Britain Stands Alone

Between May 26 and June 4, 1940, more than 330,000 British, French, Belgian, Dutch, and Polish troops were evacuated from the beaches at Dunkirk. By June 25th, another 190,000 troops (more than 140,000 of them British) were evacuated to England from French ports. Unfortunately for the British Expeditionary Force, they left their heavy weapons and vehicles behind. Most of the troops who made it to England arrived with just the uniforms on their backs, their rifles and machine guns having been abandoned in France.

With France conquered, the Germans began bombing England in earnest by the middle of July. Initial attacks were on merchant shipping in the Channel, followed by ever increasing raids on British radar installations and RAF fighter fields across southeastern England. As more and more German aircraft appeared over the British Isles, the prospect of a Nazi invasion seemed more likely every day, particularly an aerial assault by German paratroops. By the end of the first week in September, hundreds of German bombers were attacking London by day and night. England was in grave danger.

Help From America

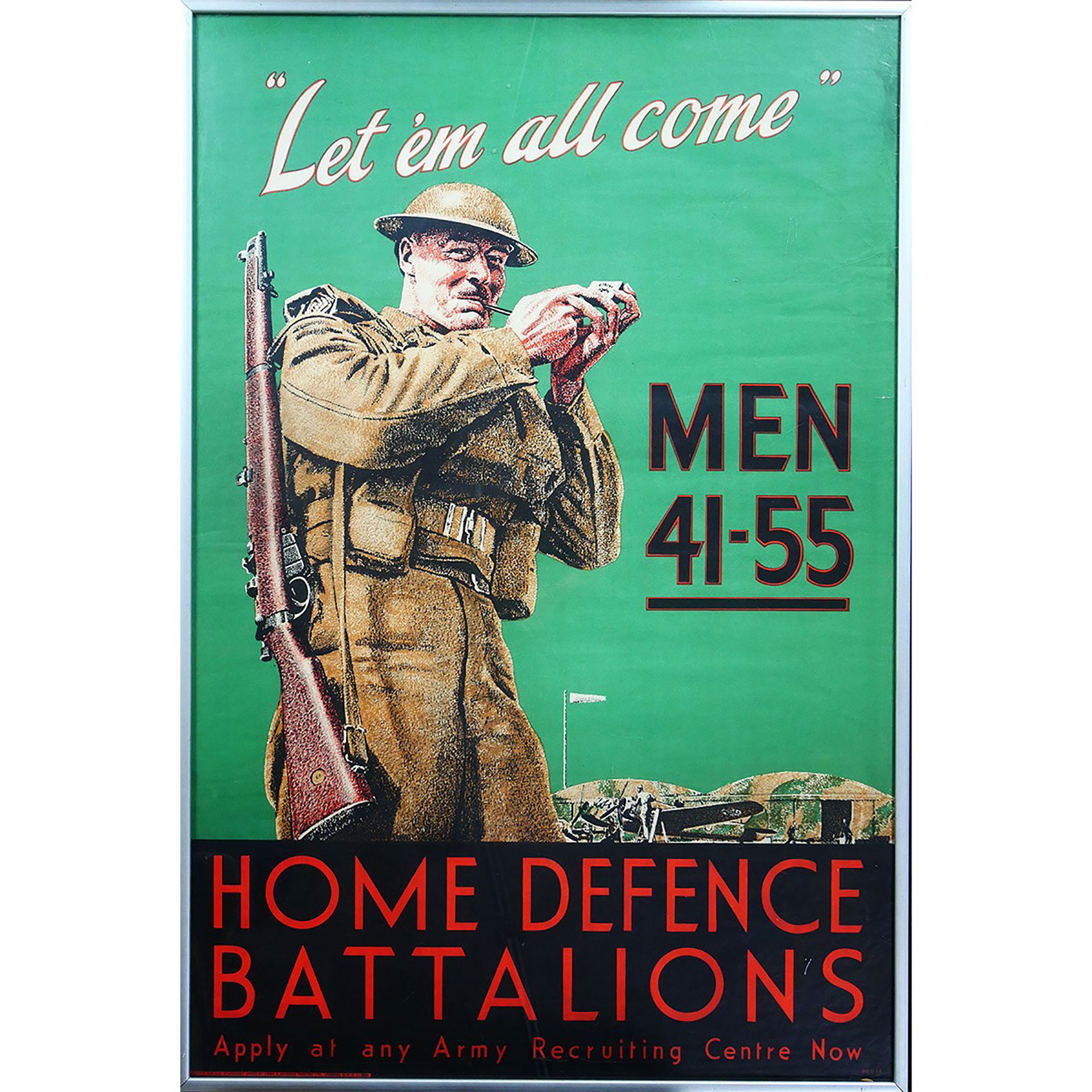

While RAF fighters struggled to defend their airspace, the British Home Guard did their best to mobilize a legitimate militia to help defend against a German invasion. Small arms were particularly scarce. There was no lack of volunteers, but unarmed free men would do little to stop well-armed Nazi wolves at the door. America, though still neutral, was quick to help. By the autumn of 1940, the American Committee for the Defense of British Homes was formed (with key organizational assistance from many NRA members).

Appeals were presented to American citizens in many publications (including, of course, American Rifleman magazine) to help the British defend themselves. Pistols, rifles, shotguns, and binoculars were collected from generous Americans and shipped to England. In December 1940, President Roosevelt described the concept of turning America into The Arsenal of Democracy. On March 11, 1941, the critical Lend-Lease Act was signed into law, and arms began to flow from America to England. Winston Churchill later wrote: “By the end of July 1941, we were an armed nation.”

A wide range of US military firearms were sent to England, predominately for use with the Home Guard. The biggest challenge for the British was that most of these arms were chambered in .30-’06 Sprg., or in .45 ACP.

The M1917 .45-cal. Revolver: The British Army had adopted the M1917 revolver during World War I, and many remained in British stocks. More came over in Lend-Lease, and these were used by the Home Guard and also by the Royal Navy.

The M1917 & P14 Rifles: During 1940-1941, the British acquired 734,000 of the “United States Rifle, Caliber .30, Model of 1917“. These were marked with a highly visible red stripe painted on the fore-end of the stock to distinguish between the American M1917 and the British P14 chambered in .303 Brit.

The Browning M1917 Machine Gun & The Colt-Vickers M1915 Machine Gun: The Browning M1917 .30-cal. water-cooled machine gun was supplied to England during the early days of Lend-Lease, with about 650 guns going directly to the Home Guard. The US Colt-Vickers M1915 was of more value to the Home Guard, as it differed only in caliber from the standard British heavy machine gun. Approximately 7,000 M1915 MGs were provided to the Home Guard and served until they were destroyed post-war.

The Browning Automatic Rifle: The British were quite impressed with the BAR, and they strongly considered the weapon (in .303) until 1930, when they decided to move forward with the Bren Gun design. After the BEF abandoned most of their heavy weapons in France during late May 1940, there were only about 3,000 Bren Guns left in England (almost 27,000 having been lost in France). To compensate, the British acquired about 25,000 BARs, and these served the Home Guard until the end of the war. There was much concern in England about Home Guard BAR gunners “wasting ammunition” by using the weapon set for full-auto fire. After 1943, the Home Guard was instructed to use the BAR strictly in the semi-automatic mode.

The Thompson Submachine Gun: The Thompson submachine gun was the most numerous American-made firearm supplied to the Home Guard, and ultimately to British forces throughout the war. The “Tommy Gun” made a huge impression on the British, from Prime Minister Winston Churchill to the man on the street and boys in the schoolyard. Even before Lend Lease in March 1941, the British had purchased 108,000 M1928 Thompson Guns from Auto Ordnance. By the end of the war, America sent a little more than 650,000 Thompson Guns (of all models) to England.

The Home Guard Remembered

It is difficult for us to understand now the precarious situation in Britain was in then. As a researcher, I can work to uncover the details about firearms sent and used. I can write about strategy and tactics. But I wasn’t there, and I don’t know how it felt. In that light, I was fortunate to have a friend who lived through the Battle of Britain as a pre-teen boy. I asked Gerry Marsh if he would share his memories of those days and his observations of the Home Guard in his community.

I recall listening to a radio broadcast encouraging those able to join a defense group to do so, to report to their local police station and sign up for duty. I recall, too, for the figures are lodged in my head with pride, the government fully expected half a million men and women to sign up. In fact, 1.7 million volunteered. What did they get for that? Eventually they received a uniform, even later a rifle, along with hours of arduous duty without pay, and the undying gratitude of a whole nation for men and women torn from their placid lives and pressed into service in a national emergency.

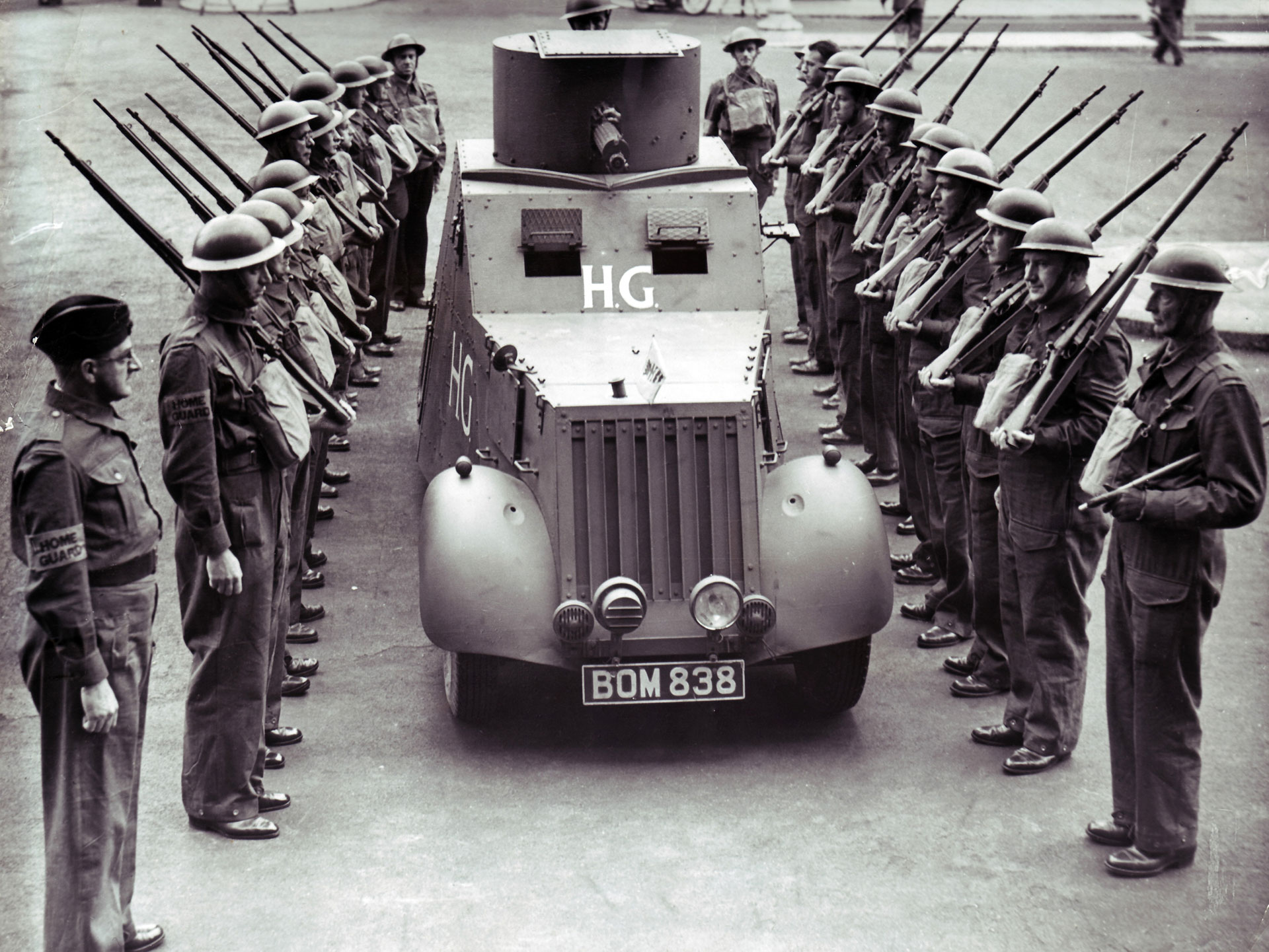

The group I watched was one of the many that sprang up quickly and spontaneously, inspired by other patriotic groups that had gathered themselves in anticipation of invasion. They would morph into the Home Guard when that body was approved by, and subject to the rules of, the Home Secretary. The group I saw was all male, for women did not join them until the Home Guard was approved and regulated by Whitehall’s Home Office.

Many of the volunteers in my group, particularly the older ones, must have wearied at the thought of new danger, a renewal of a hell they thought was over. World War One had ended only twenty-nine years before, in 1918. It was still fresh in their minds and in the minds of my parents and grandparents. I thought then, and I think now, that World War I and World War II were for all practical purposes one war with a short tea break.

The playground, or the Bullring as we called it, was solidly edged with subsidized housing, or what we called council houses, built close together, surrounding the playground unbroken, save for three narrow entrances. On the playground was a roundabout and a quadruple set of swings. The paint on them had worn off years ago. The ground was hard packed and stony and bearing occasional stretches of determined grass. It was on one of these patches that the Home Guard assembled for training.

The men wore ordinary clothes. A few were in the suits they wore to their offices in town, others wore work clothes suitable for their jobs in a butcher’s shop or the barber’s, while many of those who worked on the land wore rough linen shirts without collars, heavy muddy Wellington boots and baggy pants of a hard wearing material, none-too-clean, tied up just above the knee with a bit of frayed string. There was a little laughter, but not much; this was a serious business. Any time, today, tomorrow, or who knows when, German Junkers Ju-52s could fill the skies and drop heavily armed parachutists in our midst.

These men, who should have been at home before a coal fire, reading the Daily Mail and looking forward to dinner were instead out on this cold night, ready to defend their country. They were in a serious mood, occasionally jocular in the British manner, but they were there to learn. There was no telling when they might need the deadly skills they were taught.

Several of the men, farmers from around Chester, had shotguns. Three or four of the men had Enfield bolt-action rifles left over from WWI. Three or four had ancient pistols, guns they were apparently allowed to keep when World War I ended. An unfortunate few had only broomhandles sawn down to shotgun size. They all wore armbands, brown bits of cloth on the left upper arm bearing black letters. The early groups called themselves different things, “D.F.” for Defense Force, “P.A.” for People’s Army, and similar names until the government set about organizing them. The man in charge had sewn on just above just below his armband, a design of three V-stripes denoting his rank as Sergeant.

I cannot remember exactly what the Sergeant said; I recall only that he stressed upon them the importance of what they were doing and told them he had every hope that the government would be able to furnish them all with uniforms and guns in the future. Rifles were slow in coming. I remember that later, to compensate for the paucity of guns and ammo, they were taught how to make improvised hand grenades and Molotov cocktails.

I think that they trained four nights a week. It was not their only chore. Later in the evening, when it was dark, I would see some of those same men, in pairs, patrolling the streets, doing double duty, this time wearing a different band on their sleeve, “A.R.P.” or Air Raid Precautions. Their job was to make sure all lights were hidden by drawn blackout curtains. People walking in the street were told to put out cigarettes with the unlikely warning that Luftwaffe pilots could see the end of a lighted cigarette from six thousand feet up.

If there was a raid, the HG or ARP men were to douse incendiary bombs if possible, as they were likely to be on the spot more quickly than the fire brigade. On occasion, they would run to the site of a downed enemy plane, rescue the pilot if they could, strip him of weapons and tun him over to the police. Or perhaps kill him.

The End Of The Beginning

The Luftwaffe Blitz on British cities lasted from Sept. 7, 1940 until May 11, 1941. More than 40,000 British civilians were killed, and approximately 2 million homes were destroyed. London was devastated, but England survived. Winston Churchill had commented “We can take it”, and indeed the British could. Grit and sacrifice had seen them through the darkest days. Fears of a German invasion started to fade, and after America entered the war in December 1941, a “friendly invasion” of American troops began soon after.