Two guns exemplified changing technology in the 1870s, if not consumer tastes. The Sharps Model 1878

Borchardt was one of the last single-shot rifles offered to a world military establishment newly focused on

repeating rifles, and the Colt Model 1878 combined the quaint technology of the Single Action Army’s extraction

with the rapid fire of a double-action combat revolver.

A funny thing happened in 1878. A sleek, futuristic single-shot rifle offering breeching strength beyond the needs of the day’s cartridges debuted just as the repeating rifle was brushing them aside in military and civilian arms decisions. Then a large-frame double-action revolver presaged the next 100 years of outdoorsman’s arms by cleverly combining old dependable technology with refreshing new concepts of combat firepower. The former witnessed the end of the Sharps Rifle Co., while the latter was another step in the continuing dominance of the Colt Patent Firearms Co. into the 20th century.

By the time the Sharps Model of 1878 was presented to the world’s militaries, the end of the single-shot rifle as a military arm was in progress, closely followed by civilian preferences. Scottish-born American inventor James Paris Lee’s turn-bolt with a detachable box magazine was turning heads and would become the famously successful Lee Enfield. The Lee rifle was unable to save the Sharps Rifle Co. from bankruptcy, the company Lee initially chose as manufacturer. Elsewhere, European militaries were developing or had repeating rifles in service.

On the civilian side, Eli Whitney and Andrew Burgess heralded the big-bore lever action with the Model 1878 Burgess in .45-70 Gov’t. Although it was a dud, Andrew Burgess’s next invention — the Marlin Model 1881 in .45-70 — really set the American hunting scene on fire, further marginalizing the single shot.

The Sharps Borchardt

Hugo Borchardt, shop foreman for the Sharps Rifle Co., brought forth one of the last, best single-shot rifles of the 19th century. In military guise, the Model 1878 was sold first to China (in 1876 — like the 74 Sharps, the company had them in production before giving them a name), but the door was closing for a single shot, despite domestic sales to a variety of state militias and the odd police force.

What made the rifle a great military arm was strength, simplicity and safety. The manual of arms was easy to learn due to the hammerless design and automatic safety. Opening the vertically sliding breechblock engaged a trigger-shaped safety just behind the trigger. Taking the safety off was done naturally by the trigger finger, which then moved forward to squeeze the trigger. U-shaped, the safety could be pushed forward to re-engage.

Lowering the breechblock also cocked the action and extracted the spent cartridge to be plucked out, leaving an open trough for the next one. Striker fired, ignition of the cartridge was fast and sure. Besides great breeching strength (it has been lauded as the era’s fifth strongest single-shot action) and fast locktime, the Borchardt had one other feature endearing it to riflemen.

A horizontal bolt running through the stock gave the rifle greater stability than the use of screws running vertically through top and bottom tangs used by most other rifles. Those rifles suffered accuracy problems as the wood shrank and swelled, something mitigated by the stock through-bolt. These attributes would turn the Borchardt into one of those “Holy Grail” rifles of the varmint shooter until well after World War II.

With military sales tepid, the company began offering the new rifle to target shooters and hunters. For target shooters, the much lighter action meant more weight could be put into the barrel where it improved hold and performance while still making weight set by NRA rules. Hunters, by nature traditionalists, were scandalized by the lack of a hammer and lack of double-set triggers.

The military trigger with its heavy, creepy letoff was tuned acceptably for the target and hunting models, but Borchardt’s efforts to create a suitable set trigger proved problematic, and something never quite solved to anyone’s satisfaction. Since set triggers weren’t allowed in Mid- or Long-Range matches under NRA rules, the tuned single trigger served well. The round barrel seen on most Borchardts was lauded by Sharps as stronger and more accurate than octagon or half-octagon configurations.

The Sharps Rifle Co. offered the Model 1878 to the general shooting public in a bewildering array of models and options. Hunting rifles came in most Sharps calibers and almost every conceivable receiver configuration, barrel length and weight. The receiver was left in the flat-side, clumsy military style, profiled elegantly above and below the receiver ring for the target and some hunting models, octagon topped to match the optional octagon barrel and almost any combination of those. Target models were often lightened further by milling recesses at the back of the receiver, and the recesses filled with panels of hard rubber, wood, horn or other exotic materials.

Hands-On

Our Model 1878 Sporting Rifle has a 30″ round barrel in .45-70 Gov’t with the elegant target model sculpting to the front of the receiver and a weight of 10 lbs. The top tang is drilled and tapped for an external tang sight, which was never added. (Target models had a removable tang for the very precise Borchardt tang sight.) This rifle’s sights consist of simple carbine-style ladder sight with fine notch and a picayune German silver front. The sights are exceptionally hard to see for any but very sharp eyes. The barrel has a 1:20″ twist with shallow rifling. The gun was well cared for and the rifling sharp, with just a hint of erosion in the throat.

The rifle is still capable of good accuracy, and a 3-shot, 100-yard group of 1 1/8″ was the best achieved, although requiring utmost concentration. Most of my 3-shot groups are in the 2″ to 2 1/2″ range. The trigger pull is a little spongy, but lets off just under 3 lbs. At 10 lbs. with a flat, checkered steel buttplate, recoil is very manageable even with 500-gr. bullets over black powder.

The rifle doesn’t shoot smokeless loads well. The firing pin and hole are very large, and even modest loads cause primers to set back and flow into the firing pin hole enough that lowering the breechblock is difficult. This never occurs with black powder loads. One of the first things a 20th century gunsmith would do is bush the firing pin hole for a small firing pin.

Factory records are incomplete and it is estimated fewer than 9,000 or up to 22,000 were made, depending on the source, with the majority military models. The Sharps Model of 1878 scandalized the day’s buyers with its lack of a big hammer, but its timeless good looks and performance attributes were welcomed by discriminating riflemen in the 20th century.

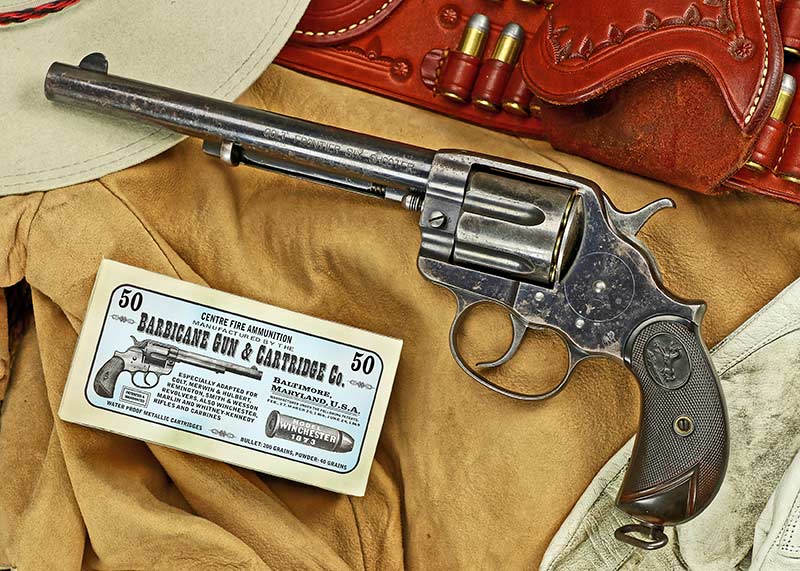

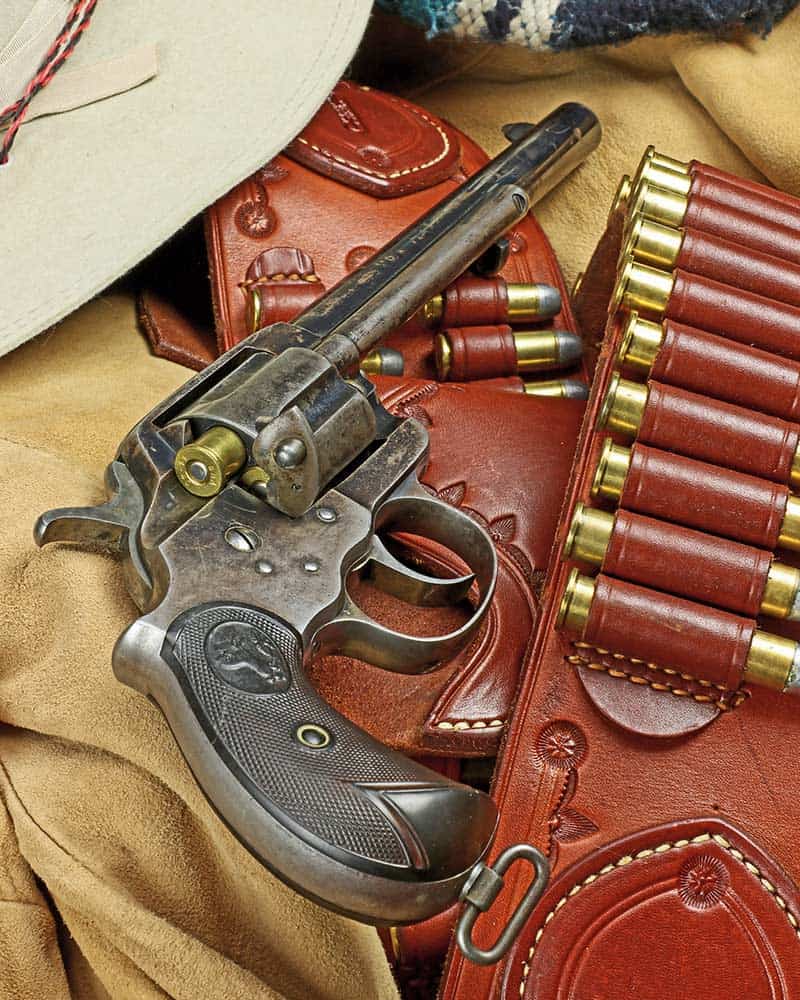

The Colt Model 1878 Revolver

Big, homely and ungainly, the Colt Double Action Model of 1878, nicknamed “Omnipotent” by mid-Western dealer B. Kittredge & Co., never achieved the success of its venerated older brother, the Single Action Army. Featuring a robust action, the 78 shared the front end of the SAA, shot equally as well, but only 51,210 of the big revolvers were made in the 29 years they were offered.

Double-action revolver systems of yesteryear never compare well with those made in the 20th century. It is very difficult to hit well shooting one of them double action. The DA pull was meant for close quarters where aim didn’t have to be precise. If there was time and room, only single-action aimed fire ensured hits.

The smaller, handier Colt Model 1877 in .38 or .41 Colt was vastly preferred for power and portability over the large 1878, although its action was more fragile. Those in favor of large-bore handguns preferred the single action, as did target shooters. Overseas, the double-action mechanism was preferred and had been in ascendancy since before the American Civil War. Percentagewise, more Model 1878 revolvers than Single Actions were made in British calibers, and it was modestly popular as an officer’s private purchase.

The arm shared the same barrel lengths and calibers offered in the Single Action Army, simplifying things for Colt. The cylinders are the same length and circumference, but use a shorter bushing and have no bolt notches. While not interchangeable with the SAA, Colt modified them for SAA revolvers in the pre-WWI era. These revolvers can be quickly identified by their “long flute” cylinders. Only made for a few years to use up 1878 cylinders on hand, they sell at a premium today.

The puny-looking “bird’s beak” grip feels pretty good even to large hands. The first ones had a larger grip of the same style and looked more proportional, but few could reach the trigger comfortably, so the grip was reduced in size. A knuckle at the top of the grip prevents the revolver from rotating up in the hand at discharge like the SAA. Firing full-throated black-powder loads in the larger calibers delivers a sharp rebuke to the web of the hand.

Colt added a new transverse locking system to ease removal of the cylinder for cleaning, something the SAA wouldn’t get for another couple of decades. Build and finish quality are up to Colt’s usual high standards, with most found fully blued or nickeled. Balance is good and the gun points naturally. The hammer is easily reached for thumb cocking, and the single-action pull light. The double-action pull is long, heavy and clunky.

Oddly, the sideplate/hammer screw has a reverse thread. Many a greenhorn has honked on this screw ruining it beyond redemption. Otherwise, the internals are few in number, large and robust. When fully disassembled, the amazing thing is the intricate machining involved in their manufacture, and better appreciated once you show them to a machinist. It is not unusual to find these revolvers working fine after all these years.

The cylinder locking is done entirely by the hand, since there is no cylinder bolt. That’s a lot of work for such a small part, and lock up is often loose if the revolver has been shot much. The hand spring is weak as well. Another issue is a mainspring is a little too heavy for a comfortable double-action pull and barely capable of popping the day’s primers reliably.

With almost all simultaneous ejection systems under patent worldwide, and the swing-out cylinder yet undiscovered, the 1878 broke no new ground in this respect. Its novel double-action system was saddled with Colt’s single-action loading/ejection system. Anyone familiar with the SAA will find the manual of arms similar. Pulling back the hammer to the first or second notch moves the hammer nose out of the frame window.

Opening the loading gate then allows the cylinder to be charged or the empties punched out with the SAA-style ejector. The hammer must be fully cocked before lowering on an empty chamber. Left in either safety notch, the cylinder easily rotates, so like the SAA, the 1878 should only be carried with five rounds and the hammer lowered on an empty chamber.

A Unique Take

Which brings us to the most peculiar attribute of the design. With no cylinder bolt like the SAA, once the trigger is released, the hand goes out of battery, and the cylinder is free to rotate. It will counter rotate one chamber but for a small projection added to the loading gate. As the cylinder rotates, the loading gate moves very slightly out of position to pass the cylinder then drops back to prevent the cylinder from rotating backward.

It looks as funny as it sounds, but it wasn’t really a problem during use because the non-rebounding hammer stays buried in the spent primer. It would only look bad in the showroom and, of course, that’s not the place to stumble. The gate’s tab offers another benefit in that it retards the cylinder from rotating if the hammer is left in the safety notch instead of down on an empty chamber. Not as foolproof, but safer than if the cylinder was spinning free as with many other revolvers.

Today, the Colt 1878’s never sell for as much as the SAA on the collector market. Seventy-Eights in original condition get truly rarer every year, since too many unscrupulous dealers scavenge gun shows even today and dismantle pristine ones for their barrels, “restoring” Colt SAAs to enhance their value, then bartering off the poor 78’s carcass to other dealers for parts or nominal restoration. Alas, too many nice, original revolvers have met this fate.

Colt’s next big-bore handgun — the New Service — used the “swing-out” cylinder offering simultaneous extraction, and proved a resounding success. The big revolver found its way to the hips of many an outdoorsman, soldier and police officer. The Model of 1878 filled a necessary gap until then, and ably served around the world in the same roles.