Month: October 2024

Bonaparte’s quelling of the Paris mob with cannon fire

Old Nappy was not noted to be a man to be crossed

Martini Henry firing

The AC-130 gunship is one of the most unusual — and feared — special operations aircraft employed by the U.S. Air Force. It is a close air support aircraft designed to loiter over a battlefield and offer ground forces an amazing amount of firepower. In addition to force protection duties, the planes can provide air interdiction — hitting the enemy at night using its advanced reconnaissance technologies to first find and then rain fire on the enemy. In this article, Dr. Will Dabbs tells us what the AC-130 gunships are and how they’ve been used by U.S. forces in Grenada, during Operation Desert Storm and more.

Afriend was an infantry officer during Operation Just Cause, the 1989 invasion of Panama. He told me this story as gospel. He claimed that his unit was tasked to move along a certain road to secure a certain objective. Along the way, they encountered a Panamanian unit tasked to secure the road against any American advance. There resulted a timeless quandary. An unstoppable force was arrayed against an immovable object. Both elements consisted of tooled-up young men with weapons. The foundation was laid for something truly horrible.

Not wishing to precipitate unnecessary bloodshed, the American commander retrieved a Spanish-speaking troop to act as an interpreter. He called a confab with his opposite number and explained his predicament. His Panamanian counterpart felt disinclined to move. By now, it was getting dark. The American CO spoke into his radio and directed the Panamanian officer’s attention toward an empty barn in a distant field.

Counting down from five, the barn exploded in a massive flash just as he reached zero as though touched by the very finger of the Almighty. The Panamanian officer purportedly dismantled his roadblock. This tidy little battle had just been won by a single 105mm howitzer round fired from an unseen AC-130 gunship orbiting in the darkness above.

The Plane

The AC-130 project began in 1967 as a replacement for the AC-47 Spooky gunship. The AC-47 was called Project Gunship I. The subsequent AC-130 was something altogether new and remarkable.

The first AC-130 was converted from a standard A-model Hercules and carried four M61 Vulcan six-barrel 20mm rotary cannon alongside another four GAU-2/A 7.62x51mm miniguns. Aerial gunnery is the very embodiment of physics. An RAF exchange officer named Tom Pinkerton scratchbuilt the first analog fire control computer used by the AC-130 while working at the USAF Avionics Laboratory at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

During operational testing in the Vietnam War, it was determined that the miniguns lacked the necessary range to optimize the platform, so they were deleted. This space was filled with a pair of 40mm L/60 Bofors cannons. I’ve been told that the most precise weapon on those early variants was the 40mm autocannon. In the early 1970s, these aircraft were fitted with a 105mm M102 howitzer near the aft ramp.

The latest versions of the AC-130 carry a single 25mm rotary cannon, a single L/60 Bofors 40mm, and the M102 105mm howitzer. AC-130s in current service can also deploy AGM-176 Griffin missiles, AGM-114 Hellfires, GBU-39 Small Diameter Bombs, or GBU-44/B Viper Strike munitions along with drones and other classified ordnance. While the weapons are always the sexiest part of the equation, what really makes the aircraft such a dominating force on the modern battlefield is its unparalleled sensor suite.

The aircraft has always carried low-light TV and infrared sensors. These advanced avionics have been steadily upgraded since the introduction of the platform. Even back during the Vietnam War, the AC-130 could detect an unshielded ignition coil in a truck from a typical engagement altitude of 7,000 feet. Nowadays, the aircraft carries the AN/APQ-180 multimode attack radar similar to that used on the F-15E Strike Eagle along with a state-of-the-art Raytheon FLIR (Forward-Looking Infrared) and a Lockheed Martin AN/AAQ-39 Gunship Multispectral Sensor System.

The AN/AAQ-39 can see most anything anywhere day or night and includes a variety of laser range finders and automatic target designators. Modern American combat uniforms and helmets typically include a small bit of reflective material on the top to make friendly troops stand out to the AC-130’s sensors at night.

The weapons on the AC-130 are mounted on the port side of the aircraft and are fired by the pilot. By flying pylon turns, a skilled pilot can maintain a steady stream of fire on a point target for as long as the fuel and ammunition holds out. As modern variants are capable of air-to-air refueling, their missions are typically limited solely by the availability of darkness and ammo. I literally cannot imagine how horrible it would be to find oneself on the receiving end of one of these angry birds.

Operational History

These gunships have been employed in every major military engagement in which the United States has been involved from Vietnam to the present day. None have been exported. We are their sole operators.

Six AC-130s were brought down during the Vietnam War by hostile action. Two were lost to surface-to-air missiles, while the remainder fell to anti-aircraft artillery. One AC-130 was shot down by a MANPADS (Man-Portable Air Defense Systems) shoulder-fired missile in 1991 and crashed off the coast of Kuwait. This aircraft, callsign Spirit 03, was lost when its crew made a conscious decision to remain in action in daylight because the Marines they were supporting desperately needed them.

An eighth one was brought down 200 meters off the coast of Kenya while supporting combat operations in Somalia. This last aircraft suffered an in-bore detonation of a 105mm round that severely damaged the left wing. Eight of the fourteen crewmembers aboard survived the crash.

A Most Satisfying Mission

I have a buddy here in town who flew AC-130s operationally. One afternoon after church I asked him to relate his most remarkable combat experience in the plane. Without hesitation, he said it was one particular mission wherein he fired nary a shot. I bid him to proceed.

He was tasked to support a small five-man Special Forces team that had been compromised by the Taliban while on a recon mission in Afghanistan. These poor guys had been awake and on the run for several days. They were just about spent.

While the AC-130 is an undeniably fearsome weapon platform, it is also quite vulnerable. The aircraft is not terribly useful in contested airspace. Its relatively slow speed and long loiter times are benefits against targets bereft of air assets, but these attributes become liabilities in a battlespace liberally populated with MiGs and S-300 air defense systems. In Afghanistan, where the primary anti-aircraft threat was MANPADS, that just meant they flew only at night.

My buddy found the team easily enough and could tell from their first transmission that these guys were at the end of their rope. He took a long slow orbit around the area to ensure there were no bad guys in close proximity and then simply told the team leader to shut down and get some rest. There was no need to put out security. He would take care of that.

The Green Berets bedded down for some well-deserved shuteye, while my pal simply flew circles in the night keeping an eye out until he hit bingo fuel. At the end of the evening the SF guys were well-rested and my buddy returned to base with a full load of ordnance. Nobody got killed, and the special operators got a good night’s sleep.

This is not just a 1911 story. It is a treasure story, just as much a mystery, and there is definitely magic involved. The story involves a multi-generational saga, so it defies normal categorization. But that is what makes it worth telling.

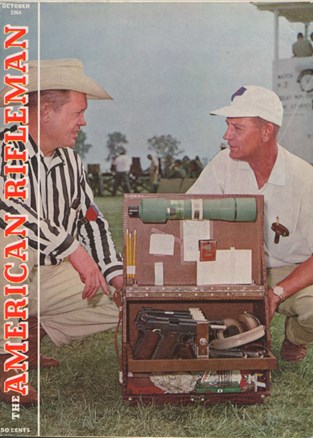

Like every good tale, this one begins with a “So there I was” … surfing Gunbroker looking at a few reliable sellers who have great stuff. I needed nothing and was simply enjoying some browsing. And then, there it was. The title said “Colt 1911… Arsenal rebuilt, 1913 US Property frame.” The images showed a well-used 1911 set up as a National Match or bullseye “hardball” gun.

The slide and frame were made by Colt, but the slide had later commercial roll marks, while the frame was an original 1911-style without the trigger scallops. The “UNITED STATES PROPERTY” stamp and the inspector’s cartouche proved its G.I. heritage, while the 31,000’s serial number put it at 1913, a little more than a year from Colt’s initial deliveries of the pistol.

The frame was stippled with a punch rather haphazardly, and the arched mainspring housing had been worked over diagonally and deeply with some sort of file for a coarse, “checkered” effect. The slide wore a National Match front sight matched up to an old-style Colt Eliason adjustable rear.

The long aluminum trigger had unsightly divots where there was once a trigger shoe installed, and someone had scrawled “BAB” in electro-pencil on the inboard side. The slide had “1332” marked under the ejection port, worn faint from some polishing that had occurred before the mismatched upper and lower had been re-blued together.

Everything about this pistol was slightly off. You wouldn’t expect to find such an early frame mated to what appeared to be a National Match slide. However, something about this pistol absolutely shouted “military armorer build” to me.

Everything about this pistol was slightly off. You wouldn’t expect to find such an early frame mated to what appeared to be a National Match slide. However, something about this pistol absolutely shouted “military armorer build” to me.

When I shot for one of the Marine Corps’ station pistol teams we had been issued old Quantico-built National Match-style .45s, and this had that look—a number of small tells that appeared emblematic of a military build. Military armorers tend to be oblivious to cosmetic touches, for example, and tend to stipple in a way that no commercial pistol-smith would—functional; effective; ugly.

Bidding on a mixmaster match gun is high risk; the lockwork is almost certainly messed with—perhaps poorly—the two halves may not function reliably as a whole, etc. I barely stopped to consider these or other pitfalls, though I’ve been burned on auction sites before. Something about the photos of this Colt spoke to me in a way that no other pistol ever has. It was as if this .45 was reaching out to me through the internet.

Not in a puppy at the pound, please take me home way. More like excalibur in the stone beckoning Arthur to come release it. I named my price. Apparently the rest of the internet simply saw a mixmaster, beater 1911. A complete 1913 manufacture Army Colt would be a hefty sum. Likewise would be a complete postwar National Match. My winning bid was a couple hundred dollars less than the rack-grade price of current CMP mixed-part 1911A1s.

When the Colt arrived it took only one cycling of the action to confirm my hopes. The pistol cycled like the very best custom 1911s from an earlier era. It was tightly fitted in a way that in the days of pre-CNC machined and custom-mated parts meant hours of careful work. The pistol was almost perfectly tight, but cycled with an oily smoothness that inspired admiration and confidence. I had every suspicion this was going to be a shooter.

When the Colt arrived it took only one cycling of the action to confirm my hopes. The pistol cycled like the very best custom 1911s from an earlier era. It was tightly fitted in a way that in the days of pre-CNC machined and custom-mated parts meant hours of careful work. The pistol was almost perfectly tight, but cycled with an oily smoothness that inspired admiration and confidence. I had every suspicion this was going to be a shooter.

The custom Colt felt really good in the hand, the ugly-duckling stippling and checkering almost perfectly coarse for my taste, and the aged figured walnut stocks with plenty of bite left on the checkered points. I verified empty and tested the trigger pull. I’ve had the great fortune to handle a large number of custom, semi-custom and just plain nice pistols, and the first press on a great trigger never gets old. This one brought a deep smile to my face. If I said it was like perfection dipped in warm chocolate, it is probably a better description than the usual 1911 cliches. I was wiling to bet money the trigger was breaking a feather above 4 lbs. (the rulebook minimum for a service pistol). Upon measurement … 4.09 lbs. This with old school parts—the early long trigger, a G.I. hammer that had been milled down to reduce hammer bite and weight and likely a G.I. sear and spring.

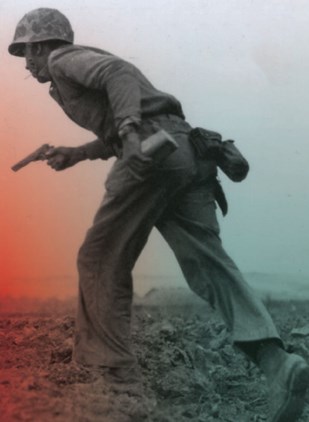

I thought about the old 1913 frame on the gun. This thing was made just as Theodore Roosevelt had lost his Bull Moose party run for the presidency and Woodrow Wilson took office. The Colt had probably gone to the border in a cavalry flap holster, either on horseback or in one of the “new” motor cars to chase Pancho Villa. You can almost imagine the wonderment of the trooper as he handled the cutting edge, “self-loading” .45. The Colt almost certainly went “Over There” with the same soldier, or perhaps another doughboy to fight through the trenches in World War I. The “AA” marking on the dust cover showed the pistol was overhauled at the Augusta Arsenal for further service, and very likely served through the Second World War with another generation. I could picture this same pistol comforting some G.I. through long nights on some steamy Pacific island, ready to repel a banzai charge or clenched in hand to clear caves and tunnels.

I thought about the old 1913 frame on the gun. This thing was made just as Theodore Roosevelt had lost his Bull Moose party run for the presidency and Woodrow Wilson took office. The Colt had probably gone to the border in a cavalry flap holster, either on horseback or in one of the “new” motor cars to chase Pancho Villa. You can almost imagine the wonderment of the trooper as he handled the cutting edge, “self-loading” .45. The Colt almost certainly went “Over There” with the same soldier, or perhaps another doughboy to fight through the trenches in World War I. The “AA” marking on the dust cover showed the pistol was overhauled at the Augusta Arsenal for further service, and very likely served through the Second World War with another generation. I could picture this same pistol comforting some G.I. through long nights on some steamy Pacific island, ready to repel a banzai charge or clenched in hand to clear caves and tunnels.

How did this thing end up with a National Match slide? I had a couple of working theories. In one, a talented armorer chose the 1913 frame because of its fit on the slide, and as it was older, it wouldn’t be a loss to dedicate it as a match gun. In another—less charitable—an armorer brought home some parts, including the NM serialized slide, and built them up on a cheap, recently DCM (precursor to CMP) surplus, arsenal-rebuilt, 1911 frame. Whoever the smith and whatever the path that brought these two Colt halves together, it is a happy ending.

And who was the “BAB” represented by the letters on the trigger? The ‘smith, or perhaps the shooter? The parts and build of this pistol suggest a late 1950s or early 1960s timeframe, smack dab in the golden age of bullseye shooting as the predominant pistol sport. Did the original owner proudly heft this Colt and stack enough “X”s to win a shelf of trophies? I tend to believe so, though with no way of substantiating it.

And who was the “BAB” represented by the letters on the trigger? The ‘smith, or perhaps the shooter? The parts and build of this pistol suggest a late 1950s or early 1960s timeframe, smack dab in the golden age of bullseye shooting as the predominant pistol sport. Did the original owner proudly heft this Colt and stack enough “X”s to win a shelf of trophies? I tend to believe so, though with no way of substantiating it.

I took the old Colt to the range and starting shooting. It cycled smoothly and reliably, with the oily grace only a full custom build produces. When shooting an old loose 1911, the parts are rattling together into a locked position, then every motion in the firing cycle imparts a subtle jolt as the parts jostle back and forth. When the design is fitted tight and right there is a smoothness that is a wholly different experience (most current-production 1911s are thankfully past the midpoint on this spectrum). One might compare it to the difference between cutting a fine steak with a coarse serrated knife and a razor-sharp steak knife. Both produce the same function with a similar motion, but the feel is entirely dissimilar.

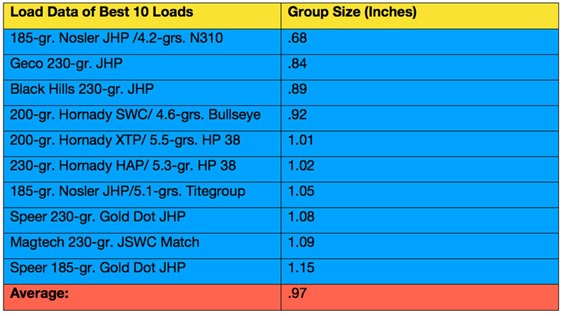

I fired a few representative groups with different loads. Some Black Hills hollow points punched into less than an inch, some MagTech semi-wadcutters just barely over. A couple of handloads piled three or four into a single hole with a fifth close by. I was as excited as a kid catching his first fish. This kicked off the quest.

For months I would bring the National Match out on each range trip and log a few more loads. I would mostly fire one representative group, maybe a second or third group if there was real potential, or if I felt there were some fliers. After the first six or so, the average was about an inch and a quarter—a group that would neatly nearly fit under the inch and a half cap to the typical gallon jug of milk. At 10 groups the average hadn’t budged, nor at 15. By 20, the average had started to creep closer to an inch. I found loads with multiple bullet styles and weights, and several powders that would cut ragged holes. The Colt was indifferent to whether the loads were hardball, modern defensive hollow points or match loads- every shot seemed to pull the next one close.

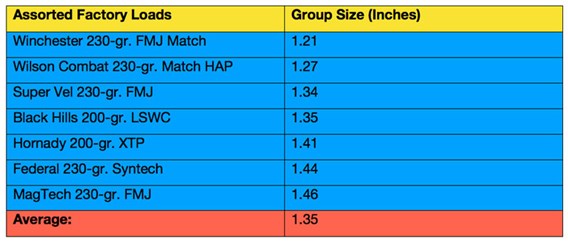

As of this writing, the best 10 loads average under an inch at .97”. The average of over 25 different loads is 1.18”. Some highlights are in the table, but this is perhaps the most consistently accurate 1911 I’ve fired. Keep in mind, these groups are all fired over a standing rest—my preferred method—but also one that makes groups much under an inch and a quarter a real challenge.

Outside of the 25-yd. groups I have pushed the old Colt on some challenging drills with results beyond what I can guarantee with even current custom pistols. In a nutshell, this 107-year-old Colt has 40 ozs. of magic forged into its Hartford steel.

I often shoot the plate rack at 50 yards for a challenge. With some pistols, that is better described as “I hit some plates at 50 yards,” and with others, it is “I hit most plates at 50 yards.” The mixed Colt shrugged off the plates like they were a gimme, so I began actually running the rack of six for time. My current best center-fire semi-automatic time belongs to the Colt, with a time so short it challenges belief.

Here is a fun fact: Most .45 ACP loads when sighted for a 6 o’clock hold at 25 yards will strike close to dead on at 70. With the old Colt, I started lobbing rounds at the 8” plates from 70 yards on most trips. I was able to record eight or nine hits out of 10 with numerous loads. On several days where the light was ideal and I was shooting strongly, most of those impacts formed nearly overlapping spatter marks into a fist-sized group. At present, my best is 10 out of 11, and hopefully by the time this is printed, I’ll have a perfect run.

Shooting this National Match is a unique and distinctly rewarding experience. Every time I marvel at how well it shoots from a purely practical point of view. This invariably leads to a deep appreciation for the pistolsmith who fitted it up and tuned it so expertly some 60 or more years ago. That leads as often as not to wondering about the past lives that have intertwined with a common bond in this old Colt over the last century-plus in service, combat and competition. It is no surprise that wrapping a hand around that frame is akin to shaking hands with something special. I’m just glad that the old Colt found me.

Herter’s revolver with 6″ barrel and Mike’s “custom” purple heart grips. He found it to be a fun shooter, but confesses he’s no gripmaker!

As Mike says, if you squint a bit it doesn’t look too bad in spite of the “original” grips on it when he bought it.

Readers in my age group likely remember when the Herter’s Company had a thriving mail order sporting goods business, selling everything from firearms and ammunition, reloading equipment and fishing tackle to camping supplies. This was in a different America, one that must still give Hillary Clinton and her ilk nightmares. In “those days” customers could order a firearm — even a handgun — through the mail and have it delivered to their doorstep, and with no paperwork or permits involved.

Herter’s revolvers were based on the Colt single action — as were most other SA revolvers of the time — and priced lower than a Ruger or Colt. Lest we assume they were strictly a “cheap” gun, they were imported by Herter’s, but produced in Western Germany by J.P. Sauer & Sohn. These revolvers were solidly constructed, with good sights, had case head recesses in the cylinders and were produced in .357 Magnum, .44 Magnum and a cartridge exclusive to Herter’s, the .401 Herter’s Powermag.

Way back in the early 1970’s, I swapped for a .44 Magnum Herter’s, the first .44 Mag. I ever owned, or shot. Mine had a 4″ barrel, which I now understand was a rare edition, and the recoil was stout, to put it mildly. After every cylinder of ammo fired I had to tighten all the action screws. And the cylinder base pin was prone to jump out fairly often. Still, I got a real kick out of sliding those big .44 cartridges into the chambers and holding on tight when it fired!

I finally sold it after losing the base pin in the woods, but had fond enough memories of it to make a swap recently for another .44 Mag. Herter’s. My “new” Herter’s revolver is in slightly better shape than the first one, although it needed a very thorough cleaning to be smoothly operational. This one has a 6″ barrel, and I have had enough experience with big bore revolvers by now that recoil is not as intimidating as on that first .44 Magnum.

The appearance of this gun was a bit sad, however, even for a handgun made in 1966. The grips appeared to have been carved from pine plywood with a dull pocketknife and the finish was a bit worn. I first made a set of grips from a piece of white oak once part of the engine bed in a friend’s old wooden 39-foot Post sportfishing boat.

Then I stripped the worn bluing off. The grip frame, cylinder, barrel and ejector rod housing have been so far left as polished steel, but the cylinder frame was “rust browned,” mostly because I wanted to see what it would look like. Finding the resulting finish was to my liking, and was also sometimes referred to as “plum brown,” I fashioned a set of grips from purple heart wood. This resulted in the revolver being given the nickname “Deep Purple.” I am by no means a competent grip-maker, but I like the way these turned out, especially after I decided to use magnets to hold them to the heavy steel grip frame. There’s no screw heads or nuts showing.

A criticism of the Herter’s guns was they were not attractive. But — in all modesty — I think my .44 is!

The .44 Magnum (top) and .401 below. Mike found them both to

be fun, shootable and rugged for the money. They were made in

Germany by J.P. Sauer & Sohn. Thanks to Mr. & Mrs. Leroy Anderle

(Mike’s in-laws) for the use of their garden rock for the photo.

Very Affordable

The Herter’s revolvers are actually beginning to have some collector interest, but prices are still very low compared to a Ruger or Colt. The main value of these guns, though, is probably as shooters. I would expect mine to withstand “heavy” .44 Mag. loads easily, but I have settled on handloads using .44 Mag. brass and .44 Special power levels pushing 290-grain cast bullets of which I have a large supply. With a modest charge of Titegroup I get a bit over 800 fps, which will allow the old gun to complete its long life cycle as a “woods walking” gun for me to use on feral hogs.

The reason for the longer .44 Mag. brass is because I spent some time with a wire brush on a drill “polishing” out the carbon rings in the cylinders left by a previous owner shooting a bunch of the shorter .44 Special ammo. I actually load all my .44 Mag. ammo for my Rugers and Contenders to 1,000 fps or less with heavy-for-caliber, hard-cast bullets. These get the job done even on large hogs and are much more pleasant to shoot.

I found myself enjoying the refurbishing of this revolver so much I began a search for another Herter’s to work on, since I will not be doing a lot of things to my Rugers. After one obvious approach by a scammer, my WTB ad produced a contact from a gentleman in Sante Fe, Texas, about 30 miles down the road from my home. Turns out he collects Herter’s guns. He told me he had a .357 Mag., a .44 Mag. and four of the much harder to find .401 Powermag revolvers.

He now only has three .401’s! The .401 has an actual bore of usually around 0.403″ and is often surmised to have been the inspiration for the .41 Remington Magnum, which came later in handgun history. Early .401’s were stamped as “Single Six” on the barrel, but Ruger objected to this, since they had a prior claim to the name, so most still in the factory had those letters stamped through with “X’s.” My new friend has one of those with the Single Six lettering not stamped out.

Original Herter’s .401 Powermag ammo is scarce

as hen’s teeth. Here’s an original box.

.401 Ammo

The original ammo sold by Herter’s used cases made by Norma, and has not been offered for many years. Boxes of the original ammo can be found on gun auction sites, or eBay, for very premium prices. New loading dies for .401 Powermag are available from Buffalo Arms, but 10mm dies can be used for most of the process. I soon found GAD Custom Cartridge, of Medford, Wis., offers .401 ammo loaded in used original cases as well as in “formed” cases made from .41 Mag brass. I also found out .30-30 brass can also be used to make .401 brass.

Missouri Bullet Company made up a “sample pack” for me of their “Hi-Tek” coated hard cast 180-grain TCFP bullets with a Brinell Hardness Number of 18. The bullet has an un-sized diameter of 0.402″, which measures 0.403″ with the coating. These are working very well in my revolver.

Although built on the same frame, there are some differences between the .44 Mag. and the .401, other than cylinder size. The most obvious is the trigger pull. My .44 Mag. version shows 4 lbs. of pull to break on my gauge, but the .401 is almost scary, breaking at less than 2 lbs.! David Reis, from whom I obtained my .401, says all of his had a similar trigger, so it apparently left the factory that way. This will take some getting used to for me, as I am not normally a light trigger advocate (but I’m thinking I may end up liking it!).

The sights on both Herter’s versions are good, with a tall ramp front Elmer Keith would have loved, and an adjustable rear. While the rear sight on the .401 is of a “normal” notch variety, my .44 Mag. has a gold rear leaf of the semi-buckhorn style probably added at some point in its history.

Herter’s grip frames are much larger than those of a Ruger Super Blackhawk — the reason I had to make new grips — and have a Bisley-like shape. The action shows the familiar 3 screws of an Old Model Ruger, and the guns have the half-cock loading position of older Rugers and Colts. Since I’ve been looking for an Old Model Ruger at a decent price, I was happy to find this action on the Herter’s.

The .44 Mag. proved to have decent accuracy at 25 yards, and seemed to do better with the hotter loads I tried.

The original .401 models had “Single Six” on the barrels but were

stamped out at the factory due to a conflict with Ruger’s

Single Six model name.

Challenges

The drawback to a .401 as a shooter of course, would be the lack of ammunition. David Reis has a good accumulation of both brass and loaded ammo, but is saving them for his grandchildren to enjoy.

In correspondence with Lee Martin of Singleactions.com, who has several Herter’s revolvers in his collection — including .401’s — I was made aware it’s possible to rechamber a Herter’s .357 Mag cylinder to 10mm, making a .401 into a convertible! The cost of such a procedure will be much less than a Ruger “Buckeye Special” with .38-40 and 10mm cylinders, and even those are getting hard to find!

I have a .357 cylinder I got from Numrich I will be taking to Allan Harton soon for this surgery. David Reis is an officer in the Cast Bullet Association and reminded me 10mm bullets will be a bit small for the 0.403″ bore in the Herter’s. However, since he has every mold produced for the .401, we are confident we can get cast bullets to perform well in this application.

Lee also told me a .401 cylinder can be rechambered to .38-40, adding a third chambering to the switch-cylinder capability, and Numrich also lists these as being in stock. Since the .38-40 can be loaded to some impressive velocities with modern powders, this might be an attractive option as well.

So, the old Herter’s revolvers are getting harder to find. But, they are still available at reasonable prices, very shootable in most cases and offer both a glimpse back into handgunning history and one of the few chances to own a 10mm revolver. They are heavy, well-built firearms, and with a little “re-modeling” work — and if you squint your eyes just right — they aren’t half-bad looking!