So, don’t think you can do what you are not trained for? Think a beat up old ship can’t be put in harm’s way? Can you really think “out of the box?” Can a ship run aground, over and over, and still get an award? How about a Presidential Unit Citation? How about a destroyer that captures an airfield?

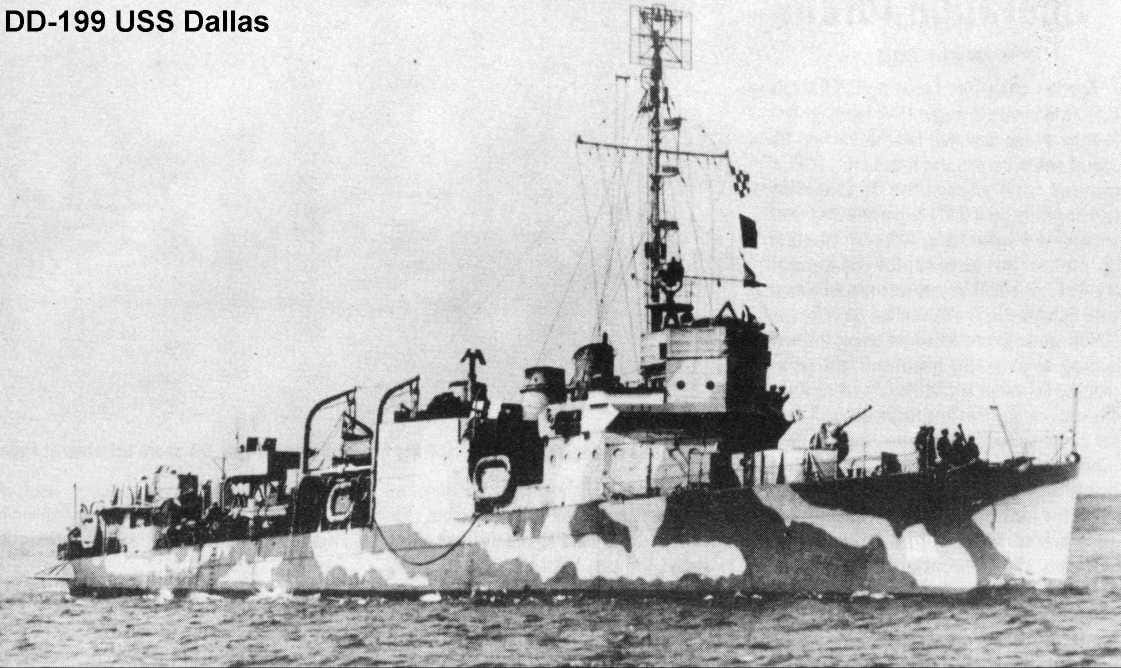

USS Dallas (DD-199), tell us all about it.

On 25 October she cleared Norfolk to rendezvous with TP 34 bound for the invasion landings on North Africa. Dallas was to carry a U.S. Army Raider battalion, and land them up the narrow, shallow, obstructed river to take a strategic airport near Port Lyautey, French Morocco.

On 10 November she began her run up the Oued Sebou under the masterful guidance of Rene Malavergne, a civilian pilot who was to be the first foreign civilian to receive the Navy Cross. Under fire by cannon and small arms during the entire run, she plowed her way through mud and shallow water, narrowly missing the many sunken ships and other obstructions, and sliced through a cable crossing the river, to land her troops safely just off the airport.

Her brilliant success in completing this mission with its many unexpected complications won her the Presidential Unit Citation.

That is the airfield on the right. Oh, and they fought the French the whole way.

On the night of 9-10 November a tactical innovation involving the Navy raised American spirits. On the Sebou River the destroyer-transport Dallas pushed aside a barricade and sneaked upstream with a raider detachment to spearhead the assault on the airfield. As the night wore on, some colonial units gave up the fight, but Foreign Legion units continued to resist. Several companies of the 1st and 3d Battalion Landing Teams made progress, though slow, toward the airfield.

In bypassing a French machine-gun position, three companies of the 1st Team became disoriented and unintentionally provided some comic relief to a difficult night. At 0430 the companies reached a building they thought housed the airfield garrison. Intent on maintaining surprise, the troops crept up to doors and windows, weapons at the ready. Bursting in, the embarrassed Americans discovered they had captured a French cafe. Some 75 patrons put down wine glasses and surrendered. Patrols rounded up about 100 more prisoners in the area.

At daylight on 10 November the 1st Team mounted a new drive, this time with tanks, and by 1045 reached the west side of the airfield. On the river the Dallas passed a gauntlet of artillery fire and debarked the raiders on the east side of the airfield. American troops now occupied three sides of their objective.

Serious opposition still came from the Mehdia fortress. Although naval gunfire had silenced the larger batteries earlier, machine-gun and rifle fire continued. Navy dive bombers were called in, and after only one bombing run the garrison quit. After claiming the fort and gathering prisoners, the 2d Battalion Landing Team moved on to close the ring around the airport. By nightfall the American victory was assured’ and the local French commander requested a parlay with General Truscott. At 0400 on 11 November a cease-fire went into effect, the terms of which brought all GOALPOST objectives under American control.

Yes Virginia, we had to fight against the French before we would fight with them in WWII. One other thing, when looking up the Dallas, I noticed one of her then Junior Officers on that day who is buried at Arlington, Randall T. Boyd, Jr., CDR USN. Just for reference – what a career and life he had.

Commander Boyd saw combat as a naval artillery officer during World War II and as a pilot during the Korean War. He was awarded a Silver Star for his exploits during World War II and the Distinguished Flying Cross for his activities during the Korean War.

Born in Hingham, Massachusetts, and raised in Weymouth, he graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1941. He also earned a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

On November 10, 1942, he was artillery officer aboard the destroyer Dallas when it made a treacherous 10-mile run up the Sebou River to land an Army Ranger detachment to capture Port Lyautey Airport during the assault and occupation of French Morocco.

According to the citation for the Silver Star he was awarded for the engagement, he displayed “remarkable courage under heavy hostile fire during the perilous journey” and “played a large part in providing protective gunfire for our Army Ranger troops and controlled and directed the fire of the ship so efficiently that hostile shore batteries were silenced before they were able to inflict any damage on the Dallas.”

After World War II, he trained as a pilot in Pensacola, Florida, then served in the Korean War.

The first citation for his Flying Cross described him as “a skilled airman and cool leader in the face of hostile opposition.”

According to the citation, he was flying a mission over Korea on October 12, 1950, “when enemy shore batteries attacked US mine sweepers with intense fire.

“Commander Boyd spotted hostile targets, took them under fire and held them down while the vessels escaped from the area. Braving heavy fire sent up from the ground, he controlled naval gunfire and vectored carrier-based aircraft to the enemy positions.”

After the Korean War, he was commanding officer of Naval Patrol Squadron 34, and later was second in command at the Naval Base in Rota, Spain.

After retiring from the Navy, he was an engineer at MIT’s Draper Laboratory, where he worked on the Gemini and Apollo space programs, and a senior engineer at Brown and Root Inc. in Houston, where he oversaw shipbuilding projects.

Ship and man. Benchmark both.

UPDATE: BTW – here is a modern day pic of the river they took that DD up at night. Ballsy? Yep.