At Rock Island Auction Company, we are no strangers to historic weapons owned by some of the biggest names in American and world history. Just last year we sold the Napoleon garniture, Alexander Hamilton’s Revolutionary War flintlock pistols and epaulets, a pair of Remington revolvers attributed as presented to “The Great Liberator” Alexander II of Russia, and John Wayne’s Colt Single Action Army to name just a select few.

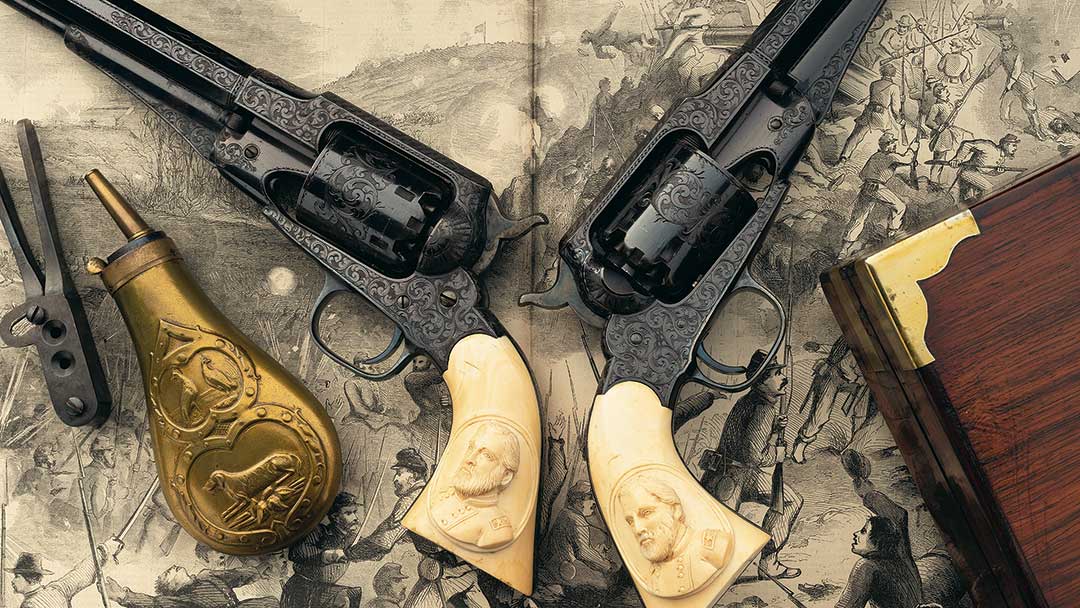

These timeless pieces are always an absolute thrill to work with and research, but while we all get very excited to see what they bring, it can be hard to watch them go too. My grief, however, is soon quashed by the next round of legendary artifacts to come through the door, and today’s topic presented a real historical treat: an astoundingly beautiful pair of Remington New Model Army revolvers with raised relief carved grips featuring busts of General Ulysses S. Grant that were presented to him during the Civil War. This cased set has it all: condition, rarity, artistry, and fascinating historical connections. It is sure to turn heads and is certainly expected to set a new record for the most expensive Remington revolvers ever sold

Given Grant’s immense significance as a Civil War commander and later as president from 1869 to 1877 during Reconstruction, items owned by Grant are naturally among the most desirable 19th century American artifacts, particularly those from the Civil War. They are tangible connections to one of the United States’ most iconic military leaders and to the Union cause. Ulysses S. Grant’s historic presentation engraved Remington New Model Army revolvers available for sale in Rock Island Auction Company’s May 13-15, 2022, Premier Auction are arguably the most historically significant and valuable Remington firearms of all time and certainly must be considered a “Holy Grail” for Civil War collectors.

These revolvers were presented to Grant in the latter half of 1863 or early 1864 and were hidden from public view for over a century and a half until they surfaced only a few years ago when put on display at the Las Vegas Antique Arms Show in January 2018. The set and their history were discussed in detail in the article “General Grant’s Magnificent Set of Lost Remingtons” by the late firearms author S.P. Fjestad published in the National Rifle Association’s American Rifleman. Fjestad wrote, “Without a doubt, these cased Remingtons constitute the most elaborate and historically significant set of currently known revolvers manufactured during the Civil War.”

“Unconditional Surrender” Grant

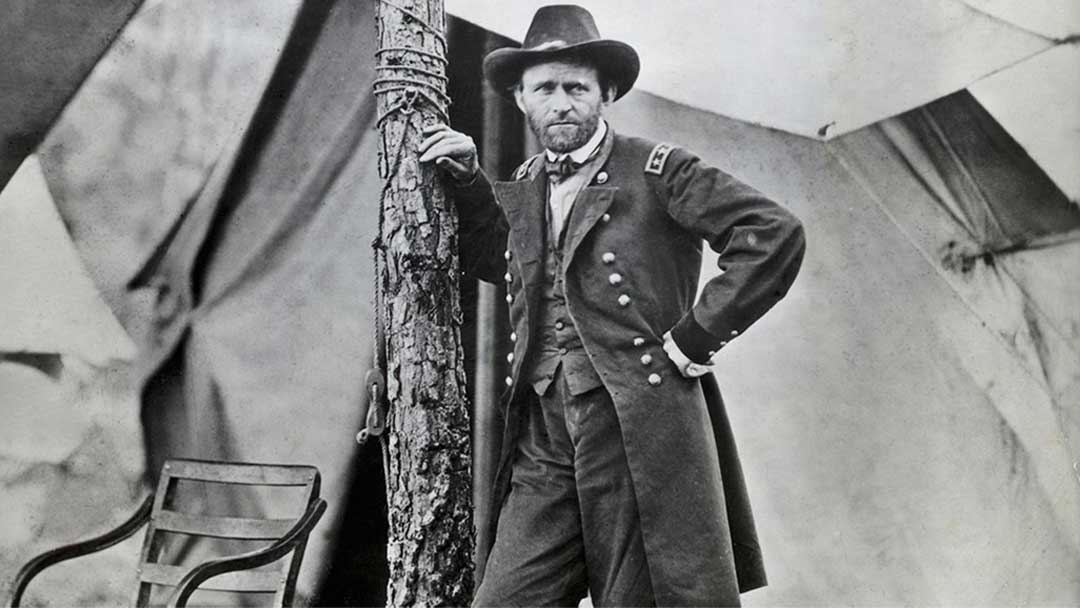

In terms of famous 19th century Americans, you can’t do much better than Ulysses S. Grant, and as a man with Illinois ties, he is particularly exciting for those of us here at Rock Island Auction. Grant rose from relative obscurity to the heights of power and international fame. He was the second American after only George Washington to become a lieutenant general and the first American to become General of the Army, and his success on the battlefield propelled him to the White House as the 18th President of the United States.

His birth name was actually Hiram Ulysses Grant, but Representative Thomas L. Hamer incorrectly listed his name as Ulysses S. Grant when he nominated Grant for West Point. There his new “U.S.” initials earned him the nickname “Sam” after Uncle Sam. After graduating in 1843, he was assigned to the 4th Infantry stationed at St. Louis, fought in the Mexican-American War, and earned a reputation as a man who was brave and could fight.

After the Mexican-American War, Grant hit hard times and resigned in 1854 because he had taken up drinking to console himself while separated from his family. He lived in his “Hardscrabble” cabin near St. Louis and attempted to get by as a farmer. He had a slave named William Jones that helped out on the farm, but the Grant family did not support slavery, and he manumitted Jones in 1859 despite his own desperate finances. After other failed business ventures in St. Louis, he finally accepted his father’s invitation to work at the family’s tannery in Galena, Illinois, in 1860 on the eve of the Civil War.

The “War Between the States” propelled Grant to national fame, but he did not begin the conflict as a well-known figure outside of those that knew him from West Point and the Mexican-American War. Many of his former comrades were fighting against the Union. One of them, Confederate General Richard Elwell, is quoted as saying, “There is one West Pointer, I think in Missouri, little known, and whom I hope the northern people will not find out. I mean Sam Grant. I knew him well at the Academy and in Mexico. I should fear him more than any of their officers I have yet heard of. He is not a man of genius, but he is clear-headed, quick and daring.” The North found Grant thanks to his service in the Western Theater of the war. He was initially the colonel of the 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry, hardly a position to make a name for himself, but that soon changed.

Grant displayed remarkable leadership from the beginning of the war and a real willingness to fight and secure victory. At Fort Donelson, in Tennessee, Grant defeated the Confederates and informed Confederate commander John B. Floyd that “No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.” Floyd agreed, and Grant earned the moniker “Unconditional Surrender Grant” and secured arguably the first significant Union victory of the war. Grant gained national attention, including that of President Abraham Lincoln, for his victories in the West, and he became Lincoln’s hand-picked commanding general of the U.S.

Grant was not everyone’s pick to lead due to accusations of drunkenness and the cost in blood of his tactics, but Lincoln liked Grant as a commander because he was aggressive. The president felt other Union commanders were too cautious and thus failed to secure victories and destroy the Confederate armies. When other Union generals called for Grant’s removal as commander of the Union Army of the Tennessee, Lincoln is famously reported to have remarked, “I can’t spare this man; he fights.”

L.D. Nimschke’s Masterpieces

The revolvers Grant received are true works of art on “steel canvases” and excellent examples of the idea that “not all art is framed” as you often hear at Rock Island Auction Company. Without any connection to Grant, these revolvers would still be among the most desirable of all Remington revolvers. While no signature has been found on this pair of revolvers, the author is confident in the identity of the engraver: iconic 19th century Master Engraver Louis D. Nimschke of New York. This has been confirmed based on comparison to another pair of historic Remington revolvers recently sold at Rock Island Auction Company in the May 2021 Premier Firearms Auction: the pair identified as made for presentation following the visit of the Russian fleets to the United States in 1864 (special serial numbers 8 and 11 while Grant’s are 1 and 2). That pair was signed by Nimschke, with his trademark “N,” and is recorded in his famous pull-book in detail. The patterns on both Grant’s revolvers and the Russian presentation pair are extremely similar overall. The barrel engraving on Grant’s revolvers also matches other designs from Nimschke’s pull-book providing further proof.

The majority of the exceptional engraving on these revolvers consists of Nimschke’s iconic scroll engraving patterns with punched backgrounds and floral accents. The top straps have twisted or entwining rope patterns along the sides of the sighting grooves where the Russian presentation pair featured chain designs. The Columbia’s patriotic stars and stripes pattern shield is located behind each hammer followed by “FROM YOUR FRIENDS/O.N. CUTLER. W.C. WAGLEY.” down the back straps. The left grip of the first revolver and right of the second revolver features an excellent raised relief carved eagle, flags, and Columbian shield patriotic motif that was also used on the grips of the Russian presentation revolvers. The opposite sides feature the significant and beautifully executed raised relief carved busts of General Ulysses S. Grant. This historic set comes in a deluxe rosewood presentation case with a suite of accessories.

Grant’s uniform on the carved grips displays the insignia of a two-star general (major general). Grant attained this rank in the volunteers in 1862 after he captured Fort Donelson and then became a major general in the regular army in the fall of 1863 after he secured Vicksburg. Grant was again promoted on March 2, 1864, to three-star general (lieutenant general). These ranks and dates, plus the introduction of this model in 1863, suggest the revolvers were presented to Grant in the latter half of 1863 or early 1864 after he captured Vicksburg on the Fourth of July in 1863 and thus secured the length of the Mississippi River for the Union. The exact date, location, and circumstances of the presentation of the set remains unknown; however, the inscriptions on the back straps match the inscriptions on a pair of Colt Model 1861 Navy revolvers (11756 and 11757) also manufactured in 1863 and presented to General James B. McPherson. Together, these inscriptions provided clues about the revolvers’ history.

Grant and the Cotton Trade

The pair was presented by Otis Nelson Cutler and William C. Wagley. Fjestad concluded this incredible cased pair was “a ‘thank you’ for a wartime cotton-smuggling scheme,” and that Cutler and Wagley most likely ordered these revolvers through Schuyler, Hartley & Graham of New York City and that they then contracted Nimschke to execute the remarkable embellishment. While period sources, including newspapers, Senate records, and Grant’s own papers, definitely link Grant and McPherson to Cutler and Wagley via the cotton trade in 1863, Grant’s participation is likely not as nefarious as Fjestad’s comments imply, but such an incredible pair inscribed from businessmen working in Union controlled territory in the South certainly sounds like a bribe. Like the claims of corruption that dogged Grant as president, the truth is more complicated and unlikely as dark as his detractors suggest.

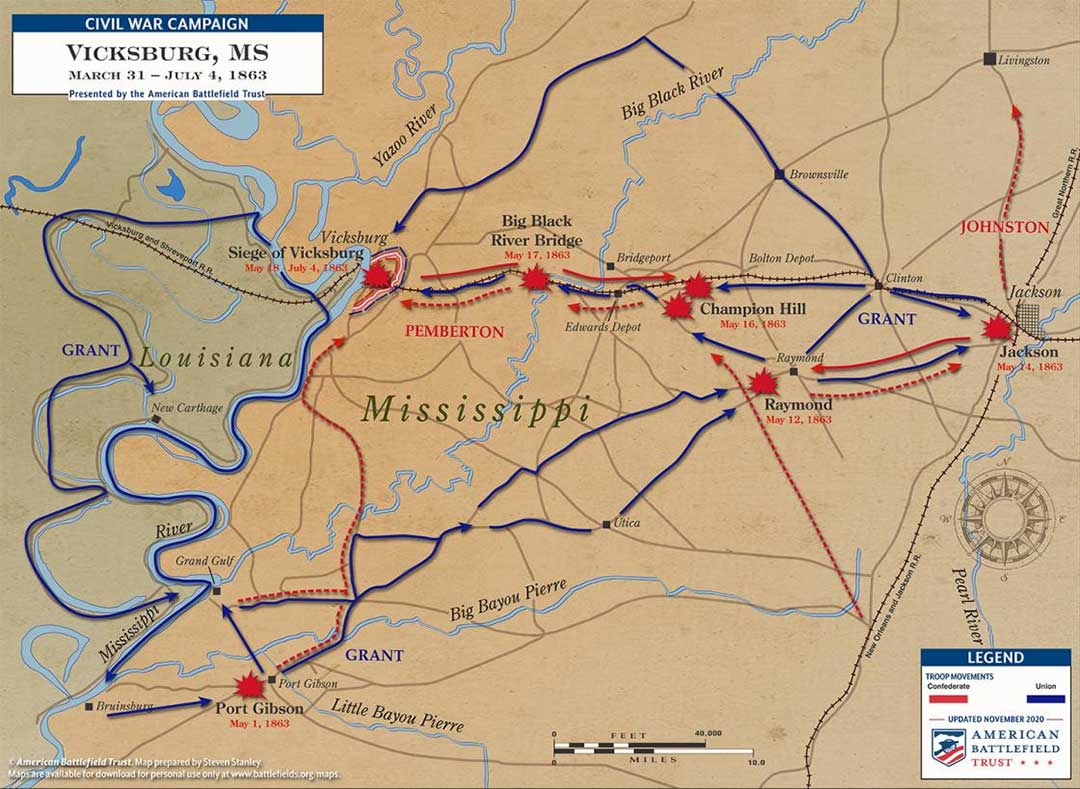

By 1863, Grant was already a Union hero following his famous victory at Fort Donelson in February of 1862 along with the triumph of the Army of the Tennessee over the Confederacy at the bloody Battle of Shiloh in April of 1862. His victories gave the Union control of the northern stretch of the Mississippi River, and the capture of New Orleans on May 1, 1862, gave the Union control of the mouth respectively. However, the Confederacy still retained control of Vicksburg, disrupting Union use of the river. The fortified city on a bend in the Mississippi became the main target for Grant, and its capture had the potential to end the war.

The river was the crucial mode of transportation for the region, including for the lucrative trade in cotton. While cotton was a leading cash crop in the South, it was also a vital raw material for northeastern industry. Grant established programs putting runaway slaves to work in camps picking cotton that could be shipped up river and sold to fund the Union war effort and to produce needed supplies. This plan, approved by President Lincoln, for moving the cotton out of the South under Union contract was also designed to help prevent the South’s most valuable cash crop from being used to fund the Confederate war effort. The workers were compensated for their work, and some of the proceeds were also used to provide them with food, clothing, and shelter.

The legal trade provided cover for illicit trade, and there were widespread reports of bribes and corruption. Cotton in Union controlled territory was regulated by Union officers and agents of the U.S. Treasury. Grant and his officers were in charge of granting licenses for his district. The Secretary of War was told, “Every colonel, captain or quartermaster is in a secret partnership with some operator in cotton; every soldier dreams of adding a bale of cotton to his monthly pay.” Though many Union officers were corrupt and profited through involvement in both legal and illegal trade in cotton during the war, evidence shows that Grant found the whole business to be an annoying distraction from his primary military objective: capturing Vicksburg.

Grant’s own father actually came down river with two businessmen intent on getting a contract for cotton and splitting profits. Had Grant been inclined to corruption and self-dealing, he certainly could have played along. Instead, he was furious and sent the men back north as soon as he learned of their plans. In response to all of the corruption surrounding cotton in his district, Grant also gave his most controversial order in late 1862: General Order No. 11. Under this order, Jewish residents were expelled from Grant’s district because he blamed them in part for the illicit cotton trade. The two men that had travelled with his father happened to be Jewish. Lincoln eventually reversed the order after outcry, but not before many Jewish residents had been expelled. Frustrated with dealing with the cotton trade, Grant moved to significantly curtail it all together.

News reports from the period provide important evidence for both Grant’s efforts to limit the cotton trade and his connection to the men who presented the revolvers in early 1863. The Daily Missouri Republican on February 18, 1863, noted: “It is unfortunately too true that many of our officers have been unable to resist the wonderful temptation of the cotton trade. The demoralization has been well nigh checked below by the orders of Gen. Grant, which will not allow any cotton to be shipped North, nor even bought, until Vicksburg is taken.” Coincidentally, this article appears next to one of the advertisements for “Remington’s Army & Navy Revolvers.”

Who were Cutler and Wagley, the men who presented these revolvers? Both Cutler and Wagley were Mexican-American War veterans: Wagley was a 2nd lieutenant in the 3rd Dragoons, and Cutler was an orderly sergeant and captain in the 1st Massachusetts Volunteers. After the Mexican-American War, Cutler formed a company of men to explore for gold in California and then built a home on the family farm in Lewiston, Maine. He was later contracted for the building of the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad in Missouri and moved to Hannibal where he became the superintendent of the railroad. Cutler was assigned as a special treasury agent stationed at New Orleans at the end of the Civil War, and Wagley was active in the river trade in Louisiana and continued captaining steamboats running to Mobile and Montgomery in at least 1865 and 1866.

The Nashville Daily Union on April 25, 1863, in an article from “Correspondence of the Cincinnati Gazette. Young’s Point, LA., April 7.” about “King Cotton” directly references both Grant and Wagley. The article notes that Grant had announced he would not allow cotton to go upriver until Vicksburg was taken but that some cotton was being shipped nonetheless. “A Breckenridge Democrat, whose loyalty is like that of the Enquirer, has had a contract for picking and bailing cotton in the vicinity of Lake Providence (Louisiana), – This gentleman, Wagley by name, who hails from Warsaw, Ill. Has most emphatically ‘struck ile.’ How much cotton he has sent North, I do not know, but I do know that five hundred bales are now awaiting shipment at Lake Providence and Berry’s Landing. It is a matter of comment that his cotton has been gathered already baled, from the plantations in the vicinity, and that not one-tenth of it is really picked and ginned under his superintendence. Another individual of the same stripe had nearly succeeded in getting a similar contract for the region in the vicinity of Gen. (John Alexander) McClernand, but his plan was overthrown by that officer himself. He is now endeavoring to obtain an order from Gen. Grant over Gen. McClernand’s head, and it is feared that he will succeed.”

Grant’s own papers provide more details of direct cooperation with McPherson and Wagley: “On April 1, [Grant] wrote to Capt. Ashley R. Eddy. ‘The cotton detained by you one half of which was for Government and the other for Mr. Wagley is a part of some cotton abandoned in the field and picked by Mr. Wagly [sic] under an arrangement made with him by Genl McPherson. The one half can be released to Mr. Wagley.’…When William C. Wagley wrote that Col. William S. Hillyer, provost marshal at Memphis, threatened to seize his cotton, (Lt. Col. John) Rawlins endorsed the letter. ‘This contract was made by with Mr. Wagely [sic] in the utmost good faith and must be respected. You will therefore not interfere with shipment of cotton by seizures or otherwise, unless you pass satisfactory evidence of a violation of the contract on Mr Wagely’s [sic] part, mere suspicions will not suffice.’”

This provides a clear link between Grant, McPherson, and Wagley’s role in the cotton trade, but what about Cutler? Senate documents include an additional important report for the context of this cased set that ties all of the men together: “The Committee on Claims, to whom was referred the claim of O.N. Cutler, have examined the same and submit the following as their report:” It states that William C. Wagley later identified as a citizen of Illinois had a March 5, 1863, contract signed by Assistant Quartermaster John G. Klinck “for picking, ginning, and bailing of cotton then growing on the lands about Lake Providence, in the State of Louisiana, which had been abandoned by the rebel owners and occupants, and then lately brought within permanent Union lines by the advance and occupancy of the federal forces. This contract was approved by Major General McPherson, commanding that district.”

The report notes that half of the cotton was to be government property and the other half Wagley’s and that Wagley would be allowed to have his cotton shipped by the government to Memphis. On April 3, Wagley assigned his interest over to O.N. Cutler of Hannibal, Missouri. Cutler then delivered “a large amount of cotton” at Lake Providence and took his assigned half. General Grant had his quartermaster seize Cutler’s cotton to use it to protect the machinery on the steamer Tigress for a run of the Confederate blockade at Vicksburg. Captain Benjamin F. Reno recorded this amounted to 268 bales. Cutler claimed they weighed 113,900 pounds in total and had a total value of $62,645. The report concludes with a recommendation that $50,000 be appropriated by Congress to pay for this seized cotton in 1868.

This evidence clearly demonstrates that Grant and McPherson were involved in at least one valuable contract for southern cotton that served to net Wagley and Cutler considerable profits. It also shows that Grant actually seized at least one shipment of cotton as part of his efforts to capture Vicksburg. Grant’s revolvers may have been specifically presented in response to his capture of Vicksburg which gave the Union essentially full command of the Mississippi River and would have opened the river up to more trade and reduced the risks for men like Wagley and Cutler shipping cotton and other goods up and down the river. While no documentation has been found detailing when and where Grant and McPherson were presented their sets of revolvers, the information at hand certainly suggests that Wagley and Cutler presented the Union generals their respective pairs as a thank you for their assistance in the cotton trade.

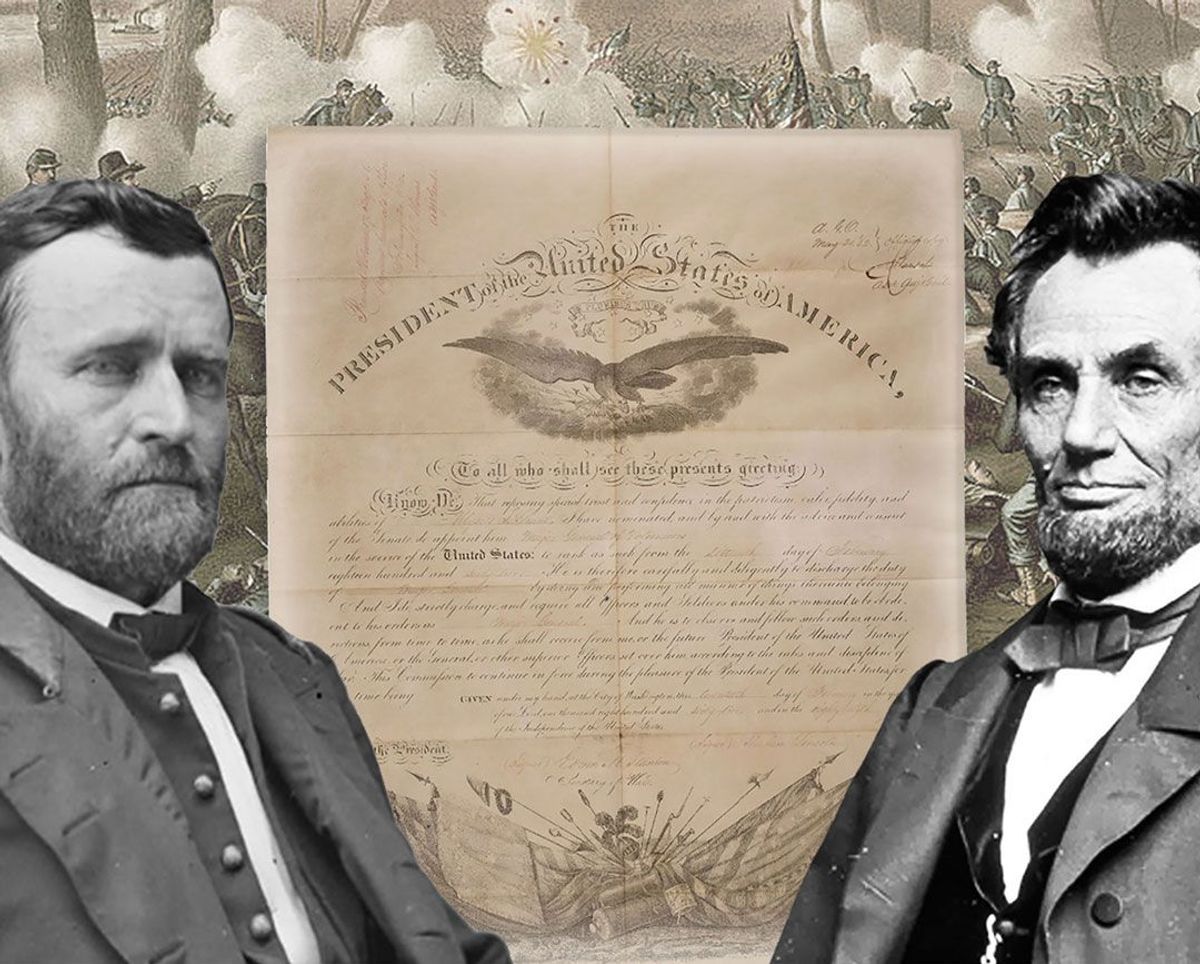

On the Fourth of July, 1863, Grant’s forces captured Vicksburg and General John C. Pemberton’s approximately 30,000 strong army. The day prior, Pickett’s charge had been repulsed at Gettysburg, and Robert E. Lee’s army limped back to Virginia. Together, the Union victories in the East and West marked the ascent of the Union’s fortunes and the decline of the Confederate cause. Grant was promoted by President Lincoln to major general in the regular army and given command of the new Division of the Mississippi on October 16, 1863. His decisive victory in the Chattanooga Campaign in November opened the South up for attack. On March 2, 1864, Grant was promoted to lieutenant general and given command of all of the Union armies. Grant was formally commissioned by Lincoln on March 8 in a Cabinet meeting and worked more closely with the president for the remainder of the war. With Grant in charge, Lincoln expected Union forces to relentlessly pursue and defeat the Confederacy and finally bring the bloody war to a close.

Ending the War and Reuniting the Country

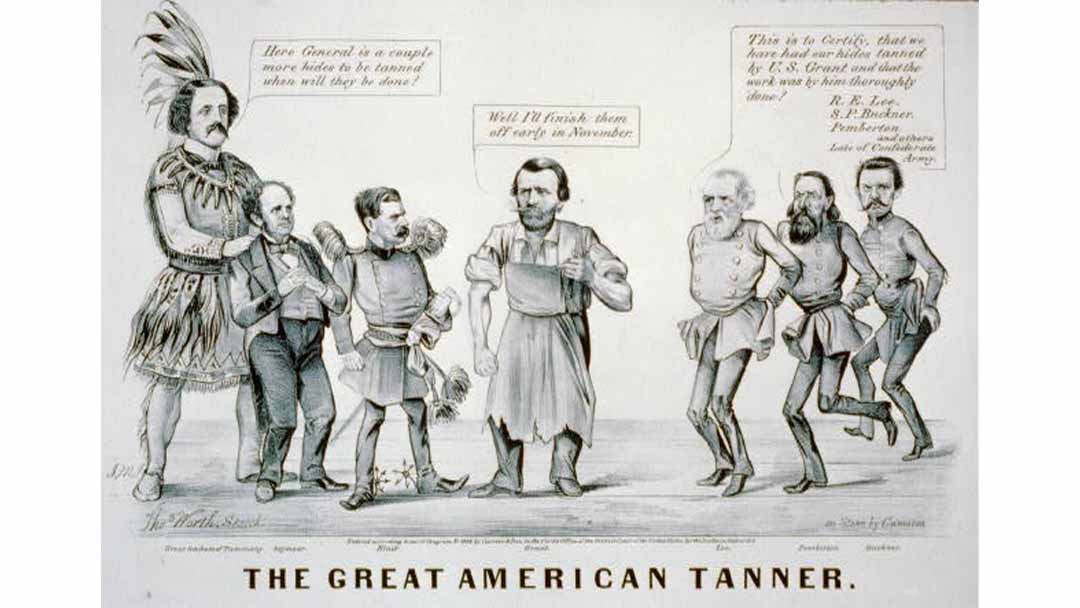

Grant directed the Union armies in pursuit of Robert E. Lee into Virginia and worked towards capturing the Confederate capital at Richmond and Petersburg to the South. He kept his men in near continual contact with the Confederate lines and slowly wore them down at a great cost in blood on both sides. Petersburg and Richmond finally fell into Union hands on April 3, 1865. Lee retreated with part of his army to fight another day, but Union victory in the war was close at hand, and Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House less than a week later on April 9. Grant’s terms of surrender were rather lenient for Lee and his men, including parole and a guarantee that the men were “not to be disturbed by U.S. authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.” Grant saw this as the end of the war. As such, the former Confederates were now their countrymen again, not the enemy. He even allowed the Confederates to keep their sidearms and horses and helped provide Lee’s bedraggled men with much needed provisions.

Most of the remaining Confederate resistance ceased by the end of the month with Joseph E. Johnston’s surrender on April 26, 1865. The final surrenders were completed a month later. By securing victory for the Union, Ulysses S. Grant provided the basis for reunification and established himself as a national hero. He remained commander of the armies as the country began reconstruction. Grant was further honored on July 25, 1866, when Congress promoted him to the newly created rank of General of the Army of the United States. Grant broke with President Andrew Johnson over the latter’s “Presidential Reconstruction” policies that were soft on former Confederates and did not protect the rights of African Americans and Republicans in the South, but Congress stepped in and guaranteed Grant’s control of the U.S. Army by passing the Command of the Army Act. After Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was illegally fired by Johnson, Grant was briefly appointed as interim Secretary of War but stepped aside when Congress reinstated Stanton, and Johnson was soon impeached in relation to the whole affair and narrowly escaped conviction.

In 1868, Grant was unanimously nominated by the Republican National Convention as the party’s candidate for president and won the election. As president, he oversaw “Congressional Reconstruction” and the ongoing Indian Wars in the West. He sought to aid southern Republicans and African-Americans through additional legal protections and by deploying the cavalry back into the South to counteract the Ku Klux Klan and other lawless groups. Though he succeeded in winning a second term in office, claims of corruption and other scandals diminished Grant’s power in the South. Renewed conflict with Native Americans following their mistreatment also undermined his earlier peace efforts in the West. He initially declined to run for a third term and instead returned to civilian life in 1877 for the first time since the outbreak of the Civil War, but he made an unsuccessful run for the Republican nomination in 1880.

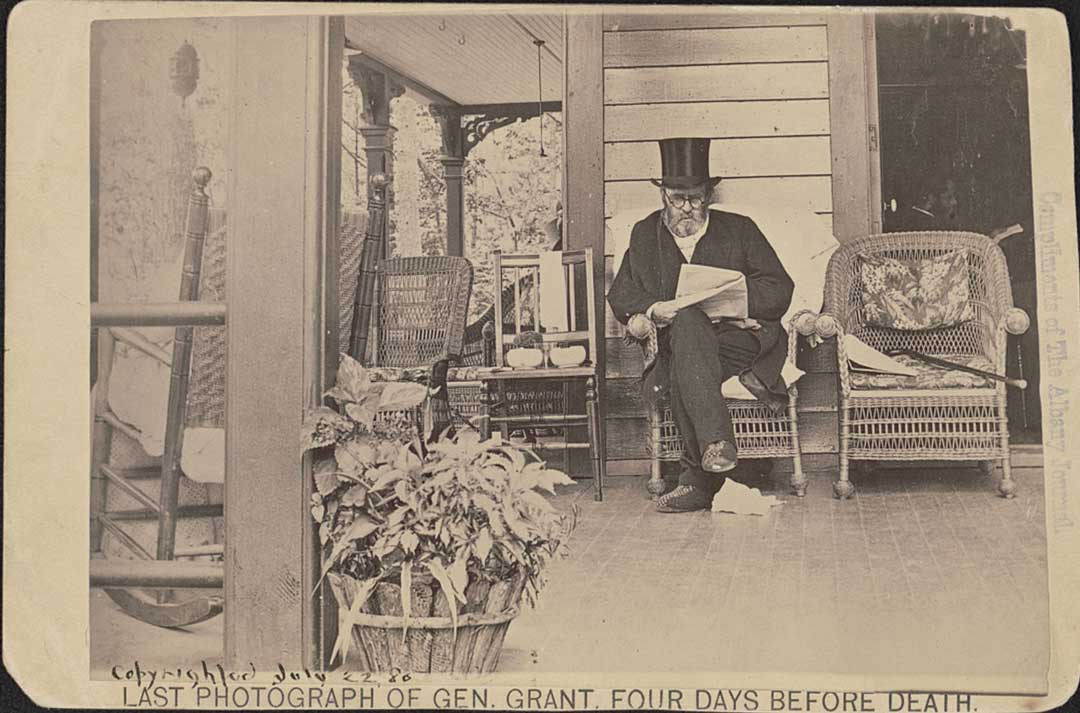

In 1884, Grant’s wealth was destroyed by a scheme executed by his business partner Ferdinand Ward. Grant had risen from poverty and obscurity once before, but his time was running out: he was diagnosed with throat and tongue cancer that fall. He sold many of his valuable Civil War relics in the 1880s to pay his debts. However, these incredible Remington New Model Army revolvers remained with the Grant family for decades. Grant may have already given the pair to one of his sons. Though destitute, Grant remained a popular figure, and his friend Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain, pushed him to write his memoirs. Grant poured all of his energy into writing his autobiography while he could to ensure his wife was not left a destitute widow and very likely also to restore his name. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant was completed in 1885 just before his death and was published in two volumes through Clemen’s new publishing firm Charles L. Webster & Company. The company also published Adventures of Huckleberry Finn the same year. Grant’s autobiography became an instant American classic and is certainly worth the attention of any student of Civil War history. The proceeds of the book benefitted the Grant family, and the publication’s success also helped solidify Grant’s enduring legacy as the hero who led the Union to victory. In his memoirs, Grant wrote that the Confederate cause was “one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse,” but he also noted that he believed the Confederates truly believed in their cause and recognized their bravery and suffering in the long fight for it.

This phenomenal pair of revolvers are believed to have been brought to California in the late 19th century by either Ulysses Grant Jr. or Jesse Grant II. The two brothers ran the U.S. Grant Hotel in San Diego together in the early 20th century. Jesse Grant II was the last surviving child of General Grant and died in 1934. His second wife, Lillian Grant, saved many of the Ulysses S. Grant artifacts and passed them on to Ulysses Simpson Grant V, likely including the cased pair. The cased set left the family’s possession when it was reported to have been given as payment by U.S. Grant V to a handyman who worked on the Jesse Grant II home (also known as the Julia Grant home since his mother also lived there). The handyman kept the revolvers for many years before his family was eventually convinced to sell the revolvers in 1976 to a collector. Documentation from the sale of the revolvers by the Reynolds family to Frank L. Hatch are included with the revolvers, and an affidavit from Richard Hatch, the former’s son who was present for the sale, is also included stating that the revolvers had been received as payment by Bill and Mel Reynold’s father for work on the “Grant House” in San Diego. He identified the house as the Grant house at 6th and Quince.

When these revolvers were sold in 1976, none of the individuals involved would have known who the men on the back straps were or that they were connected to Ulysses S. Grant via the cotton trade in Union controlled territory in the South. Their new owner began researching his carefully guarded treasures and had found some evidence of the cotton traders’ connections to Grant by the time of his death in 1987, but the revolvers and their connection to the great Union general remained hidden from the public. After his passing, the revolvers remained with his wife. Their son Richard inherited the pair upon her death in 2013, but the pair remained concealed for another five years. In 2018, they finally saw the light of day when they were put on display in Las Vegas.

Now, for the very first and possibly last time, this pair of incredible Civil War presentation Remington revolvers with beautiful engraving by L.D. Nimschke and grips carved with busts of General Ulysses S. Grant are publicly available in our upcoming May 13-15 Premier Firearms Auction where they are estimated to sell for $1 million to $3 million.

Sources:

S.P. Fjestad, “General Grant’s Magnificent Set of Lost Remingtons” https://www.americanrifleman.org/content/general-grant-s-magnificent-set-of-lost-remingtons/

H.W. Brands, “The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses Grant in War and Peace” (New York: Anchor Books, 2013), 188.

Rock Island Auction Company, Rock Island Auction May Premier Auction Volume II (Rock Island: Rock Island Auction Company, 2021), 122-127.

R.L. Wilson, “L.D. Nimschke: Firearms Engraver” (Rochester, NY: Rowe Publications, 1992), 19 and 25.

Letter from Charles A. Dana to Edwin Stanton on January 21, 1863, printed in “The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies,” Series I, Volume LII, Part I – Reports, Union Correspondence, Etc. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1898), 331.

Grant’s controversial order and his reaction to his father’s plans have been discussed at length in many articles and books, including Jonathan D. Sarna’s New York Times “Opinionator” piece “General Grant’s Infamous Order” from December 19, 2012.

Nahum S. Cutler, “A Cutler Memorial and Genealogical History…” (Greenfield: E.A. Hall & Co., 1889),461-462.

Ulysses S. Grant, “The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant Vol. 7: December 9, 1862-March 31, 1863,” ed. John Y. Simon (Carbondale and Edwardsville: University of Illinois Press, 1979), 328-329.

F. & J. Rives and George A. Bailey, “The Congressional Globe: Containing the Debates and Proceedings of the Third Session Fortieth Congress…”(Washington, D.C.: Office of the Congressional Globe, 1869), 1592-1593.

Ulysses S. Grant,” Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant Volume 2” (New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1886), 488-489.