The war between Iran and Iraq started in 1980 when Saddam Hussein sought to take advantage of Iran’s chaos by conquering and annexing Iran’s oil-rich Khuzestan province, and in the larger sense, destroying the Iranian islamic regime’s military. In turn, the Iranians sought to first repulse the Iraqi attack and then knock Hussein out of power and replace him with an Iraqi theocratic government modeled on Iran’s.

The war ended up lasting eight years and was one of the worst of the 20th century. For the most part, Iran employed high-tech systems like the MIM-23 Hawk SAM and AH-1 Cobra attack helicopter, but there were some WWII weapons in Iran’s use as well.

(Iranian WWII-vintage M4 Sherman and M36 Jackson on the front lines of the 1980-1988 war.)

(Iranian WWII-era M115 artillery during the 1980-1988 war against Iraq.)

Iran during WWII

Iran had sought to stay neutral in WWII. However the British and Soviets both realized that the Iranian railway system would be ideal to move supplies to the USSR via the Persian Gulf. Additionally Churchill saw Iran as a possible ‘captive supplier’ of oil, while Stalin was open to annexing part of Iran to the USSR. On 21 August 1941, the two countries attacked and occupied the country. Shah Reza Khan was forced from the throne and replaced by pro-western Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

(the last Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi)

After the USA entered WWII, the US Army built airfields in the country to support Lend-Lease to the USSR. One of the WWII American commanders in Iran was Gen H. Norman Schwarzkopf Sr. In a fluke of history, his son Norman Jr. would command the coalition against Iraq on the other side of the Persian Gulf 45 years later.

(American warplanes at Gali Morgheh airbase near Tehran during WWII. After the war it was renamed Mehrabad airbase. During the 1980-1988 war, F-14 Tomcats of the Iranian 72nd tactical fighter squadron flew from this facility.) (official US Army photo)

WWII in Europe ended in May 1945. The US contingent withdrew in 1945. The British withdrew in the spring of 1946. The Soviets did not withdraw until a year after WWII’s end, and then only under the possibility of a war with Iran.

The revolution and new islamic army

In 1978, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi faced increasing domestic protests and in some cases, outright revolt. There was not one single cause. Contributing factors were his “White Revolution” effort to secularize Iran, unemployment, the alliance with the USA which Iranians viewed as one-sided, overspending on the military, the Shah’s trade deals with Israel, and abuses by SAVAK, the Shah’s secret police.

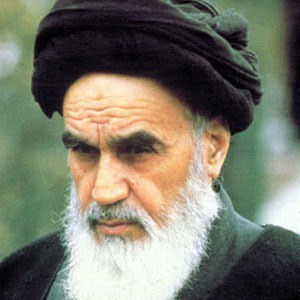

(Ayatollah Khomeini)

On 16 January 1979, the Shah fled into exile and was replaced by a theocratic government led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The change in Iran could have not been more drastic. The country went from being one of the most modern middle east countries to being the most backwards. Khomeini was virulently anti-American and the US embassy in Tehran was sacked, in return a weapons embargo was placed in Iran, crippling it’s military.

(Iranian troops using machinery imported before the 1979 revolution to make knockoffs of the WWII American Mk2 pineapple grenade during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq.)

The Iranian military suffered greatly after the revolution. Thousands of officers and NCOs were jailed or executed. The army was reorganized into seven divisions, an airborne brigade, seven independent brigades, and several smaller independent units. All were understrength due to Khomeini’s purges, and all suffered from a lack of spare parts due to the embargo. The air force fared even worse. Khomeini viewed it’s pilots as irreversibly tainted by American influences and the ranks were thoroughly purged. Had Iran’s air force started the 1980-1988 war against Iraq with a full cadre of trained pilots and full spare parts and munitions, the 8-year war would have probably ended with a defeat of the Iraqi invasion in the first or second month.

A new organization in 1979 was the Iran Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC). Independent of the army but parallel to it, the IRGC is sometimes compared to the Waffen-SS of WWII. This is crude but not inaccurate. The IRGC swears allegiance to the islamic regime, not the country as a whole. At the start of the 1980-1988 war, it was ill-equipped with poor leadership, but by the end of the war had basically become an equal second army. Today in 2016, it is more powerful than the army itself and operates everything from tanks to warships to ballistic missiles.

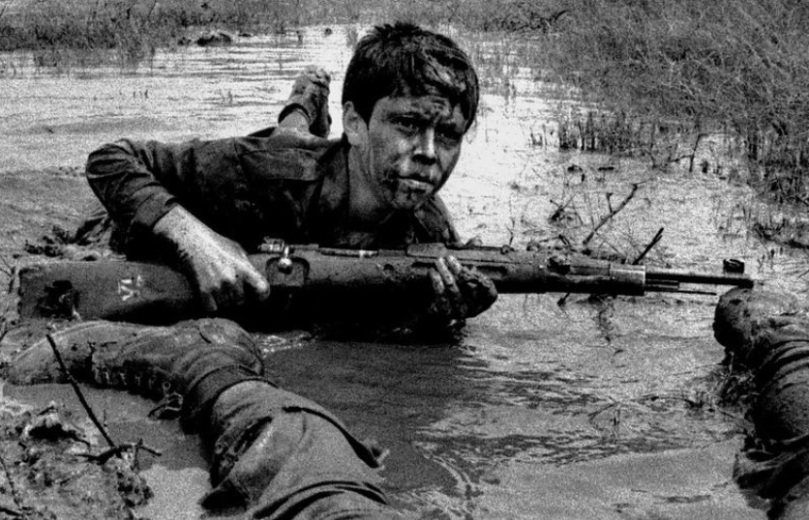

Finally there was another new organization in 1979 called the Basij (resistance force). The Basij was extremely poorly-equipped and poorly-trained during the war against Iraq. It was manned mostly by fanatics drawn from rural villages and the urban poor. To say it’s tactics were poor is an understatement, for example during Iran’s failed July 1982 Basra offensive, thousands of Basij volunteers were mowed down by Iraqi machine guns as they charged in a human wave in broad daylight. The Basij was notorious for it’s use of child soldiers. It is estimated that between 1980-1988, 95,000 Iranians under the international-standard military age of 17 were wounded, KIA, or taken POW.

FIREARMS

the M2

One of the most famous machine guns of all time, the Browning M2 .50cal has been an American standard from WWII to the War on Terror. Deliveries to Iran began in the 1950s and did not end until the Shah’s ouster in 1979.

(Iranian “Ma Deuce” gunner during the 1960s.)

The version supplied to Iran was the M2HB, used mainly as a vehicular weapon and less commonly as an infantry gun. This machine gun fired the 50BMG cartridge (12.7x99mm, 2,978fps muzzle velocity) from M2 or M9 link belts. The 50BMG’s 700gr bullet is extremely destructive, and could penetrate armored personnel carriers. Using the short-recoil system and firing from an open bolt, the rate of fire was 600rpm. With basic iron sights the accurate range was about 1 mile although the maximum range was slightly over 4 miles. The M2HB could be used against aircraft below 4,500′, which was it’s main role with the Iranians.

This machine gun was in full service with Iran at the time of the 1979 revolution and remained so throughout the 1980-1988 war against Iraq.

the M1919

This general-purpose machine gun was used by the USA during WWII and the Korean War. This air-cooled machine gun fired the .30-06 Springfield cartridge from 250-round belts, with a cyclical 600rpm rate of fire.

Iran obtained these machine guns, specifically the M1919A4 version, along with it’s M1 Garand buy. Some were still in service at the time of the 1979 revolution.

the M-1310 aka “Persian Mauser”

This was the Imperial Iranian army’s main battle rifle during the WWII era and well into the Cold War era. Manufactured by Brno Arsenal in Czechoslovakia, it was based on the general Mauser Gewehr 98 of the First World War, and more specifically, the Czechoslovak army’s vz.24 which entered service in 1924.

This rifle’s official Iranian designation M-1310 denotes the year it was accepted for service using Iran’s old imperial calendar (1310 SH = 1931 AD). When the Shah was overthrown in February 1979, this was replaced by the islamic calendar however the Mausers still in inventory were not redesignated. In service, Iranian soldiers invariably just called it the “Bernoh” in reference to it’s origin.

The Iranian rifle was in most respects identical to the Czechoslovak vz.24. It weighed 9 ¼ lbs and was 3’7″ long. It was a bolt-action rifle firing the 7.92x57mm Mauser cartridge with 2,493fps muzzle velocity. This rifle had a 5-round internal magazine, top-loaded via a stripper clip. The M-1310 did not have an empty-magazine bolt holdback, and the gun cocked upon opening the bolt. The rifles were delivered factory-blued and were made to exceptionally high craftsmanship. The long M98/29 bayonet was used.

The adjustable rear tangent sight was graduated in 100-meter (109¼ yards) increments out to 2,000 meters (1¼ miles), in Farsi numerals. The dovetailed front sight could be adjusted for windage and had steel wing protectors. The M-1310 was very accurate.

(Brno Arsenal proof firing target counterstamped by an Imperial Iranian army observer.)

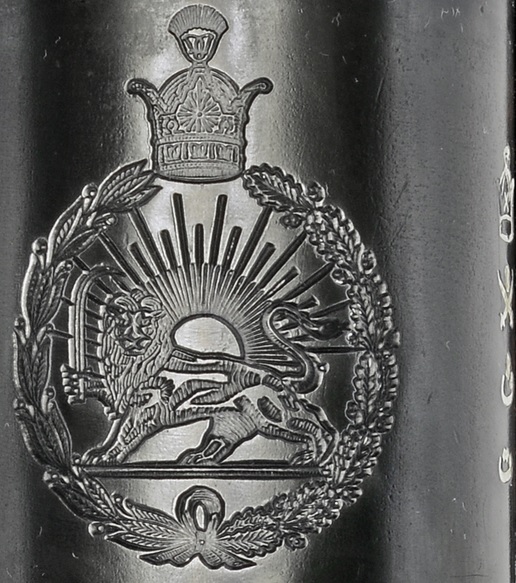

The M-1310s had the imperial crest on the top of the receiver. On the right side, is the model nomenclature in nastaleeq (Farsi calligraphy), the crossed swords proofmark, and the imperial crown signifying state property.

The M-1310 was one of the Imperial army’s main rifle types during the 1941 Allied invasion, and following the end of the occupation in 1946, was the sole battle rifle until Garand deliveries began.

(Iranian MPs with M-1310s arrest a suspected deserter in 1955.)

(Iranian soldier with M-1310 in the early 1970s illustrating the sling technique for better accuracy. Helmet is the WWII-era M1 steel pot.)

(Iranian Gen. Akbar Compani reviews the Imperial Air Training Command in January 1973. The rifles are M-1310s with M98/29 bayonets.)

(An Imperial air force review with M-1310 rifles in the late 1970s. The officer is Gen. Nader Jahanbani, a highly skilled general who was instrumental in convincing the USA to export the AIM-54 Phoenix missile and F-14 Tomcat fighter to Iran. Gen. Jahanbani was murdered by the new islamic government in 1979.)

Iran probably would have continued ordering even more of these rifles had it not been for the German annexation of Czechoslovakia and then WWII. A very small number were manufactured in Iran between 1946-1949, before domestic production switched entirely to the Kootah carbine version. Meanwhile the 7.92mm Mauser ammunition was manufactured locally in Iran.

(Headstamp on an Iranian-made 7.92mm Mauser round and it’s wooden ammunition crate.)

the M-1317 Kootah

This was a carbine version of the M-1310. Unlike the rifle, the carbine was made domestically in Iran using Brno’s blueprints and machinery supplied by Skoda in Czechoslovakia after WWII. The popular name, Kootah, simply means “short”. This weapon was approved for production in 1317 SH (1946 AD, and is sometimes called the “Model 46 Mauser” in English) and entered full service in 1949.

The main difference was a reduction in size and weight, the Kootah being 14% lighter, mainly by shortening the barrel by 5″. This followed a WWII trend of downsizing service rifles; such as the M38 and M44 versions of the Mosin-Nagant 91/30 and the 98k version of the Gewehr 98. The carbine was less accurate which the Iranians considered inconsequential, as WWII had showed that few infantry engagements took place beyond 450 yards. One side effect was that the 7.92 Mauser round’s recoil was felt more substantially due to the weight reduction. Other than the obvious size difference, the most notable change was the downturned bolt.

(Markings on the turndown-style bolt of a Kootah.) (photo via Liberty Tree Collectors)

(Female soldiers of the Imperial army march with Kootah carbines in the 1970s.)

(Female officers of the Shahrbani (national police force) in the late 1970s with Kootah carbines, which shared the long rifle’s bayonet type. Despite it’s association with the ousted Shah, the Shahrbani was retained in a truncated, islamicized (and all-male) form by the Khomeini regime after 1979. Patrolmen of the Shahrbani fought the invading Iraqis on the streets of Khorramshahr in 1980 and helped break the 10-month siege of Abadan in September 1981. The Shahrbani was disestablished in 1991.)

the M1 Garand

The semi-automatic M1 Garand was the main battle rifle of the United States during WWII. It was 3’8″ long and weighed 9½ lbs, firing the .30-06 Springfield cartridge (2,800fps muzzle velocity) from an 8-round internal enbloc. It had adjustable rear sights and a front post sight with protective wings. All-around, this was perhaps the best infantry rifle of WWII and one of the most classic firearms of all time.

Iran obtained a total of 165,525 M1 Garands. The first lot of 66,493 was ordered and delivered in 1963. The second lot of 99,000 was ordered immediately thereafter and delivered between 1963-1966. Finally, in 1966 a small lot of 32 of the M1D sniper version were delivered. All were obtained through the Security Assistance Program (SAP) and were WWII-production surplus guns drawn from US Army warehouses. No additional markings were put on the guns and they were indistinguishable from American examples at delivery.

(Imperial Iranian army soldiers drill with the M1 Garand in 1971.)

(Imperial Iranian army instructor explains the M1 Garand in the mid-1970s.)

The Garand immediately replaced the old Mausers as the Iranian army’s main battle rifle, a role it held until the mid-1970s. Thousands were still in Iran’s inventory at the time of the 1979 revolution.

(Female cadet of the Imperial air force with a M1 Garand on the cover of a late 1970s magazine. Women’s progress in Iran came to an abrupt end with the Shah’s departure in 1979.)

Iran domestically manufactured bayonets for their Garands. The Iranian bayonet had a 1″-wide, 9½” steel blade with wooden handle. The Iranian-made scabbard was a close copy of the US Army’s M7 design. The Iranian bayonets were marked with the crossed swords proofmark and royal crown; some also had a crescent which may have been a manufacturer’s mark.

(Iranian-made Garand bayonet.) (photo by Bill Porter)

During the 1980-1988 war, these bayonets were not always issued in unison with the remaining M1 Garands and some were used as general combat knives. Iranian M1 bayonets are very rare today in 2016.

Iran domestically manufactured .30-06 Springfield ammunition. Following the Imperial army’s conversion to the G3A6 assault rifle (7.62mm NATO), Iran began to discard it’s .30-06 stockpile. In the late 1970s some was exported to the USA’s civilian market where .30-06 is a popular hunting caliber; this sales effort was of course ended by the 1979 revolution. Iranian .30-06 ammo still appears for sale from time to time in the USA today in the 21st century. Most shooters consider it of substandard quality.

(Iranian-made .30-06 Springfield ammunition.)

the M1 carbine

Iran received 57,863 M1 carbines in 1963, all WWII-surplus, ex-US Army stock. This carbine (unrelated to the M1 Garand rifle) was 2’11½” long and weighed 5¼ lbs empty. It fired the .30 Carbine cartridge (1,990fps muzzle velocity) from a 15- or 30-round detachable magazine. It was effective out to about 300 yards.

The M1 carbine was not popular in Iranian service. By the time it was integrated into use in the mid-1960s, full-auto assault rifles were common worldwide and a semi-auto carbine was an inferior weapon. The Iranians considered the .30 Carbine cartridge too puny for distanced shooting and the gun itself too big for close-quarters use. Additionally, it’s ammo was uncommon to any other Iranian weapon. Iran generally replaced this gun with the Uzi submachine gun, thousands of which were bought by the Shah when Iran and Israel were allies before the 1979 revolution.

the M-1314 Luger aka “Persian P08”

These pistols were from a deal negotiated by Gen. Ism Khan, Iran’s defense attache to Europe before WWII. A total of 3,000 were originally ordered in 1935. Of these, 2,000 of the standard 95mm barrel model and 980 of the 200mm barrel artillery model were actually delivered. Both models had the ‘crowned U’ German proofmark and markings in Farsi. The last were delivered in June 1936.

(The Iranian artillery model M-1314.) (photo via Guns America website)

The artillery model was identical to the First World War “lang Luger” of Germany, and used the same holdopen latch, walnut grips, leather holster, and wooden stock. The only difference was the use of the later-style thumb safety.

The standard model was less elaborate and came in a cardboard box with cleaning rod.

For whatever reason, not all of these pistols were issued. It wasn’t uncommon for American defense contractors in the 1960s and 1970s to receive them as gifts, often unfired. The artillery models were apparently usually given to senior officers for dress uniform wear. Some were personalized with aftermarket ivory grips or gold gilding. The standard models were usually reblued by the 1970s, for those which had made it into service.

(This standard-model 1935 Persian Luger was unused when gifted to US Army Maj.Gen. Vernon Evans by the Shah in 1951. General Evans had helped modernize the Iranian army.)

the M1911

Along with the M1 Garand buy, Iran imported some of these handguns from the USA. Perhaps the most iconic semi-auto pistol of all time, the M1911 was 8¼” long and fired the .45ACP (825fps muzzle velocity) cartridge from a detachable 7-round magazine.

Iran’s guns were all of the M1911A1 version, and all WWII-production ex-US Army stock. They were marked in the typical American military way and indistinguishable from any other M1911.

The M1911’s tenure as the main Iranian sidearm was not long, as during the late 1960s Iran began importing Italian semi-autos. None the less, many M1911s were still in use at the time of the 1979 revolution.

oddballs

A surprising handgun in the 1980-1988 war was the Smith & Wesson Model 10. These had been used, as the Victory Model, by British forces in Iran during WWII with some left behind. These were joined in the 1940s and 1950s by the M&P version, issued to Iranian police. As the Iraqi war went on, some of these were transferred to the army or Revolutionary Guard. After the 1988 truce, the survivors were given back to civilian police in Iran, where some are still in use in 2016.

The above photo shows an Iranian soldier during the 1980-1988 war with a M3 Grease Gun of WWII American manufacture. Not a standard type during the Shah’s era, this .45ACP weapon might have been a WWII leave-behind, or provided by Vietnam, or obtained on the black market.

The above photo shows an Iranian first sergeant with a M97 “trench cleaner”. This pump-action 12ga shotgun was used by the US Army and US Marine Corps during WWII, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. It’s perforated barrel shield and lug for M1917 bayonet gave it a fearsome appearance. Almost certainly, Iran obtained this shotgun from Vietnam. During the 1980s, the Iranians bought various American-made war goods from the Vietnamese, which had inherited them at Saigon’s fall in 1975. More common than shotguns were spare parts. During the 1980-1988 war, the anti-American Ayatollah’s UH-1 Iroquois helicopters were kept running by spare parts that the USA had intended to bolster the now-defunct South Vietnamese military.

replacement of WWII-era firearms

In the early 1970s, Iran imported several thousand G3A4 rifles from West Germany in preference to surplus American M14s. A production license was granted by H&K for a version called G3A6, which entered production shortly before the Shah’s ouster at Mosulsalasi Arsenal in Iran. In 1977-1979, this factory was making 145,000 G3A6 rifles per year, which was sufficient to have phased both the Mausers and Garands out of service with main frontline infantry divisions, although thousands of Garands still remained in daily use throughout the army. There was a minor cash buy of AK-47s (along with RPG-7 rocket launchers) by the Shah from the USSR late in the 1970s; this was just to satisfy a need for more firearms irregardless of politics.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the M1911 handgun was gradually replaced by Beretta designs imported from Italy.

Starting in the 1970s, Iran phased out WWII-era machine guns (except the M2 .50cal Browning) with the West German-made MG3. This was the Bundeswehr’s Cold War-era version of the Wehrmacht’s WWII MG-42, updated to use 7.62mm NATO ammunition. This process was largely completed by the time of the 1979 revolution.

Iran’s WWII-era firearms 1980-1988

Iran’s main battle rifle at the the time of the 1979 revolution was the G3A6 assault rifle, however thousands of M1 Garands were still in use. Smaller numbers of AK-47s were in use and a few Mausers still lingered.

(A gift shop on the Iraq / Iran border filmed by a French TV news crew riding with the Iraqis on the first day of their 1980 invasion.)

A rifle is the most basic item of a soldier’s kit. Immediately after the Shah’s ouster, it was clear to the new islamic regime that they were going to have a problem. The quantity of assault rifles on hand was enough to equip frontline divisions of the regular peacetime army, but would be insufficient for war. Production of the G3A6 fell to nothing after the revolution and only slowly crept back up after the Iraqi invasion, not reaching the 50,000/annually level until late in the war. Obviously no rifles of any sort would be coming from the USA. The American embargo, while not legally binding internationally, discouraged arms makers in Europe from doing business with Tehran.

(Iranian M1 Garand in action during the first battle of Khorramshahr in 1980, which Iran lost. Iraq occupied Khorramshahr between late 1980 to mid-1982, when Iran liberated it in the second battle of Khorramshahr. Between the two engagements and air raids inbetween, the city was flattened.)

(M1 Garand being used in house-to-house fighting in Khorramshahr in 1980.)

(The Iranian soldier in the cap has a M-1310 Mauser, while his comrade in the M1 steel pot has a Soviet-made RPG-7. This photo is from the 10-month siege of Abadan. The grill of a Willys jeep is visible; Iran used both the WWII MB model and the postwar M38 version. Upkeep was aided by an American Motors factory in Iran nationalized after the 1979 revolution.)

(An Iranian child soldier of the Basij with a Kootah carbine during the 1980-1988 war. Iran’s use of child soldiers was scandalous. The bolt-action Kootah was by no means the worst weapon issued to Basij fighters; sometimes they were sent to the front with a cheap civilian ‘Saturday night special’ revolver and a few rounds of ammo.)

In 1979 Iran began importing AK-47 clones from China and North Korea, an effort which gathered steam after the 1980 Iraqi invasion. The Norinco Type 56 (Chinese copy of the AKM) gradually became the standard rifle. Iran began manufacturing it’s own stamped-metal receiver AK variant called the KLF. Finally, to close the gap, the tremendous quantities of Iraqi AK’s captured in battle were reissued.

(An Iranian soldier collects Iraqi assault rifles after a battle. In this case, the one in front is the Hungarian-made AK-63(AMM) variant. Captured Iraqi AK’s helped keep Iran in the fight.)

None the less, the WWII-vintage M1 Garand remained in sporadic Iranian issue throughout the war. There was no pattern of issue, they popped up irregularly on all fronts. Because of the ammunition non-compatibility problem later in the war, it wasn’t unusual to see an Iranian soldier armed with a M1 also carrying a folding-stock AK.

(Iranian soldier with M1 Garand takes cover.)

(Iranian troops with M1 Garands during an islamic indoctrination session during the 1980-1988 war.)

(In this 1980s photo the man on the left has a Kootah carbine, the uniformed Iranian soldiers G3A6 assault rifles, and the man on the right a M1 Garand.)

(The Iranian soldier in the gas mask has a M1 Garand, while his comrades in the M1 steel pots have G3A6s. This was probably later in the war when Iraq began using chemical weapons in earnest.)

(An Iraqi display of captured guns after Iran’s disastrous defeat on the Faw peninsula in April 1988. Any imaginable AK variant is represented along with G3A6s, but the third teepee up on the right has a Kootah carbine showing that some were still in use near the war’s end.)

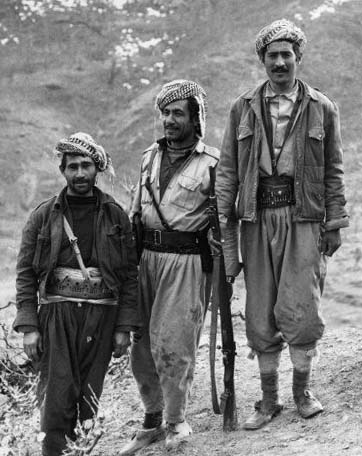

Iran also supplied old WWII weapons, both Garands and Mausers, to Kurdish irregulars. The situation of the Kurds during the 1980-1988 war was quite confusing. The PKK, the main Kurdish group inside Iraq, was adamantly opposed to Saddam Hussein and to a lesser extent, against Iran. Iran provided arms to this group. Meanwhile there were Kurdish militias loyal to the Baghdad government, which were supported by Hussein. Finally there was a small splinter group inside Iran which was violently opposed to the Tehran regime and willing to cooperate with Baghdad. Both sides made use of all these groups.

(Kurdish fighters with a M-1310 Persian Mauser.)

The M2HB .50cal Brownings were used heavily throughout the war. For the most part, they were employed as low-altitude AA guns and as infantry support weapons aboard APCs. The Pasdaran (Revolutionary Guard’s sea corps) used them sometimes to attack helpless civilian ships in the so-called “Tanker War” phase of the conflict, although the Cold War-era ZU-23-2 and DShK were more common in that role.

(Iranian Ma Deuce ready for anti-aircraft work.)

(Iranian M2HB in the infantry-support role.)

(Iranian soldiers atop a M113 Gavin APC during the war’s later stages. The ammo box for the M2HB is still American-marked. The more modern weapon is a BGM-71 TOW anti-tank missile launcher. This Cold War-era missile was lethal to Iraqi tanks throughout the conflict.)

The M1919s were in sporadic use, declining as .30-06 ammunition became less plentiful and the guns themselves captured or destroyed.

(Iranian M1919A4 in action against Iraq.)

The M1911 handguns served throughout the war in declining numbers as they wore out or were lost. For the most part, Iran’s standard pistol was the Cold War-era Beretta 92, with the M1911 a substitute standard. In very limited use were two pistols of WWII design (but not manufacture), the Browning Hi-Power and the Walther PPK. As the war dragged on, increasing use was made of captured Iraqi Tariq semi-autos.

(Iranian APC driver with his M1911A1 sidearm. The vehicle is a Cold War-era BTR-50 of Soviet origin. Both Iran and Iraq used this design during the war. The BTR-50 was amphibious (the two petal doors cover waterjets) and was extremely useful in the Shatt-al-Arab waterway.)

It had just been assumed that the Lugers were long gone by the time of the 1980 Iraqi invasion, however during the post-2003 American occupation of Iraq, one Persian P08 was recovered; obviously an Iraqi capture from the 1980-1988 war. This extremely rare gun was saved for museum donation.

(A US Navy lieutenant with the Persian P08 recovered in Iraq.)

Often forgotten is that while Iran fought an existential fight on it’s western border during the 1980s, it’s eastern neighbor, Afghanistan, was in the midst of it’s own internal conflict involving the USSR. The Khomeini regime supported a group of shiite Afghan mujahideen called the Tehran Eight. Much smaller and weaker than the seven main sunni Afghan mujahideen groups, these eight forces spread around Afghanistan fought the communist government and Soviets, sometimes the sunni mujahideen, and on occasion each other. As Iran desperately needed any full-auto firearm it could get it’s hands on, the M1 Garand was an option to supply these rebels in Afghanistan. Some survived into the Taliban era, for example one ex-Iranian M1 Garand was recovered by American troops in Herat province in 2007.

(Soviet Cpt. Pavel Bekoev of the GRU’s 177th Spetsnaz Detachment in Afghanistan during 1986, with a captured M1 Garand. His comrade has a AK-74 with the rarely-seen PBS1 suppressor.)

There was another mujahideen faction called the “Independent Front” by the USSR (certainly not it’s real name) in Afghanistan’s Nimruz province not aligned with any other faction. In the waning years of the Shah’s reign, it apparently obtained some Mausers and Garands from corrupt Iranian gendarmerie and army units across the border. Little is known of the group as the Soviet 40th Army basically abandoned Nimruz province for most of the conflict.

ARMORED VEHICLES

existing legacy vehicles

The first Iranian combat vehicles were La France TK-6 and Marmon-Herrington armored cars (below) bought from the USA in the 1930s. The latter were fitted with Swedish-made 37mm guns in Iran. These vehicles were already obsolete by WWII and probably were not retained postwar.

Iran’s first tracked armor was the Czechoslovak-made AH-IV tankette, of which 50 were delivered in 1936-1937. This 2-man vehicle weighed just shy of 4 tons and was armed with two vz.26 7.92mm machine guns. It had a Praga RHP gasoline engine and a top speed of 28mph. The armor was extremely thin, no more than ½”. The Iranians loved the nimble little AH-IV and an additional 400 were ordered, however only an additional 50 were delivered before events in Europe intervened. The 100 Iranian AH-IVs were split equally between the 1st and 2nd tank divisions.

Tankettes were a worldwide military fad in the 1930s, when they were predicted to play a big role in any future war. WWII showed the concept to be terribly flawed. When the UK invaded Iran, the Imperial army wisely ordered these little vehicles not to engage the British and all 100 were put into storage. After WWII, they were reactivated and served until 1948-1949.

The first modern Iranian tank was the Skoda TNH of which 100 were ordered in 1935. Only 60 had been delivered by the end of 1937, further fulfillment was cancelled by Czechoslovakia’s futile mobilization in 1938 after the Munich Agreement gave the Sudetenland to Germany.

The 3-man TNH was armed with a Skoda A4 high-velocity 37mm gun with 60 rounds of ammunition, along with two vz.35 7.92mm machine guns. It weighed 9½ tons and was powered by a 6-cylinder Praga gasoline engine. It had leaf-spring suspension. The armor was between 0.30″ to 1¼” thick.

The TNH was a good tank for it’s size and era, roughly equivalent to the Wehrmacht’s Pz. 38(t) of WWII. These tanks served on post-WWII until the Shermans were delivered in 1951. Some were still in storage at the time of the 1979 revolution but obviously they were unsuited for modern use and not reactivated.

the M4 Sherman

The United States supplied 15 M4 Shermans in 1951. Iran did not list any in inventory in 1973, however some were seen during the 1979 revolution and obviously some were used against Iraq between 1980-1988. The Shermans replaced the pre-WWII Czechoslovak-made tanks in Iranian service.

(Iranian Shermans in Tehran.)

The main American tank of WWII, the Sherman weighed 33½ tons. It had a 5-man crew and a top speed of between 25-30mph depending on the engine and suspension package. The armor ranged from 1½”-2″ thick on the hull, and 2″-2½” on the turret with a 3½” mantlet.

(An Iranian Sherman outside a radio station during a failed 1953 coup attempt.)

Despite it’s relatively small inventory Iran used three versions of the Sherman:

The M4 was the basic cast hull design with the Continental R-975 radial gasoline engine, vertical volute suspension package, and M3 75mm gun with 90 rounds of ammunition. It had a coaxial M1919A4 machine gun and another in the front of the hull, operated by the radioman. This model had the early-WWII “split”-style roof hatches.

The M4A3(105) was a later-war welded hull with a M4 105mm howitzer replacing the main gun. A total of 66 howitzer rounds were carried. This was a vehicular-mount version of the M101A1 artillery piece (which Iran also operated) more intended for infantry support than tank combat. There was an anti-tank shell, the M67, also available and typically a few of these were mixed in. The front hull glacis had slightly thicker (2½”) armor. The M4(105) retained the early Continental gasoline engine, however the Iranian tanks of this type had the HVSS suspension package. Because there was no need for a gun stabilizer, these tanks had a second ventilator installed.

(Iranian M4A3(105) Sherman with HVSS suspension. This Iranian tank was captured by Iraq during the 1980-1988 war and in turn captured by the USA during the 2003 invasion. It was missing it’s engine and transmission. It was later moved to Ft. Knox, KY for restoration.) (photo by Michael Green)

The M4A1E4 was the basic M4 but upgraded to the M1 76mm tank gun. As delivered, it had vertical volute suspension but Iran may have upgraded some to the HVSS suspension package. Of this variant, some or all of the Iranian examples had the 16 9/16″ postwar T74 tracks replacing the WWII T54E1 chevron model.

(M4A1E4 Sherman with vertical volute suspension alongside the tank it replaced, a Skoda TNH, today preserved in Tehran.)

Iran considered Shermans inferior to the M36 tank destroyers, however up until the delivery of M47s started, these were the most versatile fighting vehicles in the country’s inventory.

the M36 Jackson

A total of 90 of these WWII tank destroyers, of differing versions, were ordered by Iran in the 1950s. It’s not believed that all ordered were actually delivered. The 5-man M36 weighed 31½ tons and was 24’6″ long including the gun barrel. This vehicle was powered by a Ford GAA-V8 gasoline engine and had a top speed of 26mph.

(A pair of Iranian M36B1 Jacksons, today preserved in a memorial park in Shiraz, Iran.)

During WWII, the USA’s tank destroyer doctrine differed from other countries. As opposed to casemate-style assault guns like the StuG III or SU-100, the M36 was a turreted vehicle largely resembling a tank, but sacrificing some items (like a proper roof or mine protection) in exchange for a larger gun and less-costly production. In the US Army’s thinking, tanks were general-purpose vehicles to support infantry and only duel other tanks as needed; while tank destroyers (organized into special battalions) were specifically to fight tanks and nothing else. In practice this theory was flawed but it barely mattered for the Jackson, as it’s punishing 90mm gun allowed to to often emerge victorious regardless.

The M36’s main gun was a 90mm M3 with 47 rounds. By WWII standards, this was an extremely powerful gun; with the 10½ lb M304 armor-piercing shell having a sizzling 2,700fps muzzle velocity. The theoretical maximum range of 10 miles was of course restricted by how far the gunner could see. The secondary gun was a M2 Browning .50cal on an anti-aircraft pintle. There was no coaxial gun, as per the original doctrine, the M36 shouldn’t fight infantry.

The collar of the gun mantlet was 5″ steel, and the rest of the half-cylinder mount plate was 3″. The sides of the turret were 1¼” rolled steel. Elsewhere, the armor was only 1″ or less. The big bustle on the turret rear was a hollow piece of cast steel, serving both as ammunition storage and a counterweight to the gun barrel.

(This Iranian Jackson had been captured by the Iraqi 8th Division during the 1980-1988 war and was subsequently destroyed during the 2003 American invasion. This photo shows the ammo racks inside the turret rear bustle.)

Iran had two versions of the Jackson. The M36 was the basic design, on the M10 Motor Carriage chassis. The M36B1 was a M36 turret and systems fitted onto a M4A3 Sherman lower hull.

(A standard M36 Jackson, today a gate guard at Dezful army base, Iran. The four-tone ‘splotch’ camouflage shown was used late in the 1980-1988 war, primarily on captured Iraqi Cold War-era tanks.) (photo by Sajjad Shirboti)

The number still in service at the time of the 1979 revolution is uncertain but surely some were. These vehicles were still considered competitive by the Iranians as late as the end of the 1970s.

the M18 Hellcat

Along with the M4 Shermans, Iran received 55 M18 Hellcat tank destroyers in 1951. A WWII product of the Buick car company, this tank destroyer weighed just shy of 20 tons. It had a five-man crew and was 20’10” long including the gun barrel. Powered by a Continental R-975 gasoline engine, it was one of the faster tracked vehicles of WWII with a top speed of 50mph. Part of it’s speed was owed to it’s meager armor, just 1″ and in some place less. The armament was a M1 76mm anti-tank gun with 45 rounds, backed up by a M2 Browning .50cal AA gun in the open-topped turret.

(Imperial Iranian army Hellcats in 1955.)

Despite it’s layout the Hellcat was not a true tank, and was more a mobile anti-tank gun. None the less, when used with the proper tactics, it was very lethal, being the most-credited tank destroyer in the US Army during WWII.

(M18 Hellcat in Tehran.)

Iran’s Hellcats were apparently all out of frontline service before the 1979 revolution although many were warehoused in reserve.

the M24 Chaffee

The USA sold Iran a hundred M24 Chaffees between 1954-1956. This 20-ton tank was 18’3″ long including the gun barrel and armed with a M6 75mm main gun and two M1919A4 .30-06 machine guns. It had a 5-man crew and a top speed of 35mph. During the Korean War, the US Army had judged the WWII-vintage Chaffee insufficient to take on communist T-34s and they were rapidly being disposed of in the mid-1950s. In 1973, all 100 Iranian Chaffees were still listed as “active”, however by most accounts this had fallen to no more than four dozen at the time of the 1979 revolution.

(This Iranian Chaffee was captured by Iraq (which also operated the M24 during the 1980-1988 war) and later destroyed by an American airstrike in 2003.)

the M8 Greyhound

In 1954, Iran ordered a hundred WWII-surplus M8 Greyhound armored cars from the USA. These were drawn from US Army storage and delivered between 1955-1957. Originally a “combat scout vehicle” during WWII, this 6×6 vehicle proved itself very reliable and useful in a number of wartime roles. It was also economical to operate in peacetime. The four-man Greyhound weighed 8½ tons and powered by a Hercules JXD gasoline engine, with a governed top speed of 55mph. It was a 6×6 vehicle with decent off-road mobility. The main armament was a M6 37mm anti-tank gun, along with a coaxial M1919 machine gun and a M2 Browning on an anti-aircraft ring. Despite it’s anti-tank gun, it was not intended to go 1-on-1 vs enemy tanks and it’s main asset was speed, as it’s armor was only ¾” to ½” thick.

The Imperial army had phased out it’s 100 M8 Greyhounds in 1974. However after the 1979 revolution, the islamic army reactivated 32 from storage as further M113 Gavin APCs would obviously never be coming from the USA.

Along with the Greyhounds, Iran received 140 M20 utility cars in the late 1950s. These were simply Greyhounds with no turret and most combat features deleted. A few of them were reactivated in 1979 as well.

Replacement of WWII-era armor

In 1958, the first of many hundreds of M47 / M48 Patton tanks were delivered, followed by modern M60s starting in 1970. From Great Britain, 707 Chieftain Mk.III tanks were delivered between 1971-1975. These Cold War-era tanks formed the nucleus of the Iranian army at the time of the 1979 revolution. Had it not been for the Shah’s ouster, all WWII-era armor would have been completely out of Iranian use by the early 1980s.

Iran’s WWII-era tanks 1980-1988

Iran’s dwindling numbers of WWII-vintage armor was among the first units exposed to the Iraqi invasion. Most of Iran’s M4 Shermans and many of the remaining M24 Chaffees were assigned to the 151st Fortifications Battalion, an understrength defensive-only mechanized unit with 80 total vehicles. This unit, assigned to defend Khuzestan province, was a hodge-podge of types and eras including the WWII-vintage vehicles, some Korean War-era recoilless rifles, a few M47 Patton tanks, and a very limited number of modern BGM-71 TOW guided anti-tank missile launchers. The 151st was at it’s assigned (albeit undersized) vehicle level, but was short of personnel due to the islamic regime’s purges in 1979. When it became clear that an Iraqi invasion was possible, the battalion prepared as best as it could, moving 1¾ miles away from the Shatt-al-Arab so that the Shermans would have some breathing space from Iraqi anti-tank missiles on the waterway’s west bank. The Iranians assigned the M4 Shermans into two-tank “platoons”, supported by modern APCs and the WWII Chaffees.

(An Iranian Chaffee inside Khorramshahr during the failed 1980 defense of the city.)

(Khorramshahr’s waterfront had been built up with cargo wharfage during the British occupation in WWII. During the 1980-1988 war this was all destroyed. This photo was taken on the day of the initial Iraqi invasion.)

The Iraqis attacked Khuzestan province (the southwestern corner of Iran at the northern end of the Persian Gulf) with their army’s entire 3rd Corps, six divisions in total, and not surprisingly the 151st Fortifications Battalion was completely overrun. Five M4 Shermans were lost along with a M24 Chaffee during the initial attack, later at least one more Chaffee was destroyed inside Khorramshahr during the failed defense of that city in October 1980. By this time the Iranian 92nd Armored Division had mobilized and it’s modern Chieftains relieved the hopelessly outclassed WWII tanks in Khuzestan.

Prior to the Iraqi invasion, the Shermans had modern radios installed eliminating the need for a dedicated radioman. The fifth crewman position was completely deleted, with the bow M1919 machine gun, old radio, and operator’s seat being stripped out. The vacant void was occasionally filled with sandbags to provide a bit of extra protection to the vehicle.

(An Iranian M4A3(105) Sherman which was captured by Iraq in 1980.)

(Another tank of the same type, captured by Iraq during the war. This Sherman was found by American troops after the 2003 invasion.)

(Photographed in 2004, this captured Iranian Sherman was displayed as a monument in Iraq after the 1980-1988 war. After the 2003 American invasion it was moved to Camp Buerhring, Kuwait, for EOD personnel training.)

After the loss of Khorramshahr, the tiny remaining pool of WWII-era armor played no decisive role in the conflict. Some M24 Chaffees were used on the war’s northern front later in the conflict, and reportedly a few of the M4 Shermans were transferred to Iran’s Caspian Sea sector to free up more modern tanks for use on the front. Later one was used at the Iranian Armor Centre training school, which had been established by the USA during the Shah’s reign.

Iraq operated it’s own WWII-vintage armor, namely T-34 tanks, SU-100 tank destroyers, and a handful of it’s own M24 Chaffees. There is no record of Iranian and Iraqi WWII-vintage armor ever engaging one another, which is not to say that it never happened.

There is no record of M18 Hellcats participating in the war. There is some evidence that a few of the M8 Greyhound armored cars took part.

(This Republican Guard-marked M8 Greyhound was found by American troops inside Iraq in 2003. It is hard to say if it was captured Iranian or Iraqi from the start, as both countries operated the Greyhound.)

The M36 Jackson was probably the only WWII-era Iranian armor with any real battlefield relevance during the war. It’s main gun could easily defeat Iraq’s WWII-legacy T-34s. Against Cold War-era Iraqi tanks, the M36 could penetrate the Type 59 and T-54/55 at 1,000 yards and the T-62 at 250 yards. That being said, it’s armor was insufficient against either of the Cold War-era guns those two tanks carried, and likewise was insufficient against the modern HOT and AT-3 “Sagger” anti-tank missiles Iraq used.

(Iranian M36 Jackson from the 1980-1988 war.)

(This captured Iranian M36B1 was discovered in Iraq in 2o03 and initially described as “a M4 Sherman with a PzKw V Panther turret” which of course is not true.)

(The same M36B1 as above. An item of mystery was the shiny cylinder inside the barrel showing inside the muzzle brake. It was suggested that this was maybe an aerated flame tube similar to the Cold War-era M67 flamethrower tank. Other ideas were a subcaliber training device, or a pyrotechnics projector to make the tank “shoot” for Iraqi propaganda. Later it was said that the muzzle brake was damaged and pushed down into the gun. This Jackson was allocated to the Polish contingent as a trophy and no definitive answer was ever given.)

(The same M36B1 arriving in Poland. It was severely gutted inside and only given a cosmetic restoration. The Poles repainted it in WWII US Army markings for museum display.)

(A different pair of M36B1s which had been captured by Iraq. There is evidence the Iraqis tried to make these two operational.)

(A captured Iranian M36, this one was discovered along Iraq’s Hwy 1 near Tikrit after the 2003 American invasion. It was later moved to Camp Speicher, Iraq and then to Ft. Campbell, KY.) (photo by Geoff Walden)

There is anecdotal, but by no means solid, evidence that Iran sourced a handful of additional M4 Shermans on the worldwide black market during the 1980-1988 war. This is not as far-fetched as it maybe sounds, as 35 years after the end of WWII, M4s were not as rare in 1980 as they are today in 2016.

As far as modern tanks, the embargo obviously precluded any further M60s from the USA. Meanwhile a buy of 1,370 British-built tanks called Shir Iran which had been designed and negotiated under the Shah, was cancelled by the UK. This left Iran with few options. Iran imported 150 Ch’onma-ho I tanks (ostensibly an equal to the T-62) from North Korea early in the conflict, followed by massive numbers of Type 59 and Type 69-II tanks from China. These Cold War-era Chinese tanks were also bought by Iraq, as the Chinese had no qualms about equipping both sides.

The Chieftain was a huge disappointment to the Iranians, performing poorly. A large number were captured by Iraq which likewise disliked it. Saddam Hussein donated some of these tanks to Jordan. The best Iranian tank was the M60 which outperformed anything the Iraqis had throughout the conflict, including the T-72. Early in the 1980s, an Iranian M60 crew unhappy with the islamic regime drove across the Soviet border, providing the USSR with a firsthand example of this top-line American tank.

For the most part, Iran’s tank losses were replenished by colossal numbers of captured Iraqi tanks. This was aided by the Iraqi army’s woeful lack of armor recovery skills; in many cases tanks with simple problems like a seized starter or cracked track sprocket were abandoned by their crews. Iran’s captured vehicle program started almost immediately after the initial Iraqi assault. For example, in September 1981, Iran already had enough functional ex-Iraqi armor to equip one battalion with ten tanks and three dozen APCs. The Revolutionary Guard’s 1st Division was by 1982, entirely equipped with ex-Iraqi vehicles, 330 in all, captured in 1980 and 1981.

(A parking lot of Iranian armor captured by Iraq between 1980-1988. Shown are M47, M48, and M60 tanks, three BTR-50 APCs, and a WWII-era M4 Sherman.)

After the 1988 ceasefire any surviving WWII-era tanks (probably not many) were eliminated from the Iranian army’s inventory.

ARTILLERY

existing legacy weapons

After the First World War, the Imperial Iranian army imported some Bofors 75mm mountain guns from Sweden. These were joined by Skoda 105mm field guns imported from Czechoslovakia before WWII.

Both of these weapons remained in use in the post-WWII imperial army, generally being phased out in the 1960s.

the M101A1 105mm

This had been the M2A1 howitzer during WWII, with the designation being changed in 1962. Iran purchased 250 of these artillery pieces in 1960, with deliveries coming between 1961-1964.

The M101A1 artillery piece weighed 2½ tons; and was 19’6 long and 5’8″ tall. It had -5°/+66° elevation and a maximum range of 7 miles. The standard M1 high-explosive 105mm round weighed 42 lbs. There was also a direct-fire M67 anti-tank round with a range of 4 miles, however these were not common and it’s unknown how many (if any) Iran received. There were also incinderiary (M60), smoke (M64), and training (M14) rounds, all of which were provided to Iran.

(Iranian M101A1 shortly after the 1979 revolution.)

Besides the 8,536 which Rock Island Arsenal built during WWII, abbreviated production continued for another eight years with an additional 1,666 being made. This gun was highly successful in WWII and remained the standard American howitzer of it’s size throughout the Korean War and into the Vietnam War.

During WWII, the US Army assigned three 12-gun M2 battalions to each artillery regiment, backed up by a fourth battalion of larger caliber. The Imperial Iranian army initially assigned them as such too, but as the 1980-1988 war against Iraq progressed, Iranian artillery was redistributed in smaller formations and often mixed with various calibers. One characteristic of the M101A1 that the Iranians liked was it’s ability to be moved underslung by CH-46 Chinook helicopters.

(Iranian M101A1 battery.)

During the mid-1970s, Iran imported some modern OTO-Melara 105mm howitzers from Italy. These were intended to complement and eventually replace the M101A1s. However the 1979 revolution precluded any further buys. Hence, the WWII-vintage M101A1 was the standard towed gun of any type in the Shah’s army and remained so during the 1980-1988 war against Iraq. After the embargo started, sourcing additional ammunition on the worldwide black market was not difficult, as the M101A1 had been widely exported in Europe, Latin America, and Asia; with many of the recipient countries either making ammunition or having American-supplied rounds they were looking to get rid of as they aged.

the M114 155mm howitzer

This gun weighed 6½ tons and required a heavy truck to tow. It took a well-trained crew about 5-6 minutes to switch from the towed to firing positions or back again. When positioned, the gun rested on a jacked platform, braced by weighted steel spades on the ends of the carriage’s trails.

The M114’s maximum range was 9 miles. To fire, the shell (usually the M107 HE round) was hand-loaded, hand-rammed in the WWII style, then followed by the propellant bag. The breech was shut, and finally a primer plug was placed into a special hole in the breech. The suggested rate of fire was 1rpm; with a “surge” rate of 4rpm for no mare than 180 seconds.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Iran initially assigned it’s M114s to six-gun batteries controlled at the battalion level. As the 1980s war against Iraq dragged on, this varied. Ammunition was no problem as Iran manufactured M107 shells for the M114 before, during, and after the war.

the M115 203mm howitzer

In 1968, 50 of these heavy guns were delivered from the USA. The massive M115, which had been designated M1 under the old WWII system, weighed 15¾ tons and was 40′ long. The ammunition was separate-type, with a full load of propellant bags the 200 lbs M106 HE shell had a range of 11 miles; with a half-charge it had a range of 6¼ miles. Not surprisingly the recoil was massive and the thick carriage trails had two pairs of spades. A heavy semi-type truck or tracked artillery vehicle was needed to tow the M115.

(Iranian M115 in the 1980s.)

Iran also received at least one of the M43 self-propelled version of this howitzer. This version was very rare, only 48 were ever made.

the M1 mortar

This 81mm weapon was the US Army standard of it’s caliber during WWII and the Korean War. It fired either a light (M43) or heavy (M45) shell out to 3,300 or 2,500 yards respectively. It used the M4 mortar sight which was also provided by the USA.

Replacement of WWII-era artillery

Iran’s other pre-revolution artillery was all Cold War era, notably M107 self-propelled 175mm guns and in the late 1970s, M109 Paladins, both from the USA. During the 1980-1988 war, these were irreplaceable because of the embargo and were supplemented by M-1978 Koksan self-propelled 170mm guns from North Korea, D-20s captured from Iraq, and other miscellaneous types.

Iran’s WWII-era artillery 1980-1988

Unlike the tanks and machine guns, WWII-era artillery was very much still in use in the Iranian army at the time of the 1980 Iraqi invasion.

One reason the WWII-era guns served the whole war was that artillery was critically important to Iranian tactics. The overworked Iranian air force gave excellent ground support when possible, but was already overstretched. Meanwhile the Iranian army’s AH-1 Cobra helicopters were usually used for anti-tank missions, therefore artillery was substituted for tasks which would have otherwise been airstrikes.

(Iranian M101A1 battery setting up during the 1980-1988 war.)

(Iranian M115 in action against the Iraqis.)

(Iranian M115 crew preparing to ram propellant bags during the 1980-1988 war.)

Perhaps the most surprising artillery piece in the 1980s war was the old 75mm mountain guns, now six decades old. Some of these elderly guns had been kept in storage by the gendarmerie, and four were reactivated for use in 1980. Their fate is unknown.

Losses of WWII-era artillery were replaced by Cold War artillery purchased from China and North Korea, or “loaned” by Syria, which itself then received new Soviet-made replacements, thereby allowing an indirect way for Iran to buy artillery from the USSR.

Captured Iraqi artillery also played a critical role. However none of these captured guns were WWII-era, as the Iraqis likewise placed heavy importance on artillery tactics and had thoroughly modernized their inventory prior to the war.

One ex-Iranian M101A1 was displayed in Amara, Iraq for some years after the war. The Iraqis retained some captured WWII-vintage Iranian artillery after the 1988 truce and some of these guns were used during Desert Storm in 1991.

(This M115 had an interesting life. Built by Rock Island Arsenal, it was allocated to the US Army in Europe, then sold to Iran, which after the revolution, used it against Iraq. In turn the Iraqis captured it and used it against Iran, then against the USA during Desert Storm. The Americans captured it in February 1991 and delivered it back to Rock Island Arsenal where it was restored several hundred feet away from where it had been manufactured decades earlier.)

(The detachable rear carriage dolly of the RIA M115.)

(Layers of paint from the gun’s various owners cover the serial number.)

For the most part, whatever WWII-vintage artillery still around in 1988 was gradually retired by Iran around the turn of the millennium. Of note, in 2015 Iran’s Defense Industries Organization (DIO) unveiled a heavily-upgraded M114 called the HM41. There are major changes to the carriage and a new 19’8″-long chromed barrel. DIO states that the HM41 can fire WWII-design American 155mm ammunition, or a new Iranian-made rocket-assisted shell with a range of 18½ miles. The HM41 can be towed or mounted on the bed of a truck.

(The HM41 upgrade of the WWII-era M114.) (photo via FARS news agency)

AIRCRAFT

No WWII-era military aircraft remained in Iranian use at the time of the 1979 revolution.

(A young Mohammad Reza Pahlavi inspects a Hawker Hurricane fighter in 1946. Some were left behind by the departing RAF after WWII and incorporated into the Imperial air force.)

Iran received P-47 Thunderbolts in 1949 and they served into the late 1950s. The Imperial air force received it’s first F-84 jets in 1957 so the photo below was taken after that time. The Thunderbolt was popular with Iranian pilots, although they were keenly looking forward to the propeller/jet changeover in the air force.

(A pair of P-47 Thunderbolts with a F-84 Thunderjet over Tehran. The P-47 was the final WWII-era fighter in Iranian service.)

In 1949, the WWII legend C-47 Skytrain became the standard transport type. A total of 23 C-47 Skytrains were operated by the Imperial air force (an initial 22 and one replacement). The useful WWII transports were tremendously popular. During the 1960s some saw use supporting the U.N. mission in the Congo.

(Imperial Iranian air force C-47 with U.N. supplies for the Congo.) (photo from iiaf.net website)

In 1973, five WWII-veteran C-47s were still in service, now backing up two dozen modern C-130 Hercules transports. The last Skytrain was retired in 1976.

(A CH-46 Chinook transports the final Iranian C-47 to it’s resting place at a museum in 1976. The Skytrain’s control surfaces were temporarily removed and drogue chutes fitted to prevent the plane from singing like a pendulum.)

During the 1980-1988 war, Iran was chronically short of airlift capacity and the old worn-out C-47s would have certainly been useful if they hadn’t already been discarded. Iran’s main heavy transport was the C-130 Hercules, but these were often grounded for want of embargoed spare parts and at certain points in the war, Iran had to use IranAir jetliners to move men around the country.

(At the time of the 1979 revolution, Iran’s air force was one of the most advanced in the world and WWII was a distant memory, unlike the army and navy which were still using WWII-era assets. Above is the main Iranian strength during the 1980-1988 war: the F-5 Tiger, F-4 Phantom II, and F-14 Tomcat, along with their Boeing 707 refueler.)

HELMETS

the M1 steel pot helmet

(Iranian soldier in a M1 steel pot. This is a still from a film clip illustrating the shocking lack of tank skill by the Iraqis during the 1980-1988 war. The Iraqi tank inexplicably drove up only 70 yards away from the Iranian trench then foolishly tried to turn around, exposing it’s treadwheels and weak side armor. A volley of RPG-7s from the Iranians knocked it out.)

From the 1950s onwards this was the standard Iranian headwear. Iran used two versions of this legendary WWII American helmet. Starting in the 1950s, WWII-surplus M1s were imported from the USA and by the 1960s, these were the Imperial army’s standard helmet. At the time of the G3A6 buy in the 1970s, a significant number of West German M62s were imported with the rifles. The M62 was a post-1950s Bundeswehr version of the WWII American design with some minor changes.

(Iranian M66, the post-WWII West German version of the M1.) (photo by Brendon Ellis)

WWII British models

The Imperial Iranian army had inherited some Mk.II Tommy and Mk.III Turtle helmets from the departing British after WWII. These were the standard helmets until the M1 pots arrived in the 1950s and 1960s. A small number were still in service at the time of the 1979 revolution.

Iran’s WWII-era helmets 1980-1988

The old M1s, and especially the M62s, remained the standard helmets of the Iranian army throughout the whole 1980-1988 war. They remained in use for another decade afterwards, gradually being replaced by Iranian kevlar helmets at the turn of the millennium. A limited number are still in use in 2016.

(M62 helmet still in Iranian use in 2013.)

Some of the old British helmets popped up from time to time during the 1980-1988 war.

(Iranian soldier with a WWII-era Mk.III Turtle helmet during the 1980-1988 war.)

Like everything else, the Iranians also made use of captured Iraqi helmets after 1980. Most of Iraq’s helmets were Cold War-era Soviet and Polish designs, but the Iraqis had limited numbers of WWII-era Mk.II Tommys themselves, in addition to the WWII Soviet SSh-40. As the war against Iran dragged on, Iraq began importing a helmet called the M-80, which was a South Korean clone of the steel M1 made out of plastic-coated fiberglass. Obviously this offered much less protection than a metal helmet but it was far cheaper, and Saddam Hussein was willing to sacrifice cranial health of his troops if it freed up money for other weapons. For the Iranians, captured M-80s had the advantage of blending in visually with the M1 and M62.

(Iranian child soldier of the Basij wearing a captured Iraqi M-80, covered by martyrdon headband.)

(The Qaws an-Nasr, or Hands of Victory, monument in Baghdad opened in 1989. They are two pairs of hands (cast on Saddam Hussein’s own) holding gigantic swords; one pair on each end of a parade ground. At the base of each arm is a net spilling out helmets said to be from dead Iranian soldiers; 5,000 helmets in all. The helmets are a virtual inventory of Iranian WWII types from the 1980-1988 war: Mk.II Tommys, Mk.III Turtles, M1 steel pots, and the postwar M62 version, along with some Soviet-made types presumably captured by Iran. Each helmet has a hole, at the time said to be the shot that felled it’s Iranian wearer, but now known to have been hand-drilled for rain drainage.)

(Some observers noted that WWII British types, especially the Mk.II Tommy, appear in the monument in greater proportion than they were seen in actual Iranian use during the 1980-1988 war. It’s possible that Iraq captured a warehouse full early in the conflict. It’s also not beyond reason that construction was sped up by using Iraqi Mk.IIs as a substitute, as Iraq also used that helmet and was phasing it out in the 1980s. The monument was vandalized during the post-2003 American occupation and many helmets were taken as souvenirs. In 2007, the new Iraqi government began demolition of the hands, only to stop shortly thereafter, and in 2011 restoration work began. The helmets were removed to make the monument less ghoulish.)

Above is a famous photo of the Iran-Iraq War, an Iranian soldier with WWII M1 pot helmet during an Iraqi chemical weapons attack. The machine gun is a MG3, the postwar West German 7.62 NATO version of the WWII MG-42. The gas mask is an American M17, the US Army type during the Vietnam War era. The beige web belt suspenders are Israeli. The Shah stressed that Iranians were ethnic Persian, not Arab, and the Arab-Israeli dispute was not Iran’s problem. Many Iranians disagreed but in any case, Iran and Israel had robust trade in the 1970s, including Uzi guns. All of that ended with the Shah’s ouster in 1979. Khomeini was extremely anti-Israeli, as is the current Iranian leadership. None the less, the Iranians couldn’t afford to discard Israeli-made gear during the war against Iraq. The above photo was possibly taken during the second battle of al-Faw.

Iraq’s Faw peninsula extends into the Persian Gulf with the mouth of the Shatt-al-Arab waterway on one side and the Iraqi navy’s GHQ at Umm Qasr on the other. In February 1986, Iran launched operation “Dawn 8”, an amphibious assault across the waterway which captured the peninsula. One of the most major Iranian victories of the war, occupation of the peninsula bottled up the Iraqi navy and put Basra in danger. If the Iranians were to capture Basra, Iraq would have lost not only it’s second-largest city, but also have become fully land-locked plus lose it’s highway and railroad connection to Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. At the town of al-Faw was an Iraqi coastal defense missile base which the Iranians turned around and used against shipping bound for Kuwait, at that time an Iraqi ally.

Several times Iran tried to capture Basra. At one point they were within eyesight of the city but never succeeded. None the less, continued occupation of the peninsula was a handicap to Iraq.

On 17 April 1988, Iraq launched a massive offensive to liberate the peninsula, notable for two things. It was very well-planned and executed, a rarity for the Iraqi army’s tactics. But more famously, it involved a massive chemical weapons attack, the largest use of gas warfare since 1918. The Iraqis meticulously selected combinations of persistent and non-persistent mustard gas and nerve gas, delivered by missiles and jet aircraft. This both caused immediate casualties and cut off escape routes. After the chemical attack, Republican Guard tank units attacked the gassed Iranians on the peninsula, a mixture of regular army and ill-trained Basij forces. Iraqi MiGs took out the pontoon bridges the Iranians needed to resupply the Faw garrison.

The battle lasted only 48 hours and was a complete Iraqi victory. The Iranian Basij forces, some of which were still using WWII-era M1 Garands and Persian Mausers eight years into the war, were annihilated. For perspective, the Basij had more KIA in a 24 hour span than the USA had in the whole Revolutionary War. Iraq followed up with operation “Forty Stars”, another chemical weapons-laden offensive on the war’s central front which pushed the front lines back into Iran. Both offensives were timed with “Scud” missile blitzes against Tehran.

Khomeini probably cared less about his appalling personnel losses, but the al-Faw counteroffensive was one of the two “shocks” that led him to end the war. Iran lost a huge quantity of rifles, ammunition, and especially army trucks in the battle and more importantly, it was now clear that Saddam Hussein was keen to use chemical weapons heavily, openly, and often. The other “shock” was the accidental shootdown of an Iranian airliner by a US Navy cruiser several weeks later that led the paranoid Ayatollah to believe that conflict with the USA was imminent. The war ended on 20 August 1988. The terms of the truce were a complete return to the prewar status quo; neither side gained anything at all.

LEGACY

With the exceptions noted above, both Iran and Iraq phased out remaining WWII-era weaponry after the 1988 truce. Both sides emerged militarily stronger than they started, but with new problems, in Iraq’s case massive financial debt and in Iran’s case colossal infrastructure damage.

(A pile of M-1310 Persian Mausers mixed with civilian shotguns at a US Army CAHA (captured ammunition holding area) in Iraq during the post-2003 American occupation. These had been captured during the 1980-1988 war, warehoused and forgotten about, then looted in the chaos as Saddam Hussein’s regime collapsed.)

After 1988 the two countries paths diverged. Iraq’s military power was crippled during Desert Storm in 1991, caused by it’s 1990 conquest of Kuwait which in turn had been caused by Iraq’s gross inability to ever pay off it’s war debt to Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the other Arab sheikdoms. What remained of the Iraqi military was destroyed in 2003. Meanwhile Iran gradually repaired it’s war damage and continues to expand and modernize it’s military.

(Iranian M36 Jackson made into a war memorial at Taft, Iran.) (photo by Brian McMorrow)

(WWII-vintage M4 Sherman serving as a monument on an Iranian military base in 2015.)

(The shiite tradition of islam calls for the cleric to have a weapon at hand when preaching. After the end of the 1980-1988 war, the Iranian military donated many of the surviving Persian Mausers to the state-funded imam program for this purpose.)