Sioux and Cheyenne warriors who gathered west of Fort Phil Kearny on the morning of Aug. 2, 1867, had several reasons to feel confident as they prepared to attack civilian woodcutters and the U.S. Army troops assigned to protect them.

Nine months earlier, Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors had attacked troops along the Bozeman Trail about four miles north of the fort, which is located near present-day Story, Wyo, on the east flank of the Bighorn Mountains halfway between the present towns of Buffalo and Sheridan. Tribal leaders sent out a small band of decoys that managed to lure Capt. William J. Fetterman into an area where he and all 80 of his men were ambushed and killed. At the time, it was the worst military defeat ever suffered by the Army on the Great Plains.

Red Cloud’s War

In the summer of 1867, looking to repeat their success, Indians—furious that white men the year before had built three forts along the new Bozeman Trail across their land in the Powder River Basin—planned attacks on two of the forts. The federal government contended the forts and defense of the trail were necessary because the route offered the quickest path to gold mine discoveries in Montana. The conflict became known as Red Cloud’s War.

Sioux Chief Red Cloud had vowed to kill every white man found on the Indians’ land. The Indians harassed troops and white travelers more or less continually. The next large attacks after the Fetterman massacre came in August.

One contingent of warriors battled soldiers and civilians at the Hayfield Fight on Aug. 1, 1867, near Fort C.F. Smith on the Bighorn River in southern Montana Territory. Early the next morning, Red Cloud and more than 1,000 warriors gathered and attacked woodcutters and soldiers near a spot about six miles northwest of Fort Phil Kearny.

What happened over the course of six hours on August 2 became known as the Wagon Box Fight, a relatively small battle that became well known for several disparate reasons. It was the Army’s first chance to claim victory after the Fetterman disaster, though in retrospect the fight seems more like a draw. At the time and since, there were widely conflicting reports on the number of Indian casualties, and for this reason too the fight continues to draw the interest of students of the Indian Wars.

Finally, the fight is important in the history of tactics because it was the first time a large force of mounted tribesmen faced sustained fire from relatively rapid-shooting, breech-loading rifles. The warriors’ old tactics of closing fast on horseback for close combat with their enemies no longer worked—and they paid a heavy price.

The wood supply

Hundreds of infantry and cavalry soldiers based at Fort Phil Kearny needed a steady supply of wood from forests on the slopes of the Bighorn Mountains for construction at the fort, as well as a constant supply for fuel for cooking and for the next winter’s heating.

Protecting the contracted civilian woodcutters was thus one of the Army’s most important jobs if the troops were to survive in hostile country. The wood line where the prairie met the mountain forest was about six miles from the fort. Wagon trains of woodcutters and their soldier guards suffered constant small attacks during the entire two years Fort Phil Kearny was in existence.

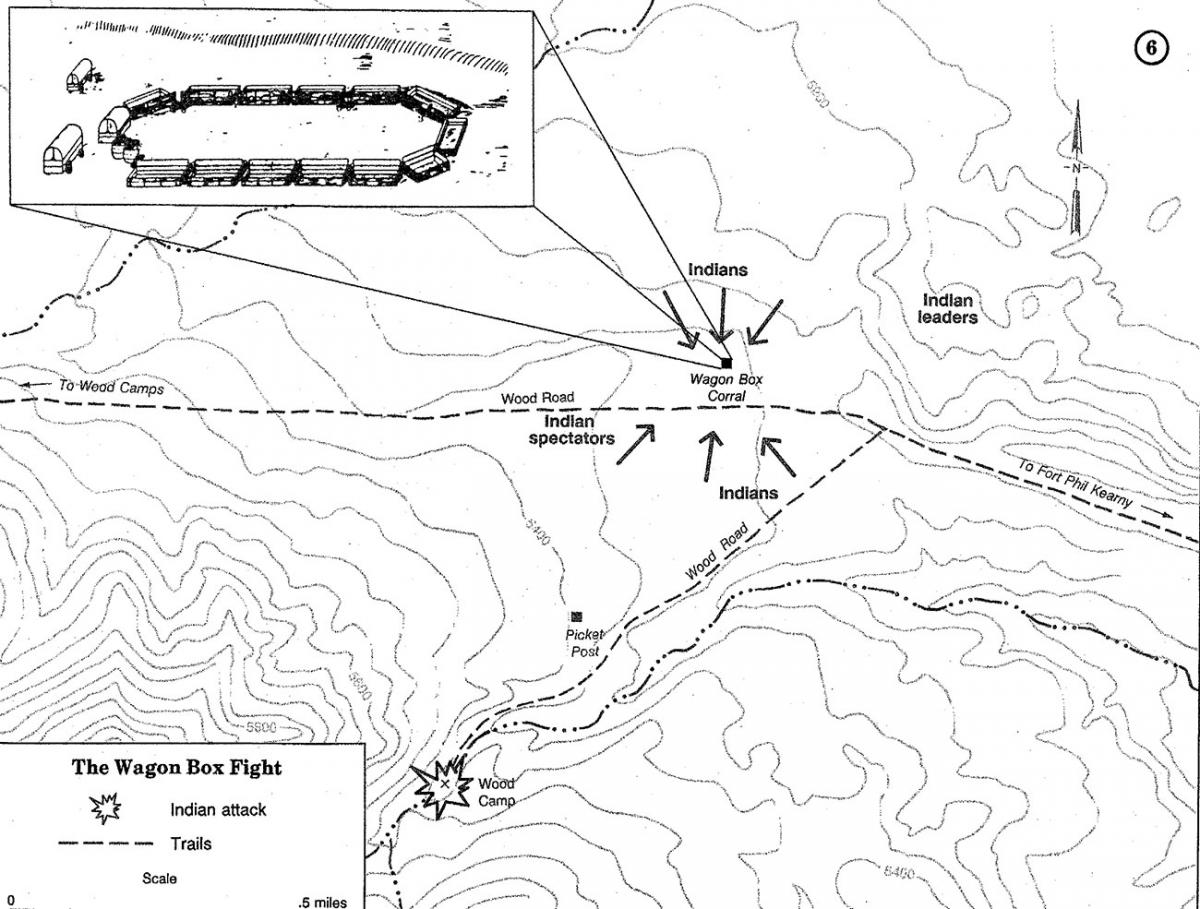

On August 2, the tribes tried something much larger. The Indians held a distinct advantage because their foes had split into two groups. Civilian woodcutters decided to stay at a camp near the wood line, about a mile from a makeshift stock corral the soldiers had fashioned from14 wagon boxes, removed from their running gear and set on the ground. Logs were transported from the woodcutting camp to the fort resting directly on the running gear.

A wagon-box corral

The wagon boxes were 10 feet long, two and a half feet high and four and a half feet wide. The wood was only about an inch thick, with no lining. The boxes eventually served as the main line of defense against a massed Indian force determined to overrun the corral and the 32 men using it as cover.

Capt. James W. Powell was in command of C Company, 26th Infantry, which at the end of July had relieved the company previously guarding the woodcutters, and so his troops were new to the job. He set up operations at the corral.

Early on August 2, Powell sent 13 men out from the corral to guard the woodcutters’ camp and another 14 to escort wagons carrying wood to and from the fort. That left the captain and Lt. John C. Jenness at the corral with 26 enlisted men.

The soldiers at the corral were joined by two civilian teamsters who had left the fort that morning to hunt deer. The pair saw Indian smoke signals and tried to get back to the fort, but wound up at the corral instead.

The first attack

The Indians set their sights on the camp’s mule herd, with 200 warriors on foot trying to scatter the animals, but the mule herders kept the attackers at bay until a new wave of Indians managed to drive off the herd and set fire to the woodcutters’ camp. Simultaneously, about 500 Indians attacked the woodcutters. Then the woodcutters and their soldier guards tried to move toward the fort, bypassing the corral.

Three soldiers and four civilian contractors were killed, but Powell managed to divert the Indians’ attention by mounting an attack on the rear of the Indian force from the corral, which allowed the rest of the woodcutting camp’s occupants to hide in the timber or get to the fort. Within 15 minutes, an estimated 800 Indians on horseback surrounded Powell and his men at the makeshift corral.

Using field glasses to scan the area, Lt. Jenness reportedly told the men he spotted Red Cloud at the top of a hill with other Indian leaders. It has never been verified that Red Cloud was at the scene, and because the lieutenant didn’t know what the man looked like, Jenness may have misidentified another chief.

Trapdoor Springfields

Unlike Fetterman’s troops, who carried muzzle-loaders that could only fire three rounds a minute at most, the men at the wagon boxes were equipped with new breech-loading Springfield trapdoor rifles. Seven hundred of these weapons were brought to the fort a short time before by wood contractor J.R. Porter of the Gilmore & Proctor firm. They could fire 15 to 20 rounds per minute. Unfortunately, there hadn’t been any time for target shooting, and Army weapons training was known to be dubious at best. Still, most of the men managed to at least become familiar with the new rifles in the weeks since the weapons had arrived.

The soldiers punched two-inch holes into the wooden wagon boxes so they could fire through them. Yokes, bags of grain, kegs and other equipment were stacked between wagons for protection. Some men fired over the tops of the boxes, and blankets covered the tops to hide the men’s positions and provide limited protection from the arrows raining down on them.

The Indians were primarily armed with bows and arrows, lances and war clubs, though some had firearms captured months earlier during the Fetterman attack. They didn’t have much ammunition, however. The soldiers at the Wagon Box Fight began the battle with 7,000 rounds on hand—and this large supply saved their lives.

Once the attack began, most of Powell’s men kept their ammunition in their hats. Although this was convenient, it left their heads exposed to the sun and its sweltering heat. In addition, the troops had to deal with the stench: Indians coated their arrows with burning pitch that set fire to hay and mule and horse dung.

The soldiers’ superior firepower drove back the initial wave of Indians and they retreated to about 600 yards from the corral and spent the next few hours making separate attacks on foot.

A long fight

Powell was at one end of the corral, with Jenness stationed at the other. Participants later reported that a few Indians managed to get within 5 feet of the corral, but none penetrated the barrier.

Jenness was shot in the head and killed, as were two privates, Henry Haggerty and Thomas Boyle. Two other privates were wounded in the fight.

A teamster, R.J. Smyth, later recalled the lieutenant’s bravery during the battle. “Lt. Jenness had just cautioned me not to expose my person, and to hold my fire until I was sure of getting an Indian at each shot,” Smyth said. “He had moved a few feet from my box when he was shot through the head, I think he died instantly. He was a grand, good man, and a fearless officer. I told him to keep under cover. He stated he was compelled to expose himself in order to look after his men.”

Several soldiers wrote firsthand accounts of the ordeal. Sgt. Samuel S. Gibson, who at 18 was the youngest soldier at the corral, recorded the most detailed and dramatic version of the event. He had been dispatched to guard duty at the woodcutters’ camp and had a skirmish with several Indians before he and another soldier made it safely to the corral.

“The whole plain was alive with Indians shooting at us, and the tops of the boxes were ripped and literally torn to slivers by their bullets,” he wrote. “How we ever escaped with such slight loss I have never been able to understand, but we made every shot tell in return, and soon the whole plain in front of us was strewn with dead and dying Indians and ponies. It was a horrible sight!”

Gibson added, “The Indians were amazed at the rapidity and continuity of our fire. They did not know we had been equipped with breech-loaders and supposed that after firing the first shot they could ride us down before we could reload.”

Sometime between noon and 1 p.m., hundreds of warriors led by Red Cloud’s nephew charged the corral on horseback, hurtling toward the wagons in a V-shaped wedge. Powell later recalled that things looked very bleak at that moment, especially because ammunition was running low and his men were exhausted from holding off the Indians for so long.

After Indians on horseback were initially forced to retreat from the corral area, they tried to attack on foot over the next three hours. On Sullivant’s Ridge, a hill to the east, were several hundred Indians out of range who had been watching the battle “like spectators,” but it appeared to Powell that they would enter the fray.

A howitzer rescue

Just at that moment, though, Powell said he heard the sound of a howitzer shell hit and saw a rescue party led by Maj. Benjamin F. Smith, who had 100 men with him.

“The shell fired was in the direction of the Indians [on the hill], but fell short, as I anticipated,” Smith noted in his report, “but [it] seemed to disconcert them as a number of mounted Indians who were riding rapidly toward my command turned and fled.”

The Indians who had been attacking the corral as well as the ones watching the action all retreated.

Smith, arriving at the corral, was shocked to find that most of the men had survived the intense encounter. He had expected them all to be dead. “It was a hard lot to look at. The day was hot and the sun was beating down on them in the wagon beds,” he wrote. “The smoke from their guns had colored their faces and they looked as though they had used burnt cork on their faces.”

Each survivor received a big drink of whiskey from a keg brought along on the rescue mission by the post surgeon, Dr. Samuel M. Horton.

Indian casualties

Estimates of Indian casualties in the Wagon Box Fight, though, vary enormously; they range from two dead to 1,500. To date no one has come up with a definitive answer about why there is no agreement on the numbers.

“No [other] event has had more wild, inaccurate tales written concerning it,” writer Vie Willits Garber noted in a 1964 Annals of Wyoming article.

Two respected historians–Stanley Vestal and George Hyde–as well as several Sioux leaders said only six warriors were killed and six more wounded.

But there are accounts of people who later talked about the battle with Red Cloud. They said the chief told them that the count was much higher. Gen. Grenville M. Dodge interviewed Red Cloud in 1885, and he told him more than 1,100 Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapahos were killed or wounded at the fight. A Sioux medicine man, whose name was not recorded, visited the post of Col. Richard I. Dodge at North Platte in the fall of 1867. He told the colonel that the total of dead and injured was 1,137, and that figure was widely reported the same year as the battle.

Hyde’s book, Red Cloud’s Folk was published in 1937, based on interviews Hyde had conducted decades earlier. Hyde said that late in his life Red Cloud, who died in 1909, claimed not to remember the Wagon Box Fight at all. The historian said that was unlikely, given the large number of warriors in the battle and the fact that it marked the chief’s last major fight.

In his official report, Powell estimated 60 Indians killed and 120 wounded–figures held up to ridicule by some historians as “wildly exaggerated,” while his Army superiors believed he was being incredibly modest about the body count. Enlisted men at the scene supported much larger claims, with various shooters putting the number of dead between 300 and 800.

The account of at least one Indian warrior, an Oglala Sioux named Fire Thunder, supports the claim of heavy Indian losses. He described “dead warriors and horses piled all around the [wagon] boxes and scattered over the plain.”

In 1969, at a reenactment of the Wagon Box Fight near Sheridan, Wyo., some Indian descendants of the participants claimed Indian casualties were between 1,200 and 1,500.

Hyde said while he knew of no written accounts of the battle by Indians, they did not regard the fight as a defeat. If the reports of six dead and six wounded Indians were accurate, as Hyde believed them to be, he said they inflicted more damage to the white men at the camp and the corral because they killed a total of six soldiers and four civilians, plus capturing a large number of horses and mules.

Aftermath

In the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, with the transcontinental railroad nearing completion and opening up a new, shorter route to the Montana gold fields, the government agreed to abandon the forts on the Bozeman Trail, to make the western half of Dakota Territory a large reservation for the Sioux and to allow the tribes to hunt buffalo in the Powder River Basin of what are now Wyoming and Montana. The tribes burned the abandoned forts shortly after the Army left.

The Wagon Box Fight was the last major battle of Red Cloud’s war against the white men he felt had invaded the land they had promised to his people. Some historians credit the battle with teaching both sides valuable tactical lessons. To the Army, it was now clear that Red Cloud commanded thousands of hostile warriors, not just a small number of malcontents.

The tribes, meanwhile, became convinced that they did not have a chance against large numbers of troops unless they could secure similar firepower, which they did by the time of the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.

RESOURCES

- Bate, Walter N. “Eyewitness Reports of the Wagon Box Fight.” Annals of Wyoming 41, no. 2 (Oct. 1969): 193-201.

- FortWiki.com. “Sioux War of 1866-1868.” Accessed Feb. 28, 2014 at http://fortwiki.com/Sioux_War_of_1866-1868.

- Garber, Vie Willits. “The Wagon Box Fight.” Annals of Wyoming 36, no. 1 (April 1964): 61-63.

- Hyde, George E. Red Cloud’s Folk: A History of the Oglala Sioux Indians. Vol. 15, The Civilization of the American Indian. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1975, 159-160.

- Keenan, Jerry. The Wagon Box Fight: An Episode of Red Cloud’s War. Conshohocken, Pa.: Savas Publishing Co., 2000.

- militaryphotos.net “The Wagon Box Fight August 2, 1867” Accessed Feb. 25, 2014 at http://www.militaryphotos.net/forums/showthread.php?195915-The-Wagon-Box-Fight-August-2-1867.

- Murray, Robert A. “The Wagon Box Fight: A Centennial Appraisal.” Annals of Wyoming 39, no. 1 (April 1967): 105-107.

- The Powell Project. “James Powell Reports on the Wagon Box Fight.” The commanding officer’s official report after the battle, accessed Feb. 25, 2014 at http://powellproject.tumblr.com/post/52483831856/james-powell-reports-on-the-wagon-box-fight.

- “The Wagon Box Fight.” Annals of Wyoming 7, no. 2 (Oct. 1930): 394-401.

Illustrations

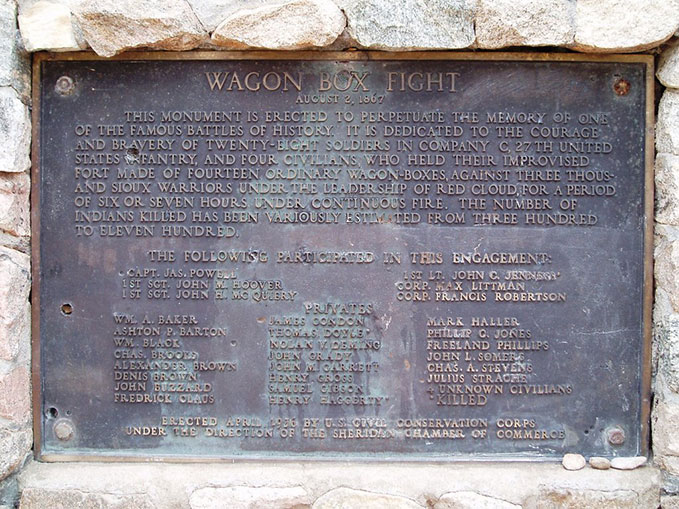

- The image of the model 1866 trapdoor Springfield rifle is from Wikipedia. Used with thanks. The photos of the monument and the main sign at the Wagon Box Fight site are also from Wikipedia. Used with thanks.

- The map of the battle site is from FortWiki.com. Used with thanks.

- The photo of the monument plaque and the view toward the mountains from the reconstructed Fort Phil Kearny stockade are by Vasily Vlasov, from Panoramio. Used with thanks.

- The photo of Red Cloud is from First People, a child-friendly site about Native Americans and members of the First Nations, with more than 1400 legends, 400 agreements and treaties, 10,000 pictures, clipart, Native American books, posters, seed bead earrings, Native American jewelry, possible bags and more. Used with thanks.