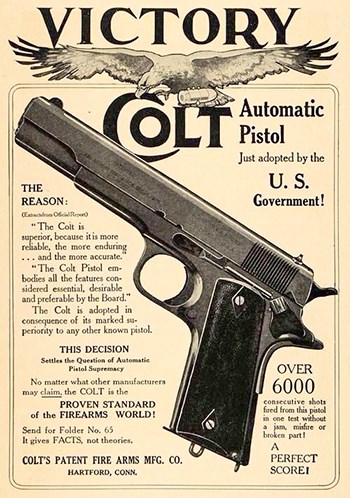

When Congress passed, and then-President Bill Clinton (D) signed, the Federal Assault Weapons Ban in 1994, semi-automatic firearms had already been popularly sold to civilians for about a century. To name one, the still highly regarded Model 1911 semi-automatic pistol served as the standard-issue sidearm for the United States Armed Forces from 1911 to 1987, and, at the same time, was and is popular with American citizens for competition and self-defense.

The AR-15, meanwhile, was hardly the first semi-automatic rifle. Many popular semi-automatic rifles were made for civilians in the first years of the 20th century by Remington Arms, Savage and others. But today, when we think of semi-automatic rifles, the AR-15 jumps to mind; the thing is, even its development and introduction isn’t popularly understood.

The AR-15, meanwhile, was hardly the first semi-automatic rifle. Many popular semi-automatic rifles were made for civilians in the first years of the 20th century by Remington Arms, Savage and others. But today, when we think of semi-automatic rifles, the AR-15 jumps to mind; the thing is, even its development and introduction isn’t popularly understood.

After years of development, in 1963, the U.S. military finally ordered 85,000 AR-15s for the Army and 19,000 for the Air Force. On July 1, 1964, the U.S. military ceased production of the semi-automatic M14. Soon the similar looking but very different full-auto military version of the AR-15 was dubbed the M16. It would become the iconic gun of the Vietnam War.

When this happened, Colt had already begun selling semi-automatic AR-15s to U.S. consumers, starting in 1963. The November 1964 issue of American Rifleman reported, “A semi-automatic model of the Colt AR-15 cal. .223 (5.56 mm.) automatic rifle is now offered by Colt’s. Designated Colt AR-15 Sporter, it is made for semi-automatic use only, its magazine has a removable spacer which limits capacity to 5 rounds, and its bolt carrier assembly has a Parco-Lubrite finish. In other respects, it is the same as the AR-15 automatic military rifle produced by Colt’s for the Army and Air Force.”

When the 1994 “assault-weapons” ban sunset in 2004, Americans already lawfully owned millions upon millions of semi-

automatic firearms of every type. With the ban gone, AR-type rifles became even more popular. Now over 21 million are owned by citizens for sport and self-defense.

Those are just a few footnotes in the history of semi-automatic designs, but it’s worth revisiting this history in greater detail, because if President Joe Biden (D), U.S. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) and other politicians who oppose the Second Amendment could get their way, they would have you think that semi-automatic rifles are new, unusual and too dangerous for citizens to own. This isn’t true, but they’d like to, once again, ban popular semi-automatic rifles before, perhaps, moving on to pistols.

To dispel their false history and politics, here is an abbreviated, but still profound history of the semi-automatic.

Firearms Technology has Been Evolving for Centuries

With the development of firearms in the mid-1320s, firearms designers concentrated on finding the most-efficient way to get their guns to actually fire. Lit embers, slow matches and linstocks were primitive and impractical in poor weather for igniting arms. The development of the flintlock in the early 17th century provided an efficient method for providing the primer with spark enough to ignite the main powder charge. Once that design gained acceptance, minds focused on how to make the advancement of arms more effective.

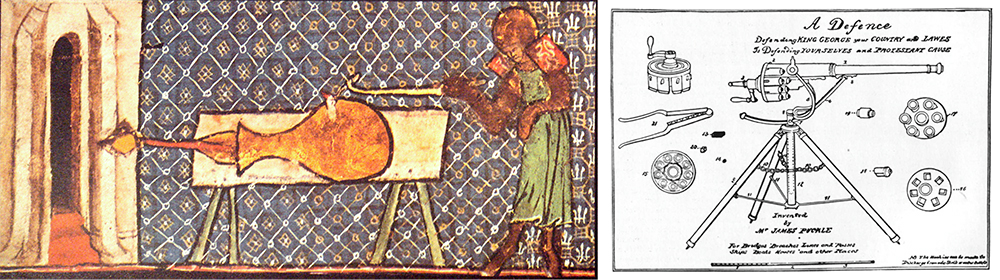

Englishman James Puckle (1667-1724) designed a repeating gun in 1718 that bore his name and that became the first gun to be called a “machine gun” in literature. The Puckle gun had a flintlock ignition system and a hand crank that rotated a number of preloaded chambers into battery so that each could be fired in turn. A revolutionary design in concept, only two Puckle guns were ever produced.

The first successful repeating rifle to see actual service in conflict was the famous air rifle designed in 1780 by Italian inventor Bartolomeo Girardoni (1744–1799) for the Austrian Army. This was a rifled carbine with an air reservoir that had a gravity-fed magazine and held twenty .46-caliber round balls. Each round was brought into battery by the flick of a thumb lever on the left side of the receiver, allowing a bullet to fall into the breech chamber. Just a cocking of the hammer primed the air chamber and a pull of the trigger released enough air pressure to propel the projectile with close to 700 feet per second velocity down range to the target, where at 100 yards it would penetrate into an inch of wood. Thought to have been used by the Austrians against Napoleon at the Battle of Wagram in 1805, it is most-famously associated as the force multiplier that Lewis & Clark used to intimidate the various Native Americans that they encountered during their Corps of Discovery between 1803-1806.

In 1818, American designer Artemus Wheeler (1781-1845) developed a revolving carbine that was field tested (without success) by the U.S. Navy. Wheeler’s carbine utilized a flintlock ignition system with a cylinder that had six .50-caliber chambers and is one of the earliest examples of the revolver as we know it today. A year following Wheeler’s revolving carbine, Boston-born Elisha Haydon Collier (1788-1856), working in England, patented a revolving handgun of similar design. There are some who postulate that a young Samuel Colt, while a merchant seaman in the far east, saw a Collier revolver, which gave him the inspiration to design his own percussion version that became the Colt Paterson revolving handgun in 1836.

The development of the percussion method of igniting firearms developed in the early 1800s, which made their use substantially more practical than the earlier flintlock method. The small percussioncap ignition system evolved into the self-contained metallic cartridge, as we know it today, by the mid-1850s.

The self-contained metallic cartridge made the development of a repeating firearm, such as the Gatling Gun (1862), a possibility. The Gatling was able to lay down a sustained rate of fire of over 600 rounds per minute, a true revolution in arms development, but it had a fatal flaw relating to its use of black powder that, when cured, would also render it obsolete.

The history of firearms is easily broken down into three distinct areas, the three P’s as we refer to them: Primer, propellant and projectile.

As we have discussed up until now, the evolution of firearms revolved around perfecting the primer or mode of igniting the main charge of propellant. The propellant, black powder, had been a constant since its invention in China around the year 800 A.D. Comprised of sulfur, charcoal and saltpeter, black powder tends to flash up instantly when ignited and is evidenced by a large cloud of white smoke. It leaves a thick residue of burnt powder called “fouling,” which, over a period of multiple shots, will constrict the diameter of the gun’s barrel, making it difficult to load further rounds of ammunition. This was not much of a concern in the age of smooth-bore muzzle-loading guns, but posed a serious problem for reloading and firing rifled arms, where the advantages of a rifle—range and accuracy—required a tight fit between the projectile and the barrel. Breechloading rifled flintlocks like the one developed by British Maj. Patrick Ferguson (1744-1780) were able to overcome this problem to a degree, but the fouling also tended to wreak havoc with most firing mechanisms after a period of time and use. With the exception of the air-rifle, black-

powder firearms tended to gum themselves up after a period of prolonged use, making innovations such as the Puckle, Wheeler, Collier and Gatling type guns unable to sustain their effectiveness under periods of extended use.

The French chemist Paul Marie Eugène Vieille (1854-1934) created Poudre B (White Powder) in 1884, and thereby changed the landscape of firearms propellants. Using a base of nitrocellulose, his new powder burned slow and hot, creating enormous chamber pressures, and left little or no fouling (residue) and very little smoke. Commonly called “smokeless-powder,” Vieille’s contribution to firearms development is still in common use today.

The advent of smokeless powder allowed firearms designers to make numerous changes to guns and how they worked. The slower- burning powder provided higher chamber pressures, increasing muzzle velocity significantly. This, in turn, led to the reduction in caliber of most small arms from .50-caliber- plus down to .30 caliber in most military arms of the period. The smaller the projectile, the further it would travel. Now rifled guns would not have to worry about fouling, so full-automatic mechanisms such as the one developed by Sir Hiram Maxim in 1884, and semi-autos, such as the ones designed by Ferdinand Ritter von Mannlicher (1848-1904), could not only sustain increased repeated firepower, but also contributed to greater range and accuracy.

Although Mannlicher’s semi-automatic rifle designs failed to initially gain acceptance due to the fact that their main design elements were based on cartridges still using black powder, other European arms developers such as Borchardt, Bergman, Luger and Mauser were quick to adapt the new powder to handgun mechanisms in the early 1890s. The most-successful semi-automatic handgun of the time would become the Mauser C96, or “broom-handle” pistol, which found a large following around the globe with over one million produced between 1896 and 1937.

Semi-Automatic Handguns

The semi-automatic handgun is now considered to be the handgun of choice for personal protection, law enforcement and most of the world’s military forces.

Although it was European designers who began the initial development of semi-automatic handguns, it was the inventive genius of American John M. Browning (1855-1926) that greatly refined and popularized them beginning with the development of the Browning/FN Model 1899/1900 in .32 ACP. Browning’s initial pocket autos were followed up by improved models in 1910 and 1922, with millions produced in numerous countries.

In the United States, the Colt .32 ACP Pocket Hammerless Model 1903, also designed by John M. Browning, swiftly became one of the most-popular carry guns in history, with over 500,000 produced between 1903 and 1945. Weighing in at only 24 ounces and only 7 inches in overall length, it was, and still is, considered to be one of the best carry guns ever made. An identical model in .380 ACP was introduced in 1908, which widened the market that Colt had for pocket pistols.

Smith & Wesson entered the semi-automatic handgun market in 1913 with the introduction of their Model 1913 in .35 S&W auto. In a case of history repeating itself, S&W designed the pistol to fire a proprietary cartridge in hopes of capturing a share of the ammunition sales as well. The Model 1913 suffered the same fate as the S&W Schofield, another gun with a proprietary cartridge that failed to find a market. Only 9,000 of both models were made before they were discontinued.

Remington, America’s oldest firearms manufacturer, followed suit in 1914 with their own semi-automatic pocket pistol in both .32 ACP and .380 ACP. Named the Model 51, it was chambered in cartridges that the public had grown to love (and still loves). The Model 51 enjoyed better sales than the Smith & Wesson semi-auto, with some 65,000 being produced before production stopped in 1926.

Gen. George S. Patton Jr. always carried a sidearm of some sort with him, as he was well known to be quite the firearms aficionado. In the spring of 1945, Patton received a Remington Model 51 in .380 ACP as a gift from Maj. Gen. Kenyon A. Joyce. Gen. Joyce thoroughly enjoyed his own Model 51, and thought that Patton would appreciate its lightness and ease of concealment. Joyce wrote to Remington asking for one to be sent to him engraved with a presentation inscription to Patton, not knowing that the firm had not produced a Model 51 since 1926. The few that they had sold once production stopped were comprised of left-over parts and those were exhausted by 1935. Appreciating the public-relations coup that would follow if Gen. Patton was photographed wearing one of its pistols, Remington located one in a Denver gun shop and rushed it to France, where it was well received by the pistol-toting general of the 3rd Army.

One of the best-loved and most-widely manufactured semi-automatics of the 20th century was the John M. Browning-designed and Colt-manufactured Model of 1911 and its subsequent variants. This seven-shot .45 ACP pistol was the standard service arm of the United States from its adoption in 1911 until it was replaced by the Beretta M9 in 1987. It is interesting to point out that the Wright Brothers were still only known for their bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio, when Browning took out his first patents on what would become the famed 1911. By the time the M9 replaced it, the entire history of manned flight had peaked with travel into space; meanwhile, the 1911 was pretty much still state-of-the-art in firepower with few changes or modifications.

European semi-automatics, many featuring design elements patented by John M. Browning, commanded the market on the continent well into the latter half of the 20th century. The Mauser Models 1910/1914/1934, as well as its HSc, competed with

the Walther PP and PPK pistols and the Beretta Model 1934 for the concealed-carry market.

Semi-Auto Shotguns

Perhaps the best-known and most- widely produced semi-automatic shotgun was the Browning Auto 5, designed in 1899. Manufactured between 1902-1998, it remains the most-produced shotgun of its type in history, having also been produced under license as the Remington Model 11, and Savage Model 720 and Model 745.

The Remington Model 1100, Beretta 3101, Benelli Super 90 and a host of other semi-auto shotguns have all proven their merits as superb hunting and sporting arms over the past century.

Semi-Auto Rifles

The German military arms designer Ferdinand von Mannlicher is credited with developing the first semi-auto rifles in 1884, but, as we stated before, their reliance on black-powder cartridges rendered them obsolete before they were actually manufactured.

It was the Mexican Gen. Manuel Mondragón (1859-1922) who developed the first practical military semi-automatic rifle in 1908. But it was not the first semi-automatic rifle on the market at the turn of the last century, as Winchester and Remington had produced their own semi-automatics for the civilian market in 1903 and 1905, respectively. The Winchester Model 1903 was a semi-auto in .22 Winchester Automatic that eventually evolved into the Model 63 in .22 LR. Both Remington and Winchester began production of their own Models of 1905 in harder- hitting .30- and .35-caliber chamberings, which proved to be quite popular in the civilian and law-enforcement markets in the years prior to World War I.

Winchester introduced a whole series of semi-autos designed by T. C. Johnson (1882-1934)—the Model 1905, 1907 and Model 1910—all hard-hitting, magazine-fed semi-automatics that not only found a civilian following but were so well-regarded they were ordered in substantial numbers by the French, British and Russian governments during World War I.

The development of what was then called self-loading rifles continued to evolve even as World War I turned Europe into a charnel house. The French Model 1917 was a gas-operated semi-automatic rifle chambered in 8 mm Lebel. About 85,000 were produced and issued to French troops who found that it was too heavy and jammed a lot.

John D. Pedersen (1881-1951), an employee of Remington Arms Company, designed America’s first military semi-automatic in 1917 with what was called the “Pedersen device.” By modifying a standard- issue Model 1903 Springfield rifle, Pedersen’s device could easily replace the bolt with a blow-back mechanism that was fed .30-18-caliber ammo from a 40-round magazine. Gen. John J. Pershing was so impressed with the possibilities of arming every soldier of the American Expeditionary Forces (A.E.F.) with a 40-round semi-automatic rifle that he ordered 500,000 of them made in hopes of employing them in the big Spring offensive of 1919. Fortunately for the soldiers of the A.E.F., the Great War ended in 1918. Contracts to produce the Pedersen device were halted after only 65,000 had been made by Remington. They were kept top secret until 1932, when they were declared obsolete and all but 100 were destroyed.

Then came the M1. “In my opinion, the M-1 Rifle is the greatest battle implement ever devised,” wrote Gen. Patton about the M1 Garand rifle in January of 1945. The M1 Garand rifle was the semi-automatic standard service arm of the U.S. military from 1936-1958. During its service run, nearly 6 million were produced, with 4 million manufactured during the 48 months we were involved in fighting the second World War. As the only military force in World War II fighting with a semi-automatic service rifle as their standard-issue arm, it is often credited with playing a major role in our eventual victory over the enemies of democracy and freedom. Jean (John) C. Garand (1888-1974) began working on the M1 in 1919 and perfected it in 1936. It remained in service until it was replaced by the similar, but selective-fire, .308-caliber M14 in 1958.

An entire library of books on the various semi-automatic rifles that soon followed have been written, but most concentrate on the military developments. The German G41 & G43 and its HK cousin; the Steyr -Aug, SKS, Beretta and FN rifles all dominated the battlefields of the late 20th century. And of course, America’s rifle, the AR-15, dominates the competition field and hunting grounds now, over 50 years since its introduction.

Sporting rifles such as the Remington Model 4 and 7400, the Ruger 10/22 and Mini 14 and the Winchester Model 63 have provided millions of Americans with endless hours of fun on the rifle range and in the hunting fields since their introduction in the post-World War II era.

Whether on the battlefield, carried in woods or marshes by hunters, their use at the National Matches and more, the semi-automatic has been a vital and efficient firearm that has been around for over a century and is the most-common firearm type owned by American citizens today.