What makes men gravitate toward war? War is, after all, the most horrific of all human pursuits. Killing a lazy Saturday afternoon behind my favorite black rifle perforating paper or ringing steel is pure unfiltered recreation. By contrast, kicking in the door of a mud house dirty with tooled-up ISIS fanatics at three in the morning would be fairly horrifying. Given the obligatory terror, deprivation, physical pain, and emotional suffering concomitant with modern combat, why on earth would anyone do it willingly?

That’s a thorny question. There are roughly 20,000 foreigners fighting in and for Ukraine as I type these words. They make up seven full battalions. I’m told most hail from the US, the UK, and Georgia (the country, not the state). Their respective nations warned these insanely brave adventurers not to do this. In the event of capture, they have literally zero support. Yet they went anyway.

We humans do seem quick to embrace a proper crusade. In Ukraine, the Bad Guys are very, very bad, while the Good Guys seem pretty decent. We’re all going to die of something. It might as well be something that matters.

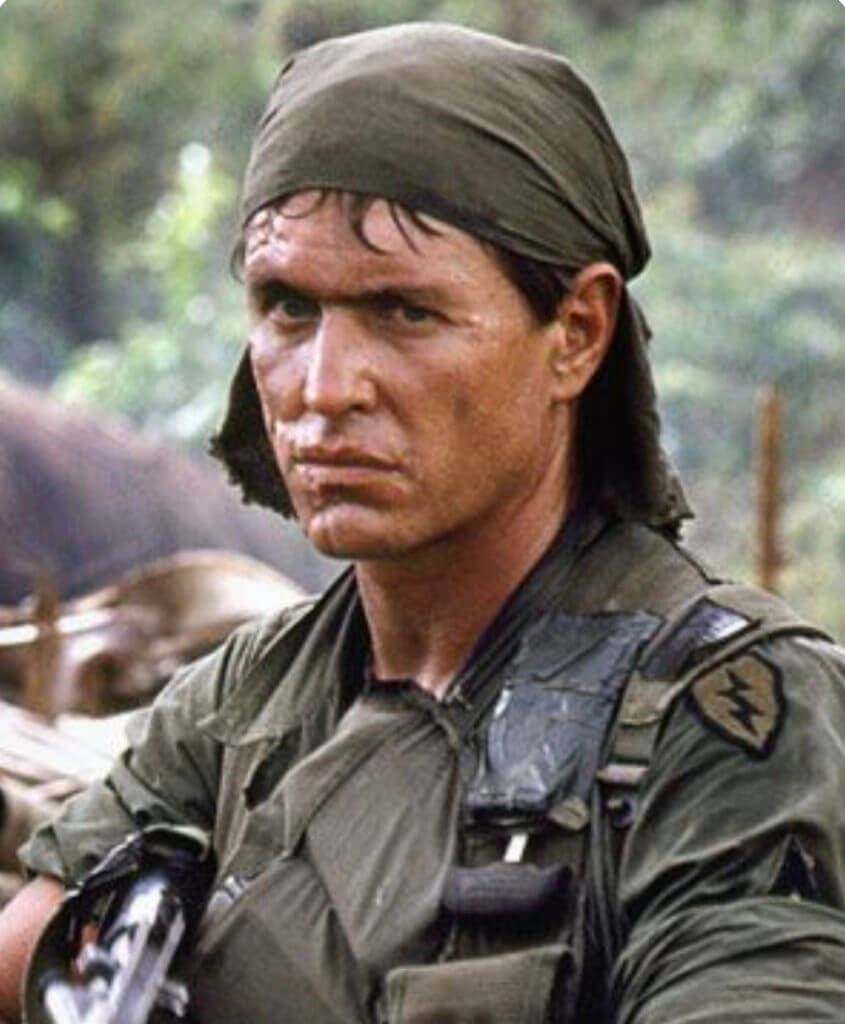

On a certain visceral level, however, some folks are just addicted to the rush. SSG Barnes from the movie Platoon is the archetype. Once Barnes discovers that war is his calling he just cannot get enough.

I served with a guy like that back in the day. He did three combat tours in Vietnam and found it difficult to thrive away from a war zone. He was forced to retire with more than 30 years of service after beating the crap out of four MPs at once. He succumbed to a brain tumor shortly thereafter.

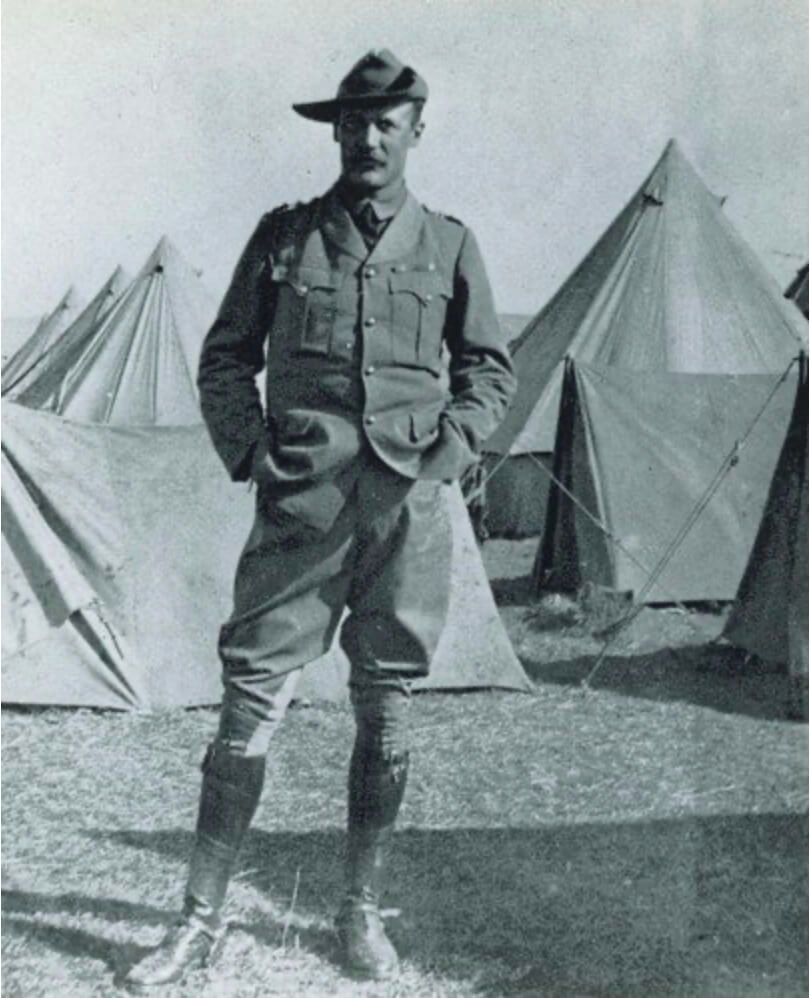

Today we will explore the extraordinary life of Ivor Thord-Gray. Thord-Gray was a combat addict. While history and his own memoires might have embellished his experiences somewhat, the places he went and the things he did are amply impressive even when viewed through that lens. His journey began in Stockholm, Sweden.

Origin Story

Ivor Thord-Gray was born Thord Ivar Hallström on April 17, 1878. The reasons he changed his name at some point have been lost to history. Ivor was the second son of a primary school teacher named August Hallström and his wife Hilda. He came from gifted stock.

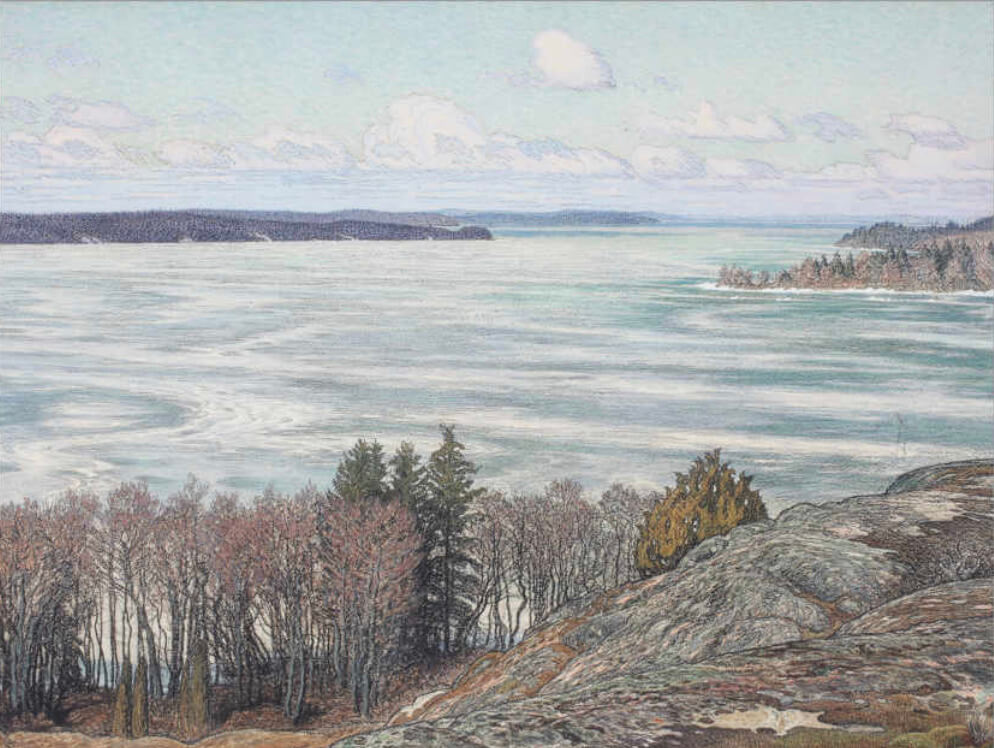

Ivor’s older brother was the esteemed artist Gunnar August Hallström. His baby brother was an accomplished archaeologist named Gustaf. By all accounts, Ivor’s upbringing was typical for his geography and his era. However, from an early age, young Ivor was found to suffer from a most deplorable wanderlust.

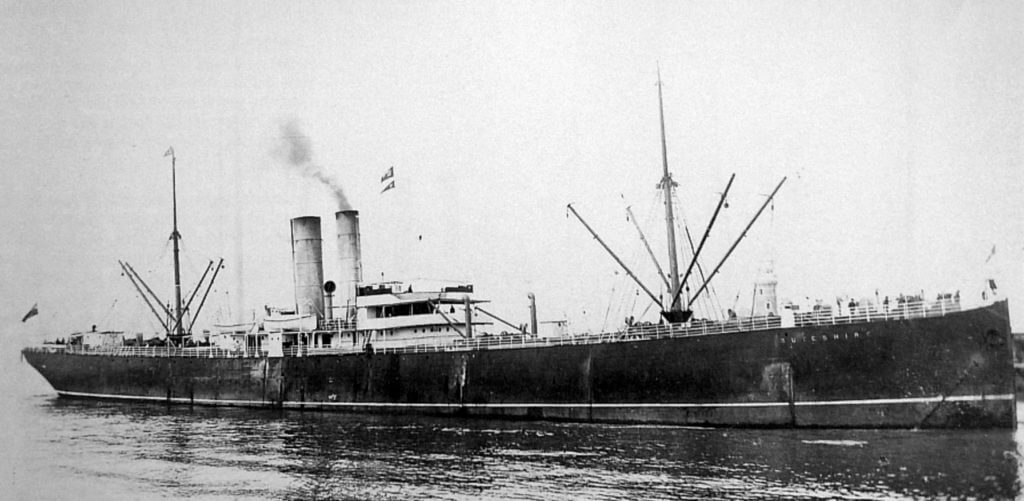

In 1893 at the age of fifteen Thord-Gray enlisted in the Merchant Marine in pursuit of adventure. For the next two years he sailed aboard three ships and explored the world. In 1895 at age seventeen he left the service to settle in Cape Town, South Africa.

Things Get Salty

In 1896 at age 18 Ivor took a job as a prison guard at the South African prison on Robben Island. I obviously wasn’t there, but I rather suspect the young man got to meet some fascinating personalities in that job. While working at the prison Ivor became both a master fencer and a world-champion archer. The following year Ivor Thord-Gray thought he might try his hand at soldiering.

Over the course of the next decade, Ivor Thord-Gray fought in five conflicts. The first and last were under the Union Jack. One stint was served alongside the Germans.

Thord-Gray first fought as a Private soldier with the Cape Mounted Riflemen during the Boer War. As a native Swede, the argument could be made he really didn’t have a dog in that fight. However, this was his first taste of proper war, and he found he had a knack for it.

With the formalized violence abating, Thord-Gray found that the weight of a pistol on his belt suited him. He therefore signed on with the South African Constabulary and served as a policeman from 1902 through 1903. During his time in the Boer War and the South African Constabulary, Ivor served as an instructor in the care and feeding of the Maxim machine gun.

Following a brief period in the Transvaal Civil Service, Ivor joined the German Schutztruppe of European volunteers fighting in Africa. During this time he would have at least touched the Namaqua and Herero genocides, the first such travesties of the 20th century in which some 80,000 people perished.

He later joined the Lydenburg Militia, this time as an officer. He fought through the Bambatha Zulu Rebellion as a Lieutenant in Royston’s Horse. He battled the Zulus at Mome Gorge where between 3,000 and 4,000 African warriors fell in battle. During this gory fight, Thord-Gray commanded a battery of Maxim machine guns. The resulting contest between assegai spears and belt-fed machineguns was a proper slaughter.

There followed a year as a Captain of the Nairobi Mounted Police in Kenya before Thord-Gray grew dissatisfied with the available chaos on the African continent. After an unsuccessful effort to join the Kaiser’s forces fighting in Morocco, Thord-Gray migrated to the Philippines to become part of the US Foreign Legion. By now he was serving as a Captain with the Philippine Constabulary. He was at this point in our tale 30 years old and had already carried a gun under more flags than I can reasonably catalog. It turned out he was just getting started.

Sundry Bush Wars

Ivor tried his hand at farming in Malaya for a couple of years but soon grew bored with it. He joined the French Foreign Legion in the Tonkin Protectorate of North Vietnam in 1909 and fought in Hoang Hoa Tham’s rebellion. He spent 1911 fighting alongside the Italians as they forcibly evicted the Ottomans from Tripoli. By 1913 he was fighting in the Chinese Revolution.

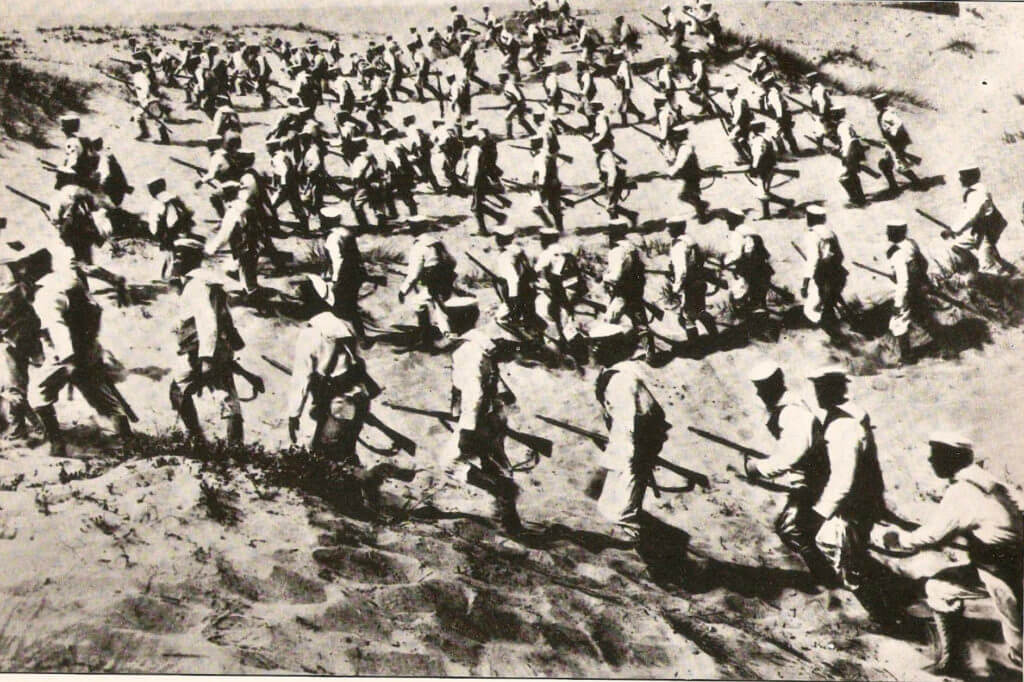

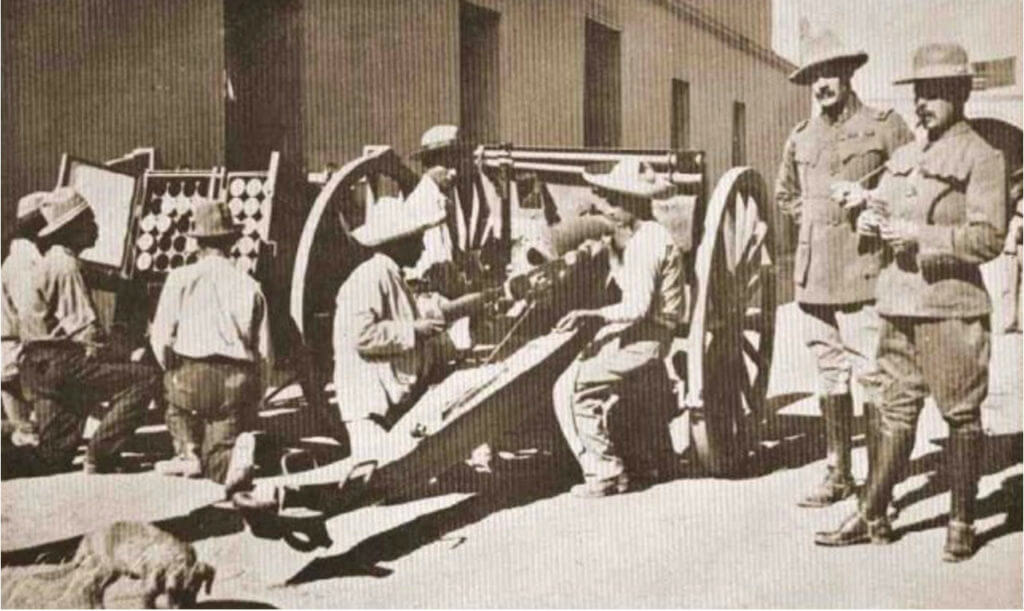

From China, Ivor sailed to Mexico to offer his now-extensive martial expertise to Pancho Villa. In short order, he had been appointed a Captain in Villa’s army in charge of the revolutionary’s artillery. At this time Villa and his rebels were supported by the United States against the Huerta political regime, though Uncle Sam obviously soured on Villa in fairly short order.

Ivor repaired disabled guns and smuggled weapons from the United States. Over the next twelve months, he quickly rose through the ranks to Colonel. He ultimately served as Chief of Staff of the 1st Mexican Army. However, it turned out all this was simply preparation for the Main Event. Back in Europe, things were heating up fast.

The First War to End All Wars

The British Army was a growth industry in 1914, so Ivor Thord-Gray signed up. His extensive military history secured him the rank of Major in the King’s service. You recall Thord-Gray was still technically Swedish.

Within a year he was the commander of the 11th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers. In late August 1914, Thord-Gray and his Fusiliers landed in France ready to scrap. Two weeks later they were on the front line. Before the war finally wrapped up, Thord-Gray had grievously offended his British commanders but had also been awarded the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal, and the Allied Victory Medal.

After the armistice he wrote the Military Secretary at the War Office as follows, “Would you kindly inform me whether you have any objection to my offering my sword to France, Belgium, or Serbia.” Throughout it all there was a persistent allegation that Ivor Thord-Gray was actually a German spy.

Thord-Gray tried and failed to join the American Army and settled for Canada instead. He served for a time as Inspector of the Imperial Munitions Board in Montreal. He eventually deployed as part of the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force to fight in the Russian Civil War.

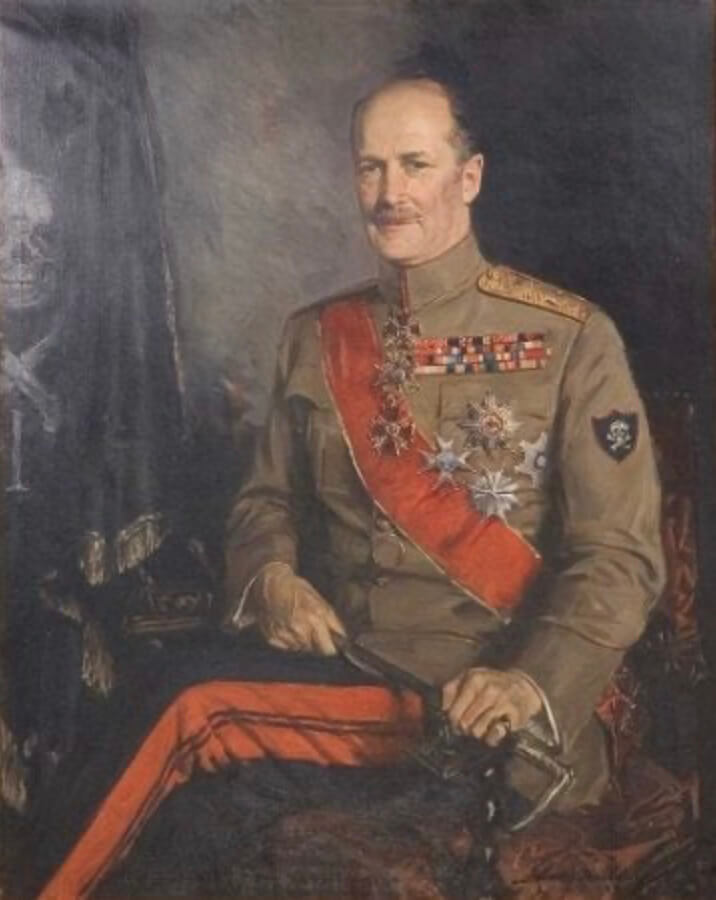

Thord-Gray transferred to the Russian “White” Army in the winter of 1919 as a Colonel serving under Admiral Alexander Kolchak. Before the year was out he was a division commander of the 1st Siberian Assault Division.

Less than a year later he was a Major General serving in the Provisional Siberian Government. One of his tasks was to sell gold reserves to foreign banks. Ivor was captured by the Soviets in the winter of 1919 with the capitulation of Vladivostok but successfully concealed the gold receipts in his pocket. One was valued at $146,946, a king’s ransom at the time. With the Communists clearly in their ascendency, Thord-Gray thought he’d just hang onto the cash.

The Golden Years

Finally in 1923 at the age of 45, Ivor Thord-Gray was ready for a break. He returned to Sweden, the country of his birth, and penned a popular tome on Mexican archaeology. Two years later he emigrated to the US and started an investment bank under the flag I.T. Gray and Co in New York City. He used the pilfered Russian gold money as a seed for his new banking endeavor.

Thord-Gray’s final mercenary foray saw him serving as a Lieutenant-General in the Army of Venezuela in 1928. While there he fought the dictator General Juan Vicente Gomez but lost. He then returned to Sweden yet again and, in his free time, earned his Ph.D. from Uppsala University.

Getting rich in America suited the man. By 1934 he was married and had two children. He settled with his family in Greenwich, Connecticut. In the summer of 1935 Thord-Gray was appointed Major General and Chief of Staff to Florida Governor David Scholtz. By 1942 his primary mission was counter-espionage in Florida.

In his declining years, Ivor Thord-Gray wrote fairly prolifically using his many-splendored exploits as grist for his typewriter. He was ultimately kind-of married five times and penned seven books.

His most popular work was titled Gringo Rebel: Mexico 1913-1914, a tome relating his experiences fighting in the Mexican-American War. Thord-Gray eventually established a winter home in Coral Gables, Florida.

By the end of his life, Thord-Gray had thrived through fully six careers as a sailor, soldier, ethnologist, linguist, investor, and commercial writer. He served in ten identifiable armies across sixteen wars. This remarkable man peacefully shuffled off this mortal coil in the summer of 1964 at the age of 88. His extraordinary life was that of the archetypal war junkie.