PFC Martin Oldham had forgotten what it meant to be human. He had landed on White Beach 2 on Peleliu some 18 days before and was amazed that he was still breathing. The things he had seen in those 18 horrible days would haunt him forever.

PFC Oldham’s life was reduced to the moment. In the daytime he tried to become one with the filthy island and avoid catching a bullet or frag long enough to get through another day. Nights were pure hell. The Japanese would infiltrate American lines and kill Marines in their foxholes. Proper sleep was simply not an option.

Nearly 20 days’ worth of continuous combat had stripped away the veneer of civilization. His uniform and boots were rotting on his body, and his existence was distilled down to the next tactical objective or the next low spot in the ground. He had little thought of home or family. He focused completely on the task at hand.

The pillbox had been hidden in a stubby black hillside. The Japanese sited the blasted things like artists, and they were adjacent the firing port before it opened up. Seven of Oldham’s fellow Marines fell before somebody got close enough to toss a satchel charge inside. Oldham scampered around to the back and emptied 15 rounds from his carbine through the rear access door. At the sound of silence and against his better judgement, curiosity made him poke his head inside.

They typically tended to these things with flamethrowers, so it was a bit unusual to see how the Japanese had lived before the Marines tore them to pieces. In this case, the cramped interior of the fighting position reeked of violence. As Oldham turned to leave he noticed a pistol in the dim light. He pried the elegant little weapon out of the dead fingers of the Japanese officer who had been its previous owner and took it with him. It was two days before he had time to study the thing.

The gun was shopworn but functional. It looked vaguely like a German Luger, but the action was clearly different. PFC Oldham cleaned the weapon and then locked it away in his foot locker back in the company headquarters area. If he lived to get off of Peleliu he would have a nice souvenir. However, there was no time to fret about that now. For the time being he just threw himself back into the full-time job of not dying.

Ballistic Philosophy

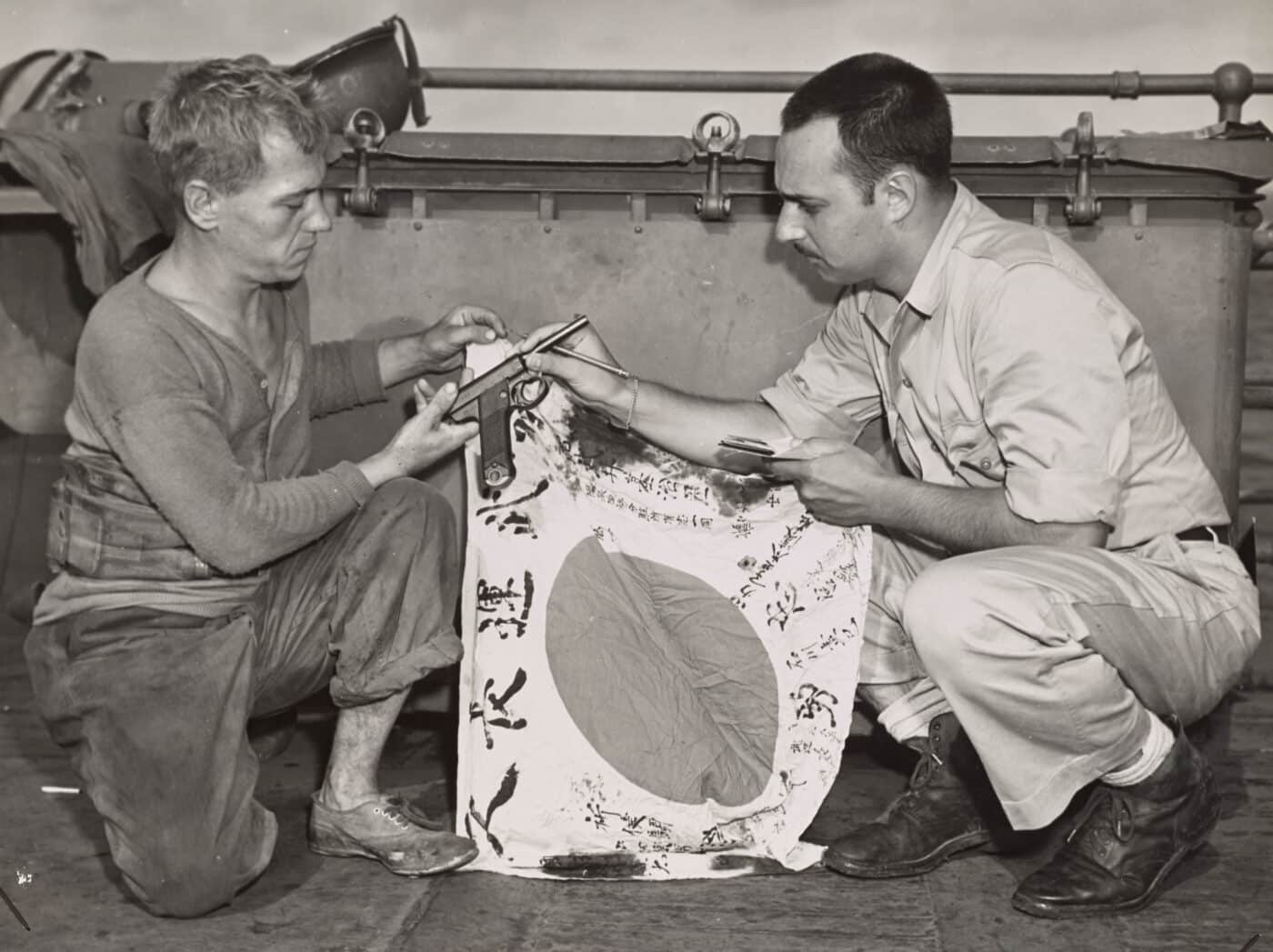

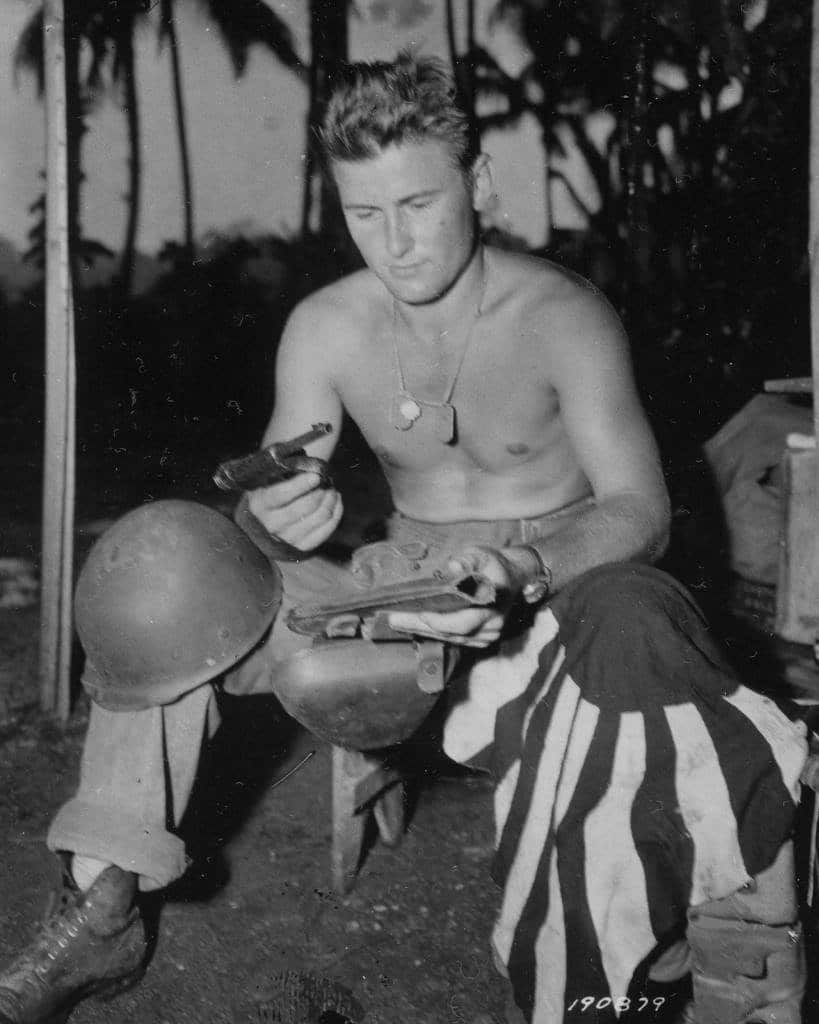

During World War II, it was said that the British fought for King and country, the Japanese fought for their emperor, the Germans fought for Hitler and the Americans fought for souvenirs. It’s in our natures to covet mementos from remarkable times in our lives. Combat during World War II was the most remarkable thing most of the young men who lived it would ever experience.

We were not quite so tense about such stuff back then. If a soldier or Marine wanted to keep a gun, all they needed was the signature of their company commander authorizing the bring-back. I have a full-auto Japanese Type 99 paratrooper machine gun that made it home with just such a piece of paper.

Many G.I.s just didn’t bother and tucked the guns away in sea bags and footlockers for the covert trip home. In fact, a “duffle bag cut” in the stock of a captured rifle reflects an effort at shortening the gun’s components adequately to hide inside a duffle bag. Among the many potential combat souvenirs taken during the Pacific War, few were more coveted than the Type 14 Nambu Pistol.

The Type 14

The Type 14 was produced in five different variants starting in 1904. It is named after Kijiro Nambu, the most prolific Japanese gun designer of the day. While the weapon had a variety of obvious flaws, it was indeed quite advanced at its time of introduction.

At a glance, the Type 14 does look very similar to the German P.08 Parabellum pistol designed by Georg Luger. Like the Luger, the grip-to-frame angle is more pronounced than that of the P.38, 1911 and most other combat pistols of its day. However, the two weapons are completely different inside.

The Type 14 is a recoil-operated, locked-breech design that fires the relatively anemic 8x22mm bottlenecked cartridge. This novel little round is only slightly spunkier than the .380 ACP. The military 8x22mm loading pushes a 102-gr. bullet to just north of 1,000 feet per second out of a pistol barrel. The Type 14 feeds from an eight-round box magazine that rides in the butt. The Type 14 charges from the rear via a knurled knob and ejects directly upwards.

Practical Tactical

The trigger on the Type 14 is longer and mushier than it should be. The German Luger is comparably cursed. The safety is a generous swinging lever mounted to the left side of the frame. The safety rotates through a full 180 degrees when activated. It cannot be reasonably utilized with the firing hand alone.

The bolt assembly locks to the rear on the last round fired. However, there is no provision for a bolt catch on the pistol. Once you remove the magazine the bolt flies forward of its own accord. At that point, you insert a fresh magazine and jack the bolt back again smartly to get the gun back into action after it runs dry.

The left-sided magazine release looks like it should work well, but nobody’s fingers are both that short and that limber. Additionally, the magazines do not drop free but rather must be manhandled a bit to remove. There is an ample serrated baseplate provided on the bottom of the magazines for just this purpose.

Overall, the soft recoil produced by the modest 8x22mm cartridge combined with the Type 14’s elegant lines made it a very shootable pistol. While it was perhaps not as effective as the American 1911 for down-in-the-dirt gunfighting, the Type 14 was thoroughly serviceable for its intended purpose. The Japanese viewed handguns as more a badge of rank and status than a practical combat tool. A Japanese officer’s pistol was designed to keep his troops in line and administer the coup de grace during executions, not clear structures of entrenched hostiles.

Denouement

The Japanese ultimately produced around 400,000 Type 14 Nambu pistols in all its several guises. By contrast, we built around a million M1911A1 handguns during WWII. However, in the final analysis none of that mattered.

Pistols don’t win wars. They are actually fairly infrequently used for their intended purposes on the battlefield. A soldier’s handgun is usually more talisman than combat tool. In this regard, the Japanese Type 14 Nambu pistol did just want it was intended to do.