Month: May 2024

Its even worse than I thought

Erik Prince on the many failures of the U.S. military.

(6:40) Erik Prince on The Liz Cheney Wing of Congress

(32:45) The Main Villains of The Iraq and Afghanistan Wars

(40:48) Where does the Money We Send to Ukraine Really Go?

(1:21:34) Why are the Climate Change Zombies… pic.twitter.com/WT9NsQWY9g— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) May 21, 2024

SIG P365

When the British Empire adopted the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-musket, the design became one of the more significant military small arms of the mid-19th century. This was largely due to the fact that it was one of the first broadly produced muzzle-loading percussion rifles made. The industrial capacity and worldwide empire of Great Britain at the time also meant that large numbers of them were used around the world.

Yet, when the British infantry adopted the Pattern 1853, it meant that the British cavalry needed their own version as well. Prior to this point, the British cavalry were using the Pattern 1851 Victoria Percussion Carbine which had a large bore and reportedly strong recoil due to the size. Three years after the adoption of the Pattern 1853, British cavalry finally received their own shortened version, the Pattern 1856 Cavalry Carbine.

The Pattern 1856 Cavalry Carbine is a percussion-fired, muzzle-loaded short rifle musket with a .577-cal. bore. It was much shorter and lighter than the fullsize Pattern 1853, with the latter sporting a 39″ barrel while the carbine has a 21″ barrel. The Pattern 1856 also has two bands connecting the barrel to the wood fore-end instead of three as found on the fullsize Pattern 1853. The lock design was essentially unchanged between the Pattern 1853 and Pattern 1856.

Being a carbine intended for use on horseback, the Pattern 1856 features a saddle rig and carrying bar attached to the left side opposite of the lock. One of the most interesting and utilitarian features on the Pattern 1856 is the captive ramrod. A swivel attached to the ramrod allows the ramrod to be pulled out of the fore-end and positioned over the muzzle to load, but does not allow the ramrod to fall free of the carbine. This is a handy feature for a muzzle-loading carbine intended for use on horseback where it would otherwise be easy to lose the ramrod.

The Pattern 1856 also features a front sight in the form of a subdued blade and a rear sight with adjustable folding leaves for different set ranges. The Pattern 1856 Cavalry Carbine was adopted at a time when the British were beginning to consider transitioning to cartridge and breech-loading arms, and thus did not end up having a very long service life in the British Army. It was also produced in fewer numbers than the fullsize Pattern 1853 rifle musket, given its niche role as a cavalry carbine.

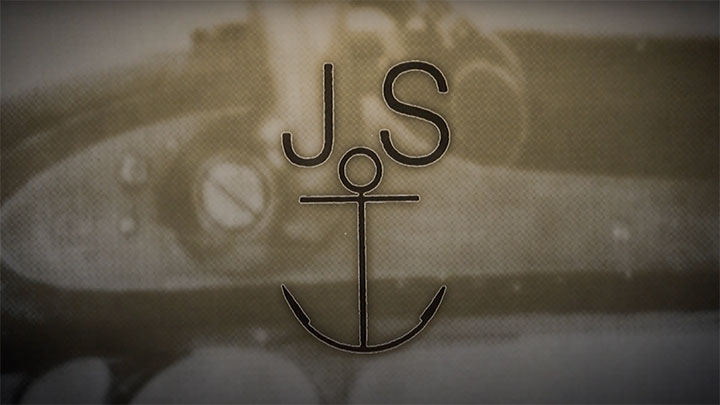

Despite this, The Pattern 1856 did catch the attention of purchasing agents in the rebelling Confederate states in America, who purchased more than thousand of them for import between 1861 and 1865. Confederate blockade runners brought the carbines to the Confederacy all the way into the last year of the war. These imported Pattern 1856 carbines for Confederate use are typically have a Birmingham Small Arms trade stamp on the stock, as well as a “J”, “S” and anchor stamping.

Actual Confederate-use Pattern 1856 Cavalry Carbines are fairly scarce in the U.S. collecting market today, with a large number of fakes being possible as is the case with many Civil War collectables. One explanation for the shortage of these Pattern 1856 carbines stems from a report from the 7th Indiana Cavalry. On Dec. 28, 1864, the 7th Indiana Cavalry surprised and overran a Confederate dismounted cavalry camp in Miss. and destroyed their stores in the process, which included 4,000 carbines.

To watch complete segments of past episodes of American Rifleman TV, go to americanrifleman.org/artv. For all-new episodes of ARTV, tune in Wednesday nights to Outdoor Channel 8:30 p.m. and 11:30 p.m. EST.