Month: December 2023

British Bulldog Revolvers

In an effort to outdo Smith & Wesson’s fast-loading, top-break revolvers, Colt brought a solid-frame, swing-out-cylinder revolver to the market in 1889. Its initial models were large-frame handguns in .38 and .41 calibers designed for military use. The success of those models led to Colt’s introduction of smaller-scaled double-actions for the law-enforcement and civilian markets.

The Colt New Pocket, a six-shot revolver offered in various .32-cal. cartridges, was introduced in 1893. Three years later, the New Police was introduced, which married the New Pocket frame with a larger grip for law-enforcement duty. It was promptly adopted by the New York City Police Dept. at the urging of then-police commissioner Theodore Roosevelt.

The New Pocket was replaced by the Pocket Positive in 1905. This model got its name from the “Positive Lock” mechanism patented by Colt in 1905 that prevented the revolver from firing unless the trigger was pulled. Likewise, the New Police adopted the same mechanism and added the option of .38 New Police or .38 S&W chamberings to become the Police Positive. Along with Colt’s large-frame Official Police, the Police Positive would go on to be a popular law-enforcement sidearm, and just more than 1,000 were supplied to the British during World War II.

The New Pocket was replaced by the Pocket Positive in 1905. This model got its name from the “Positive Lock” mechanism patented by Colt in 1905 that prevented the revolver from firing unless the trigger was pulled. Likewise, the New Police adopted the same mechanism and added the option of .38 New Police or .38 S&W chamberings to become the Police Positive. Along with Colt’s large-frame Official Police, the Police Positive would go on to be a popular law-enforcement sidearm, and just more than 1,000 were supplied to the British during World War II.

As with the New Police, a target version of the Police Positive was made. It featured a 6″ barrel and an adjustable rear sight with the topstrap of the frame matted to reduce glare. The trigger and backstrap were checkered. In addition to the .32 cartridges offered in the Police Positive, the Target model was also available chambered in .22 Long Rifle and .22 WRF. In 1923, hard rubber stocks were replaced by checkered walnut, and the cylinder’s chambers were recessed after 1934. A nickel finish was offered on both the standard and target models.

Like the Police Positive, the Target model was made in two versions. The First Issue was made from 1905 through 1925. The Second Issue began in 1926 and had a slightly heavier frame that increased the overall weight of the revolver by about 4 ozs.

The Police Positive Target would serve as a small-frame companion to Colt’s large-frame Officers Model Target. According to Colt’s marketing literature, it was “a fine arm and made to meet the demand for a light, small caliber Target Revolver—medium in price—for both indoor and outdoor shooting; light, smooth pull, well balanced, with the full Colt Grip.” The combination of an affordable price and manageable size meant that the Police Positive Target was more likely to be found on the belt of an outdoorsman than on the competition range. Consequently, many will be found, like the example pictured, with holster wear.

While production of the standard Police Positive would continue until 1947, the last Police Positive Target models were made in 1941. About 28,000 were produced over its production run. The legacy of Colt’s solid-frame, swing-out cylinder, double-action revolvers, like the Police Positive, lives on in the company’s current Anaconda, Python and Cobra models.

The Police Positive Target pictured is a Second Issue model manufactured in late 1930. It is in NRA Good Condition and is valued at $650.

Like the Police Positive, Target models will be encountered with British proofs. Target models in one of the .32-cal. chamberings will bring about a 40 percent premium compared to the rimfire versions.

Gun: Colt Police Positive Target

Manufacturer: Colt’s Mfg. Co.

Chambering: .22 Long Rifle

Manufactured: 1930

Condition: NRA Good (Modern Gun Standards)

And yes my family did NOT ride for Mr. Lincoln! Grumpy

And yes my family did NOT ride for Mr. Lincoln! Grumpy

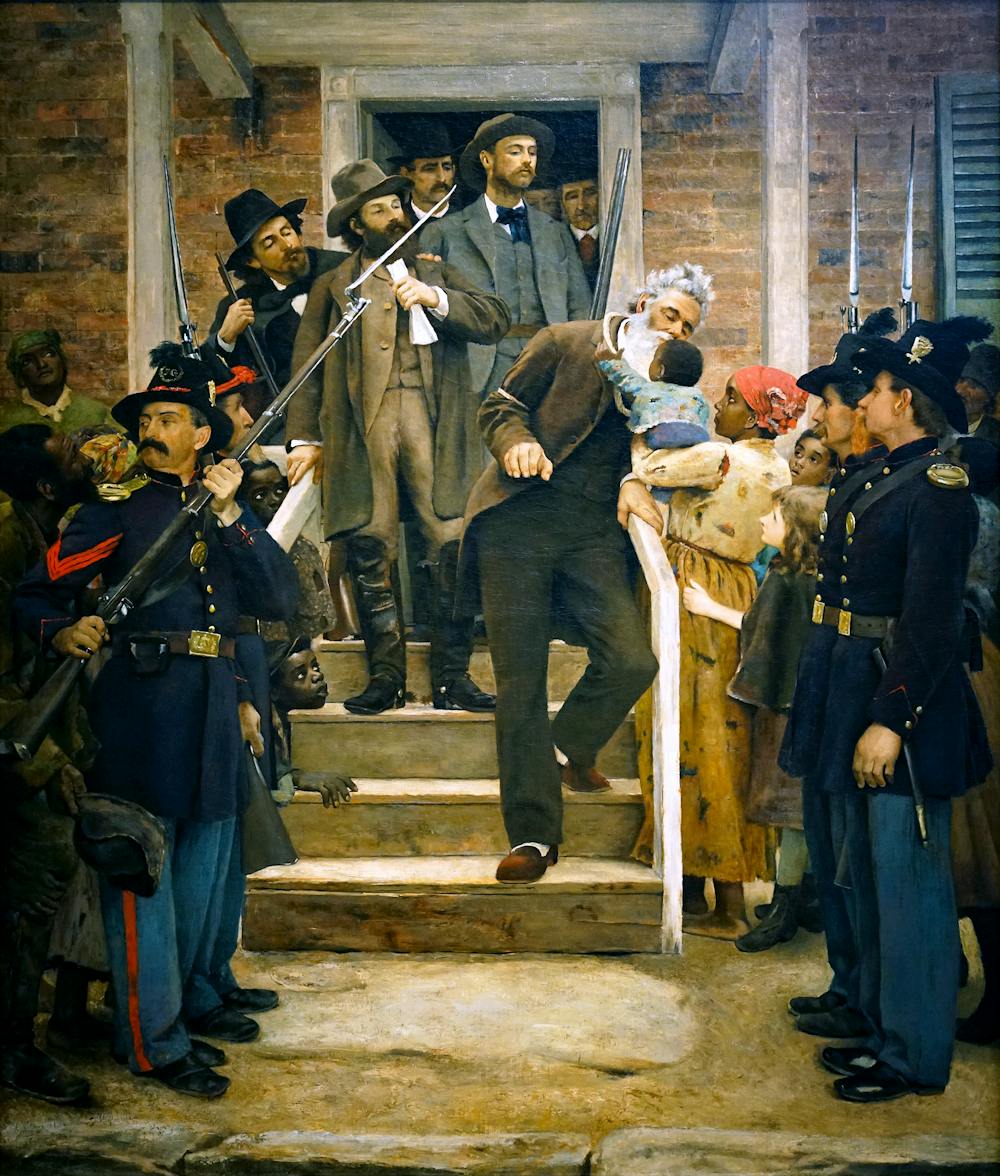

*The Pottawatomie massacre occurred on the night of May 24–25, 1856, in the Kansas Territory. In reaction to the sacking of Lawrence by pro-slavery forces on May 21, and the telegraphed news of the severe attack on May 22 on Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, for speaking out against slavery in Kansas (“The Crime Against Kansas”), John Brown and a band of abolitionist settlers—some of them members of the Pottawatomie Rifles—made a violent reply. Just north of Pottawatomie Creek, in Franklin County, they killed five pro-slavery settlers, in front of their families. This soon became the most famous of the many violent episodes of the “Bleeding Kansas” period, during which a state-level civil war in the Kansas Territory was described as a “tragic prelude” to the American Civil War which soon followed. “Bleeding Kansas” involved conflicts between pro- and anti-slavery settlers over whether the Kansas Territory would enter the Union as a slave state or a free state. It is also John Brown’s most questionable act, both to his friends and his enemies. In the words of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, it was “a terrible remedy for a terrible malady.”[1]: 371

Background[edit]

John Brown was particularly affected by the sacking of Lawrence, in which the Douglas County Sheriff Samuel Jones on May 21st led a posse that destroyed the presses and type of the Kansas Free State and the Herald of Freedom, Kansas’s two abolitionist newspapers, the fortified Free State Hotel, and the house of Charles Robinson. He was the free-state militia commander-in-chief and leader of the “free state” government, established in opposition to the “bogus” pro-slavery territorial government, based in Lecompton.

A Douglas County grand jury had ordered the attack because the hotel “had been used as a fortress” and an “arsenal” the previous winter, and the “seditious” newspapers were indicted because “they had urged the people to resist the enactments passed” by the territorial governor.[2] The violence against abolitionists was accompanied by celebrations in the pro-slavery press, with writers such as Dr. John H Stringfellow of the Squatter Sovereign proclaiming that pro-slavery forces “are determined to repel this Northern invasion and make Kansas a Slave State; though our rivers should be covered with the blood of their victims and the carcasses of the Abolitionists should be so numerous in the territory as to breed disease and sickness, we will not be deterred from our purpose.”[3]: 162

Brown was outraged by both the violence of pro-slavery forces and by what he saw as a weak and cowardly response by the anti-slavery partisans and the Free State settlers, whom he described as “cowards, or worse”.[3]: 163–166 In addition, two days before this massacre, Brown learned about the caning of abolitionist Charles Sumner by the pro-slavery Preston Brooks on the floor of Congress.[4][5][full citation needed]

Attack[edit]

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2013)

|

A Free State company under the command of John Brown Jr. set out, and the Osawatomie company joined them. On the morning of May 22, 1856, they heard of the sack of Lawrence and the arrest of Deitzler, Brown, and Jenkins. However, they continued their march toward Lawrence, not knowing whether their assistance might still be needed, and encamped that night near the Ottawa Creek. They remained in the vicinity until the afternoon of May 23, at which time they decided to return home.

On May 23, John Sr. selected a party to go with him on a private expedition. John Jr. objected to their leaving his company, but seeing that his father was obdurate, acquiesced, telling him to “do nothing rash.” The company consisted of John Brown, four of his sons—Frederick, Owen, Salmon, and Oliver—Thomas Wiener, and James Townsley (who claimed later that he had been forced by Brown to participate in the incident), whom John had induced to carry the party in his wagon to their proposed field of operations.

Letter of Mahala Doyle to John Brown, when he was in jail awaiting execution, November 20, 1859: “Altho vengence is not mine, I confess, that I do feel gratified to hear that you ware stopt in your fiendish career at Harper’s Ferry, with the loss of your two sons, you can now appreciate my distress, in Kansas, when you then and there entered my house at midnight and arrested my husband and two boys and took them out of the yard and in cold blood shot them dead in my hearing, you cant say you done it to free our slaves, we had none and never expected to own one, but has only made me a poor disconsolate widow with helpless children while I feel for your folly. I do hope & trust that you will meet your just reward. O how it pained my Heart to hear the dying groans of my Husband and children if this scrawl give you any consolation you are welcome to it.

NB [postscript] my son John Doyle whose life I begged of (you) is now grown up and is very desirous to be at Charleston [Charles Town] on the day of your execution would certainly be there if his means would permit it, that he might adjust the rope around your neck if Gov. Wise would permit it.”[6]

They encamped that night between two deep ravines on the edge of the timber, some distance to the right of the main traveled road. There they remained unobserved until the following evening of May 24. Some time after dark, the party left their place of hiding and proceeded on their “secret expedition”. Late in the evening, they called at the house of James P. Doyle and ordered him and his two adult sons, William and Drury, to go with them as prisoners. (Doyle’s 16-year-old son, John, who was not a member of the pro-slavery Law and Order Party, was spared after his mother pleaded for his life.) The three men were escorted by their captors out into the darkness, where Owen Brown and his brother Frederick killed them with broadswords. John Brown Sr. did not participate in the stabbing but fired a shot into the head of the fallen James Doyle to ensure he was dead.

Brown and his band then went to the house of Allen Wilkinson and ordered him out. He was slashed and stabbed to death by Henry Thompson and Theodore Wiener, possibly with help from Brown’s sons.[3]: 172–173 From there, they crossed the Pottawatomie, and some time after midnight, forced their way into the cabin of James Harris at swordpoint. Harris had three house guests: John S. Wightman, Jerome Glanville, and William Sherman, the brother of Henry Sherman (“Dutch Henry”), a militant pro-slavery activist. Glanville and Harris were taken outside for interrogation and asked whether they had threatened Free State settlers, aided Border Ruffians from Missouri, or participated in the sack of Lawrence. Satisfied with their answers, Brown’s men let Glanville and Harris return to the cabin. William Sherman, however, was led to the edge of the creek and hacked to death with swords by Wiener, Thompson, and Brown’s sons.[3]: 177

Having learned at Harris’s cabin that “Dutch Henry”, their main target in the expedition, was away from home on the prairie, they ended the expedition and returned to the ravine where they had previously encamped. They rejoined the Osawatomie company on the night of May 25.[3][page needed]

In the two years prior to the massacre, there had been eight killings in Kansas Territory attributable to slavery politics, and none in the vicinity of the massacre. Brown killed five in a single night, and the massacre was the match to the powder keg that precipitated the bloodiest period in “Bleeding Kansas” history, a three-month period of retaliatory raids and battles in which 29 people died.[7]

Men killed during the massacre[edit]

- James Doyle and his sons William and Drury

- Allen Wilkinson

- William Sherman

Impact[edit]

The Potawattomie massacre was called by William G. Cutler, author of the History of the State of Kansas (1883), the “crowning horror” of the whole Bleeding Kansas period. “The news of the horrid affair spread rapidly over the Territory, carrying with it a thrill of horror, such as the people, used as they had become to deeds of murder, had not felt before. …The news of the event had a deeper significance than appeared in the abstract atrocity of the act itself. …It meant that the policy of extermination or abject submission, so blatantly promulgated by the Pro-slavery press, and proclaimed by Pro-slavery speakers, had been adopted by their enemies, and was about to be enforced with appalling earnestness. It meant that there was a power opposed to the Pro-slavery aggressors, as cruel and unrelenting as themselves. It meant henceforth, swift retaliation—robbery for robbery—murder for murder— that “he who taketh the sword shall perish by the sword.”[8]

Kansas Senator John James Ingalls in 1884 quoted with approval the judgment of a Free State settler: “He was the only man who comprehended the situation, and saw the absolute necessity for some such blow, and had the nerve to strike it.” This a result of the men killed being leaders in a conspiracy to “drive out, bum and kill; and that Potawatomie Creek was to be cleared of every man, woman and child who was for Kansas being a free State.”[9]

According to Brown’s son Salmon, who participated, it was “the grandest thing that was ever done in Kansas”

Just Saying