After he blew the top strap and cylinder of an old .45 Colt SAA by grinding the black powder into finer granules and putting all he could into the .45 case, Elmer Keith “discovered” the .44 Special, which had been around for 20 years even though he had never seen one, and quickly unlocked its potential. He eventually settled on a load of 18.5 grains of Hercules 2400 under the Keith-designed Lyman No. 429421 250-grain hard-cast bullet in the era’s larger-capacity balloon-head .44 Special brass.

In duplicating this load in balloon-head brass, I found the muzzle velocity to be just over 1,200 feet per second from a 71⁄2″ barrel. When newer solid-head brass arrived in the 1950s, his load was dropped to 17 to 17.5 grains. Keith spent 30 years asking ammunition companies to offer a .44 Special load with a 250-grain bullet at 1,200 fps. He finally got what he asked for, and more, in the new .44 Magnum with a 240-grain bullet at 1,450 fps.

Keith Made It Work

Keith retired his .44 Specials in favor of the new cartridge, carrying a 4″ Smith & Wesson .44 Magnum daily until his incapacitating stroke in 1981. While he was happy with the new sixgun and the concept, the actual ammunition offered by Remington left something to be desired. The Lubaloy bullets were too soft resulting in barrel leading and Keith felt the pressures were much higher than they should have been.

He soon found a better load, which soon became such a standard it was simply known as the Keith Load — his Lyman No. 429421 hard cast 250- grain bullet over 22 grains of No. 2400 over standard primers. Be informed — it takes about 6 percent less of today’s Alliant No. 2400 to produce the same results Keith’s load did in 1956. Despite ever more powerful cartridges, such as the .454, .475, and .500, this remains a very powerful load and recoil in a 4″ .44 Magnum has not been diminished in any way, shape or form.

Originally, Smith & Wesson 1950 Target .44 Specials were assembled with specially heat-treated cylinders and frames, prototypes of the new .44 Magnum. The 1950 Target with a 61⁄2″ barrel weighed only 39 ounces resulting in excessive recoil — to the shooter, not the gun. Weight was added by using a bull barrel and full-length cylinder filling most of the frame window. The weight of the final production 61⁄2″ .44 Magnum was 48 ounces or an even three pounds.

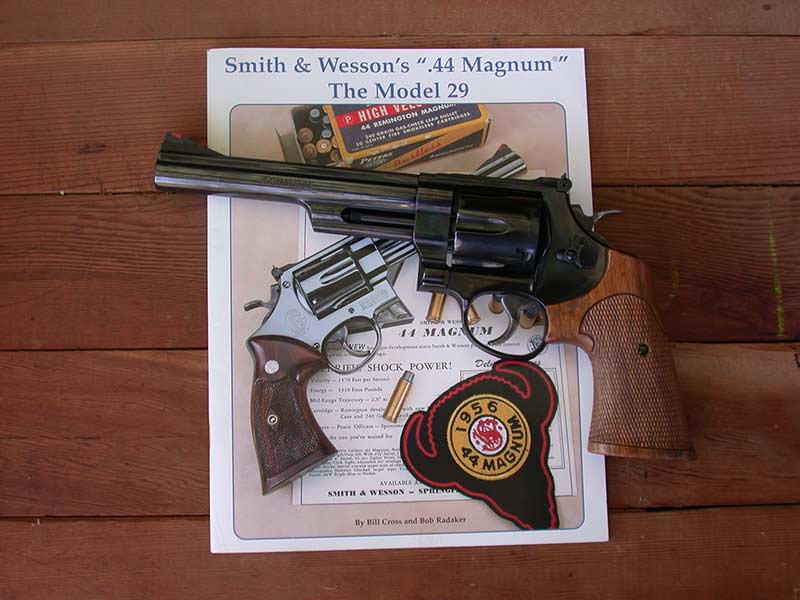

The .44 Magnum Is Born

The early Smith & Wesson .44 Magnums were beauty personified. Not only did they carry a beautiful finish known in those days as S&W Bright Blue, they also came very close to, perhaps even equaled, the precision fitting of the 1907 Triple-Lock. The new .44 Smith & Wesson, superbly finished with a magnificently smooth action and trigger pull, sold for $140. As a teenager I was making $15 a week with a paper route and could only dream of great sixguns. I graduated from high school and moved up to big money — 90¢ an hour — and it was time to start buying my own sixguns.

One of the first .44 Magnum 4″ models to hit my part of the country was rented out by a local gun store/outdoor shooting range. Three of us teenagers stepped forward to shoot, and although the recoil was absolutely awful, none of us would admit it and definitely not to each other.

The Anniversary Model 29 from Smith & Wesson comes with a wooden presentation

case just as it did 50 years ago. The 50th Anniversary Model 29 is the 21st century

version of the original .44 Magnum. The new sixgun does not have counterbored

chambers or a pinned barrel, but is otherwise a beautifully made piece.

Lace Panties?

Those first .44 Magnums appropriately resided in fitted wooden cases. Guides and outfitters traded in their .357s for the new .44 and a few handgun hunters began using the Smith & Wesson very successfully. However, soon gun stores had used .44 Magnums for sale with a box of cartridges holding six empties and 44 .44s still intact. One cylinder full was all it usually took for many a shooter to realize this was more

pain than desirable.

Remember, this was the 1950s when heavy handgun recoil was represented by the 1911 .45 ACP and relatively heavy .357 Magnum. There were no hard-kickin’ handguns until the .44 Magnum arrived. A well respected writer of the time, Major Hatcher of the NRA Staff, likened the recoil of the .44 Magnum Smith & Wesson to being hit in the palm of the hand with a baseball bat. Keith said it was not as bad as shooting a 2″ Chief’s Special .38, while Col. Askins, always the pot stirrer, countered with anyone who could not handle the recoil should wear lace panties.

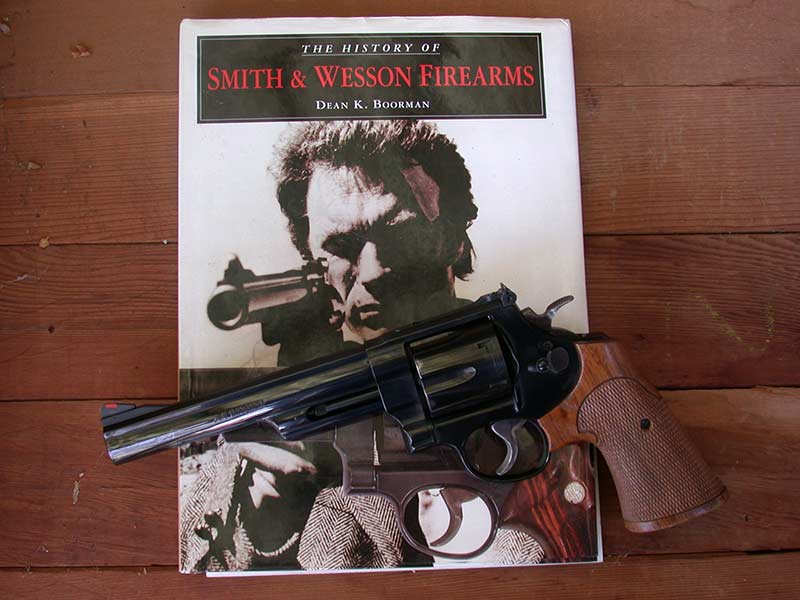

Unreal Demand Becomes Real

Only the most serious shooters chose the S&W .44 Magnum before the arrival of Dirty Harry. Clint Eastwood’s famous character, whose exploits began in the early 1970s, created an unreal demand for the .44 Magnum not satisfied no matter how much Smith & Wesson increased production. Suddenly .44 Magnums, which had been selling less than retail, were going for double retail and more. The demand created by the movies was unreal and destined to wear itself out, but a real demand was created by two sixgunning activities which really took off in the late 1970s, namely handgun hunting and long range silhouetting.

With the rise of handgun hunting and heavier sixguns, the reloading of the .44 Magnum changed dramatically. The old standard Keith load had been his 250- grain hard-cast semiwadcutter bullet over 22 grains of No. 2400 was, and remains an excellent hunting load. But as bigger and bigger game, including elephant and Cape buffalo were hunted with the .44 Magnum, the standard hunting load became a hard-cast 300- or 320-grain bullet at 1,300 to 1,400 fps.

In Denial

When silhouetting came on the scene, the Smith & Wesson .44 Magnum was an early favorite. Used sparingly with full-house Keith loads, the S&W performed normally, but shooters soon discovered it would not take the constant pounding of a steady diet of heavy loads. Even though Keith

waited 30 years for his “.44 Special Magnum” he reported in the 1957 Gun Digest firing 600 rounds through his .44 Magnum in the course of a year. That averages to less than 12 rounds a week and no problems were reported.

However, as silhouetters used thousands of rounds in practice and competition, the big Smith started to shoot loose. Parts wore quickly and some sixguns unlocked on firing allowing the cylinder to rotate backwards placing an empty round under the hammer upon the next shot. Smith & Wesson ignored or denied these problems until the 1980s when they announced internal changes to prevent these occurrences.

The Classic Sixgun

Today, collectors refer to the early guns as pre-29s as the .44 Magnum became the Model 29 in 1957 when all Smith & Wesson handguns were de-personalized with model numbers instead of such great names as .357 Magnum, .38/44 Heavy Duty, Highway Patrolman, Combat Magnum, and of course, .44 Magnum. Those very first .44 Magnums are also known as five screws as they had four sideplate screws and one screw entering from the front of the triggerguard. In 1956 they became four screws with the elimination of the upper sideplate screw, and the 83⁄8″ barreled version arrived in 1958 after going to four screws. The same year also saw a special run of approximately 500 Model 29s with 5″ barrels.

Win A Little, Lose A Lot

Over the years, the Model 29 went through a series of changes. In 1960 it became Model 29-1 when the extractor rod was changed to a reverse thread. The 29-2 arrived in 1961 with the changing of the cylinder stop and the dropping of the triggerguard screw, followed by the elimination of the diamond in the center of the grip in 1968. The prefix of the serial number went from S to N in 1969, and then someone must have had a very bad weekend in 1979 when the 61⁄2″ barrel length was changed to 6″. This should never have happened. The 6″ never quite balanced or looked right and was definitely an extreme case of fixing what ain’t broke.

As if to add insult to injury, the Model 29-3 arrived in 1982 without the recessed cylinder and pinned barrel. At the tail end of the 29-3 production in 1987 Smith & Wesson started the Endurance Package which was carried into the 29-4 in 1988. Two years later the 29-5 saw the introduction of longer bolt slots in the cylinder as well as more internal modifications. By 1994 the wooden stocks, which had gone from fairly usable and comfortable to a very blocky shape uncomfortable with all loads, were replaced by Hogue rubber stocks, the top was drilled and tapped for scope mounts, and the front of the rear sight leaf was changed from square to semicircular. This was the Model 29-6. The 61⁄2″ barrel, the pinned and recessed features, the original stocks were all gone and another radical change appeared when the long familiar square grip was dropped for a round butt in 1995. Forty years after the original appeared it was now “improved” to the point of hardly being recognizable. The Model 29 also appeared as a 101⁄2″ Silhouette Model with special sights and then the Classic, Classic DX, and Magna Classic with full under lug barrels.

Burial And Resurrection

By 1998’s 29-7, the final changes were made. It now had a MIM trigger and hammer, a frame-mounted firing pin, and more changes to the lock works. All of the changes are not necessarily bad, but it wasn’t the original .44 Magnum. In 1999, Smith & Wesson blew taps over the Model 29 and it was gone, dead and buried. The original had changed so much hardly anyone missed it.

Now the Model 29 is back. No, it is not exactly the same as it was 50-years ago. The original .44 Magnum was built on a design from the 19th century originating in the Military & Police of 1899. Working by 21st century standards and production methods, Smith & Wesson has done an excellent job resurrecting the original .44 Magnum. Some things are the same, some are different and the phrase of the day is “No Whining.” Yes, my spiritual side would have preferred an exact duplicate, however, my realistic side says this’ll never happen.

The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly

Let’s look at the 50th Anniversary Model of the Smith & Wesson .44 Magnum. The Bright Blue finish almost rivals the old, the sights are a white outline rear and a red ramp front as on the original, and the barrel length is the original 61⁄2″. The hammer and trigger are the original checkered and serrated style and, from the side, the hammer has the best looking profile I’ve seen on a Smith & Wesson or any other factory-produced sixgun for that matter.

The stocks are good news/bad news. The good news is they are the same color, though a lighter shade, as the originals and have the diamond around the grip screw. They also feel much better than the originals being slightly thinner in overall feel and tapered quite a bit to the top of the grip frame. Unfortunately, they are not inletted to the grip frame and depend on pins to hold them solidly. It doesn’t work and

they move when firing even heavy .44 Special loads, so it seemed both prudent and appropriate to replace them with a tight-fitting pair of Herrett’s Trooper stocks almost as old as the original .44 Magnum. The grip frame is a square butt and original .44 Magnum stocks fit, so both the original barrel length and grip-frame configuration are back. The pinned and recessed features are missing and the firing pin is mounted in the frame instead of the hammer.

Yes, it has the internal lock found on all Smith & Wesson revolvers and comes in a lockable, padded plastic case. The sides of the barrel are marked as the original was though in reverse with the left side of the barrel marked “44 MAGNUM”, while the right side carries “SMITH & WESSON.” Since this is a 50th Anniversary Model, there is a gold seal on the right side of the frame announcing “50th ANNIVERSARY, SMITH & WESSON” above the S&W logo with “1956-2006, 44 MAGNUM” found below. All in all this is a most attractive sixgun and I applaud Smith & Wesson for bringing back the best possible 21st century version of the original .44 Magnum.

Shoots Fine

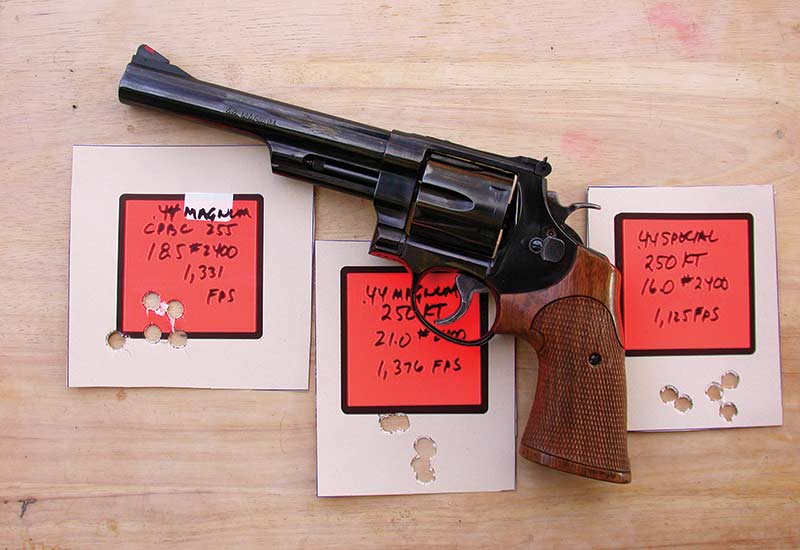

The new Model 29 was tested with both .44 Special and .44 Magnum handloads in very shooter unfriendly conditions with a temperature of 33 degrees and a numbing wind. I would load the sixgun and quickly put on wool knit gloves to fire. In between, I headed for the 4×4 to warm up. Even so, the 50th Anniversary Model performed very well. In Starline .44 Special brass, the 250-grain Keith bullet over 16 grains of No. 2400 clocked 1,125 fps and grouped 13⁄8″ for five shots at 20 yards, while the same bullet over 7.5 grains of Unique or 17.5 grains of H4227 went 975 fps and grouped into 11⁄2″. The best groups came from Starline .44 Magnum brass with a Cast Performance Bullet Co. 255-grain Hard

Cast over 21 grains of 2400 for 1,331 fps and a group of 1″, while the 250- grain Keith over 21 grains of 2400 grouped into 11⁄8″ and clocked 1,376 fps. All loads were chronographed using the easy to set-up and use (really appreciated in cold weather!) PACT Professional Chronograph XP.

The Smith & Wesson Model 29 is the sixgun by which all other .44 Magnums are judged. When it comes to performance some fall short, other surpass it. I view it as the finest-looking doubleaction revolver ever made, and it is definitely the slickest handling of all .44 Magnums. For an everyday Packin’ Pistol with standard loads using 240- to 250-grain bullets or heavy-duty .44 Special loads, it is still top of the mountain when it comes to double-actions. One miracle occurred with the return of the Model 29, it would only take a minor miracle to make it a standard production item next year offered in both 4″ and 61⁄2″ versions. One can hope. Shooting the new old 29 took my mind, soul and spirit back 50 years.