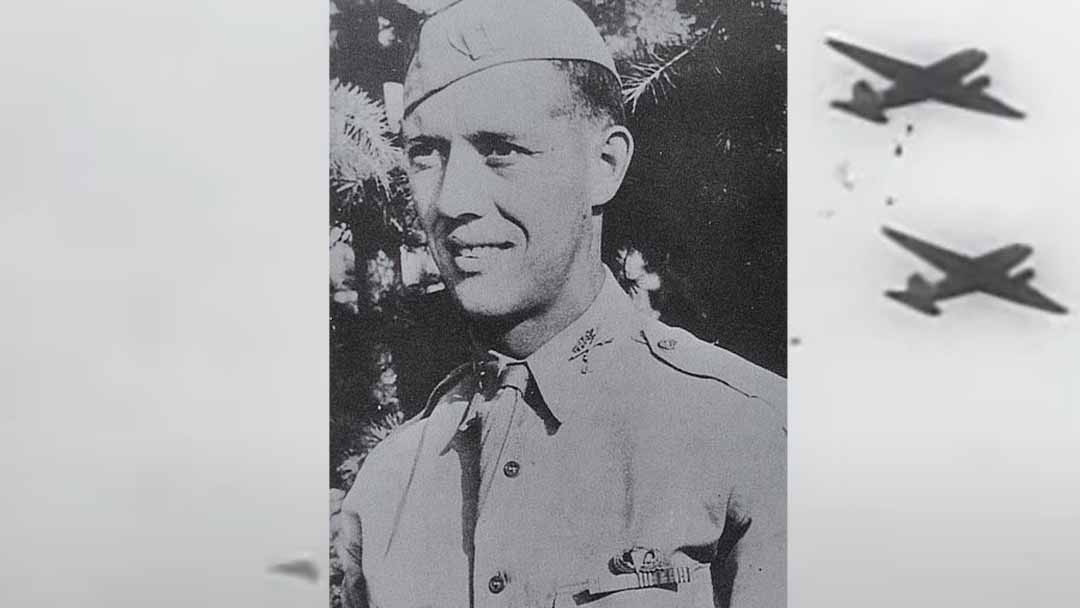

A 140 lbs. former newspaperman from New York, a cigar clenched in his teeth, was the tip of the spear for Operation Overlord.

Capt. Frank Lillyman, of the 101st Airborne’s Pathfinders, is credited as the first Allied soldier to parachute into France shortly after midnight on D-Day, June 6, 1944. He commanded the first “stick” – or unit – of Pathfinders that parachuted into Normandy, tasked with helping mark landing zones for the 13,100 paratroopers that would soon follow in the early morning darkness.

Medals, ribbons, and patches, including a Distinguished Service Cross and Purple Heart for Lillyman’s actions on D-Day, will be on offer at Rock Island Auction Company’s May 13-15 Premier Auction.

Paratrooper after Recruiter

Lillyman grew up in the Southern Tier New York town of Binghampton where he worked for the local paper covering sports and working elections before joining the army in 1934. Serving in the infantry, he was stationed in China and Hawaii before returning to New York where he served as a recruiter in Syracuse.

Lillyman longed to join the fight with the start of World War II and became a paratrooper in 1942. He made 47 training jumps before his first combat jump into the dark Normandy night.

Pathfinders needed

Following a disastrous paratroop mission in Sicily that scattered airborne soldiers over miles of terrain and limited their fighting effectiveness, it was determined that a lead force needed to be inserted that could guide the larger force to drop zones.

The Pathfinders were born.

Pathfinder missions were considered suicidal with a fatality rate of 80 to 90 percent. Many of the men who volunteered for the role were considered mavericks – insubordinates and undesirables who were trying to stay out of the brig or rehabilitate their service record.

Lillyman fit the bill, considered by at least one superior as an “arrogant smart-ass.”

While mavericks and insubordinates may not be the best in the regular army, they were just what the Pathfinders needed. That showed on June 6.

War Paint and Special Equipment

Many of the men in Lillyman’s stick put war paint on their faces for the nighttime jump. Some wore Mohawk haircuts.

The paratroopers carried special equipment to help guide the planes to the drop zones. First were the radio transponders, called Eurekas that transmitted to special receivers in the planes called Rebeccas. The Rebeccas calculated the range to the Eurekas based on the timing of the return signals and its position using a highly directional antenna. In the early hours of D-Day, Lillyman’s men placed the Eureka transmitters in a church steeple and in a tree. The second bit of special equipment were specially-designed lamps to show the jump zone.

Because of the extra equipment, many of the paratroopers ditched their reserve parachutes under their benches on the plane, going against procedure.

Might As Well Jump

Lillyman hurt his leg in training a few days prior to D-Day. He hid the injury and tried to ignore the pain so he would be able to lead his unit. He jumped with his signature unlit cigar held tightly in his teeth, carrying 70 lbs. of equipment and his Tommy gun.

“On my first jump I happened to have a cigar,” Lillyman explained. “So I’ve done it ever since. Now the boys attach a lot of importance to that cigar.”

The overcast sky troubled the plane’s pilot, missing landmarks on approach and coming in low. Lillyman and his squad missed their jump zone by about a mile, parachuting in from 450 feet. All but one of the Pathfinder units missed their jump zones that night.

Make the Best of It

When Lillyman landed he tried to determine his position. As he did, he spotted a shape off in the darkness. Was it moving toward him? He racked his gun only to find out he was targeting a cow.

Collecting his unit, Lillyman improvised a drop zone in a field deemed big and open enough. As the men set their equipment in place a machine gun barked at them in the dark. The captain sent two soldiers to take care of the nest.

The Pathfinders also reconnoitered a nearby farmhouse, learning a German officer was there. The owner pointed to where the man was asleep, a bottle of champagne on the nightstand. The soldiers dispatched the German and made off with the bubbly.

Lillyman and his men heard the planes of the main paratrooper force at 12:40 a.m., less than 30 minutes after they landed. The first plane flew over their position at 12:57 a.m. on D-Day.

The weather troubled the main force of paratroopers, too, scattering them across the peninsula. Despite the Pathfinders, only 10 percent of the U.S. airborne forces hit their drop zones and 50 percent of the troops landed one to two miles from their drop zones.

After setting up the improvised drop zone and guiding in their fellow paratroopers, they checked where reconnaissance aircraft had spotted a gun emplacement that could hammer Utah Beach. They discovered it bombed out.

Lillyman’s unit was called on to set up another drop zone but this time for the second wave of gliders. On the evening of D-Day, Lillyman’s unit waited for the gliders, code-named Keokuk, to arrive. The Germans were also waiting near the landing zone. As the gliders coasted in, the Germans opened fire.

Lillyman’s unit returned fire at the nearby German gun nest, forcing the Germans to withdraw. The captain heard one last burst of gunfire and felt the sting on his arm. He glanced down. His uniform was chewed up and blood pulsed out. His legs gave way. He fell to the ground as mortar splinters hit him in the face. His injuries would get him shipped back to England for convalescence.

Back In

After a couple days in the hospital, Lillyman was restless and ready to get back to the fight.

“I didn’t like the idea of staying in a hospital, so I found some clothes in a supply room and shoved off,” Lillyman said. “I forgot to tell anyone where I was going or what my intentions were, but after two days, I ended back here in France.”

He went absent from the hospital without permission, talked his way onto a supply ship, and by June 14 reported back to duty in France. That didn’t sit well with his commanding general who moved him to another unit. Lillyman was a pathfinder no more.

Market Garden and More

Lillyman, like his band of brothers in the 101st Airborne, still found plenty of action.

His unit jumped into the Netherlands as part of Operation Market Garden in September, 1944 fighting for roads and bridges. The 101st was caught up in the Battle of the Bulge and was “the hole in the doughnut” as the Germans laid siege to Bastogne in December, 1944. Lillyman and his comrades were pulled off the line in February, 1945.

Returned to the line in early April, Lillyman’s unit captured Berchtesgaden. As the war ended the paratroopers took up occupation duties and started training for deployment to the Pacific Theater. The war ended before the 101st Airborne could get to the Pacific.

Lillyman returned home having been wounded three times and wearing 12 decorations, including the Distinguished Service Medal for his D-Day leadership.

After The War

During a quiet moment, Lillyman wrote a fanciful letter to a New York City Hotel about his dream homecoming in October, 1945.

“I desire a suite that will face east so the sun will wake me in the morning,” he wrote. “I do not desire to know in advance what dishes will be served, but I do not want a dish repeated. If meals are served after dark in the suite, I would like tapers for table lighting. I desire a one‐way telephone—outgoing only.”

He showed up at the hotel with his wife, daughter, and $500. Hotel staff told him their stay was on the house.

Lillyman remained in the army, serving through the Korean and Vietnam Wars, holding a variety of assignments at Fort Bragg and Camp Breckenridge. He retired as a lieutenant colonel in 1968, and died three years later at the age of 55.

D-Day Medals

The Distinguished Service Cross and Purple Heart earned on D-Day as well as a Bronze Star, Belgian Croix de Guerre, and two French Croix de Guerres awarded in service to the Allied cause mark Capt. Frank Lillyman as a war hero and truly one of the Greatest Generation. Also included is a Combat Infantry badge, Master Parachutist Badge, and a scarce Pathfinder “winged torch” patch. The memorabilia available at Rock Island Auction’s May 13-15 Premier Auction shows the history and bravery of a man and his unit on D-Day, and someone who committed his life and career to the United States Army.

Sources:

`First to Jump: How the Band of Brothers Was Aided by the Brave Paratroopers of Pathfinders Company,’ by Jerome Preisler

`First in France: The World War II Pathfinder Who Led the Way on D-Day, by Alex Kershaw, historynet.com

`Skaneateles Man, Captain Frank Lillyman, the First Soldier to Land on D-Day,’ Onondaga Historical Association

`Frank Lillyman Is Dead at 55; First Paratrooper at Normandy, The New York Times

`Airlift and Airborne Operations in World War II,’ by Roger E. Bilstein, Air Force History and Museums Program