The AR-15 is our most popular self-loading centerfire, but there are plenty of other notable rifles that came before and after.

I grew up in the Southeast at a time when just about every pickup truck had a rifle rack attached behind the seat in view for all to see. It was not unusual to see a Chevy Suburban with racks in both side windows. Winchester 94s, Marlin 336s and Savage 99s sometimes rode there, but the rifle most often seen was the Remington Model 742.

For as long as I can remember, we have had an abundance of feral hogs, and a friend at Remington once told me that more 742s were shipped to my part of the country than anywhere else. Pig shooters loved aftermarket 10-round magazines, and to this day they are available from Triple-K.

Remington introduced the first truly successful semiautomatic centerfire sporting rifle of American design in 1906. It was initially called the Autoloading Repeating Rifle and later the Model 8. It was available in a new family of rimless cartridges: .25 Rem., .30 Rem., .32 Rem. and .35 Rem. They were Remington’s answers to the .25-35 Win., .30-30 Win., .32 Special and .33 Win. cartridges.

The Model 8 is a recoil-operated autoloader designed by John Browning. Its 22-inch barrel is encircled by a large recoil spring, and both enclosed by a steel jacket. Like the A5 shotgun (also designed by Browning), during firing the barrel and breech bolt of the Model 8 travel rearward locked together for a short distance and then they separate.

As the bolt continues moving to the rear to eject a fired case, the barrel returns to its forward position. The bolt then moves forward, strips a cartridge from the magazine, shoves it into the chamber and locks into battery.

A large safety lever at the right side of the receiver blocks trigger movement and prevents the bolt from moving out of battery. The safety is easy to operate with a gloved hand, which made the Model 8 popular among those who hunted in snow country.

Unfailing reliability when subjected to extreme conditions was also a factor. The Remington rifle was not always used for sporting purposes. Two of the six lawmen who ambushed hoodlums Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow on a Louisiana country road on May 23, 1934, were armed with Model 8 rifles.

When the stock and fore-end of the Model 8 were improved in 1935, it was renamed the Model 81 Woodsmaster. The .25 Rem. was dropped and the .300 Savage added. But the handwriting was on the wall. Machined parts made the Model 81 extremely costly to manufacture, and that, along with the fact that it could not handle the .30-06 and other popular cartridges, prompted Remington to cease production in 1950 and begin designing its replacement.

Through the years I have taken deer and wild pigs with my Model 81 in .300 Savage, and to this day I had just as soon carry it in the woods as any other rifle I have owned

Billed as a new Power-Matic action capable of softening recoil, the Model 740 was Remington’s first gas-operated autoloader, and it was introduced in 1955. The .244 Rem., .308 Win., .30-06 and .280 Rem. were its initial chamberings. The Model 740 was upgraded in 1960 and renamed Model 742 Woodsmaster.

Other variations of the same design, such as the Model 7400 and Model 750, appeared through the years, and by 1981 close to 1.5 million had been sold. The number had surely exceeded two million when production ceased in 2015.

In my younger days, I often hunted black bears in the Great Smoky Mountains with a group of farmers and their hounds. The Model 742 carbine with 18.5-inch barrel in .30-06 I now have was used by one of them to take several bruins. When fed its favorite loads, it consistently shoots three bullets inside 1.5 inches at 100 yards.

The Standard Arms Company Model G patented in 1906 by Morris Smith of Wilmington, Delaware, is a most unusual gas-operated sporting rifle. It was produced in the same calibers as the Remington Model 8 and is loaded by pushing a button just forward of its trigger guard, opening the floorplate of an internal magazine and dropping in five cartridges. My rifle is in .25 Rem.

A port near the muzzle of the barrel of the Model G channels propellant gas through a valve and into a cylinder beneath the barrel. A steel rod attached to a piston inside the cylinder is connected to dual action bars that in turn are connected to the breech bolt. Turning a small valve to its Off position prevents gas from entering the cylinder, allowing the rifle to be manually operated as a slide action.

Why did Smith choose to give his rifle the capability of both semiautomatic and manual operation? While the rifle was in its design stages, smokeless propellants were fairly new and yet to be perfected, and that made some factory ammunition quite sensitive to wide swings in ambient temperature. Pressure generated on an extremely cold day in the woods may have been too low to reliably operate the Model G.

My rifle functions perfectly with hanloads loaded to maximum chamber pressure, but a reduction in velocity of 100 fps or so causes it to malfunction. Even with today’s powders, fouling builds up quickly in the gas cylinder, and that also eventually leads to malfunctions.

The rifle was available in a slide-action-only version called the Model M. Nowadays, both models are seldom seen, but if you spot a rifle with ornate brass castings serving as its buttplate, a rear sight elevator and a sliding fore-end, it will be the ill-fated Standard Arms rifle.

Winchester’s first centerfire autoloader was the Model 1905 introduced during that year. Blowback operated, a weight housed in the fore-end and connected to the bolt keeps it from opening until the bullet exits the barrel and pressure drops. Its chambering, the .35 Win. Self-Loading (WSL), pushes a 180-grain bullet along at 1,450 fps. That closely duplicates today’s .357 Mag. ammo loaded with a bullet of the same weight and fired in a Marlin 1894 lever action.

The Model 1907 introduced two years later is the same design but is chambered for the longer .351 WSL loaded with a 180-grain bullet at 1,850 fps. It was fairly popular among deer hunters, but more were used by prison guards and lawmen.

Then came a larger version of the same design called the Model 1910. Its cartridge, the .401 WSL, was loaded with 200- and 250-grain bullets at respective velocities of 2,140 fps and 1,880 fps, and that made it much more effective on game than its two smaller cousins.

Like the other two models, it was blowback operated, and since its cartridge required a heavier breech bolt counterweight, it was heftier than its main competition, the Remington Model 8. Respective production numbers for the Models 1905, 1907 and 1910 were approximately 29,000, 58,500 and 29,000, so by today’s standards not many were made.

Feeling the heat from Remington Model 742 sales during the 1950s, Winchester introduced the gas-urged Model 100 autoloader in 1960. It inherited the one-piece stock of the Model 88 lever-action introduced five years earlier and was available in .243 Win., .284 Win. and .308 Win. A carbine version with a 19-inch barrel was eventually offered.

Compared to the Model 742, the Model 100 was a slow seller with just under 263,000 built before it was discontinued in 1973. About 20 years after production of the Model 100 ceased, I spotted one in .308 Win. at a gun show. In terrible condition, it looked so sad I simply could not resist the near give-away price.

At the time I had a good friend at Winchester, and I sent it to him for a refurbishing. The barrel was in bad shape, so I asked about having it replaced with a barrel in .284 Win. Long story short, my rifle got a new stock a new barrel, a new bolt a refinished receiver and several other new parts. Fewer Model 100s were made in .284 Win. than in .243 and .308, so I hung onto mine until another friend talked me out of it.

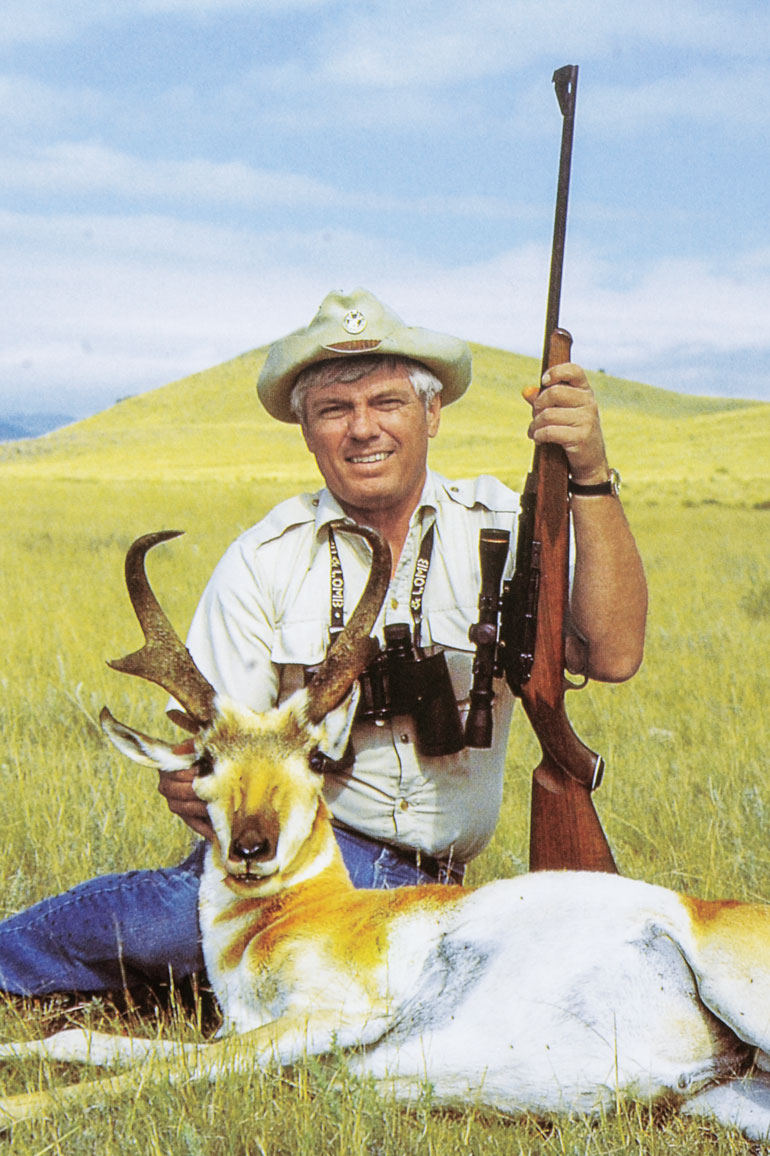

Texas is seldom thought of as a place to go for pronghorns or to use an autoloading rifle while hunting them, but quite a few years ago I took a nice buck in the Panhandle area with an HK770 in .308 Win. It was made in Germany by Heckler & Koch and introduced to the American market around 1978. It weighed the same as a Model 742 and sold for about $125 more.

Of delayed-blowback operation, the breech bolt of the HK770 is locked into battery by rollers, and its 19-inch barrel has polygonal rifling. Narrow flutes in the wall of its chamber aid in the extraction of fired cases. The rifle I used on the Texas hunt wasn’t exactly pretty, but looks proved to be only skin deep as it averaged close to an inch at 100 yards with Federal ammo.

Benelli introduced the R1 rifle during a 1992 hunt for driven game I attended in the Transylvanian mountains of central Romania. Like other firearms designed by the Italians, the R1 appears to be racing full speed ahead even when it is sitting still. It utilizes the same Auto Regulating Gas Operation system as the M4 12-gauge shotgun adopted by the U.S. Marines and by the MR1 military-style rifle in .223 Rem.

The rifle I used in Romania and one I later used on a Texas deer hunt were in .308 Win. Due to the weight and ComforTech stock, recoil was a tad less than that of a Remington 742 in .308, but they were not as accurate. The R1 was—and is—also available in .30-06, .300 Win. Mag. and .338 Win. Mag.

As I have mentioned, my father took most of his deer with a Winchester 92 in .44-40. That changed soon after Bill Ruger introduced his gas-powered .44 Mag. carbine in 1961.

Among the first produced, Dad’s Ruger had “Deerstalker” marked on its receiver. That name was quickly changed to Ruger Carbine when lawyers representing Ithaca complained about it being too close to that company’s trademarked “Deerslayer” shotgun. The little Ruger has an 18.5-inch barrel, holds four cartridges and weighs a bit less than six pounds.

In our casual shooting matches, Dad never shot a group at 50 yards as small as I could shoot with my Smith & Wesson Model 29 revolver. He was actually the better shot, but my revolver was more accurate than his carbine. But that was okay because he considered a deer standing much farther away than 100 long paces to be too far to shoot at.

The Ruger Carbine was dropped from production in 1984 and resurrected as the Deerfield Carbine in 2000. It was dropped again in 2006. In lieu of the tubular magazine of the earlier model, the Deerfield uses the same rotary magazine as today’s Ruger 77/44 carbine. If you see the original carbine, buy it and never let it get away. If its receiver has the Deerstalker marking, you are really in luck.

I saw my first Ruger Mini-14 while hunting in Rhodesia in July of 1978. That country was in the midst of a war, so professional hunter (and currently painter and sculptor of African wildlife) John Tolmay carried a Mini-14 with two taped-together 30-round magazines while we were in the bush. One of the trackers carried his .458.

The Mini-14 in .223 Rem. is still being produced by Ruger—as is its Mini-30 mate in 7.62×39 Russian, which came later. The newest addition to the family is the .300 BLK. Neither has won many shooting matches through the years, but they are great fun to shoot.

There was a time when Ye Old Hunter and other mail-order firms specializing in military surplus firearms sold M1 Garands at low prices. I bought one with my paper-route money. No FFL was required and no questions were asked—just send money and receive a gun by railway express.

That company also sold M1 Carbines, but I bought mine for $18 from the Director of Civilian Marksmanship. It did not take long for a fairly small supply of military surplus M1 Carbines to dry up, and various companies began filling the gap with civilian versions.

Most were in .30 Carbine, but in 1963 an inventor by the name of Melvin Johnson offered one in 5.7mm Spitfire—which is the .30 Carbine case necked down for .224-inch bullets. Advertised muzzle velocity for a 40-grain bullet is 3,000 fps.

Pistol-caliber carbines have become quite popular these days, but the idea is not exactly new. Back in 1985 Marlin introduced the blowback-operated Camp Carbine in 9mm Luger and .45 ACP. It had a wooden stock and a 16.5-inch barrel and was capable of slinging hot lead with the best of them.

The Browning High-Power, later to be renamed the Browning BAR and not to be confused with the military rifle bearing the same name, was introduced in 1967. Its price of $165 was about $5 less than the Remington 742. Whereas the 742 was never available in anything but standard calibers, the BAR was eventually offered in 7mm Rem. Mag., .300 Win. Mag. and .338 Win. Mag.—in addition to non-magnums like .243 and .270 Win.

It went on to outlast its competition and is still available in several variations, including walnut and synthetic stocks. The Mark III DBM (detachable box magazine) was obviously introduced to steal a bit of the AR-15 market.

There were several others, and one that springs to mind is the Harrington & Richardson Model 360 Ultra Automatic in .243 and .308 Win. I’ve never shot one of those, but a friend uses his to keep the feral pig population on his farm in check.