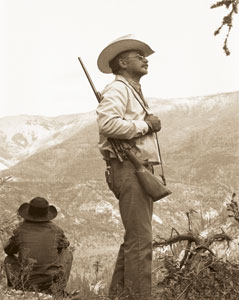

Skeeter wrote about handguns in Shooting Times for more than 20 years, but he was also an accomplished rifleman.

|

Among the most frequent complaints muttered by politicians is the one about having “labels” pinned on them. In other words, they dislike being confined; they want the freedom to move about. While I’m no politician, I sometimes find the label “handgunner” adorning my vest a bit too confining. Fact is, I’ve been a user of centerfire rifles for more than 40 years.

My first rifle, and the only one for a while, had belonged to my dad. It was a bulky, slab-sided Remington Model 8 in .35 Remington, and he had toted this cumbersome semiautomatic annually in the mule deer country of northern New Mexico since before I could remember. When he died, I was too young to go deer hunting by myself and had no one to take me, so I lugged it over the plains of Deaf Smith County, Texas, and plugged a few coyotes with it.

During World War II, ammunition was hard to come by. If you were a rancher or farmer, you were permitted to buy .22 rimfires, shotshells, and .30-30 rifle ammunition. My family farmed and ran a few cattle, and I got the allotment list at the hardware store, buying my full share of everything. Needing a .30-30 to use up my ration in that caliber, I traded for a beat-up old Marlin with a color-casehardened receiver and a halved penny for a front sight. I sometimes toted it horseback in a floppy saddle scabbard, but I don’t remember using it on anything except snakes.

My stint in the Marines began when the war was almost over. My first issue rifle was a new, in-the-cosmolene M1 Garand. This rifle had been made by Winchester. My partner, a high-school pal named Red Reeves, drew a Springfield Arsenal-made M1. Red was a good shot, but I thought I was better.

At the rifle range at Paris Island, South Carolina, I found my M1 shot out in the white to the right of the black at 100 yards with the windage knob cranked clear over.

My coach took his little wrench and moved the front sight so far to the right that it threatened to fall off the barrel. I was still printing right. He then told me to hold “Kentucky windage” and fire for qualification. I did, and I shot marksman. Red, of course, had no trouble and fired the platoon’s only expert score. I nearly died of humiliation. I was issued another M1 in Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, and took it to China. I never fired it.

Shortly after I returned home in 1946, the NRA handled DCM sales of surplus 1903 Springfields and 1917 Enfields. I bought a Springfield for about $17 and also took a friend’s Enfield off his hands. He’d paid $7.50 for it, and both rifles were in excellent condition. About the same time, I bought a .30-40 Krag in nice shape.

A friend who will remain nameless owned a lifetime supply of military .30-06 ammo. He was generous with it, and I got to work out the Springfield and Enfield constantly. I bagged a nice Canadian River gobbler with the Springfield and missed a shot at a mulie buck. I didn’t like the cock-on-close feature of the Enfield, and the Krag required store-bought ammunition, so I gave them up.

Using a pal’s loading press, I worked up a 180-grain .30-06 load, using then-new Hornady bullets and Hodgdon’s surplus 4895 powder. My Springfield had been semi-sporterized, and I managed to Indian up on a deer and introduce him to Hornady’s pride and joy.

I decided I needed a really deluxe rifle to go along with my several handguns. Gunsmith Potsy Baker offered to build one to my specifications, and his price was right. To get the funds for my basic rifle components, I had Potsy sell my dad’s Remington .35, my pet snubnose S&W Military & Police .38 Special, and a battered old Colt SA I kept as a spare.

Potsy used the proceeds to buy a commercial FN Mauser action, a Buhmiller barrel blank in .270 Winchester, and a premium-grade Bishop stock blank. As the work went on, I swapped for a Buehler one-piece scope mount, a new Weaver K4 scope, and a Timney trigger.

No speed demon, Potsy took a little more than a year to mold everything together. The result was a beautiful 8-pound .270 sporter that would stay inside a quarter at 100 yards. Before I got to try out this jewel on big game, I fell on hard times. I had to sell it for $205, which was a month’s pay back then. I’ve mourned it ever since.

When I entered the Border Patrol, I was chagrined to learn the issue rifle was the .35 Remington Model 81, a later version of my dad’s old Model 8. The armsroom in the Tucson sector headquarters held a rack of them, a rack of Reising submachine guns, some cased commercial Thompsons, and two or three Winchester Model 70s in .30-06. There was also one .30-30 Winchester Model 94 in a saddle scabbard. Buck Smith and I were the only Patrol Inspectors who rode horse patrol every day, and I decided to carry the .30-30, which had a great deal more ranging power than the issue Colt New Service .38 Special.

I prevailed on Gordon Pettingill, the acting chief, to issue me the .30-30 as a reward for passing probationary Spanish and law exams. I soon got tired of having to haul the carbine out of its scabbard every time I loaded the horses in the trailer or dismounted for a smoke. To have done otherwise would have been to court a broken riflestock, and I soon checked the .30-30 back in.

About this time, I learned that Ward Koozer, a master gunsmith then living in Douglas, Arizona, was converting .25-20 and .32-20 Winchester Model 92 lever actions into .357 Magnum carbines. I quickly acquired a nice .32-20 and sent it down to him, along with a handful of dummy rounds of my favorite .357 handload. When the gun was returned, it delighted me. I have owned several of these .357 carbines over the years, three of them converted by Koozer, and have been served well by them, both in law enforcement and in shooting game up to and including deer.

Back in Texas as a sheriff, I became interested in light sniper rifles and tried a custom .257 Roberts on a Remington action, as well as the first Model 70 Featherweight I ever saw. The Model 70 was chambered in .243; with it, I made the longest game shot of my life and dropped a buck antelope at a range so great I’m afraid to describe it.

At about the same time, I carried a “car gun” in a built-in zippered case attached to the front seat of my sheriff’s car. Much to the glee of my fellow officers, it was a large Winchester Model 86 lever action in .45-70. One neighboring sheriff laughingly offered to trade me two .30-30s for it, but there was no laughter the night I shot the fan off the car of two fugitives as they tried to run our roadblock. Their car quickly overheated and stalled, making them an easy catch.

In the middle ’50s, the DCM turned loose another bunch of 1903A3 Springfields, and I drew a new one. I had Dave Beavers of Hereford, Texas, cut the barrel to 22 inches and turn it to below standard sporter diameter. We replaced the stamped trigger guard and floorplate with milled ones and installed a custom safety and trigger. The stock was fashioned from a Fajen blank, and a full pistol grip was left on it. The scope was again a Weaver K4 (my idea of an all-around rifle sight). Caliber was left .30-06 (my idea of an all-around rifle caliber). The outfit weighs 7 pounds with sling.

I’ve had this rifle for almost 30 years, and it’s still a tackdriver. I have taken antelope with it, as well as whitetail deer in Texas and Mexico. It has brought home an abundance of mule deer from Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado. I packed it horseback into the wilds of northern British Columbia, and I used it to down a nice bull moose with one shot at 300 yards. It is my favorite rifle.

Everybody in the Southwest began shooting their rifles at metallic silhouettes a few years ago. This seemed the thing to do, so I equipped myself with a new Remington Model 700 in .308 Winchester, topping it with a Weaver K6 glass. I haven’t shot all the silhouettes I intended to, but my son Bart put a sleek spike mulie in the freezer with this one.

Ed Nolan of Sturm, Ruger & Co. presented me with a medium-weight Model 77 in .22-250 caliber some years ago. I installed it with a Weaver 3-9X variable and bought loading dies and bullets. I believe it is the most accurate rifle I’ve ever used. There are few prairie dogs around my part of the desert, but coyotes are here in force. I soon found it was no challenge to shoot coyotes with my .22-250. If they were still–or just fairly still–and I could see them, they were usually history. I gave the Ruger .22-250 to a Texas friend of mine who lives in prairie dog country, and it has found a home.

The great Vermejo Park Ranch in northern New Mexico is justifiably famous for its tremendous elk herds, and I hunted there a couple of seasons ago. A meat hunter, I’m not in the habit of looking for trophy heads, and a dry cow or a doe or a spike generally fills my needs to perfection. But something on this trip made me decide that nothing less than a six-point bull would do me. I’d never gone after an elk, and being determined to get the job done, I unlimbered my Ruger No. 1 .375 H&H Magnum. I conjured up some very accurate loads consisting of the Speer 285-grain Grand Slam bullet over a healthy charge of 4895. The Ruger shot like a show pony.

Within the first hour of the first day of my hunt, I jumped a small group of elk not 100 yards from me. I looked at them through the scope, resting the rifle on a fencepost, and found the crosshairs on the tail bone of a bull slowly trotting away from me. He was big and in good flesh, but he was only a five-pointer. I let him go and, of course, didn’t get another shot during the entire hunt.

I did take home an elk. Partner Evan Quiros gave me his rather than haul it all the way back to South Texas. It was, naturally, a six-pointer.

My Ruger Mini-14, my original Winchester 92 .44-40 short rifle, and my iron-sighted Ruger No. 1 .45-70 are all rifles that give me pleasure. I have quite a few more that are oiled and ready to go when the occasion demands. One is a Ruger Model 77 in 7mm Magnum. Maybe a cow elk will get acquainted with it this winter.

It’s said I’m a handgunner, pure and simple. My riflemen pals emphasize the “simple.” One day I’ll surprise them and write a story about rifles.