For people of a certain age who grew up during the Golden Age of TV westerns in the 1950s and ’60s, practically every television station in the country was broadcasting the sounds of multiple gunshots and the clattering of galloping hooves that heralded the arrival of a diverse group of tall-in-the-saddle heroes whose dexterity with firearms became legendary among viewing audiences.

But no matter who received top billing in these horse operas, as they were called, the real stars of the shows for many of us were the guns that were used by the actors. Gun’s like Hugh O’Brian’s Buntline Special in “The Life And Times of Wyatt Earp” and Steve McQueen’s Mare’s Leg, a fantasized chopped-down Winchester 92 with a nine-inch barrel.

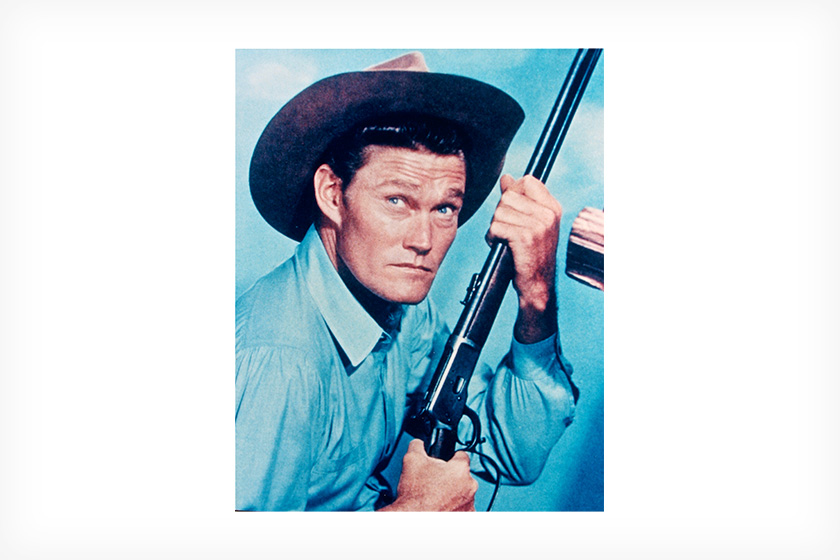

Another Winchester 92 that achieved an iconic level of fame was the loop-lever carbine that was rapid-fired and spun so deftly by Chuck Connors “The Rifleman,” which aired on ABC from 1958 until 1963. In his starring role as Lucas McCain, Connors was seen at the beginning of every show cranking off a seemingly endless fuselage of shots with his saddle-ring carbine. After he spins it, he tosses it from his right hand to his left and inserts a new cartridge while staring menacingly into the camera.

This rapid-fire exhibition entailed no trick photography. Connors actually was that fast and agile with his carbine, having been a former athlete who played both professional basketball and baseball in the major and minor leagues before turning to acting. But in his starring role as “The Rifleman,” he had a little help with a special tricked-out Winchester 92 carbine that featured a wide loop lever so that it could be spun like a pistol.

But The Rifleman’s carbine had an extra touch that made Chuck’s rapid-fire prowess possible without the risk of plunging the trigger through his finger while working the lever so swiftly: a screw that protruded through the trigger guard and could be adjusted to trip the trigger every time the lever was slammed home. Thus, his trigger finger never enters the trigger guard. This screw could also be backed out so the carbine could be fired in a normal fashion.

In addition, to enable the actor to spin-cock his carbine without having the cartridge tumble out before it was chambered, a spring-loaded plunger was inset near the breech to keep the cartridge in place. Early in the series Connors added a nut to secure the trigger-tripping screw so that it would not accidentally back out.

Connors cranks off 12 shots in slightly less than six seconds during the show’s opening sequence. This mesmerizing feat was made even more miraculous by the fact that the Winchester 1892 carbine only holds 10 rounds. But then, this was Hollywood, where anything is possible.

Some have postulated that because Connors is firing 5-in-1 blanks, which measure 1.3 inches compared to the 1.6-inch length of a loaded .44-40 with a 200-grain bullet, two extra blank cartridges could conceivably fit into the extra space left in the magazine. There is some credence to this, as Connors is seen working the lever 12 times, not 10. (Adding to the intrigue of how many shots Connors fires, there are actually 13 audible shots, a feat made possible by sound dubbing.)

Regardless, this brings up the question of not only how fast but how effective would The Rifleman’s carbine have been in an Old West gunfight if someone actually had that tricked-out Winchester.

Chuck’s exceedingly long reach—he was 6 foot 5—easily cleared the carbine’s 20-inch barrel for his spin cocking routine, but at 5 feet 10 ½ inches, I would ram the muzzle into my shoulder whenever trying to perform this stunt.

After Chuck’s death, I purchased one of his carbines, so I was in a unique position to find out just how practical “The Rifleman’s” rifle would have been in an actual rapid-fire western gunfighter-type shootout, using live ammunition rather than 5-in-1 blanks and firing at a man-size silhouette target at seven yards, which I considered to be a realistic Old West gunfighting distance. Rather than use low-velocity cowboy loads, which wouldn’t have existed in the 1880s, I stoked the carbine with 10 rounds of factory Remington High-Velocity 200-grain ammo.

First, I double-checked the zero with five rounds of slow-fire offhand. Then, satisfied with the point of impact, I moved to rapid-fire. Holding the stock next to my side with my right arm, as Chuck had done in his opening sequence, I pointed the carbine at the target and cranked off 10 shots as fast as I could from hip level (for safety concerns, I did not walk towards the target while firing, as Chuck had done). Needless to say, my 10-shot sequence was not nearly as fast as Chuck’s, as he had reflexes much better than mine and besides, I had to contend with recoil from the live ammo. Still, firing as fast as I could, I managed to empty the magazine in approximately 11 seconds, pointing the carbine at the target rather than taking the time to aim for each shot.

Out of the 10 shots I fired, four hit in the right shoulder era, one hit in the upper shoulder area, two hit close together in the upper torso, two hit in the mid-center chest area and one shot was a complete miss, not striking the target at all. All my hits generally veered to my left, which I attribute to the way I was holding the carbine during this rapid-fire exercise. But the end result was that five of my shots would have clearly disabled my opponent, while the other four would have completely taken him out of the game altogether.

So yes, even though The Rifleman’s rifle didn’t exist in the real west, if it had, it would have been a formidable weapon. I only hope, had this been an actual gunfight, that my complete miss would not have been my first shot!

One reply on “Loop-Lever Rifle Shootout: History of The Rifleman’s Carbine”

That large loop i believe was pioneered by Yakima Canut. I have a 94ae that has the big loop. Never tried hip shooting that 30/30.