Rudy Augarten wasn’t a war junkie, but he certainly found his share of war. Augarten flew P-47 Thunderbolts for the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II. He was shot down over Normandy in 1944 and captured, but ultimately escaped. He then returned to his unit to fly and fight some more, eventually logging more than 90 combat missions. Like countless other American veterans, once the war was over he went home secure in the realization that he had helped rid the world of a vile scourge. However, events brewing in the Middle East were conspiring to put him back in the cockpit of a warplane yet again.

In the aftermath of the world’s bloodiest conflict, the British were ready to divest themselves of some of their more fulminant holdings. I’ll spare you a discourse on the political details, because I frankly do not understand them all that well myself. Regardless, on May 14, 1948, the Israelis acted at the end of the British Mandate for Palestine to declare independence and establish a free-standing state. The following day a military coalition of Arab nations including Egypt, Transjordan, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen declared war.

This was a time of profound desperation for the burgeoning Israeli state. Bereft of serious weapons and stifled by suffocating arms embargoes, they faced the combined organized militaries of seven nation states. Things looked grim, indeed. However, these people were still reeling from the Holocaust and were frankly tired of being pushed around. The stage was set for a proper scrap.

Most of the world opposed them, but the Israelis were understandably driven and well-funded by expatriates overseas. One of the critical components of their early national survival was Operation Velvetta. Also known as Operation Alabama, this was the mission to obtain fighter planes for the nascent Israeli Air Force. The narrative reads like a movie script.

In 1948, Europe was still a wasteland. Amidst the pervasive detritus of global war, Jewish clandestine operatives secretly purchased 60 surplus British Spitfires for $23,000 apiece from Czechoslovakia. After surreptitiously sneaking them into the country, they were destined to join a handful of former-Luftwaffe Messerschmitt Bf-109’s and a smattering of P-51 Mustangs. A short three weeks later on October 16th there were still only ten fully operational fighter planes in the entire country. Some two dozen volunteer fighter pilots had answered the call to man those planes. Rudy Augarten was one of them.

On October 19, 1948, Rudy Augarten was at the controls of a freshly imported Spitfire alongside his wingman, Canadian Jack Doyle. The previous day Augarten had downed an Egyptian Spitfire while at the controls of an Israeli Bf-109. Now Augarten and Doyle were patrolling high above the Negev Desert looking for trouble. Off in the distance they found it in the form of four Egyptian Spits flying in formation.

Outnumbered two to one while flying identical machines, Augarten and Doyle still had a singular advantage. They were a product of the American and Canadian fighter pilot training system. This made them capable, aggressive and competent. Carefully rolling around to put the sun behind them, the two Israeli pilots each picked a target and opened up with their 20mm cannon. The first two Egyptian fighters fell trailing smoke and exploded on the desert floor below. The Israelis damaged the other two Spits before returning to base for fuel and ammo.

Rudy Augarten ultimately downed four enemy aircraft while flying for the newly minted Israeli Air Force. One of his kills was in the Bf-109, two in the Spitfire, and the last at the controls of an Israeli Mustang. Only one other Israeli pilot matched his score. After the war, Augarten remained in Israel to help train the next generation of Israeli aviators. He then returned to the States to complete his college degree at Harvard University. Following his graduation he returned to Israel once again and dug out his old IAF uniform. He spent two years in command of the Ramat David air base and eventually retired as a Lieutenant Colonel.

The Plane

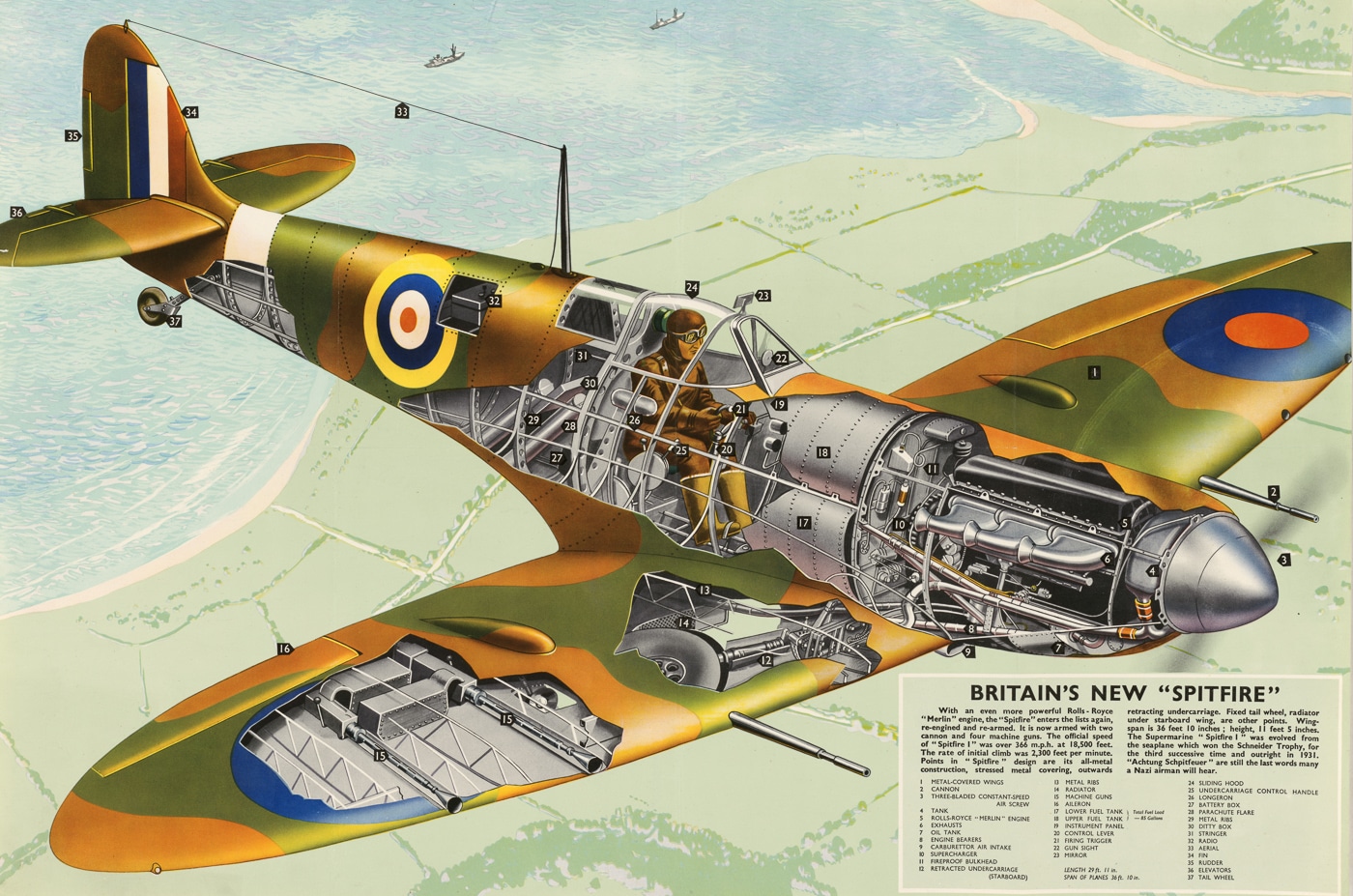

The competitive performance of the Supermarine Spitfire during the Israeli War for Independence illustrates the unique nature of the design. The Spitfire first flew in 1936. During the course of the war it went through 24 successive Marks. Some 20,351 were built. The Israelis got their first copy in 1948.

Twelve years is an absolute eternity in the world of combat aircraft development, particularly during the maelstrom that was the Second World War. However, the Spitfire remained competitive with other machines from start to finish. The basic airframe lent itself to drastic upgrades in both engine power and armament. Few other fighter designs have been so versatile.

The Spitfire was originally designed as a short-range, high-speed interceptor by R.J. Mitchell, the chief designer for the Supermarine Company. The most iconic aspect of the Spitfire’s design was its graceful elliptical wing. Designed to be both thin and strong, this geometry, though fairly difficult to produce, greatly enhanced the plane’s performance.

The original Spitfires sported a 1,030 hp Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. The final Marks featured a Rolls-Royce Griffon producing 2,340 hp, more than twice the output of the original powerplant. Such flexibility speaks to the extraordinary nature of the design.

The graceful semi-monocoque, duralumin fuselage was a bear to build in quantity. The architecture included multiple compound vertical curves that complicated production. The plane’s metal skeleton was built around nineteen separate formers that spanned from behind the propellor to the tail along with fourteen longitudinal stringers and four longerons. Mass production was facilitated by a series of jigs that kept everything in place during assembly.

The landing gear of the Spitfire folded outward and resulted in a narrow ground track. While the narrow track gear on the Messerschmitt Bf-109 has been rightfully maligned, that of the Spitfire is not much wider. However, the Spit’s landing gear deployed into a near-vertical state that was much stronger than that of its German counterpart.

Early Spitfires carried eight .303-caliber Browning machineguns adapted for open-bolt operation. Later Spits were armed with four 20mm Hispano autocannon. Interstitial models carried combinations of these two weapons. A few even incorporated American .50-caliber guns as well.

Impressions

I have actually had the privilege of flying a Spitfire myself. The big 1,600-hp Merlin engine of the one I flew produces a throaty rumble that is simply breathtaking to behold up close. The long nose and conventional landing gear layout conspire to impair visibility on the ground. This means the pilot must S-turn while taxiing to keep the plane pointed in the right direction.

Once in the air the plane is almost too cool to describe. The Mk IX will reach beyond 400 mph, well over twice the top speed of most civil prop-driven aircraft, without breaking a sweat. The Spitfire accelerates very quickly in the dive, and it’s natural agility will ruin you to lesser craft. The cockpit layout and instrumentation are surprisingly crude by modern standards. Rolling inverted in a vintage Spitfire is an incomparable rush.

There are around 70 Spitfires remaining in flyable condition today. Brad Pitt owns one he bought for a cool $3.3 million. If I ever win the lottery and find myself with some serious change burning a hole in my pocket, Brad is the first guy I’m going to call. Perhaps he’s grown tired of his.

Thanks to www.flyaspitfire.com for the opportunity to