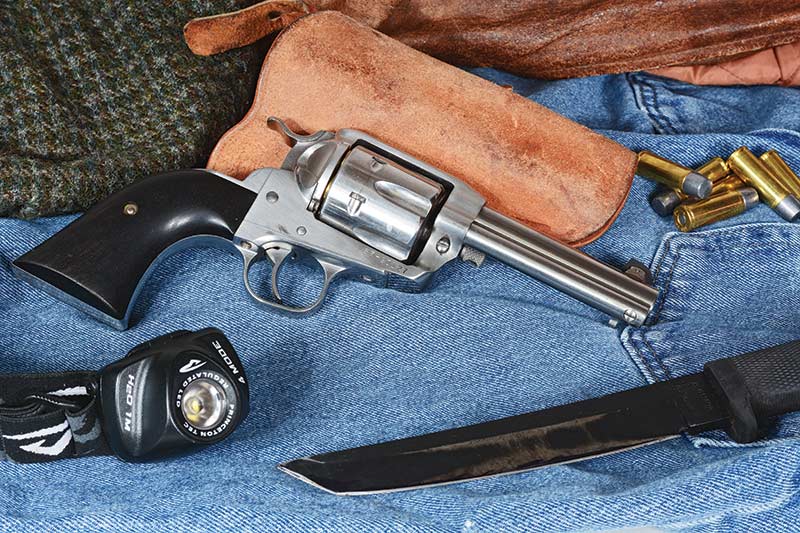

Jeremy’s Vaquero, customized by Hamilton Bowen and the star of many adventures.

I saw the two green points shining back at me in the beam of the headlamp I’d just turned on — but it wasn’t until I made out the dark bulk behind them I realized what was on the side of the trail ahead. Living and hiking in the mountains, I’d seen this shape before. “Bear,” I thought to myself. Not good, but not the end of the world.

Then, in the bluish light of the LED, I saw a black catlike form scramble up the tree behind her. I can see it now, still hear the scratching sound her cub’s claws made on the bark as it clambered up — whether it actually made such a sound in the moment or not. What I don’t remember is pulling out the big stainless sixgun or laying the wide Bisley hammer back over a cylinder-full of 335-grain hardcast solids.

A Rock And A Hard Place

It was my first time out bowhunting and when darkness caught me miles away from my car, I’d disassembled the takedown recurve and stowed it in my pack. I then walked down the closed gravel road in the dark, the gray of the road and the dark blue of the sky standing out enough from the black woods to keep me headed the right direction without a light. I’d hiked quite a bit in the dark and except for my family giving me a hard time, I’d never really given it much thought. At least until a little voice in the back of my head — you know, the one telling you you’re wrong — told me to turn on the light.

I backed off to give Mama Bear room and considered my options. There was a trail behind me splitting off to head north, the wrong direction, and dead-ended several miles away at a state road on the far side of a mountain. I looked at my phone: no service, no way to call for a ride even if I hiked the several miles uphill to get there.

Ahead of me, the ground fell off downhill to the left side of the road — where she was — and rose steeply, impassable, on the right. There was one way out and it went right past where Mama Bear had staked her claim.

The Gun

I bought the Old Model Vaquero almost 20 years ago when it was just a Vaquero, alongside my old college shooting buddy who bought its twin from a gunshop whose doors are now closed. Polished stainless steel, with 4¾” barrels, faux ivory grips and chambered in .45 Colt, the two sixguns were one digit off from being sequential serial numbers. Close to broke, we bought a single box of 20 cartridges and split them. I promptly took my new thumb buster — loaded with the last six rounds from the box — with me to Mississippi when I went to see my grandfather.

Grandad

Born in California to a veteran of the Spanish American War, my mother’s father was raised in a rambling way, growing up in Kentucky and Florida before settling in Mississippi, but he never lost his love of the West. His house — more specifically, his studio, where he painted and where my cot was usually stationed when we visited — was fascinating from the powder horn and barbed-wire collection on the wall, to his oil lamps and the Winchester I always begged him to show me. I don’t remember what he said about my Vaquero but I know he approved.

If I have any doubt about it, I can look around my own office at his Stetson up on the top of a bookshelf or the couple pairs of rattlesnake rattles and a foil-wrapped packet of .30/30 cartridges I inherited from him.

Nonetheless, the Vaquero remained a bit of a novelty for a few years while I mostly shot M1911s until I snagged a writing assignment on Bowen Classic Arms and dropped the Vaquero off with Hamilton. Returned with a fine, brushed finish, the newly lightweighted gun now had a 4″ barrel, useable front sight and a low, fast-cocking Bisley hammer. The grips were replaced with Persinger ebony grips made in El Paso and fitted to the newly decked frame. It was almost too pretty to shoot.

Almost. I put several hundred rounds of Black Hills and Hornady through it but never quite mastered the gun. What I didn’t understand at the time was how much grip consistency affects accuracy with a single-action, where the gun is recoiling through your hand as the bullet exits the barrel.

Grip it hard, the bullet goes low; loosely, it goes high. I finally learned this about 10 years ago, when I made the decision to put a thousand rounds each through three guns I didn’t shoot all that well. After enough weekly or twice-weekly trips to the range, depleting the large stock of ammo a friend had loaded for me on his Rock Chucker, I could finally hit consistently with the big Ruger, gleefully slamming 255-grain SWCs into my steel spinner until it cracked. At the insistence of another shooting friend, this one from law school days, I shot my first cowboy action match with it. I placed an enjoyable second to last, just ahead of him.

Loading Up

By then I wasn’t afraid to scuff the Vaq up anymore and after a couple less serious encounters of the ursine kind, I decided the extra power of +P .45 Colt rounds was preferable to the .45 ACP I usually carried in the woods. At Bowen’s advice, I stoked it with Grizzly Cartridge Company’s 335, which I chronographed at a freight-train like 1,089 fps.

And there it was, in my hand, cocked. I was the most scared I’ve been in my adult life, more scared than riding shotgun at Road Atlanta in a Porsche racecar dropping down Turn 12 at a buck-twenty, more scared than when I was serving legal papers on people, alone, in downtown Atlanta as a law student, more scared than walking down the stairs in the dark for the first time holding my newborn son.

Shaken But Not Stirred

Scared, but not shaking. With no other option, I breathed a prayer, short and packed with condensed intensity, and began my one-step-at-a-time trip past Mama Bear, now out of sight on the other side of the brush lining the road. Desperately not wanting to shoot this bear, I had decided if she charged I would fire a warning shot first to try to turn her. Considering the extremely short distances involved — 20 feet or less — the decision likely would have cost me a mauling, if not my life.

She let me pass, but followed me through the dark for a hundred yards. At some point I’m sure I gently lowered the hammer and re-holstered but it was no time soon. In the car on the way home, I called my mother who’d long been worried about my hiking habits. “I think it’s time to re-evaluate my decision-making paradigm,” I said drily.

Still Here

The old Vaq is still loaded with 335s, their big, broad meplats almost flush with the end of the cylinder — fresh ones, of course. There’s a little play in the cylinder now, which is striped with irregular lengthwise scratches from many trips in and out of its holster. There are some fine cracks in the grain of the ebony, too, and if you look closely I’m sure you can find a dull red speck or two in the crevices of the dovetailed front sight where it’s hard to wipe the moisture out. This after all the times it’s been rained on, alongside with me.

Sometimes when I pick it up, I think of my grandfather long since passed on to his reward, or my other friends — the one with its partner who moved to Texas and largely out of my life, the other who had lost his vision and with it his dreams of cowboy shooting.

And those two bright green eyes — I think about those a lot.