Month: May 2024

Introduced more than a century ago, the basic design of the Smith & Wesson hand ejector continues to define double-action pistols today.

What You Need To Know About Smith & Wesson Hand Ejector Revolvers:

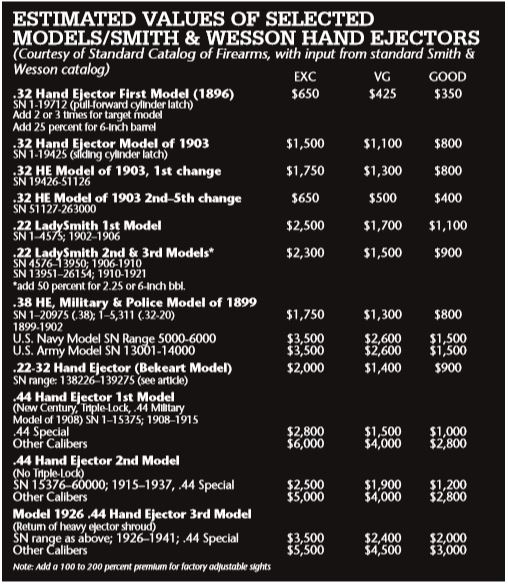

- The first hand ejector model was the .32 Hand Ejector Model of 1896.

- Soon to follow was S&W’s first K-frame revolver—the .38 Military Model 1899 or .38 Hand Ejector Military & Police.

- The first Triple-Lock was .44 Hand Ejector First Model (New Century, Triple-Lock, .44 Military Model of 1908).

- For many, this hand-ejector model is considered to be the finest double-action pistol ever made.

Among the many contributions Smith & Wesson has given to the firearms industry, the most significant would have to be the Hand Ejector revolver. This series of solid-frame, double-action models with swing-out cylinders and manual case extraction has certainly stood the test of time. Introduced in 1896, its basic design is still in production, not only by Smith & Wesson, but also by many other gun manufacturers around the world. Author Jim Supica wrote in Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, “The Hand Ejector is the style of handgun that epitomizes Smith & Wesson.”

The focus of this column is on Hand Ejector models of the pre-World War II years with “Hand Ejector” in their official names. When referring to the basic design, all Smith & Wesson revolvers made since 1899 can be described as “hand ejectors,” but my plan here is to provide a bit of history on the original named models.

Toward the end of the 19th century, Smith & Wesson began work on a new-style revolver—one with a solid frame that would soon replace the popular top-break models the company had been known for since the 1870s. “Hand Ejector” is a reference to the loading and unloading procedure, whereby the shooter releases the cylinder to tilt out of the left side of the gun. This allows the cylinder to be loaded or for the fired cases to be “hand-ejected” by pushing back on the ejector rod.

Background: The .32 Hand Ejector

The first revolver to be given the name was the .32 Hand Ejector Model of 1896, its year of introduction. It was made on a new frame size called the I-frame, which had been designed for a new cartridge, the .32 S&W Long. Smith & Wesson lengthened the case of the .32 S&W by 1/8 inch to increase its powder capacity, and this required a slightly larger frame.

The Model of 1896—which would later be known as the .32 Hand Ejector First Model—was made for only seven years. It was not a big success on the civilian market, but a few major police departments, including Philadelphia’s, adopted the model as a service revolver.1

In 1903, the Second Model was introduced, along with several design improvements. The .32 Hand Ejector Model of 1903 remained in production until 1917, with a series of five changes over that time period.2 These differences were relatively minor for the first four model changes, with somewhat more significant variations internally with the fifth change.

The K-Frame Revolver

Another major contribution to firearms history from Smith & Wesson occurred in 1899 with the introduction of the first K-frame revolver—the .38 Military Model 1899 or .38 Hand Ejector Military & Police. K-frame models are still being made and are now well into their second century. They remain very popular; more K-frames have been manufactured than all other Smith & Wesson revolvers combined.3

At the same time the .38 Hand Ejector of 1899 was introduced, the most popular revolver cartridge of the 20th century, the .38 Special—or, to be precise, the .38 S&W Special—was introduced. Two of the most popular variants of this model with collectors are the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy models. These are marked “U.S. Army/Model 1899” or “U.S.N.” One thousand of each were made in 1900 and 1901.

The .32-20 was a popular cartridge in the late-19th and early-20th centuries and was another .32-caliber Hand Ejector. It went through six changes as the .32 Hand Ejector Model of 1902 and then, the Model of 1905.

The last variant remained in production until 1940. It was also made on the K-frame and could be considered the predecessor of one of the rarest Smith & Wesson models: the K-32 Hand Ejector First Model (K-32 Target). Chambered for the .32 S&W Long, only about 94 were made throughout the 1936–1941 period leading up to the beginning of World War II. Its rarity makes this version of the K-32 one of the priciest S&W collectibles.

The .22s

Several of the early Hand Ejectors were .22s. The first of these was the .22 Hand Ejector (LadySmith). Made on the tiny M-frame, it had a seven-shot cylinder and was chambered for the .22 S&W cartridge (which was the same as the .22 Long). It was in production from 1902 through 1921, with three model changes and serial number ranges.

Smith & Wesson resurrected the name, written “LadySmith,” in 1990 for a 9mm semi-auto and later for a J-frame .38 Special, which is still in the catalog.

The Bekeart Model

The .22-32 Hand Ejector had an interesting beginning. A San Francisco gun dealer named Philip Bekeart came up with the idea for Smith & Wesson to build on the .32 Hand Ejector I-frame a .22-caliber model with a 6-inch barrel and adjustable sights. He believed in the concept so much that he placed a special order in 1911 for 1,000 of these revolvers. These guns became known as Bekeart models and are highly collectible. Only 292 of the first 1,000 guns were delivered to Bekeart, and some went to other dealers. It was 1915 before Smith & Wesson put the model into regular production.

Bekeart models were not marked, so identifying them can be confusing. Serial numbers were included in the range of those for the .32 Hand Ejector (from 138226–139275), but there was a special and separate series of serial numbers stamped on the buttstock of the first 3,000, beginning with the letter “I.”4 Some collectors consider any .22-32 Hand Ejector with a letter showing shipment to Bekeart’s gun shop to be a Bekeart model. This revolver remained in production until 1941.

The N Size

The largest frame for Smith & Wesson revolvers for nearly 100 years was the N size. It was designed for a new cartridge, the .44 Special, and came aboard the S&W train in 1908. Based on a lengthened .44 Russian case, the .44 S&W Special could hold three more grains of black powder under a round-nosed, 246-grain lead bullet.5 (Some .44 Special fans might disagree with the statement that the cartridge was originally loaded with black powder, but six-gun guru John Taffin says so in Gun Digest Book of the .44.)

More Gun Collecting Info:

- The Walther PP Series

- The Quintessential 22 Pistol: The Colt Woodsman

- The Rocky History Of The L.C. Smith

- The Browning SA-22

- Colt Python: The Cadillac Of Revolvers

The Triple-Lock

The complete name of this revolver was quite a mouthful: .44 Hand Ejector First Model (New Century, Triple-Lock, .44 Military Model of 1908). Buried in the name is a feature that referred to the lockup of the cylinder; this feature became one of the nicknames of the model: the Triple-Lock. It was also often called the New Century.

In the Gun Digest Book of the .44, Taffin describes it as “the epitome of double-action six-guns: The New Century, alias the .44 Hand Ejector First Model, which would forever be known to its loyal followers as the Triple-Lock … In addition to enlarging the frame, two other improvements were made. A shroud was added to the bottom of the barrel to enclose the ejector rod, thus not only protecting the ejector rod, but also improving the looks of the S&W revolver. The second, unfortunately short-lived, improvement was the addition of a third lock, giving the Triple-Lock its unofficial name. Before, the .44 Hand Ejector First Model S&W cylinders locked only at the rear of the cylinder and at the front of the ejector rod. On the New Century, a third lock was brilliantly machined in the front of the frame at the yoke and barrel junction to solidly lock the cylinder in place.”

Interestingly, the Triple-Lock was in production only seven years. Apparently, in 1915, someone at Smith & Wesson decided that the third lock was too expensive to manufacture, and it was eliminated—as was the shroud around the ejector rod. Following the changes, the price of the revolver was reduced from $21 to $19.

About 15,375 Triple-Locks were made before the changes took place; most, but not all, were .44 Specials. A limited number was chambered in .38-40, .44-40, .445 Colt and .455 Mark II.

The .44 Hand Ejector Second Model—as it was now known—was made from 1915 to 1917, when wartime work called a halt to large-frame revolver production. The model returned to the S&W line in December 1920 and remained there until 1940.

The Third Model

Another popular .44 Hand Ejector model, called the Third Model or the Model of 1926, was added in that year. It was identical to the Second Model except for the return of the ejector rod shroud. Smith & Wesson received a large number of inquiries asking for the heavier barrel lug—many from law enforcement agencies wanting a slightly heavier revolver. The Third Model was a special-order gun until July 1940, when it was listed in the Smith & Wesson catalog shortly before it was discontinued. It was reintroduced in 1946, following the war.6

For more historical and technical information on these great revolvers, the books listed below in the footnotes are excellent sources.

FOOTNOTES

1, 6: History of Smith & Wesson, Roy G. Jinks, Beinfeld Publishing, 1977

2, 4: Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, Jim Supica and Richard Nahas, Gun Digest Books, 2004

3, 5: Gun Digest Book of the .44, John Taffin, 2006

Private First Class Ralph Kollberg, a combat veteran of the U.S. Army’s 77th Infantry Division, poses with his M1919A6 machine gun on Okinawa, May 14, 1945. Despite the gun’s 32-lb., 8-oz., weight, it was far more portable than the tripod-mounted M1919A4.

One of the most popular and effective U.S. small arms of World War II was the M1919A4 light machine gun. Despite the almost universal accolades heaped upon the M1919A4, the U.S. Army Ordnance Dept. continued to seek ways to increase the gun’s utility. While attempting to improve upon existing designs is not a bad thing in and of itself, sometimes the “Law of Unintended Consequences” comes into play.

A good example of this in the realm of World War II U.S. military arms was the Model 1918A2 Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). As a brief review, when the M1918 BAR was fielded late in World War I, it was an immediate sensation and was, hands-down, the best gun of its genre in the world at the time. The Ordnance Dept. couldn’t leave well enough alone, however, and after World War I, the BAR was subsequently fitted with all manner of attachments that were intended to improve it, including bipods, stock rests, folding buttplates, receiver magazine guides and carrying handles. The popular selective-fire feature allowing either full-automatic or semi-automatic operation was discarded on the M1918A2 version and was replaced with a full-automatic-only mechanism consisting of “slow” and “fast” cyclical rates of fire that few of the users liked, or employed, and which was prone to malfunction.

Most of these “improvements” offered few real advantages but seriously mitigated one of the major hallmarks of the original design—its comparatively light weight and handiness. This resulted in many of the users disregarding or stripping off as many of the extraneous features as possible, especially the bipod, in an attempt to put the gun back in the configuration originally designed by John Browning.

A similar scenario occurred during World War II with the M1919A4 machine gun. Since before World War II, the U.S. military had been seeking a gun that could fill the perceived gap between the BAR and the M1919A4. Several designs were evaluated in 1941 and early 1942, but none were deemed to be satisfactory. As the war progressed, there were increased requests for a machine gun of this type. Although the M1919A4 was widely used with notable effectiveness during the war, there were some negative points cited in a 1943 Marine Corps evaluation of the gun:

“Some weapons platoon leaders believe the gun (M1919A4) to be too slow in getting into action and the crew too vulnerable. It is suggested that a new mount for close in jungle fighting be designed, on the order of the bipod and butt-rest similar to the BAR M1918A2 with the addition of a carrying handle on the barrel jacket similar to the British Bren.”

The Ordnance Dept. wanted to develop a new type of gun with the attributes that were being sought and resisted the suggestions to simply field a modified M1919A4 instead. A World War II Ordnance Dept. report stated: “[It] is believed that no advantage would accrue in recommending a modification of the M1919A4 machine gun at this time, as such modifications would meet the approved military characteristics of the light machine gun in part only.”

The Infantry Board did not agree with the Ordnance Dept. assessment and was of the opinion that a modified M1919A4 might not be optimal, but it would fulfill the requirements until a more suitable type of firearm could be developed.

As documented in an Infantry Board report: “The Infantry Board favors a project by the Ordnance Department for the development of a light machine gun. However, based on past experience, the Board believes that the time consumed in the development, technical testing, production of pilot models, service testing, adoption as standard for issue, set up for manufacture and distribution to the services will be so great that under the best of conditions of accelerated procedure, it will be a distant date before the weapon can be placed in the hands of the troops. These modifications for the M1919A4, namely a lighter barrel, no muzzle plug, an 041 spring, a bipod and a shoulder rest … should present no great manufacturing difficulties, and after the items are manufactured, the modifications can be made in the field. If this is accomplished, the services would have a flexible and satisfactory light machine gun at an early date, certainly many months before a new type of light machine gun can be developed and distributed.

“While these modifications [of the M1919A4] do not constitute the ultimate in the development of a light machine gun, they do give a satisfactory gun in a minimum amount of time and manufacturing adjustment.

“The Infantry Board considers the modification of the M1919A4 Machine Gun a matter of major importance to the infantry … and recommends that action be taken to accomplish this modification … .”

This position was very much akin to the hoary old saying, “Perfect is the enemy of the good” or, to paraphrase Gen. George S. Patton, “A good plan now is better than a perfect plan later.” The Infantry Board prevailed, and the modified M1919A4 was recommended for adoption as the “M1919A6.” As stated in the book Machine Guns Of The United States: “The most recent modification of the Model 1919A4, for infantry use, is the Model 1919A6 which incorporates a pressed-metal shoulder stock, a carrying handle, and a bipod similar to that used with the Browning Automatic Rifle. This results in a light machine gun—classed as substitute standard—suitable for air-borne troops as well as for general use. Though the barrel of this gun weighs 2.5 pounds less than that of the 1919A4, the two are interchangeable. This model became substitute standard on April 10, 1943.”

The M1919A6 machine gun was succinctly described by noted author and former Ordnance Dept. officer, the late Konrad F. Schreier, Jr.: “[T]he most unique gun in the M1919 series was the M1919A6. It featured a detachable shoulder stock, a folding bipod on the end of the barrel, a carrying handle, a different barrel bearing than the M1919A4 and a lighter barrel.

Its basic action was identical to the air-cooled M1919A4 machine gun. The gun weighed 32.5 pounds, which made it 12.5 pounds lighter than the M1919A4 mounted on the M2 tripod. A total of 43,479 M1919A6 light machine guns were produced during World War II by Saginaw. However, a number of M1919A4 machine guns were also converted into M1919A6 configuration. The M1919A6 machine guns were manufactured from very late 1943 through 1945. The M1919A6 machine gun could also be used with the M2 tripod if necessary.”

The Ordnance Dept. was not a big fan of the M1919A6, and basically felt that the gun was foisted upon it by the Infantry Board. Paradoxically, while the Infantry Board was successful in lobbying for acceptance of the modified M1919A4, as events transpired, the Board wasn’t overjoyed with the M1919A6 either.

As related by author Dolf Goldsmith: “[T]he Ordnance Department … was most unhappy about their inability to create and supply the infantry with what they had requested … . After the M1919A6 was accepted, testing began anew. Every conceivable facet of the gun was tested … throughout the spring and summer of 1944 … the infantry was … less than happy with the M1919A6, but there was simply nothing else available that could have been used instead. This grudging acceptance is well brought out in one of the test reports, which concluded:

“That the Production Model, Machine Gun, Caliber .30, M1919A6 is substantially equal to the pre-production model as tested and approved, and is satisfactory as an intermediate type.

“That the Machine Gun, Caliber .30, M1919A6, is not a satisfactory light machine gun for infantry use.

“The Infantry Board recommends:

a. “That no action be taken looking at any modification or change in the Machine Gun, Caliber .30, M1919A6.

b. “That development of a more suitable light machine gun for infantry use be pushed.”

It seemed the Infantry Board was talking out of both sides of its mouth. On the one hand, it was stated that the M1919A6 “ … is satisfactory as an intermediate type … .” But in the next sentence stated it “is not a satisfactory light machine gun for infantry use.” Reading between the lines of the Infantry Board report indicates that no more effort should be expended in trying to tweak the M1919A6 any further, and the document closed with the recommendation that the development of a better light machine gun be expedited. As events turned out, this didn’t happen until 1957 with the adoption of the M60 machine gun, which was intended to replace all the Browning .30-cal. machine guns, and the BAR, as standard issue. Throughout its service life, the M1919A6 was designated as “Limited Standard.”

Contracts were placed with the Saginaw Steering Gear Division of General Motors for the manufacture of the M1919A6. In 1944, 23,329 of the guns were made, with an additional 20,150 produced in 1945, for a total of 43,479. It was a simple matter to convert existing M1919A4s to M1919A6 configuration, and kits to accomplish this conversion in the field were produced.

Examples of M1919A4s modified to M1919A6 configuration have been noted with the last digit “4” being defaced and a “6” overstamped. It is not known how many were modified in this way. Also, later in the war, when many of the light tanks were withdrawn from service, the M1919A5 tank machine guns were removed and converted into M1919A4 or M1919A6 configuration, typically with the “5” similarly being overstamped to “4” or “6”.

The U.S. Army airborne units were issued M1919A6 machine guns, as it was felt that the gun would be better-suited for use by the paratroopers since it was lighter and did not require a tripod. They proved to be unpopular with many of its users. As is the case with most “compromise” arms, it didn’t really excel at any one thing. While it fired at a slightly higher cyclic rate than the M1919A4, it wasn’t any more effective in laying down fields of fire than its predecessor. The M1919A4 and the M2 tripod were carried by the gunner and assistant gunner, respectively, and the M1919A6 (which was heavier than the M1919A4 sans tripod) was carried by a single gunner. The M1919A6 could be mounted on the M2 tripod, but that would defeat the entire purpose of the gun. The gun was too heavy to be a true light machine gun, and it didn’t have the stability of a tripod-mounted gun.

There was a reason why the M1919A6 was always designated as “Limited Standard.” While it wasn’t horrendously bad, the M1919A6 simply wasn’t very good at its intended purpose of being a light and easily portable machine gun. There’s nothing wrong with trying to modify a design for uses other than those for which it was originally designed, but that doesn’t mean such efforts will always produce stellar results. The M1919A6’s major, if not sole, advantage was its ready availability. As stated, it was believed that the time required to design, test and manufacture an entirely new light machine gun would have taken too long.

It is a little-known fact that the Ordnance Dept. did embark on a program to produce a virtual copy of the excellent German MG42 machine gun chambered for the .30-’06 Sprg. cartridge. Such a gun would likely have filled the role envisioned for the M1919A6 superbly. However, these efforts did not work out very well. The developmental contract to fabricate a copy of the German MG42, to be designated as the “T-24,” was granted to the Saginaw Steering Gear Division of General Motors.

Like the M1919A6, the gun was envisioned as a replacement for the BAR and the M1919A4 machine gun and was designed so it could be used with the M2 tripod as well. The length of the American .30-cal. cartridge as compared the MG42’s 7.92×57 mm cartridge required that the German design essentially be re-engineered. However, the prototype gun functioned quite poorly in initial testing. It was soon discovered that a draftsman had not properly accounted for the differences in the dimensions between the American and German cartridges, and the receiver was about a 1/4″ too short, which resulted in the numerous malfunctions. The amount of additional engineering work to properly re-design the prototype was not considered to be worthwhile, and the project was canceled. This resulted in the gun being discarded and the M1919A6 being adopted instead. It has been suggested that there was an element of the “NIH (not invented here) Syndrome” involved in the decision to abandon the .30-cal. MG42 project and accept, albeit reluctantly, the M1919A6. It may not have been as good as a properly engineered .30-cal. MG42, but it was felt to be better than the alternative, which would have been nothing.

Like the M1919A4 machine gun it was based on, the M1919A6 remained in service well into the Vietnam War era. It is fair to say that the M1919A6 was not one of the best-loved American arms of World War II, even though the gun’s basic mechanism, the .30-cal. Browning, was held in high esteem. It has been said that the M1919A6 machine gun was akin to the old adage that “a camel was a horse designed by a committee.”

The foregoing was excerpted from the author’s comprehensive work U.S. Small Arms Of World War II. The 8 1/2″x11″ book contains 864 pps. and is lavishly illustrated. Contact: Mowbray Publishing, Inc.; (800) 999-4697; (gunandswordcollector.com).

Owners of the Kimber K6s compact, stainless-steel revolver who have trouble seeing their factory sights or simply wish to upgrade for better front sight visibility, day or night, now have the option of adding the XS Sight R3D Night Sight — a 3-dot tritium notch and post sight.

The R3D front sight is equipped with XS’s proprietary Glow Dot with tritium center for dual illumination. The Glow Dot absorbs ambient light and glows in low light while also absorbing light from the tritium which continually charges the dot. This makes the front sight glow even brighter than the tritium rear sights which drives focus toward the front sight and downrange threat, enabling faster and more accurate target acquisition.

The high-contrast colored front sight is available in Orange or Green. The 2-dot, blacked-out tritium rear sight illuminates to facilitate proper sight alignment without outshining the front sight for accurate indexing.

R3D sights are CNC machined from solid steel bar stock by XS Sights’ in-house machine shop in Ft. Worth Texas and have a 12-year warranty on the tritium.

Gunsmith installation of these sights is recommended for the Kimber K6s as the front sight will need to be drilled for the retention pin. The R3D sights do not fit the Kimber K6xs.

The front sight retails for $73 and the front and rear sight set retails for $138. All XS Sights are backed by XS’s 30-Day Satisfaction Guarantee. For more information, visit XSSights.com.