Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, one of the world centers of gunmaking was the Belgian city of Liège, which sits on the banks of the Meuse River in the country’s Wallonia region. Today, this city still remains a prominent part of the worldwide firearm industry, as it still is the home of one of the world’s most-recognized gunmakers, Fabrique Nationale.

But FN is one of the last surviving remnants of what was once a diverse and thriving gun trade that produced everything from common military muskets to some of the finest sporting arms of the age. One of the longest-lived companies producing fine guns in Liège was the firm of Auguste Francotte, founded in the early years of the 19th century.

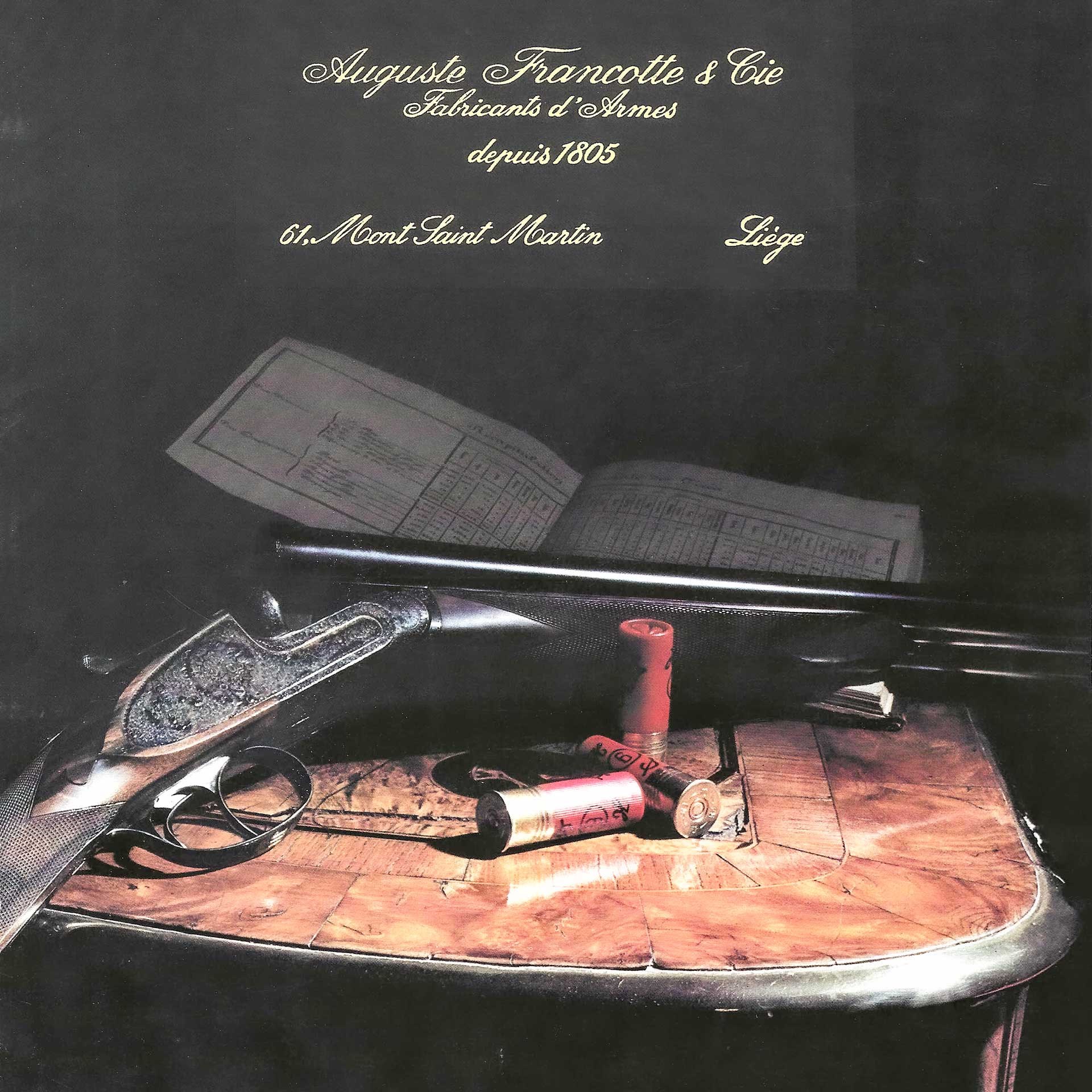

The cover page of A. Francotte’s 1990 catalog illustrates the company’s traditional approach to fine sporting arms. American Rifleman archives.

The cover page of A. Francotte’s 1990 catalog illustrates the company’s traditional approach to fine sporting arms. American Rifleman archives.

Like many Belgians in Liège, Francotte got his start in military guns, but turned to the production of fine sporting arms, which were produced by a highly skilled team of gunsmiths using traditional techniques. This traditional approach to gunmaking would remain a hallmark of the company and would continue to be the primary method by which Francotte sporting arms were made until the turn of the 21st century.

Remarkably, the Liège firm of A. Francotte would outlast many other Belgian makers, despite its adherence to traditional methods of manufacture. For much of the 19th century, guns were made by hand, with parts produced and fitted together by individual workers and gunsmiths into one-of-a-kind examples made to a general pattern. These parts could not interchange with parts in other guns, but by the end of the 19th century, production processes changed to meet the demands of military and commercial customers.

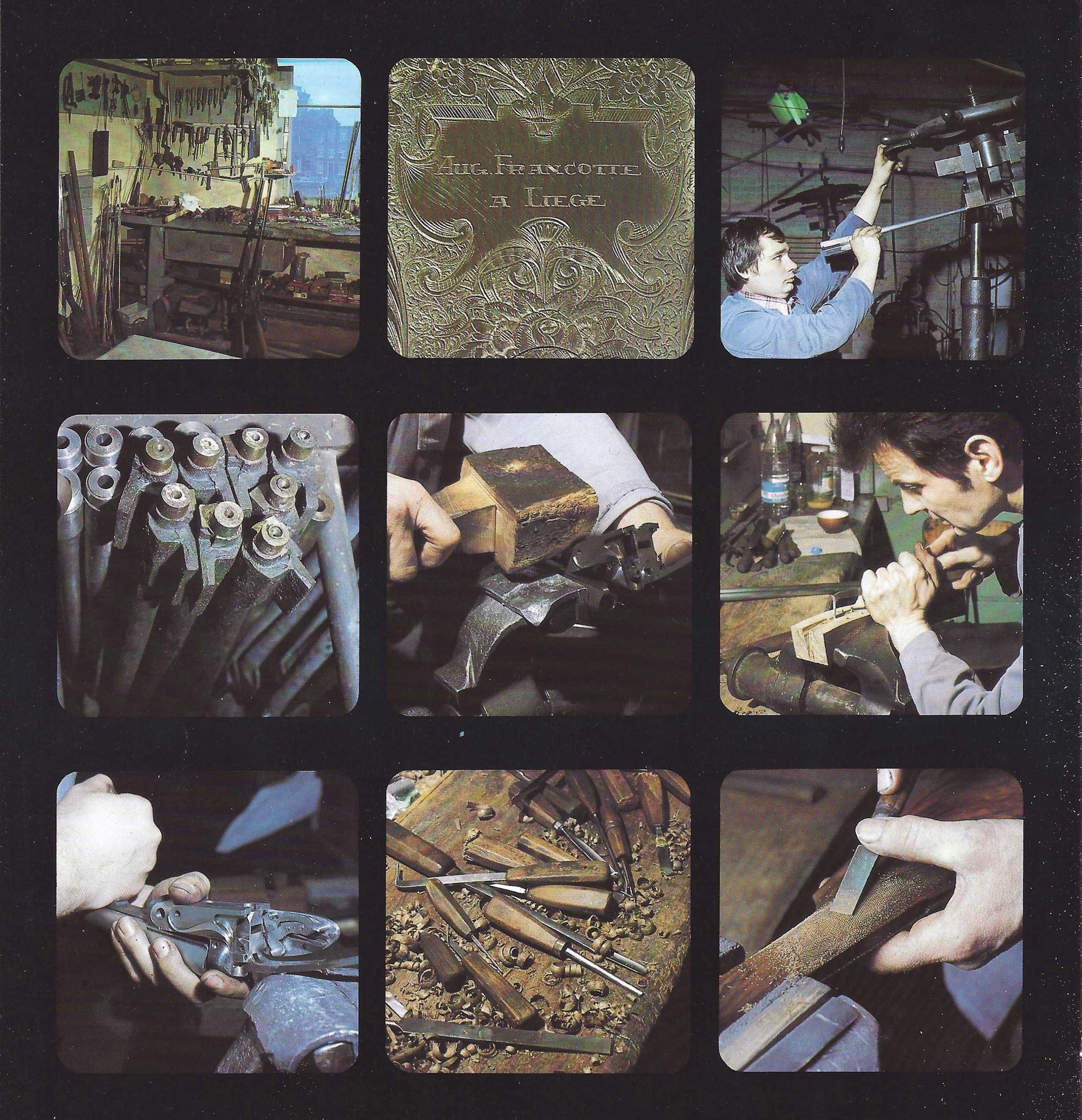

Even in the 1990s, Francotte’s gunsmiths used tools and techniques that were more familiar at the turn of the 19th century rather than the turn of the 21st century, as shown in the company’s marketing material. From American Rifleman archives.

Even in the 1990s, Francotte’s gunsmiths used tools and techniques that were more familiar at the turn of the 19th century rather than the turn of the 21st century, as shown in the company’s marketing material. From American Rifleman archives.

In 1889, an order placed by the Belgian government for 150,000 Mauser rifles led more than a dozen Liege manufacturers to band together, creating Fabrique Nationale d’Armes de Guerre, literally translating to “National Factory of Weapons of War.” Francotte was one of these 18 companies to contribute towards the modernization of Liège armsmaking, but when it came to its own arms production, processes remained traditional and slow.

Despite this, a market clearly remained for Francotte’s products, as the company outlasted other Belgian makers that folded as the 20th century unfolded. American Rifleman tested one of Francotte’s fine side-by-side shotguns in January 1991, noting that “the only failing we could find was that the Francotte doesn’t fit any pocketbooks here.” At the time, this “entry-level” Francotte sporting arm carried a suggested price of $18,000.

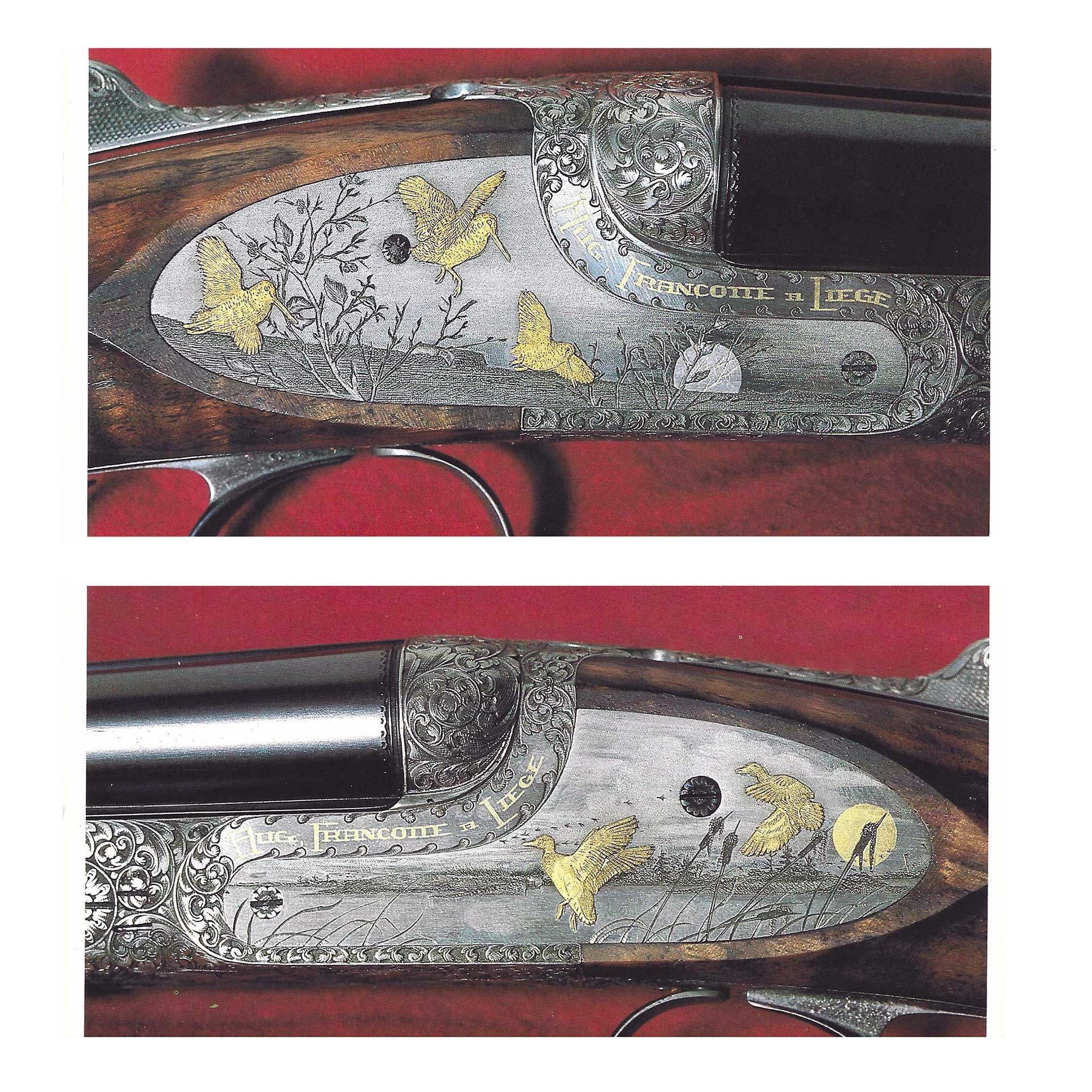

Whereas modern makers offered specific models of arms, Francotte remained entirely traditional. Each gun was crafted to the unique requirements of its owner, who could specify the type of action, caliber or gauge, style and length of barrels and any number of options and embellishments. While a basic Francotte could be had for $18,000, guns with custom features and engraving could cost as much as $80,000 in the early 1990s.

As expensive as the guns could be, by the end of the millennium, Francotte was still producing about 100 fine sporting arms a year, but the business struggled. By the mid-20th century, competition from other makers who could produce finely built, yet more affordable, arms put pressure on the business. The Francotte family sold the company in 1973, but fierce competition from builders in England and Italy continued to hamper sales. By the end of the 1990s, only three employees remained.

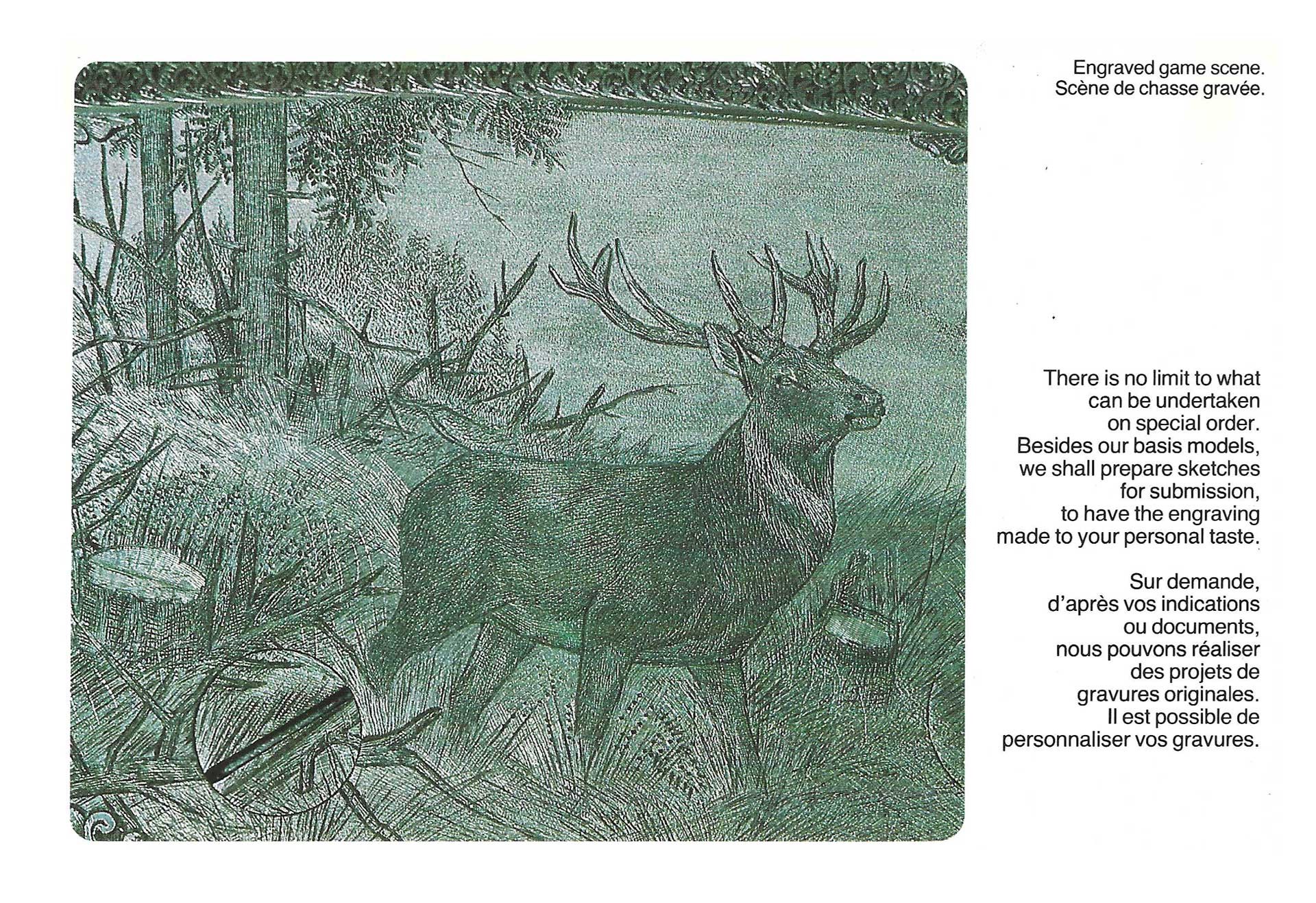

Even up to the company’s dissolution, Francotte’s marketing materials illustrated the skill with which its team of gunsmiths and engravers could approach fine arms manufacture, as illustrated by the hand-engraved game scene shown above. From American Rifleman archives.

Even up to the company’s dissolution, Francotte’s marketing materials illustrated the skill with which its team of gunsmiths and engravers could approach fine arms manufacture, as illustrated by the hand-engraved game scene shown above. From American Rifleman archives.

In November 1998, Tom Derksen, a Dutch entrepreneur and former professor of psychology, was an avid hunter who bought the Francotte firm in an attempt to save it from dissolution. In 1998, Derksen told the Dutch-language magazine Trends that staffing had increased to nine employees, and that he was optimistic about the future of the company.

“The demand for handcrafted shotguns is increasing every year,” he told the publication (translated from the original Dutch). “You can compare the trend with that in the watch or car industry. There, too, you see an increasing demand for increasingly beautiful, increasingly exclusive products.”

Despite Derksen’s optimism and the modernization of Francotte’s production, which had begun to incorporate machine-made parts into its traditional system of production, by 2001, the company had closed its doors, leaving a legacy of fine sporting arms that still graces the collections of hunters and sport shooters around the world.