I recently did two things that I always swore I would never do: spend beaucoup bucks on a bespoke, custom-made firearm and purchase an M1911. Regarding the former, it’s just because I’m an inveterate frugal person who owns exactly one pair of jeans at any given time, cuts his own hair, eats a PB&J for lunch most days, gets a good six months out of a razor and who wears the same pair of $20 shoes until they disintegrate beyond the point of repair.

So I could never mentally justify the notion of spending $5,000 on one gun—even the best gun in the world—when that same amount could be put toward five $1,000 firearms, a dozen value guns or, perhaps best of all, several years’ worth of ammunition.

And concerning the latter, it’s not that I didn’t “get” the M1911—it truly casts a singular shadow across nearly the entire history of the semi-automatic pistol—it’s just that, as someone who has been described on numerous occasions as being “obnoxiously left-handed,” I have always been moderately miffed that the flagrantly right-handed platform’s greatness has never fully applied to me personally. So, sitting here now as the proud owner of a Cabot Guns National Standard South Paw (NSSP)—having violated both of my long-held prohibitions simultaneously—I am probably about as surprised as anyone.

But, over time, my priorities started to shift. With all of my collection’s “needs” long since covered and even most of my “wants” already sorted, I had been searching unsuccessfully for years to find a capstone to my handgun collection. I’ve reached the point in my gun-buying career where quality is now far more important to me than quantity, and if I’m not going to feel some sense of pride in the ownership of a prospective new firearm, then there’s no point in making the purchase. And I’m sure many of you can relate to this—as time goes on, I also find myself less and less willing to compromise with guns that are essentially designed to exclude me, and as great and as seminal as John Moses Browning’s design is, that has always included the M1911.

Right-handed shooters have hundreds, if not thousands, of M1911 options, and can decide to spend however much they want to on one—from $400 on up. Lefties currently have exactly one choice—Cabot’s line of fully reversed, left-ejecting, right-side-controlled South Paws—which requires a slightly higher outlay starting at $5,795. Several years ago I had the pleasure of reviewing one of the NSSP’s predecessors, the S103 Limited South Paw, for the print magazine. I walked away from the experience of testing this truly left-handed M1911 incredibly impressed.

In addition to its gorgeous presentation, the Ransom-Rested gun stacked five-shot groups so tightly that Managing Editor Christopher Olsen and I walked down to the target and honestly wondered where the other four shots had gone—at 25 yards, some “groups” just barely exceeded the 0.452” diameter of the .45 ACP projectiles. As amazing as this experience was, I wasn’t quite ready at the time to shell out the large sum that would have been necessary to make that Cabot my own, but the memory of the gun stuck with me in a way that few reviews I conduct for the magazine do.

And yet, ironically, it was a trip to the range several years later with another manufacturer’s M1911 that would finally get me over the hump and ready to plunk down some serious dough. It was fall of 2021, and after seeing the incredible accuracy that another writer had wrung out of a full-size Springfield Emissary that we had received for evaluation, I felt the need to try that particular gun out for myself. Following a 100-round range trip with the pistol, during which it had again performed phenomenally, I was left with two very distinct, very succinct, impressions.

One, that the actually firing of an accurate, well-constructed M1911 ranks high among the most pleasant experiences a shooter can have with a handgun at the range. Unfortunately, along with it came, two, that the blatant right-handedness of the design makes it infuriatingly inconvenient at best and downright unsafe at worst for southpaws to manipulate—let alone carry—a stock, right-handed M1911.

It was this stark dichotomy of enjoyment and frustration, not to mention the fact that Editor In Chief Brian Sheetz—fully aware of how proudly I wear my left-handedness on my sleeve—had been cajoling me for years to pull the figurative trigger on a South Paw, that finally convinced me to give Cabot CEO Rob Bianchin a call. Together we ironed out the details. Cabot is, after all, the custom gunmaker known for offering firearms in a truly mind-boggling assortment of construction materials—from Mosaic Damascus steel made from the literal original suspended cables used to build San Francisco’s famous Golden Gate Bridge back in 1933 to fragments of the literal Gibeon meteorite that crashed to Earth in Namibia during prehistoric times. Yes, really.

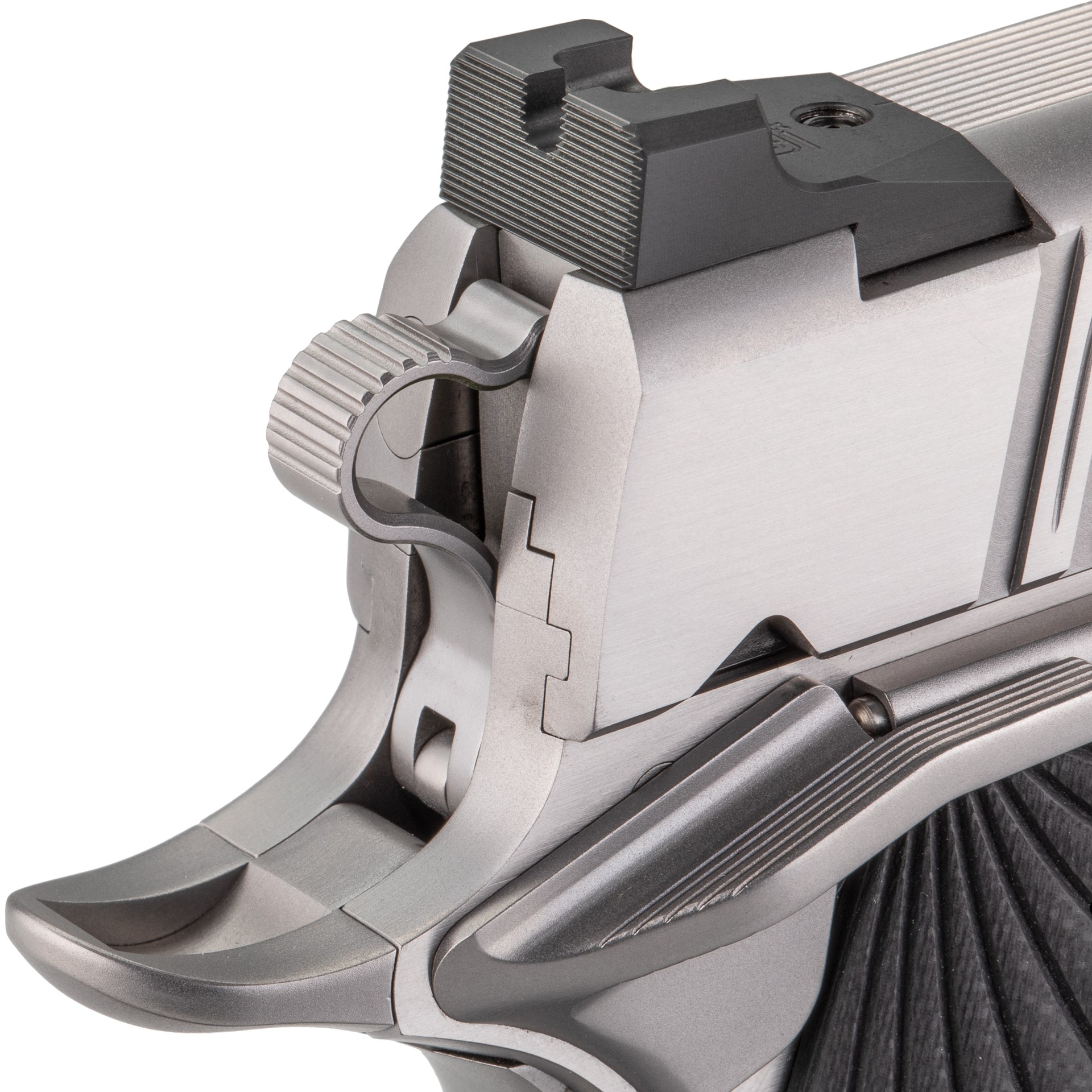

I elected to keep things simple, relatively speaking. I went with a 5”-barreled Government Model (although Cabot does also offer full-cycle Commander South Paws) in normal, non-Golden-Gate-Bridge 416 stainless steel, with G10 stocks that feature a company medallion and concentric Fibonacci spirals. For the rear sight, I decided that the base option of the Cabot Ledge, a black-out and serrated U-notch unit, would suffice for my needs—although I did splurge (further) with a gold-bead front sight and a custom serial number of my own choosing. While the company can chamber its M1911s for a variety of cartridges, all South Paws are .45 ACP. I’m sure that a left-side thumb safety would have been an option, but if you think I was willing to spend an additional cent to make my pistol even a scintilla more right-hand-friendly, then you clearly missed the point of the exercise.

Upon wrapping-up with Rob, I also initiated the process of picking out and selling four guns from my collection that weren’t being used enough to justify keeping them around, as I did not yet have anywhere near enough gun money on hand to make a purchase of this magnitude. From the time that I ordered it to the date of its arrival at my dealer’s FFL, my NSSP took right at 18 months to complete. The first year I quite successfully swept it from my mind—which is always my advice for custom work, suppressors and taxidermy—but the last six months were pretty excruciating. It arrived wrapped in a red velvet sock inside a plush carbon-fiber box, along with a certificate of authenticity, an owner’s manual, two eight-round magazines, a spent case, a cleaning cloth, a bushing wrench and a cable lock.

Unlike some custom M1911 makers who hang their hats on the angle of one master gunsmith using hand tools to file one gun at a time into its final shape, Cabot’s claim to fame—beyond the borderline-ludicrous construction materials mentioned above—is the amazing precision with which its pistols are built and finished using automation. Five-axis CNC machines cut mating surfaces with microscopic tolerances, and parts are produced with such minute conformity as to essentially be clones of each other—resulting in fit that essentially can’t be improved upon.

Cabot NSSPs are built from the ground up to be true mirror images of the company’s right-handed National Standard models, which requires that left-handed versions of nine components be fabricated—the frame, slide, slide stop, thumb safety, grip safety, sear spring, magazine release, ejector and extractor—in addition to left-handed magazines compatible with a reversed magazine release button. And, since it is the only southpaw M1911 company in the game, this means that Cabot must make all of these pieces in-house itself.

Port-side ejection is a great perk and all, but, truth be told, right-handed pistol designs rarely send their empty cases on an intercept course with their left-handed shooters, and M1911s, in particular, have never presented a problem for me in this regard. No, the real appeal of the NSSP (beyond the principle of it) are the changes made to the frame—moving the slide lock, magazine release button and one-sided thumb safety to the right (and correct) side of the gun. Man, it’s amazing how much a man will pay for a slide stop he can actually use… .

Beyond the obvious left-handedness, when looked at from 30,000 feet, this is seemingly a traditional Series 70 Government Model M1911. But, as each part is examined at the granular level, you’ll see that a good many of this gun’s components have either been functionally improved in some form or fashion compared to what we’ve come to expect of the M1911 platform or at least bear some sort of decorative adornment that elevates it above production-gun status.

To name just a few examples: Rather than employ a traditional, side-cut dovetailed front sight, which can walk to the left or right over time and alter your zero, the NSSP’s front sight is instead press-fit into a dovetail cut into the front of the slide and is held in place by the barrel bushing, a novel method of ensuring it never wanders. Likewise, instead of simply staking it in place after the frame rails have already been cut, Cabot’s ejectors are drilled and pinned in place first and then machined alongside the frame rails, resulting in an uncommonly seamless integration of the two parts.

Cabot has also re-designed its slide stop to help the owners of its guns avoid the dreaded “idiot scratch.” By simply machining a groove into the slide stop’s lug that is easily located by the tip of the plunger, the slide stop can be pushed straight into place during re-assembly without fear of it twisting downward and raking itself along the side of the frame. A deeply chamfered edge around the hole in the frame through which the tip of the slide stop is visible also allows the part to be removed (once the slide and frame are aligned properly, of course) effortlessly using just your fingertip without it needing to stand proud of the frame.

One of my favorite features on the NSSP is what Cabot calls the rhombus-style checkering on both its frontstrap and flat mainspring housing, which I have found to be a best-of-both-worlds design. Unlike some makers that cut patterns into their grip frames so aggressive that your hand is guaranteed to bleed by the end of even a mildly long range session, the company’s 24-l.p.i. rhombus checkering doesn’t feel sharp at all if you simply run your fingers across it. And yet, similarly to the tread on your vehicle’s tires, it is engineered to grip your palm more tightly under the torqueing motion of a recoiling gun, and then release hold again once control has been regained. As a result, the pattern feels good both when you’re firing and when you’re not, while being entirely practical.

The NSSP’s single-action trigger bears special mention. I have handed my gun off to several veteran gunwriters since it has arrived—after all, watching righties whine about how inhospitable the “backwards” controls are is one of the prime benefits of owning it—and, after a few dry-fires, more than one have characterized its break as “perfect.” I can’t disagree. There’s 1/16” of take-up before resistance is met, with the sear then releasing at 3 lbs. even (which I had to go analog with an old Ametek Hunter Sprung L-30 mechanical gauge to confirm because the results were too light to register on my digital gauge), with a level of cleanness that shooters dream about.

The company website states that Cabot M1911s come with an accuracy guarantee of better than 1.5” groups at 25 yards—which seemed to me to be an incomplete thought—as a 1.5” two-shot group is infinitely easier to pull off than a 1.5” 10-shot group. So I asked Rob to clarify whether this pledge applied to a fairly standard testing protocol like three- or five-shot groups, or something more ridiculously outlandish like maybe 10- or 25-shot groups, and his answer said it all: “yes.” As mentioned above, the S103 Limited South Paw previously tested for work easily met that 1.5” standard during a full formal accuracy protocol while installed aboard a Ransom Rest.

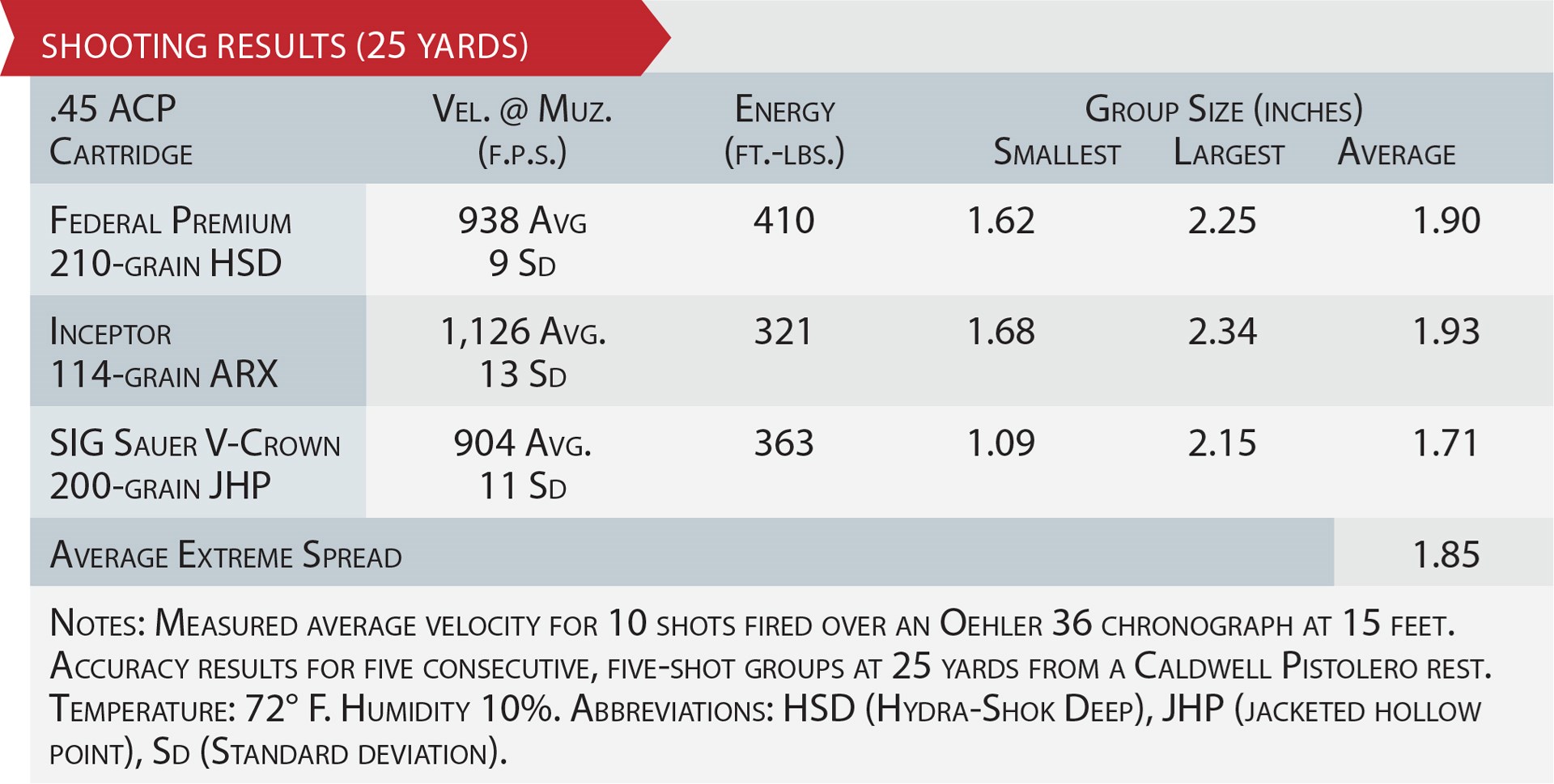

And while I haven’t gone through that whole rigmarole of pulling the Ransom Rest out of the closet and installing it to the bench in order to validate Cabot’s claim, groups shot at 25 yards from a Caldwell Pistolero seem to indicate that my personal gun’s accuracy is equally impressive. Using Federal’s 210-grain Hydra-Shok Deeps, Inceptor’s 114-grain ARXs and SIG’s 200-grain V-Crowns, I managed a 15-group average extreme spread of 1.85” using five-shot groups. SIG’s JHPs produced both the tightest group of the day (1.09”) and the smallest five-group average (1.71”). I am far from the world’s best handgun shooter, and these results are quite good for me, so I can only imagine how much these groups would shrink if all human error were removed from the equation. But there is a down side—between its dead-nuts accuracy and a sublime trigger that doesn’t get in the shooter’s way at all, I can know with depressing confidence that any missed shots taken with this pistol are entirely my fault. Through approximately 400 rounds at this point, functioning has been 100 percent.

In my opinion, the modern M1911 is the most aesthetically pleasing pistol ever designed, and the Cabot NSSP is prettier than most—however, I will admit that it did take my brain a while to acclimate to the ejection port being on the proper side of the slide. Apart from this brief period of mental adjustment, the gun truly is immaculate. My pistol’s satin-polished flats meet perfectly with its bead-blasted rounds, without the need for a French border, and the finishes throughout are without flaw. Decorative touches added to the handgun—like the three stars wire EDM cut through the side of the curved trigger, the star imprinted into the tip of the full-length guide rod that is visible through a hole in the recoil spring plug and the delicate feathering added to the cocking serrations—are attractive but understated.

If I were forced to voice a gripe, my only real peccadillo regarding the NSSP would be leveled at the abovementioned cocking serrations. Their corners are so sharp that it has proven to be quite difficult to keep the serrations clean, as it only takes a few manipulations of the slide for a discernible amount of my palm/finger skin to be sheared off and deposited within the corners of these five small grooves. It’s not at all painful—it’s just kind of a gross maintenance consideration to be faced with for such a refined firearm.

It’s going to be difficult for right-handed shooters to appreciate how attached I’ve become to this gun over a relatively short period of time. This is because in your safe right now is an assortment of handguns that were designed from inception to accommodate you and likely not a single one that requires an iota of compromise on your part in order for you to safely and competently operate it. The Cabot National Standard South Paw is the exact opposite for me—it is literally the only no-compromise handgun I own. And it is for this reason that the pistol’s beauty to me is far more than just skin deep—it is not only a phenomenal pistol by all objective measurements, for me, it also represents the principle of no longer being forced to settle for a northpaw’s gun. Which, as an obnoxiously left-handed shooter, it turns out is virtually priceless.

When reviewing expensive, bespoke firearms like this one, the question inevitably becomes, “Is it worth the money?” In years past, I have always felt uneasy about answering that question in my capacity as an editor for the magazine, because it has never before been my money being spent, and it can be real easy to get prodigal with someone else’s cash. Well, this time, it was my money, and the answer is still a resounding “yes.”

On more than one occasion I have pined over a gun and then immediately suffered buyer’s remorse when I got it home and it didn’t quite live up to the expectations. Despite my frugality—and the fact that the Cabot literally costs more than my next three most expensive guns combined—I have had zero regrets whatsoever about adding it to my stable. I was seeking a singular capstone, and that is exactly what I got. Its fit, its finish, its accuracy, its engineering and its artistry are all exquisite—as is how perfectly its obstinate left-handedness matches my own.

Sure, a company deciding to come to market with a left-handed production pistol at a more reasonable price point is still a consummation devoutly to be wished, but until that glorious day comes, I no longer have to “make do” with someone else’s gun. However, now that I’ve had a taste for how the other 90 percent lives, a small (but growing) voice in a back corner of my mind keeps asking, “Do I also need the full-cycle Commander?”

Cabot National Standard South Paw Specifications

Manufacturer: Cabot Guns

Action Type: recoil-operated, semi-automatic, centerfire pistol

Chambering: .45 ACP

Slide: 416 stainless steel

Frame: 416 stainless steel

Barrel Length: 5”

Rifling: six-groove; 1:16” RH-twist

Magazine: eight-round detachable box

Sights: drift-adjustable U-notch rear, fixed gold-bead front

Trigger: single-action; 3-lb. pull

Overall Length: 8.63”

Height: 5.75”

Width: 1.34”

Weight: 39.2 ozs.

Accessories: owner’s manual, presentation case, extra magazine, cleaning cloth, bushing wrench, lock

Base Price: $5,795