It was an arms race and Winchester was way behind. In 1873 the U.S. Military made the single-shot .45-70 Springfield Trapdoor their standard rifle. The same year the Springfield Trapdoor was issued, Winchester introduced their Model 1873 lever-action rifle in .44-40. At the time, the .44-40 was a powerhouse. The .45-70 dwarfed it, but no repeating rifle could handle the round — yet. The race was on.

Three years later, Winchester offered the Model 1876. The ’76 sold in a wide range of powerful cartridges, but none were the .45-70. Some claim the pins of the toggle-link system of the ’76 couldn’t handle the energy of the larger cartridge but in reality, the geometry of the toggle-link system limited cartridge length. The ’76 was just a larger version of the Henry, the ’66 and the ’73. Making an even larger receiver would make the rifle ungainly.

Meanwhile, Marlin …

In 1881 Marlin came out with their first repeater, the Model 1881, with an action long enough and strong enough to handle the .45-70 with ease and grace. The military was impressed and included the Marlin 1881 in their trials. The rifle performed well and, in one test, fired 10 shots in seven seconds! But the rifle suffered a catastrophic failure when a cartridge went off inside the magazine tube. The failure and other issues killed any interest by the military.

In the mid-1880s, a new “white” powder came on the market. Besides being smokeless, the powder generated much higher pressures and velocities than black powder. The pressure was on Winchester to produce a rifle in keeping with the recent developments.

As luck would have it, Winchester’s vice-president Thomas Grey Bennett paid a visit to John Moses Browning to purchase the rights to what would become Winchester’s Model 1885 single-shot rifle. During the visit, Browning showcased a new design for a repeating rifle. The concept was different from Winchester’s toggle-link design — long enough and strong enough to handle the .45-70 and then some. Bennett leaped at the opportunity and paid Browning $50,000 (equivalent to $1.5 million today) for the exclusive rights to what would become their Model 1886.

Browning’s design did away with most of the weaknesses of Winchester’s previous lever-action rifles. The biggest was the ability to chamber the longer cartridges like the .40-82, .45-90, and of course, the .45-70 Government.

The design of the ’86 also did away with the weaker toggle-link system. In many ways, the new design used the strengths of the old falling block rifles like the Sharps.

The ’86 split the falling block design into two interlocking lugs keyed into the bolt and the receiver.

The pesky dust cover was no longer needed because the bolt was sealed against the barrel face. And the moving brass elevator also vanished as everything was done internally, eliminating an entry point for dirt and debris.

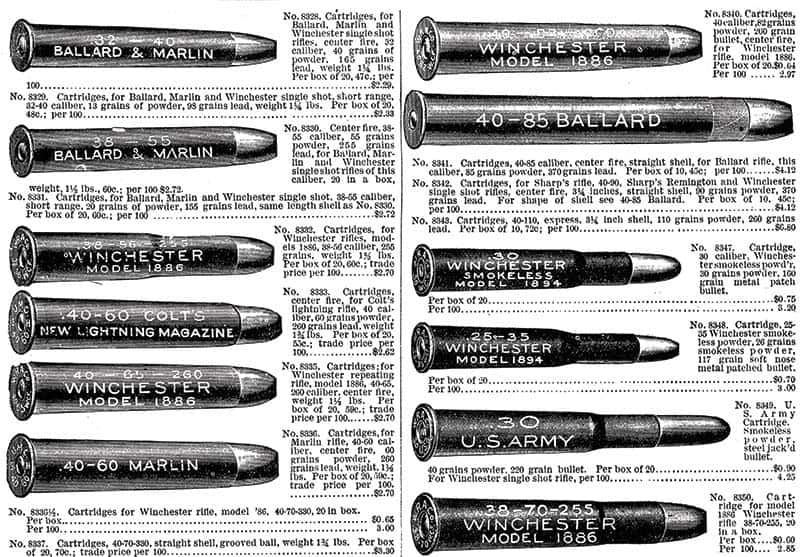

The .45-70 was the most important chambering, and the ’86 could handle both the 405-grain load and the shoulder-bruising 500-grain load. Winchester also offered the .40-82-260 and the .45-90-300 in a slightly longer case. Their designation was the caliber, powder charge and bullet weight. As time went by, they added the .38-56-255, .38-70-255, .40-65-260, .40-70-330 based on the .45-70 and .45-90 case. (The case head was the same, but the cartridges varied from 2.1″ to 2.4″ in length.) Because of the ability to handle long cartridges, Winchester even offered a .50-100-450 and a .50-110-300. They were essentially the same cartridge with different bullet weights.

The ’86 was big medicine and an instant hit with scouts, hunters, lawmen, bandits and Native Americans. It was the rifle made for the West. In a suitable chambering, it could handle bison, elk, grizzly bear, moose and more. For proof, one has to look no further than Dr. William Allen’s journal Adventures With Indians and Game. In it, he related his hunting in the wild Rocky Mountains, during which he proved the worth of the ’86 against the single-shot rifles of his companions.

Teddy Roosevelt was a huge fan of Winchester rifles from his youth. He liked big-bore guns and used them for hunting in the American West and Africa. The 1886 rifle was one of his favorites due to the powerful cartridges and the rapid follow-up shots. Roosevelt was a man of high taste and carried a deluxe .45-90 version with many custom features. He used his 1886 extensively and set it back to Winchester to be refinished five times!

Roosevelt also gifted Winchester 1886 rifles to those people he admired.

In 1895 Winchester started offering their rifles with the new, more robust nickel steel to handle the new smokeless powders. The barrels were marked “Nickel Steel” or “Winchester Proof Steel.”

The Winchester ’86 even saw service in WWI. Great Britain purchased Winchester rifles in .45-90 to use in their defense against German Zeppelins. Special incendiary cartridges were developed to ignite the hydrogen-filled airships.

After producing just under 160,000 Model 1886 rifles, Winchester ended the model in the mid-1930s. But almost immediately, they revamped the design to handle the powerful .348 Winchester cartridge, calling it the Model 71. The Model 71 lasted until the late 1950s and brought the total up to 200,000 rifles.

With America’s love affair with the Old West renewed in the Golden Age of TV and silver-screen westerns, collectors started snatching up any originals available. These days, rifles with no rifling still command a hefty figure.

Luckily, in the 1980s, Browning contracted with Miroku Firearms in Japan to produce a new generation of ’86s and not long after, Italian companies started offering them as well. Now, shooters wanting to carry an 1886 in the field for bear, moose or elk, or compete in long-distance cowboy matches, can do so without worrying about degrading a piece of history.

Miroku, Pedersoli, Uberti and Chiappa offer their versions of the venerable ’86. But, shooters need to be aware of some limitations and changes that can impact their use. There have been production runs made for “Black-Powder Only.” Some makers have added a thumb safety the originals didn’t have. If you’re using the rifle for hunting, the safety has value. If the gun is used in competition, the safety can cause problems if it is accidentally engaged.

Like the originals, the new offerings come in many configurations, including a pistol grip, shotgun buttstock, round barrel, octagon barrel, carbine length, rifle configuration, crescent buttstock, etc. The calibers also vary, with the .45-70 being the most common, but there are .45-90 rifles out there for those who enjoy just a little bigger shoulder bruise.

Keeping Score

When I went shopping for a new 1886 for use in competition, I decided on the model made by Chiappa and offered by Cimarron Firearms in .45-70. It has the same straight stock and 26″ octagon barrel configuration the originals had, so it only takes a little eye squinting to make me feel I’m back in the Old West. The color-case hardened frame is spectacular. Many competitors use a tang-mounted peep sight, which gives them the edge over traditional buckhorn sights. Luckily, the Cimarron Arms 1886 receiver comes tapped for tang sights.

The .45-70 with 26″ barrel and full-length magazine holds eight rounds so I only need to load two rounds on the clock. While shorter magazines are available, it means more time spent reloading on the clock.

While I use my rifles in speed competitions, the same attributes I want are beneficial for hunting. I have an original Winchester 1886 made in 1890, and just holding it makes me giddy with the history it has experienced. I get much of the same feeling with my new ’86. Hopefully, we have a long history of being in the winner’s circle.