Before sending these NCOs their orders, the Army did not verify with them if it made sense for their families, their career ambitions, or their current units of assignment. The bureaucrats who decided to upend these NCOs’ lives did not know if the NCOs were ideal candidates to be recruiters. Instead, they provided hundreds of NCOs a new reason to be cynical about the Army’s personnel policies and sent them into American society to sell the Army.

The Army’s impersonal, centralized personnel system not only hindered recruiting efforts, it also likely led to many of these NCOs considering leaving the Army. This story is an example of the Army asking the wrong question in its recruiting crisis. Instead of asking how it can increase recruiting, the Army should be asking how it can retain soldiers so that it does not need to churn through so many recruits.

To solve its manning problem, the Army must return to a long-term service model that values people over the efficiency of a centralized personnel system. Before the 1940s, the Army had a long-term service model, but with the transition to a mass Army of short-term draftees, it shifted to a centralized personnel systems based on scientific management. This centralized system relied on rigid career paths, competitive evaluations, and an up-or-out system of promotions. It prioritized efficient, centralized allocation of personnel at the cost of dehumanizing soldiers by treating them as interchangeable cogs to drive the green machine. In adopting these policies, the Army transitioned from a pre–World War II personnel system based on professionalism and long-term service to one of careerism and churn. To return to long-term service, the Army must promote retention by providing increased purpose, stability, and career satisfaction through decentralized, flexible personnel policies.

The 1940s Roots of the 2020s Recruiting Crisis

In the 1940s, the Army established a personnel system that assumed a steady stream of short-term soldiers. It was initially supported by conscription, and after the adoption of the all-volunteer force (AVF) in 1973, it was enabled by wage stagnation and a lack of economic opportunities particularly for Black Americans and southerners. These societal enablers of a short-term service model no longer exist, and long-term economic and society trends mean the recruiting environment is unlikely to improve.

The Army has been ramping up recruiting efforts after it missed its fiscal year 2022 recruiting goal by 25 percent, and yet in 2023, it still fell 10 percent short of its annual target of sixty-five thousand recruits. The Army has been trying to solve this problem through solutions such as a new three-star command, career fairs, and new “talent acquisition” jobs. Though even with these solutions in place, the Army expects to eventually reach just sixty thousand recruits.

Additional recruiting efforts already face diminishing returns. Already in 2018, the Army increased the number of recruiters and revamped its marketing to meet a shortfall of just 6,500 soldiers, but the problem only worsened. Back in 2015, Undersecretary of the Army Brad R. Carson recognized that increasing recruiting efforts could not maintain an unsustainable personnel system: “It is my firm belief that the current personnel system, which has satisfactorily served us well for 75 years now, has become outdated,” Carson said. “What once worked for us has now, in the 21st century, become unnecessarily inflexible, inefficient, and irreparable.”

The AVF was adopted in 1973 after its recommendation by the Gates Commission, which expected the Army to transition to a longer-term service model with turnover reducing from 26 percent a year to 17 percent a year. With the increased retention of such a model, the voluntary army would require fewer recruits, which would ensure its sustainability. The commission estimated that the military required 265,000 recruits each year to support a force level of 2.1 million. But instead, even with pay increases between 50 and 100 percent, turnover did not decrease, and the military found itself having to enlist up to 470,000 recruits each year. The Army struggled to meet these goals.

In 1977, a RAND report questioned the long-term sustainability of the AVF if the military did not reduce turnover. It found that the military’s personnel policies developed over the draft era focused on allowing ease of management rather than meeting the country’s requirements. The military wanted predictable career patterns for centralized management. It became so habituated to these processes that it kept them after the end of the draft. Voluntary service did not increase retention because the Army maintained its 1940s personnel policies.

Economic Progress Means the Recruiting Crisis will Persist

Since the inception of the AVF, there have been worries that economic growth would hamper recruitment, but fortuitous recessions and wage stagnation saved the AVF. As William King reported on the first year of the AVF, “The Army fell more than 23,000 soldiers short of its recruiting objectives.” He attributed improved performance in the AVF’s second year partly to adjustments in recruiting practices—but also, crucially, to an economic recession.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the Army could attract working-class recruits due to working-class wages stagnating while military pay increased. An article on the twentieth anniversary of the AVF highlighted how recruiting benefited from deindustrialization: “Instead of competing against the lure of relatively high paying factory jobs, military recruiters could offer an alternative to low paying, dead-end jobs in the service industries. In fact, real wages of high school graduates fell through the decade of the 1980s.” However, in the last few years, working-class wages have increased and provided well-paying alternatives to enlistment.

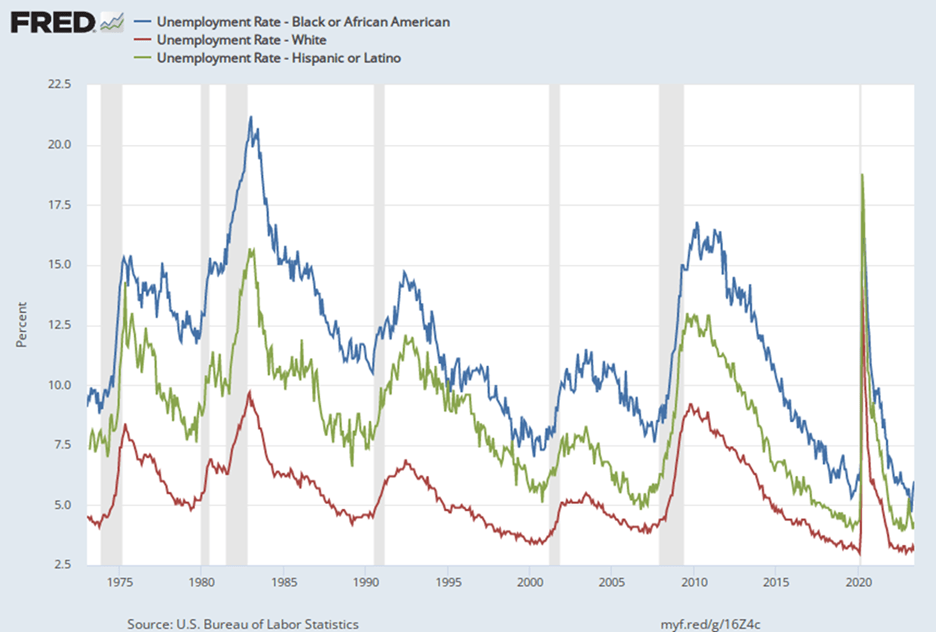

In addition to wage stagnation, the AVF initially benefited from the lack of opportunity for Black Americans. In 1977, they were 11 percent of the American population but 23.7 percent of the Army. They enlisted and reenlisted at much higher rates than White Americans. Now the Army can no longer rely on Black Americans lacking alternative opportunities. Their unemployment rate reached a record low of 4.7 percent in 2023.

Furthermore, since the 1800s, the Army has relied on the relatively impoverished South, which lagged in industrialization, to provide a disproportionate share of recruits. The South has been catching up to the rest of the country. In the 1980s, the Midwest had 25 percent more workers in industry than in the South. Now the regions are level on their percentage of workers in industry. With more economic opportunities in the South for the working class, the Army will find it a less lucrative source of recruits.

The Post-9/11 Wars delayed the Recruiting Crisis

In the early 2000s, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq mitigated the effects of societal changes on recruiting. Throughout much of American history, the public has rallied to the colors during wartime. But in peacetime, Americans have not viewed the Army as a high-prestige occupation. In 2021, after the withdrawal from Afghanistan brought the era of the post-9/11 wars to its denouement, only 9 percent of the American population between the ages of sixteen and twenty-one said they would consider military service, which was down from 13 percent in 2018 and a lower rate than any point during the post-9/11 era.

Without a war to fight, it can be hard to find purpose in military service. While some commentators turn to simplistic generational stereotypes to explain the current generation’s lack of interest in the military, it should be seen as return to a disinterested norm. As Morris Janowitz explained, in peacetime American society, “Entry into the military is often thought of as an effort to avoid the competitive realities of civil society. In the extreme view, the military profession is thought to be a berth for mediocrity.” Even in 1955, in a country full of veterans of World War II, the public ranked enlisted service as a low-prestige career. It placed fourteenth of sixteen working class occupations listed on a survey. Such surveys show that a lack of interest in service does not come from a lack of awareness. Those veterans of World War II might have thought military service was noble during wartime but did not want their children to deal with the Army’s personnel system during peacetime. Today, the same trend is occurring. The Army’s own survey in 2021 found that just 53 percent of active soldiers would recommend service to someone they cared about.

While in the past Army service may not have been attractive, before World War II, the Army could rely on those who joined to commit to long-term service. An illustrative data point is the collapse in retention of officers commissioned through West Point. Before World War I, only 12.5 percent of West Point officers had resigned their commissions before retirement. By World War II, a slight increase to 14.9 percent had resigned before retirement. By the 1950s, after the Army changed to scientific management personnel policies, between 20 and 25 percent of each class resigned after just five years of service. That relative trickle turned into a flood over the following decades. 62 percent of the class of 2004 resigned within ten years after commissioning. Not only West Point retention collapsed after the 1940s. In 1955, President Dwight Eisenhower wrote a letter to Congress concerned with the fall in Army officer and enlisted retention, in which he cites that only 11.6 percent of personnel reenlisted in 1954 compared to 41.2 percent in 1949.

A Divisional System Will Increase Commitment to Long-Term Service

To transition to a long-term service model, the Army must move away from the personnel system codified in the 1940s that turned people into interchangeable cogs. The first step to increase commitment for a long-term service model would be to transition to a divisional system of assignment similar to the regimental system used by Commonwealth armies today.

While the US Army used a decentralized regimental system in the nineteenth century, the Army weakened it between the Spanish-American War and World War II. To rapidly create a mass Army, the service followed the path of many twentieth-century bureaucracies. James C. Scott explained in Seeing Like a State that modern bureaucracies sought to rationalize society through centralized, scientific management approaches. In their drive for efficiency, these approaches dehumanized populations, created inflexibility, and were often brutally ineffective.

During World War II, in a change from previous wars, American replacements traveled to combat theaters as individuals to efficiently replenish units. As they deployed, unsure of what unit they would join, soldiers complained they of being “herded like sheep” or “handled like so many sticks of wood.” After weeks of travel, they “wanted most of all to be identified with a unit.” Medical officers blamed the replacement system for psychological damage that led to high rates of psychiatric casualties before soldiers even reached the front. For a time, the Army discharged more men for psychiatric reasons then it received as replacements, leading General George Marshall to set up an investigation into the psychiatric crisis. Observing the crisis, Brigadier General Thomas Christian, commander of the Field Artillery School at Camp Roberts, recommended to the War Department G1 a transition to training and shipping out whole batteries and battalions to create cohesive units. The G1 replied to him that the Army would maintain the individual replacement system for administrative efficiency to meet its growing needs.

This practice of centrally assigning individuals continued after World War II with all its associated problems on morale and cohesion. The founder of sociology as an academic discipline, Émile Durkheim, argued that the increase in suicide in modern society was due to anomie—people becoming unmoored from their place in their community. After World War II, the Army emplaced a system of mandated moves every couple of years to ensure efficient manning. This system is a policy of enforced anomie. It is a probable cause for why, since 2011, even with investments into behavioral health services and the termination of combat operations, the Army’s suicide rate continues to increase. In seeking bureaucratic efficiency over putting people first, the Army breaks soldiers’ bonds of commitment to a “band of brothers” and breeds disenchantment.

The British and Canadian Armies still cultivate cohesion and commitment through their regimental systems—cohesion that eradicates anomie. Both armies also have lower suicide rates than the US Army. Over the last couple of decades, annual suicide rates per one hundred thousand soldiers were five in the Canadian Army, nine in the British Army, and twenty-eight in the US Army.

The cohesion of a regimental system also contributes to a greater dedication to long-term service. In 2022, 9 percent of the Canadian Armed Forces, 11 percent of the British Army, and 15 percent of the US Army separated from service. If the US Army had the retention rates of militaries with regimental systems, it would not face a recruiting crisis. With Canada’s retention rate, the US Army could maintain its current size with just 40,680 recruits a year.

In addition to increased commitment, cohesive armies are also more effective. Cohesion builds trust and initiative. When leaders know they will rely on the same subordinates for years, they will mentor them and invest in their development. Units that are together for years make long-term improvements to their systems and standard operating procedures. The bonds that soldiers develop over years of service build morale and create shared mental frameworks for their actions on the battlefield.

Before World War I, the French Army believed strongly in Ardant du Picq’s Etudes sur le combat, in which he stated that “Four brave men who do not know each other will not dare to attack a lion. Four less brave, but knowing each other well, sure of their reliability and consequently of mutual aid, will attack resolutely.” With such an understanding of the value of cohesion, their army fought bravely in World War I.

But in the 1930s, the French Army prioritized mass mobilization and firepower over cohesion in their doctrine of methodical battle, which took a scientific approach to war and treated their soldiers like interchangeable parts. In 1940, when French soldiers met the Germans at the decisive Battle of Sedan, they broke. The French commanders at the point of rupture blamed their men’s lack of will to fight on their lack of cohesion. On the other hand, German land forces had prioritized cohesion over bureaucratic efficiency. German recruits joined a specific regiment, attended basic training led by NCOs from that unit, and marched to the front to join their unit in company-sized elements. Due to their cohesion, they fought with initiative and courage.

A divisional system would also benefit the home front. It would allow families to stabilize and spouses to pursue careers. The Army will find it increasingly difficult to recruit and retain talented individuals whose similarly talented partners might naturally be unwilling to sacrifice their career for the Army. The antiquated assumption of the dutiful wife that follows her husband around is simply unreasonable and out of touch with today’s reality. This is not least because today’s Army has a mix of men and women in its ranks, unlike its World War II predecessor. Still, a little over 90 percent of Army spouses are women, and their experiences are indicative of a problem. Compared to the time of the AVF’s implementation, women have higher expectations for career fulfillment. In the 1960s, only 4 percent of women made the same or more than their husbands. Now, almost half do. A Department of Labor survey of military spouses showed that only 53 percent of Army wives participated in the labor market, many working transitory jobs on Army posts. They had three times the unemployment rate of women in the general population. In a 2021 Department of Defense survey, 48.3 percent of soldiers reported that the “impact of Army life on significant other’s career plans and goals” was an important reason to leave the Army, the second-highest reason soldiers consider leaving.

Decentralizing the Personnel System

Adopting a divisional system would allow the Army to implement the type of decentralized, flexible personnel system already used in the private sector and with Department of the Army civilians. Divisions could also be responsible for filling positions such as drill sergeants and recruiters, which would imbue them with a shared responsibility for ensuring competent soldiers arrived at their units. They would know that they would eventually go back to their divisions and serve with those new soldiers. Rather than relying on centralized decisions from Human Resources Command, divisions could fill vacancies by promoting from within or directly hiring from without. Without soldiers’ careers having to be easily legible for the centralized bureaucracy to make decisions, divisions could allow soldiers to follow flexible career paths.

Before World War II, soldiers could pursue diverse, flexible careers, driven by personal interactions. They had latitude to drive their own career paths. This latitude produced an officer corps that saw their profession as a calling. This corresponded to sociologist Max Weber’s ideal of a profession. He argued that “Unless we [as professionals] are working toward something specific, our actions aren’t anchored in any purpose of meaning.” Professionals obtain purpose through long-term commitment to solving a specific problem and by contributing to a professional body of knowledge.

Before World War II, flexible career paths in the US Army produced professional commitment and effectiveness. Janowitz identified that among the Army’s senior leaders during World War II, only 20 percent had followed a traditional career path, while 72.5 percent had followed an “adaptive” career path. As an example of the flexible career model existing before the war, Matthew Ridgeway taught Spanish at West Point for six years. Instead of traditional staff and command roles, he served most of the interwar years in Latin America and in the General Staff’s War Plans Division. His unconventional career produced an innovative and strategic mind, which Marshall recognized provided Ridgeway with enormous potential. He excelled as the commander of the 82nd Airborne Division without having done key developmental time at lower echelons. Before World War II, such diverse career paths were the norm for senior leaders, which created a diversity of thought at the top of the Army. Now such career paths are impossible.

To enable such career paths before World War II, officers like Ridgeway could go a decade without a promotion; there was no up-or-out system forcing soldiers out of service if they were not promoted on a rigid timeline. True professions do not use such counterproductive systems. Doctors are not forced out if they do not become hospital administrators. Professors do not lose tenure if they do not become department heads.

In a 1977 study of the AVF, RAND blamed the military’s attachment to the up-or-out system for preventing the transition to a long-term service model as the Gates Commission expected. During the draft era, the military tied experience to supervisory positions. It valued maintaining a pyramid rank structure required for managing draftees over developing experienced technicians.

The Army should allow soldiers to spend years becoming experts at a task. Imagine how effective a tank crew would be if they had trained together for five years or an advisor would be if he or she had worked with members of the same partner force for a decade, spoke their language, and knew their systems. By allowing such diverse careers before the 1940s, the Army produced effective leaders who were committed to their profession instead of careerists focused on efficiently moving through key developmental assignments.

End Corrosive Competitive Evaluations

By decentralizing the personnel system, the Army could eliminate corrosive competitive evaluations. The Army forces soldiers to compete against each other for their evaluations, a system that erodes professionalism and cohesion. In 1947 with DA Form 67-1, the Army implemented an evaluation system based in scientific management that forced evaluators to rank their subordinates against their peers. The Army desired a solution for centralized boards to reduce the number of senior officers as it cut down from its World War II size. This moved the service away from valuing an officer as a whole person. It eventually made NCO evaluations competitive as well. Before then, evaluations were qualitative. The Army diluted the competitive evaluation system in the 1980s and 1990s, but then sought to reinforce it as it cut down again in the mid-1990s. The strict box-checking system introduced in 2000 with DA Form 67-9 and quantitative numerations are the descendants of this scientific system to make the jobs of centralized promotion boards easier at the cost of fully appraising a soldier as a person.

Competitive evaluations are a discredited management practice. As The Economist reported, “Study after study suggests that they hurt overall performance, not least by lowering productivity. . . . Competitive ranking seems not just to reduce co-operation and foster selfishness but also to discourage risk-taking.” Groups that use them are less productive, have lower satisfaction, and exhibit increased status-seeking, careerist behaviors. The Army adopted them at the same time as American businesses in the post–World War II heyday of scientific management. But since then, General Electric, Amazon, Microsoft, and nearly all businesses that tried competitive evaluation systems have abandoned them due to their corrosive effects.

The Army needs to eliminate such practices. Competitive rankings facilitate centralized promotion boards but would not be needed if the Army used decentralized promotions managed within a divisional system. Divisions could do real talent management. Sitting on a divisional promotion board, decision-makers would know promotion candidates as individuals and not need to rely on numerical rankings.

The pressure of competitive ranking produces a workaholic culture that results in pervasive cynicism reflected across popular Army social media meme accounts. It is a work environment that drives people away. Before World War II, Army life was leisurely. It was a main draw and source of retention. The typical officer’s workday ended by noon. Officers averaged thirty hours of work a week. Such a schedule granted time for professional reading, writing, and mentoring. While the Army may not return to such a schedule, it should recognize that often the long hours that soldiers work are not to build true fighting capabilities but rather for theatrical displays of labor to outshine competing officers for that crucial “most qualified” evaluation rating.

The modern, high-pressure, careerist environment has not only undermined quality of life, but also degraded professional competence. Both Samuel Huntington and Janowitz praised the Army’s pre–World War II professional environment but worried about its postwar decline. Since the centralized personnel system was codified after the war, the Army has had a poor record in winning wars, it has shown little interest in learning from its defeats, and it has hazy thinking on how to fight future wars. By contrast, the old professional environment produced an Army that thought, invested in its soldiers, and won wars.

A Good Product Sells Itself

I do not propose a complete return to the pre–World War II personnel system, but a system inspired by its increased flexibility and commitment to long-term service. During the interwar years, the Army did not have decentralized promotions. It relied on centralized, time-in-service promotions that General Dwight Eisenhower testified to Congress were “unsatisfactory” and meant that “short of almost crime being committed by an officer, there were ineffectual ways of eliminating a man.” A decentralized system would not rely on time in service, up or out, or competitive evaluations.

Unfortunately, the Army continues to centralize decision-making with a drive for data-centric talent management, the latest buzzword offspring from the mid-twentieth-century’s scientific management. The Army needs to recognize that soldiers will not want to stay in an Army that treats them either as cogs in a machine or numbers on a spreadsheet.

The Army can take inspiration from its past to solve its manning crisis by returning to a professional, long-term service model. Such an Army would be more effective. It would reduce the amount of resources and soldiers committed to recruiting and basic training. It would have more committed soldiers and cohesive units that were not stuck in a Sisyphean cycle of retraining new arrivals. It would not have to recruit as many soldiers from a peacetime society with strong alternative opportunities to Army service. The Army must ask why it needs to churn through so many recruits. And, it needs to learn a good product sells itself. An Army that soldiers want to stay in will be an Army that society wants to join.

Maj. Robert G. Rose, US Army, serves as the operations officer for 3rd Squadron, 4th Security Forces Assistance Brigade. He holds an undergraduate degree from the United States Military Academy and graduate degrees from Harvard University and, as a Gates Scholar, from Cambridge University.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Christopher Hennen, US Military Academy at West Point