Mountain Meadows Massacre – 1889 Account

Wagon Train Members, Victims & Survivors

Historical Accounts and Testimony

“If any miserable scoundrels come here, cut their throats.” — Brigham Young

On September 11, 1857, approximately 120 men, women, and children in a wagon train from Arkansas were murdered by a band of Mormons set on a holy vengeance. Known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre, the history of this event continues to generate fierce controversy and deep emotions even to this day.

In April, the California bound wagon train assembled near Crooked Creek, Arkansas, approximately four miles south of present-day Harrison. The group included some 120-150 men, women and children, primarily from northwestern Arkansas, as well as hundreds of draft and riding horses and about 900 head of cattle. When the train began its journey it was first identified as the Baker train; however, en route, it became known as the Fancher train.

As the emigrants were traveling westward, tension was mounting among the Mormon people of Utah. Receiving distorted reports of terrible activities in the state, President James Buchanan had sent a new governor to replace the existing Mormon governor in office, Brigham Young. At the same time, there were widely reported news reports that President Buchanan had ordered a large contingent of the US Army to Utah to suppress what he believed was a “Mormon rebellion.”

These actions contributed to a general distrust of outsiders and non-Mormons as the Mormon people feared their own destruction by the federal government. As a result, Brigham Young issued a proclamation of martial law on August 5th which, among other things, forbade people from traveling through the territory without a pass. In addition, the citizens of Utah were discouraged from selling food to immigrants, especially for animal use.

It was into this atmosphere that the weary emigrants arrived in Salt Lake City on about August 10, 1857. A critical stop, the wagon train members needed to refurbish their equipment, refresh themselves and their stock, and replenish their supplies. The once friendly Mormons, usually eager to trade agricultural commodities for manufactured goods, were now hostile and reluctant to trade.

The wagon train was then told by a Mormon guide that they should take the southern route because the northern route was dangerous due to Indian attacks and had the potential for severe winter weather, while the southern route provided for more fodder for their stock and less danger.

The leaders of the train made the ill-fated decision to retrace their steps and take the southern route. However, there were some in the group who decided to continue on the path along the Humboldt River. The train was then divided with the understanding that it would later be reunited.

Though the vast majority of the train members headed southward, most historians believe today that the group easily could have made the northern trek with little difficulty. And in fact, those that did, including Malinda Cameron Scott, and her children, along with the Page Family and others, did successfully make the trek, arriving safely in California in October 1857.

As the Fancher train moved south without a pass from the Mormons, contact with the local settlers became more abrasive. Rumors began to circulate that among the Fancher party were members of a mob that killed Mormon founder Joseph Smith, Jr. years previously. The rumors were embellished with each telling and by the time the wagon train reached Cedar City, reports of gross misconduct were believed. With hungry bellies and injured feelings, the Fancher train proceeded through Cedar City westward as the locals held meetings to determine what was to be done about the interlopers.

At the edge of the desert between Utah and California, about 35 miles southwest of Cedar City, the wagon train stopped to rest and recuperate for several days in a meadow surrounded by numerous springs. In the meantime, the militia back in Cedar City had decided that the Fancher train should be eliminated.

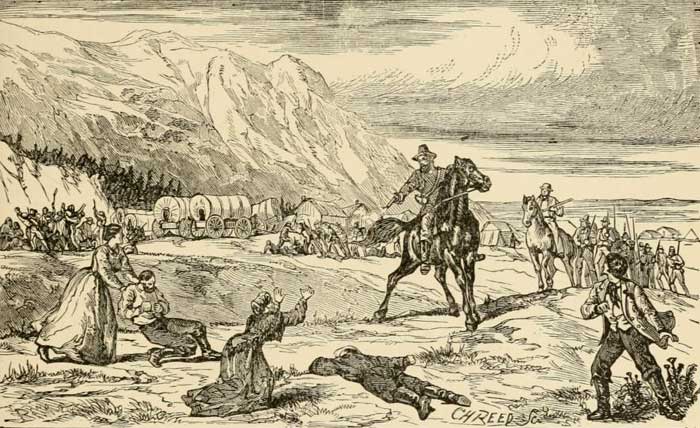

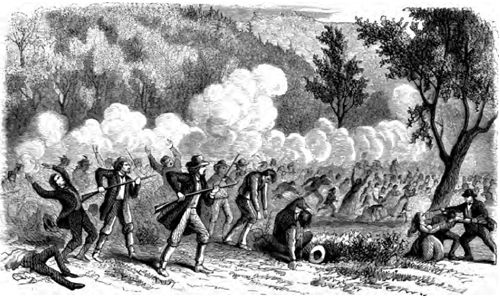

At dawn on September 7, 1857, the travelers were besieged by Mormon-allied Paiute and militiamen disguised as Indians. Though the wagons were drawn into a circle, making a strong defensive barrier, seven were killed and 16 wounded in the first assault. For the next five days, the siege continued while the wagon train resisted.

On Thursday evening, September 10th, Major John M. Higbee handed John D. Lee orders from Colonel Isaac C. Haight in Cedar City to “decoy the emigrants from their position, and kill all of them that could talk.

On Friday morning, September 11, 1857, John D. Lee carried a flag of truce to the encamped wagon train. The party, low on water and ammunition, welcomed the militiamen believing that they had arrived to save them. The emigrants were made an offer to leave all of their possessions to the Indians and be conducted safely back to Cedar City.

Eagerly accepting the conditions, the small children and wounded were placed in the wagons, followed by the women and older children walking in a group. The men trailed the women, walking alongside their armed militia protectors.

After having traveled about a mile and a half, Major John M. Higbee rose up in his stirrups and shouted “Do your duty!”, whereupon all but the young children were slaughtered, either by their armed escorts or by hidden Paiute. An estimated 120 unarmed men, women, and older children were killed; 17 of the younger children under the age of seven were spared.

“The scene was one too horrible and sickening for language to describe. Human skeletons, disjointed bones, ghastly skulls and the hair of women were scattered in frightful profusion over a distance of two miles.”

— A traveler passing through the area in 1859

No effort was made to give the bodies a decent burial and over the next two years, foraging animals scattered the bones over a great distance.

Two days after the massacre, a messenger from Salt Lake City arrived with Brigham Young’s advice to let the wagon train pass without molestation.

The two wagon loads of children who had not been killed were adopted into Mormon homes.

Appalled by what had been done, and in fear of possible repercussions, Brigham Young led a church cover-up, saying that the Paiute were responsible for the massacre. He wrote that the pioneers had caused the death of a number of Indians by giving them poisoned meat, and by poisoning some of their wells. The cover-up continued to be maintained for the next few years in the face of outside outrage and investigation.

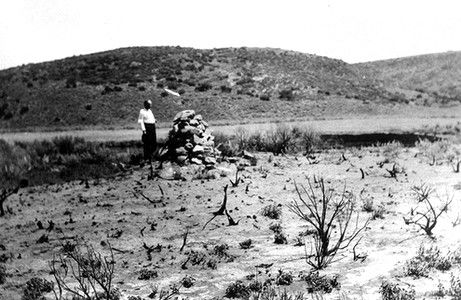

A rock cairn was erected with a carved stone and the words “Here lie the bones of one hundred and twenty men, women and children from Arkansas, murdered on the 11th day of September 1857.” An officer painted a cross-line beam above the cairn with the words “Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord. I will repay.” Captain James Lynch of the U.S. Army took possession of the young survivors and returned them to relatives in Arkansas. The children arrived in Carroll County on September 15, 1859, two years after the massacre.

“The Mountain Meadows Massacre stands without a parallel amongst the crimes that stain the pages of American history. It was a crime committed without cause or justification of any kind to relieve it of its fearful character… When nearly exhausted from fatigue and thirst, [the men of the caravan] were approached by white men, with a flag of truce, and induced to surrender their arms, under the most solemn promises of protection. They were then murdered in cold blood.”

— William Bishop, Attorney to John D. Lee

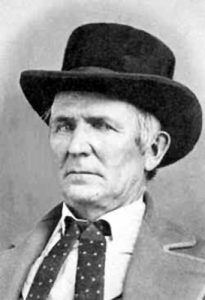

Although there were many investigations, no punishment was handed out for the crime until 20 years later. John D. Lee, Major of the Fourth Battalion of the militia at Harmony, was excommunicated from the Mormon Church and later made the scapegoat in the entire affair. Tried twice, he was finally convicted and executed by firing squad at the siege site on March 23, 1877, for his role in the affair.

Before his death, Lee wrote out a full confession admitting his reluctant complicity. He claimed he was a scapegoat for the many Mormons, including leaders George A. Smith and Isaac C. Haight at the least, responsible for the massacre. In May 1961, the Mormon Church posthumously reinstated Lee’s membership.

The entire truth of the matter will probably never be known because most of the documents and diaries of the participants were destroyed. The extent of Paiute participation in the massacre is a point of disagreement among researchers. Some allege that some of the Mormon militia were dressed as Native Americans. The extent of Mormon participation is also a point of disagreement. Some say the ordering authorities in Cedar City had sent a messenger to Salt Lake City seeking direction from President Brigham Young, and his belated response would allegedly have averted the massacre. Others are unconvinced that even this would absolve Young from responsibility, given the extent of his authority and influence as the leader of the Mormons.

In 1999 a new memorial to the pioneers was erected in Mountain Meadows, Utah and is maintained by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Directions:

From Cedar City, north of St. George on Highway15, go west on state highway #56 about 35 miles to the intersection of state highways #56 and #18. Turn south on #18 and go about 11 miles to Enterprise. Continue on south approximately 5 more miles to the Mountain Meadows Massacre site. The monuments are on the south end of the valley.

© Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated March 2020.

“I had many to assist me at the Mountain Meadows. I believe that most of those who were connected with the Massacre, and took part in the lamentable transaction that has blackened the character of all who were aiders or abettors in the same, were acting under the impression that they were performing a religious duty. I know all were acting under the orders and by the command of their Church leaders; and I firmly believe that the most of those who took part in the proceedings, considered it a religious duty to unquestioningly obey the orders which they had received. That they acted from a sense of duty to the Mormon Church.” – Life and Confessions of John D. Lee

Also See:

Brigham Young – Leading the Mormons

Sources:

Mountain Meadows Association

Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation

1857 Iron County Militia

Gibbs, Josiah F., The Mountain Meadows Massacre; Salt Lake Tribune Publishing Co., 1910