A Fifty-Year Wound

HRNM Docent & Contributing Writer

|

| William L.McGonagle (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph) |

On June 11, 1968, in Leutze Park at the Washington Navy Yard, Secretary of the Navy Paul R. Ignatius and Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, chief of naval operations, awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor to Captain William L. McGonagle, commanding officer of USS Liberty (AGTR 5), for performance above and beyond the call of duty on June 8, 1967, when that ill-fated ship was attacked without warning by air and surface craft of the Israel Defense Forces.(1) The travail of that ship and her crew resulted from actions that have never, in the view of many of those who were on board, been truthfully explained by the attackers. However, the medal and many others earned as the result of that confrontation on the high seas are talismans of brave and selfless acts by a host of officers and enlisted personnel of the U.S. Navy.

The Humble Origins of a Spy Ship

|

| SS Simmons Victory in New York, 1947. (World Ship Society via navsource.org) |

Liberty began her life as SS Simmons Victory, a Victory-class cargo ship built during the Second World War by the Oregon Shipbuilding Company of Portland, Oregon and named for Simmons College in Boston, Massachusetts. Completed about two months after being laid down, she was delivered to the War Shipping Administration on May 4th, 1945, and performed strategic lift operations under charter to the Pacific Far East Line, to include delivering ammunition from Port Chicago, California to Leyte for the impending invasion of Japan. Japan’s surrender in August obviated the necessity for this operation, and she returned the ammunition to Port Chicago. During the Korean War, she carried out similar duties. Simmons Victory was withdrawn from service in 1958 and placed in the National Defense Reserve Fleet in Olympia, Washington.

Acquired by the Navy in February 1963, Simmons Valley was converted to a “miscellaneous auxiliary ship,” and commissioned as USS Liberty on December 30, 1964, at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. She steamed to Norfolk in early 1965 for installation of equipment that would enable her crew to conduct communications surveillance and processing operations for the National Security Agency. Liberty was assigned to Service Squadron Eight, and following shakedown at Naval Base Guantanamo Bay began deployment to the west coast of Africa to participate in the Navy’s program of research and development in communications.

Liberty’s operations, and those of other technical research ships such as USS Banner (AGER 1), USS Pueblo (AGER 2), and USS Palm Beach (AGER 3), have retained a somewhat murky, mysterious character, though the role of the National Security Agency as an eavesdropping organization has more recently become publically known. The ships chosen for these missions were older, nondescript cargo vessels of uncertain pedigree that could be easily converted and equipped with costly electronic communications surveillance equipment. Publicly available information shows that, prior to her fateful voyage to the vicinity of the Sinai Peninsula, Liberty made three deployments to the West Coast of Africa between the Canary Islands and the Cape of Good Hope as “a floating research and development ship.”(2)

Into Harm’s Way

Liberty’s third deployment was interrupted by orders received during the morning watch on May 24th, 1967 at Abidjan, Ivory Coast, where the ship’s crew was enjoying a liberty port. The ship was ordered to proceed over 3,000 miles at best speed to Rota, Spain. There, she was to take on additional personnel and equipment for sensitive assignments in connection with worsening tensions between the United Arab Republic (present-day Egypt) and the State of Israel. Following an eight-day voyage, Liberty entered Rota, took on stores, equipment, additional linguists and technical personnel, and departed for the Eastern Mediterranean on June 2, 1967.

Officers and enlisted personnel on board the ship and those in supervisory positions expressed misgivings about the impending mission. Perhaps it was best expressed by Chief Petty Officer Raymond Linn, who was to retire at the end of June after 30 years’ service. He opined that it was foolhardy to send an unarmed ship, a spy ship, into such a potential maelstrom. Chief Linn proved all too prescient, as he would become one of 34 crewmen who would die in the attack. Others at higher levels expressed uncertainty, and Cdr. McGonagle made a request for a destroyer type escort. The request was denied for, among other reasons, the ship had every right to be where she was and was clearly identifiable as a United States Ship. Finally, it was assumed that the ship could withdraw from danger if need be.

The intensity of hostilities during what would become known the Six Day War was such that those higher up in the chain of command modified operational orders, not simply for USS Liberty, but for all Sixth Fleet ships. In summary, new orders stipulated that areas might be modified based on “the local situation” and that the Sixth Fleet Commander was to be advised by flash message of “any threatening actions to you or diversions from schedule necessitated by external threat.” These messages, and those restricting a closest point of approach to 20 (and later, 100) miles from the hostile coast, did not reach Liberty.

Prior to reaching the operating area, Cdr. McGonagle had met with Lt. Cmdr. Dave Lewis, Liberty’s Research Department director, to confirm that it was absolutely necessary to be as close to the Gaza Strip as set forward in orders to execute the mission. McGonagle had also instituted a “modified” weapons condition three steaming watch that placed ammunition and extra personnel at the forward .50 caliber gun mounts.

|

| A painting of USS Liberty, Oil on Silk; Artist Unknown; C. 1967. (Gift of Ms. Cindy McGonagle, Naval History and Heritage Command image) |

Liberty arrived off the city of El Arish, about 30 miles west of the Gaza Strip on the northern coast of the Sinai Peninsula, just after midnight on June 8th, 1967. There, a tale of bravery, perseverance and sacrifice, unique in the annals of the U.S. Navy, would play out. By late morning she had been overflown by multiple aircraft, both ungainly “flying boxcar” Noratlas 2501 types, and fighter bombers. One of the boxcars reportedly had Star of David markings. It was, in the words of one of the officers of the deck, Ens. John Scott, a beautiful day, and the American flag was clearly visible. All crewmembers later queried agreed that the flag was clearly visible prior to and during the attack. Some members of the crew even sunbathed on deck before a General Quarters drill was held at 1300 that afternoon.

About one hour later, a savage air attack began and in the words of then-Lieutenant George Golden, Liberty’s chief engineer, “all hell broke loose.” Repeated strafing by Mirage III fighters and Mystere fighter-bombers left the bridge in shambles, with the navigator dead, the executive officer mortally wounded, and the officer of the deck and the commanding officer severely wounded. The ship’s bridge area was in flames from burning napalm, and the superstructure was repeatedly penetrated by rocket fire. Years later, Golden recounted that three flags, including a large “holiday ensign,” were raised and shot away.(3) A shipyard survey later tabulated 821 holes made in Liberty’s hull, deck, and superstructure.

During the initial attack, the forward .50 caliber machine gun positions were destroyed and the crews killed. Communications antennae were destroyed, and the ship was quickly rendered defenseless and mute. The air assault was followed by a surface engagement in which three Israeli torpedo boats rapidly closed in and launched torpedoes, one of which made a 40-foot gash, starboard side amidships, flooding the Research Department spaces and killing all inside.

Amid the massive, sudden destruction, the well-trained crew responded with instinctive professionalism and consummate bravery. Lt. Richard Kiepfer, the ship’s doctor, rescued those wounded from exposed decks at great risk to himself. Helmsman Francis Brown remained at his post, despite heavy shelling, until he was killed by a projectile that struck him from behind. Executive Officer (XO) Phillip Armstrong was fatally injured by strafing as he jettisoned 50-gallon gasoline drums from the bridge. Everywhere crewmen performed gallantly, to include those initially temporarily overcome by fear. Dr. Kiepfer, though wounded himself, operated in a vain attempt to save Gary Blanchard, a young seaman from Kansas.

During the initial attack, radiomen were able to send a distress message which was received on board the carrier Saratoga (CVA 60) using jury rigged equipment, but the signal was jammed intermittently. Rescue ships and aircraft did not reach the ship during the long and perilous night. Cdr. McGonagle, fortified by black coffee and assisted by relays of underway officers of the deck, remained on the bridge guiding the ship at night by observing Polaris, for the gyrocompass had been rendered useless. Ens. John Scott, Damage Control Assistant, personally surveyed the ship, monitored damage reports from his subordinates and supervised shoring of the bulkheads of the research space to prevent its collapse.

USS Davis (DD 937), flagship for Commander, Destroyer Squadron Twelve (COMDESRONTWELVE), received message traffic suggesting that the Liberty had been attacked, and the ship responded to emergency orders of Commander Sixth Fleet that she proceeded at top speed, in company with USS Massey (DD 778), to the stricken ship some 500 miles away. At first light on June 9, the destroyers found, according to Lt. (later Rear Admiral) Paul Tobin, a powerless ship covered with marks of battle damage, scorch marks, and a ten degree starboard list. “The reality of the situation struck home as we climbed aboard and looked at the faces of the men,” wrote Lt. Hubert Strachwitz of the Davis in a letter to his wife. “No Hollywood makeup man nor actor could ever produce those faces,” he went on. “There were sunken eyes, bristly, dirty faces dark bloodstains, ripped clothes covered with oil and charcoal. There were no hysterics, no crying, no cursing—just tired bodies trying to do necessary jobs.”(4)

The major evolutions required were providing medical care for the wounded, removing the dead, restoring power and stability to the ship, so that the ship could reach a safe port. Capt. Harold Leahy, COMDESRON TWELVE, came aboard and climbed to the shattered bridge where the commodore gently offered to take command of the Liberty. After consulting with Dr. Kiepfer and Dr. Peter Flynn, a general surgeon airlifted to Massey from USS America (CVA 66), he chose not to with the understanding that the captain lay below to rest. Kiepfer opined then as he did later to the board of inquiry, that Capt. McGonagle was a key ingredient—a rock upon which the rest of the men supported themselves—in the survival of the Liberty. In so doing, he had earned the right to bring her safely into port. Lt. Tobin and Lt. Cmdr. William Pettyjohn, COMDESRONTWELVE chief of staff, came on board to give temporary assistance to the engineering force and assume the duties of executive officer.

The next pressing task was to restore power and stability to the ship. Lt. Tobin and Lt. Cmdr. Pettyjohn, together with the Liberty’s crew, augmented by engineering and damage control rates, began the daunting task. Later, Tobin observed that it was good to work with the crew, for they had detailed knowledge of the layout of the darkened ship and its equipment. He also recalled that they were infused with new energy by their newly arrived comrades.(5)

By careful study of data at hand, such as the liquid loading diagram, it was determined that the list could be corrected, and the transfer of remaining fuel to port tanks was successful. Concurrently, the propulsion plant was surveyed and electric power was gradually restored after a diesel generator was started and wiring repaired. The ship was determined to be as seaworthy as possible and it was shown that, although there was much freestanding water throughout the ship, there was sufficient righting arm to enable it to recover from rolls in heavy weather. It was thought that the keel was intact.(6)

After critical systems were restored and Liberty no longer seemed in danger of sinking, the decision was made to raise steam and make the transit to Malta, 1,000 miles away. Lt. Cmdr. Pettyjohn, acting as temporary XO, established regular steaming watches and a regular underway routine. As time elapsed, the ship’s operating systems, such as her gyroscopic compass and fire and flushing water, were restored. The restoration of lighting and ventilation had earlier brought about an improvement in morale and wellbeing. Liberty was accompanied by the ocean going tug USS Papago (ATF 160) whose crew recovered bodies that had drifted though the torpedo hole as well as classified materials. Except for one unnerving night, when the ship encountered heavy weather 150 miles from Malta, the transit was uneventful. Forward bulkheads in the vicinity of the flooded spaces warped and panted. The contents of the adjacent compartments were removed and jettisoned and additional shoring placed. The weather moderated, and on June 14, with Cdr. McGonagle on the bridge at the conn, the ship entered Grand Harbor, Valetta, Malta, with Fort Ricasoli on the port beam.

Liberty spent the mid-summer of 1967 dry docked in Malta, where the remains of those who died in the Research Department spaces were removed, and a board of inquiry under Rear Admiral Isaac S. Kidd, Jr., was convened. A new permanent XO, Lt. Cmdr. Donald L. Burson, formerly the operations officer in USS Aucilla (AO 56), a Norfolk-based fleet oiler, arrived to replace Lt. Cmdr. Philip Armstrong, who had been killed in the attack.(7) It was a period for recollection of the ordeal, decompression and relaxation, as well as poignant tasks such as writing to the survivors of those lost, undertaken in an instinctively kind, gentle way by the skipper, assisted by Ens. Patrick O’Malley. The chief engineer, Lt. George Golden, remembered that when he and the skipper went to a party, the captain expressed some reluctance to leave, and when he did return to his room, “wept.”(8) Liberty left Valetta in company with Papago and arrived at Naval Amphibious Base Little Creek on July 29, 1967.

William McGonagle, as noted, was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor on June 11, 1968, after his promotion to captain. The newspaper account of the ceremony noted that after Navy Secretary Ignatius placed the award around his neck, McGonagle “wept.”(9) Three days later, he travelled to Norfolk Naval Shipyard, where Liberty was moored, pending a decision about her future. He conferred various awards, such as silver stars and the bronze star, to surviving crew members for heroism under fire. Others had already left the command. The magnitude of the crew’s bravery is evinced by the sheer number of personal awards given after Liberty’s return: one medal of honor, two navy crosses, 11 silver stars, nine navy commendation medals, and 204 purple hearts among a crew of 294.(10)

Liberty’s final act occurred on June 28, 1968, when she was decommissioned. Under clear skies, Lt. Cmdr. Burson, who had relieved Capt. McGonagle, gave brief remarks and Capt. Charles J. Beers, commander of the Inactive Ships Maintenance Facility, read the inactivation orders, the colors were lowered, and the 83 remaining crew members left the ship. (11)

Demise of Surface Intelligence Collection

The decommissioning occurred about five months after the capture of the USS Pueblo (AGER 2) while conducting a similar intelligence gathering mission off the North Korean coast. The crew was interned under brutal conditions for nearly a year. Two such episodes so close together impaired the prestige and standing of the United States and exposed brave crews to death and extended torture. The court of inquiry on the Pueblo incident, in contrast to the Liberty board of inquiry conducted by Rear Adm. Kidd, conducted lengthy deliberations and uncovered defects in program execution, such as lack of a plan to assist the ship in the case of unanticipated emergency. The most telling flaw was the assumption that ships engaged in such sensitive operations in international waters were immune from interference. The abrupt collapse of that assumption led Navy Secretary John Chafee to set aside the recommended court martial for the Pueblo’s commanding officer and punishments for those higher in the chain of command. The AGTR and AGER programs were eliminated, and Lt. Cmdr. Burson went from being the last commanding officer of USS Liberty to also being the last commanding officer of USS Palm Beach (AGER 3), which was stricken from the Navy Register on December 1, 1969

For Many, a Catastrophe without Closure

The end of the Liberty’s short career as a “spy ship” and the denouement of much of the Navy’s surface intelligence gathering activities came about two years after the attack. In its wake, uncertainty and residual bitterness remained among former Liberty crewmembers, including Capt. McGonagle, those who conducted the investigation, and former high-ranking government officials such as Secretary of State Dean Rusk. The attack was savage and repeated against key defensive and ship control/communications spaces and facilities. Liberty was much larger than the SS Quseir, the Egyptian livestock carrier for which the Israeli government concluded she had been mistaken. The question remains, why would such assets have been used against a livestock ship? The best summation of the attack was perhaps made by retired Rear Adm. Paul Tobin, who played a key role in steaming the ship to Malta. He pointed out that the Israeli attack was made against a ship that was in international waters, was freshly painted, had large, clearly painted hull beading and was adorned with sophisticated antennae. To Tobin, it was unbelievable that unsupervised pilots made repeated attacks on a defenseless ship.(12) It must be the governing evaluation until and unless the government of the State of Israel makes a truthful disclosure of the facts, as Capt. McGonagle requested in an excellent oral history conducted by former Naval History and Heritage Command historian Tim Frank, two years before McGonagle’s death in 1999.

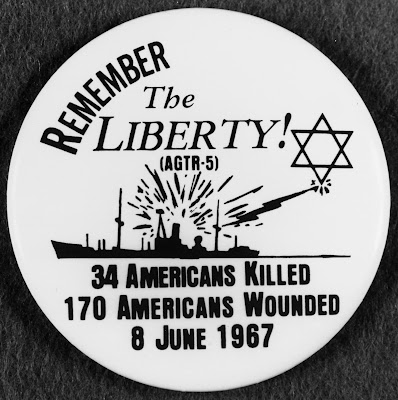

|

| A privately-produced button in the collection of the Naval History and Heritage Command. (Courtesy of Richard K. Smith, 1978) |

The attack on the ship and her brave crew and its residuals may have one overriding meaning. It is, as a Norfolk Virginian-Pilot editorial page writer opined in July, 1967, that “the arrival here today of the USS Liberty is a sobering reminder to this Navy community that no ship that clears this port is assured of returning with her hull intact and all her crewmen alive and uninjured….”(13)

Notes:

- “Liberty Skipper Gets Medal of Honor,” New York Times, June 12, 1968, 4.

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Liberty III (AGTR 5), 1964-1970

- Descriptions of the attack and its aftermath were in part taken from a tape recording of an oral presentation by Lt. Cmdr. George Golden, USN (Ret.) to an audience at the Hampton Roads Naval Museum. The tape was found and the contents abstracted by the author.

- James Scott, Attack on the Liberty (Simon and Schuster, 2009), 127.

- The order and priority of tasks that had to be accomplished are set forward in a thorough professional note written by then-Cdr. Paul Tobin, USN. This note was contained in the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings in December, 1978. Rear. Adm. Tobin shared further details with the author in a telephone interview on April 6, 2017.

- Telephone interview with Rear Adm. Paul Tobin by the author, April 6, 2017.

- In an e-mail to the author Cdr. Burson noted that his tour was a “learning experience.”

- See Note 3.

- See Note 1.

- “Retiring ‘Liberty,’ But Mostly Her Men, Honored,” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, June 15, 1968, 7.

- “‘Liberty’ Flag Lowered,” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, June 29, 1968, 13.

- The Liberty Incident: The 1967 Israeli Attack on the U.S. Spy Ship, Book Review by Rear Adm. Paul Tobin, USN (Ret), U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, August 2002.

- “Welcome Liberty,” editorial, Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, July 29, 1967, 8.

About the author: Captain Alexander “Sandy” Monroe, a retired surface warfare officer, is the author of official histories on U.S. Atlantic Command counternarcotic operational assistance to civilian law enforcement agencies and the treatment of Haitian asylum seekers at Naval Station Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. He was also dispatched to the Arabian Gulf on assignment for the director of naval history during Operation Earnest Will.