was jarring to the 1950s shooting public baselined on firing mild .38 Spls., with either no or ineffectual hearing protection. Many of those shooters undoubtedly formed the “For sale: used, like-new, fired only six shots” story that has been so often repeated.

The stocks on those early guns are a story of their own. Known widely as “Cokes,” the striking gonçalo alves wood was a departure from traditional walnut, and they were shaped with a mild curvature and swell that resembles an old-fashioned bottle of Coca Cola. The shaping and fitting on the stocks is, well, magnificent. They feel great in the hand, work well in both single- and double-action modes and handle recoil reasonably well. Smith & Wesson kept the basic profile of the stocks, but, over time, the later renditions became increasingly large, square and blocky—until they almost single-handedly boosted the aftermarket replacement makers such as Pachmayr. One indication of just how good the old Coke stocks were can be found in the current price of a set being sold separately from its magnum. Shooter-grade sets that show their age often go for more than a new J-frame revolver. Pristine sets can go for as much or more than a complete shooter-grade Model 29 from the later decades.

Recoil in the S&W was at the level where an experienced shooter can manage it in moderate doses. A somewhat-seasoned shooter can tolerate it for a few occasional shots in the field or the range, and a novice may either enjoy the experience or be mildly scarred, depending on their outlook. There is no doubt that serious energy is being unleashed, and the experience was intense with full-power loads.

Lighter .44 Mag. revolvers are now relatively commonplace, but the original may still be one of the best compromises—light enough to carry but heavy enough to shoot and control the significant energy being launched. Magnums that are more pleasant to shoot tend to be inconveniently heavy and unlikely to be carried far or often. Really light .44 Mag. revolvers are at their best with moderate .44 Mag. loads, with many shooters finding them downright unpleasant or even painful with stout ammunition.

I find one of the most significant shooting challenges out there is shooting groups with a heavy-recoiling magnum. For me, it is a test of willpower and discipline like few others—not quite as hard as walking by a plate of cookies fresh from the oven without taking one, but still very hard. I spent the bulk of my adult life in the Marine Corps, where discipline is valued like gold bullion, and I find nestling behind a carry-weight magnum and trying to shoot to its potential to be at once intimidating and a worthy challenge. The Pre-29s have a reputation for accuracy, but you have to not flinch as the gun bucks and roars to prove it.

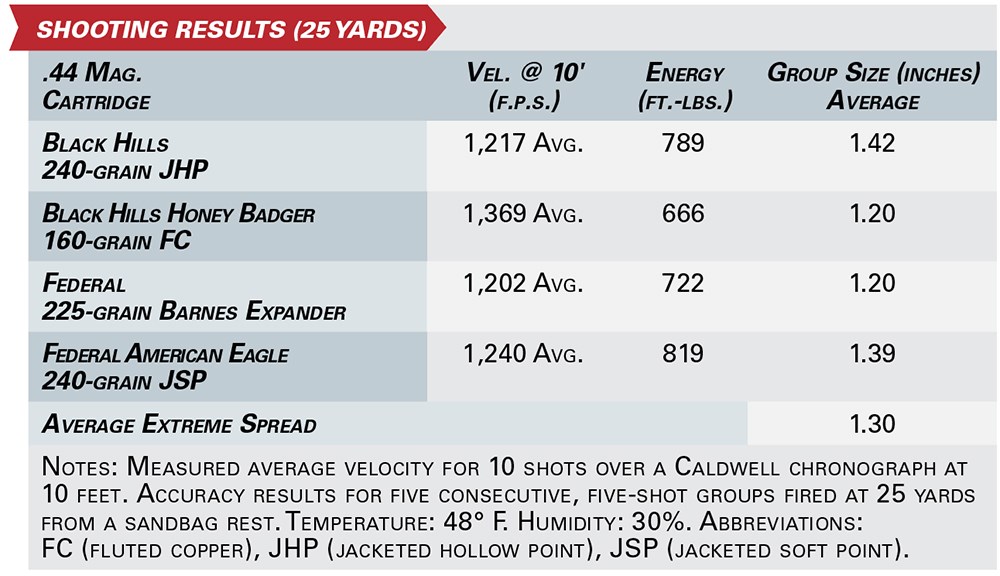

The 1956 gun shot every bit as well as its legendary status would suggest. Federal 220-grain solid-copper hollow points printed a 1.2″ 25-yard group, and American Eagle 240-grain soft points fared just under 0.2″ larger. Black Hills’ 240-grain JHPs roared into 1.42″ and the company’s 160-grain fluted Honey Badgers cut their distinctive holes into 1.2″ clusters.

When I saw how well the .44 Magnum shot, I was happy and a little relieved. I then started thinking how to put some practical challenges to the S&W. Not quite Elmer Keith’s famous shots dispatching a wounded mule deer escaping at 600 yards with his magnum, but what might I be able to do with this particular one? I had been working on a rifle at 100 yards, and had, on a whim, fired four of the Federal 220s over a barricade at a bullseye, grouping just off the paper in a spread I could cover with my hand. The Black Hills 240s hit very nearly dead-on at 100 yards with no sight change, so I set up a Defense Targets 9.5″x20″ reduced steel silhouette and set forth to make it ring.

I rested the revolver on a beanbag rest flopped over a sawhorse and knelt down solidly behind it getting my natural point of aim set and thinking positive thoughts. I gently added pressure to the curved target trigger, a special, deluxe feature that was introduced as standard on the .44 Magnum, and the blast of the shot melded into the deep bass tone of the steel being rung hard at center. The next three shots felt equally good, and I could almost make out the splatter on the target forming a group right under where I was holding the front sight. On the fifth shot I didn’t give the trigger press 100 percent of the respect it deserved and called the shot a touch left. At 100 yards, “a touch left” pushed the impact more than 5″ from the center to the edge of target; it served as a reminder of the level of concentration required.

I redoubled my efforts and knew, as the S&W rocked upward, that the shot was good. The 100 yards down to the target was one of those walks where you think something special just happened and are eager for the paces to bring you into visual confirmation that the group you think you saw is what is actually there. The super-grade magnum had hammered those .44-cal. JHPs into a 4.6″ group on the steel.

There have been tens of thousands of S&W .44 Mag. revolvers made since that dramatic launch some 65 years ago. There have been both larger and smaller magnum revolvers from numerous makers and a half dozen or more cartridges that eclipse the power of the .44. Nonetheless, to this day, the .44 Mag. retains a mystique, and its original Smith & Wesson N-frame platform an aura that extends beyond the shooting world and into the popular culture. Any shooter lucky enough to examine one of the early Pre-29s is likely to string a bunch of very complimentary adjectives together. After some long deliberation, I chose just one that I think suits its power, old-world quality and grace … and that is majestic.