Despite its great length and considerable weight by modern standards, longarms such as this British Model 1756 Light Dragoon Carbine (above) were slung along with one or a pair of pistols like the Elliot’s Pattern of 1759 Light Dragoon example (top) and a sword by such horsemen as this British Light Dragoon of the 17th Regiment.

When well-trained and equipped, a determined light horseman of the American Revolution was a fearsome combined-arms foe. The adroitness of a British Light Dragoon using all of his arms is impressively described by an eyewitness: “ … In passing near a thicket he was fired at by some of the Provincials; he instantly pretended to fall from his horse, hanging with head down to the ground, which the Light-Horse do with great ease. The Americans, four in number, supposing him killed, ran from their cover to seize their booty; but when they came within a few yards of him, the Light-Dragoon in an instant recovered his saddle, and with his carbine shot the first of them dead, he then drew his pistol and dispatched the second, and immediately attacked the other two with his sword who surrendered themselves his prisoners … .”

Mounted units were utilized heavily during the American Revolution, although not in the numbers or the grand, decisive, massed charges seen on the plains of Europe. More often than not, light horsemen were used as scouts on raiding parties, for foraging operations and as messengers or escorts. The walled, fenced and wooded terrain rarely permitted major mounted operations on the battlefield; despite some decisive charges at Cowpens in South Carolina and Guilford Court House in North Carolina, even those actions employed relatively small numbers. Indeed, the British sent only two regiments of Light Dragoons to fight in the colonies: the 16th (Queen’s) and the 17th. The 16th was drafted in 1778 and later returned to England, the British deciding to place more reliance on newly raised Loyalist horse units, such as the British Legion (Tarleton’s), Queen’s Rangers, Diemar’s Hussars and many others. Late in the war, they raised the King’s American Dragoons into which many of the smaller Loyalist mounted units were assimilated, though eventually that well-appointed and fine regiment ultimately saw little service. The Hessians contributed a company of mounted Jaegers, and there was also a regiment of Brunswick Dragoons that served mostly on foot but was equipped with carbines and broadswords.

Horsemen Under Arms

The sword was always considered the primary weapon for regular light cavalry, and the troops were often admonished not to break the impetus of the full-tilt saber charge by stopping to fire their pistols or carbines.

Pistols, however, were widely used and proved invaluable during close-quarters fighting. Generally, they were mounted across the pommel of the saddle with leather or bearskin flaps to keep them secure and dry and were instantly available to the rider. One of the most famous cavalry engagements of the war occurred at Cowpens. Near the end of the battle, renowned American cavalryman Col. William Washington, in a melee with British and Loyalist cavalry, found himself cornered with a broken sword. A British officer made a thrust at Washington when, “ … a boy, a waiter, who had not the strength to wield his sword, drew his pistol and shot and wounded this officer. Which disabled him … .” Moments later, Washington’s horse was killed by a pistol shot from another British trooper.

Not all pistols were carried in saddle holsters, as an account of one of Maj. John Graves Simcoe’s men with a Stockbridge Indian shows. “ … French, an active youth struck at an indian, but missed his blow: the man dragged him from his horse, and was searching for a knife to stab him, when, loosening French’s hand, he luckily drew out a pocket pistol, and shot the indian thru the head … .”

Good pistols were often in short supply on both sides. When Simcoe formed the small Hussar troop for his Loyalist Queen’s Rangers, he stated: “[T]he mounted men, termed Huzzars, were armed with a sword and such pistols as could bought or taken from the enemy … .” indicating that the British had none on hand to supply him with.

As a rule, a regular light horse trooper ideally carried a carbine in addition to a sword and one or two pistols mounted in saddle holsters. His carbine was slung from a broad leather sling over the shoulder and could quickly be brought up to firing position and then dropped down without loss after the shot. Some units, however, dispensed with the carbines altogether or could not get them. Even certain Loyalist mounted contingents were destitute of carbines and had to make do with shortened muskets. In August of 1781, The King’s “Carolina” Rangers Troop of Light Dragoons were issued “10 French Muskets cut short” and “45 British Muskets, cut short.”

Mounted irregulars and militia were armed with a hodgepodge of everything when it came to firearms. Infantry muskets, hunting guns and even rifles were in use by mounted men. A Patriot company of 56 mounted men raised in North Carolina during 1781 could only report having 15 pistols between them but were completely equipped with rifles, which were slung under the right arm with the muzzle in a leather socket attached to the stirrup. The pistol-armed recruits carried them hanging from a belted leather strap on the left side so as to be able to carry them when fighting dismounted. With rifles and sabers, these men were more on the order of what Europeans would term dragoons.

Cavalry In Action

A British officer aptly described the mounted Patriot militia in the South, “ … The crackers and militia in those parts of America are all mounted on horse-back … . When they chuse to fight, they dismount, and fasten their horses to the fences and rails; but if not very confident in the superiority of their numbers, they remain on horseback, give their fire, and retreat, which renders it useless to attack them without cavalry … .” One of accomplished partisan leader Francis Marion’s men wrote, ”from our prisoners in the late action, we got completely armed; a couple of English muskets, with bayonets and cartouche-boxes, to each of us … ,” and later on, “we got eighty-four stand of arms, chiefly English muskets and bayonets … .” On another occasion, when Marion’s horsemen were being pursued by some British Light Dragoons, “Scorning to fly from such a handful, some of my more resolute fellows, thirteen in number, faced about and very deliberately taking their aim at the enemy as they came up, gave them a spanker, which killed upwards of half their number … .”

The Loyalists fighting with the British were not much different. In 1782, Loyalist Benjamin Thompson commented on two troops of Tory South Carolina militia cavalry (which he called “Hussars”) commanded by Cunningham and Young. “The principal objects of the expedition were to practice the Cavalry in marching in Regular order in the Enemy’s Country, and to accustom them to act with the mounted militia, who will be very useful in covering our flanks. They are all armed with rifles as well as Swords, and are perhaps the best marksmen in the world for shooting on horse back … .” Being generally less adept or unfurnished with the saber, mounted irregulars on both sides often relied on firing their longarms from the saddle.

Equipping The Continental Cavalry

Arms of every sort were always wanting for the mounted arm of the Continental Cavalry. In 1777, Congress authorized four regular regiments of Light Dragoons, which rarely fielded more than 150 mounted personnel each. All four served throughout the entire war with detachments present in most the major campaigns. The 3rd Regiment commanded by Lt. Col. William Washington saw the most extensive service in the south and compiled a superb battle record. Supplementing these regiments were additional troops of light horse in mixed foot and horse legions, such as Armand’s, Lee’s and Pulaski’s. Acquiring appropriate cavalry firearms was even more of a problem for the Patriot forces.

Washington wrote:

Head Quarters, Valley fit out,April 29, 1778.

“Dear Sir: I received yours of the 21st. instant. I am as much at a loss as you can possibly be how to procure Arms for the Cavalry, there are 107 Carbines in Camp but no Swords or Pistols of any consequence. General Knox informs me, that the 1100 Carbines which came in to the Eastward and were said to be fit for Horsemen were only a lighter kind of Musket. I believe Cols. Baylor and Bland have procured Swords from Hunter’s Manufactory in Virginia, but I do not think it will be possible to get a sufficient Number of Pistols, except they are imported on purpose … ” and “By a letter from Colo. Moylan a few days ago, I find that his Regiment and Sheldon’s will want Arms, swords and pistols in particular, and as they are not to be obtained to the Northward, I beg you will engage all that you possibly can from Hunter.”

In November of 1778, a supply of 1,500 pairs of pistols, 250 carbines and six chests of sabers arrived from France, but this may have proved to be only a temporary fix, and a lack of everything dogged the cavalry throughout the war.

The Cavalry Saber

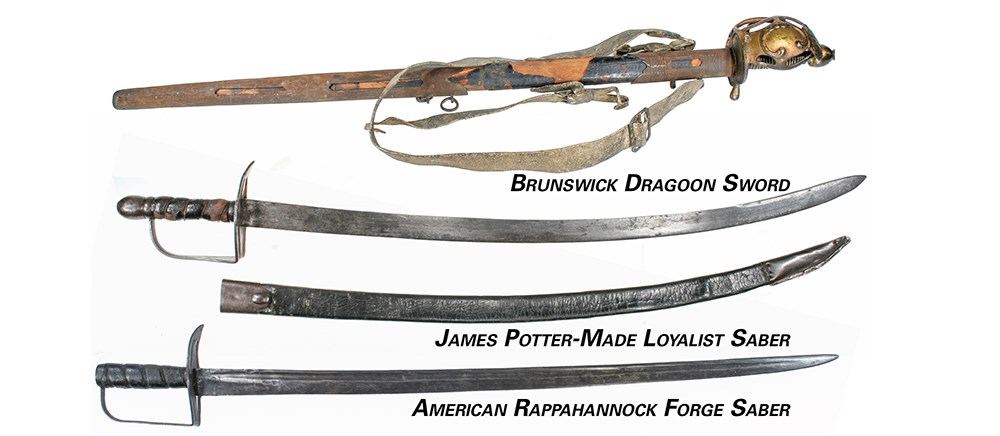

Any discussion of cavalry arms must at least touch on the most essential weapon of the horseman: his sword. Before 1788, the British had no universal patterns, each regiment choosing the style it favored. Sabers for the Loyalist Horse (sturdy but crude copies of the British sabers) were produced by James Potter in occupied New York City, and so many fell into the hands of the Patriots that Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee could boast the men of his unit were fully equipped with them. Massive broadswords of the Brunswick Dragoons surrendered at Saratoga in 1777 were issued to the 2nd Continental Light Dragoons who liked the beefy, iron-mounted wooden scabbards. James Hunter at the Rappahannock Forge in Virginia also produced an iron-mounted saber based on a captured British specimen. A number of brass-hilted sabers from France supplied to Virginia also helped to supplement the other sources.

Cavalry Pistols & Carbines

While many other varieties of arms may have been used, due to a lack of space, only the principal types will be discussed here. The primary British pistols were the Elliot’s Pattern (with a 9″ barrel) and possibly some of the Royal Foresters Pattern. Specimens of the Elliot marked to both the 16th and 17th regiments have been found, and the American-made Rappahannock Forge pistol is a very close copy of it.

Modest numbers of French military pistols were also available to the Colonial forces, and these were primarily the 1733, 1763/66 and possibly some of 1777 patterns. Some more rudimentary local gunsmith products were also put into service but probably constituted a fraction of the various types used. Officers often carried much higher-quality pistols, sometimes silver-mounted, which they either purchased with their own funds or obtained through capture.

The Continental Dragoons used what carbines they could get, whether through captures from the British, locally made arms or a few supplied by the French. There is at least one Model 1733 French Carbine branded “United States,” and parts of the 1766/70 Model Dragoon Fusil have also been excavated in American campsites. Small numbers of pistols were also produced, the most notable being those made at the Hunter Works at Rappahannock Forge in Virginia.

While not employed in the same numbers or a manner typical of traditional 18th-century warfare, cavalry played important roles on both sides of the American Revolution. Many prominent personalities of the war served in cavalry units, such as Banastre Tarleton of the 16th Light Dragoons, later commander the Loyalist British Legion, who famously captured Gen. Charles Lee in December of 1776. Major Benjamin Tallmadge of the 2nd Continental Light Dragoons became Gen. George Washington’s trusted spymaster, and his unit earned the nickname of “Washington’s Eyes” due to their intelligence-gathering activities. “Light Horse Harry” Lee became one of the most famous cavalrymen in the Continental Army, heading up his own Lee’s Legion to great success throughout the war. A look at the American Revolution is incomplete without understanding the horsemen who fought it and the arms they carried.