When the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, much of the weaponry desperately required was in short supply, most specifically some of the more advanced items. This included Browning’s groundbreaking Model 1911 pistol.

So, to fill the gap, the government contracted with Colt and Smith & Wesson to supply roughly 300,00 large-frame double-action revolvers with a cylinder shortened for the 1911’s .45 ACP service cartridge. Both featured a 5.5″ barrel.

Hartford vs. Springfield

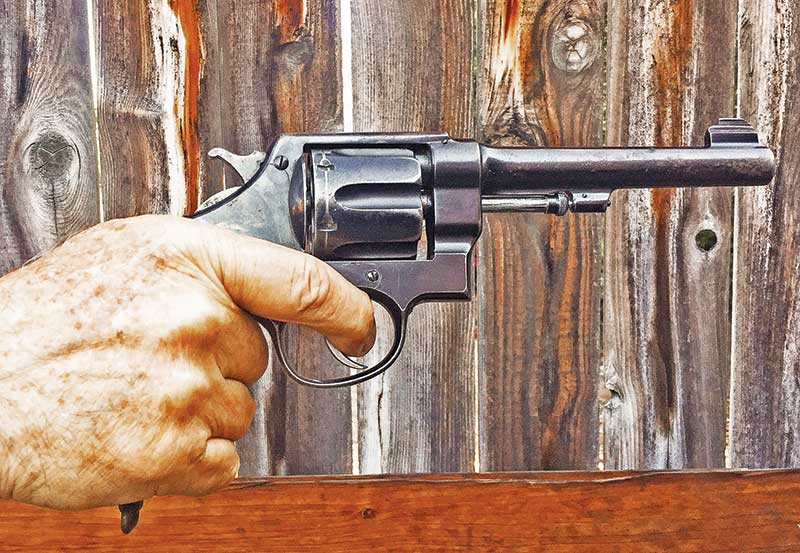

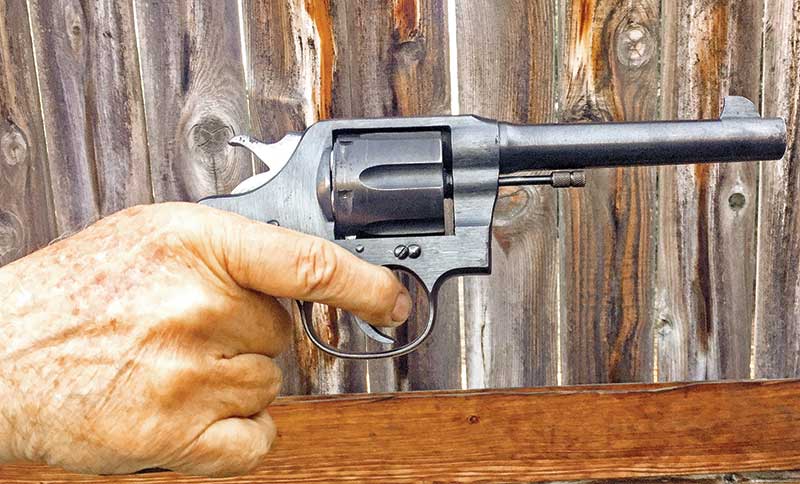

Colt’s contribution was essentially a Model 1909 New Service with a weight of 2.5 lbs. Smith & Wesson’s entry was essentially a 2nd Model Hand Ejector weighing 4 oz. less than the Colt.

For this story we managed to luck into one of each, courtesy of our shooting buddies Nils Grevillius (S&W) and John Wightman (Colt). Both specimens have had — through the years — more than one owner since production ceased in 1920. And, not surprisingly, there had been some minor alterations to the original guns.

The Smith’s original front sight had been replaced and our Colt had seen its original issue wooden stocks replaced by black hard rubber panels. Other than this, both guns were dead stock, right down to the “Property of United States Government” stamp on the underside of the barrel.

The triggers on both guns were in keeping with the usual Colt/Smith results from the era. The single-action pull on the Colt was a fairly manageable 4-¾ lbs., while the double-action pull stacked horrendously to the break point at a little over 17 lbs.

The Smith’s single-action pull broke at 2 ¾ lbs. while the double-action pull was an infinitely smoother — in comparison to the “stagier” Colt — 12 lbs. So, in terms of trigger manageability in either mode, the Smith was the clear winner. But in all fairness, neither gun as issued would pass muster for a modern DA revolver competition.

Vive La Difference!

Our smaller handed shooters preferred the Smith. Cosmetically, the Smith had a nicer finish. Although not critical on a military arm, it did give the S&W a leg up in terms of civilian appeal after the horrors of the Western Front became just a bad memory.

Other Smith vs. Colt signature operational features were what you’d expect from guns of the era: Left to right cylinder rotation on the Colt, a naked ejector rod and a pull-to-open cylinder latch. For the Smith, of course, you have right-to-left cylinder rotation, semi-shrouded ejector rod and a push-to-open cylinder latch.

Both guns featured the obligatory threaded lanyard ring on the butt. For a military handgun, lanyards were most definitely not a mere affectation, particularly if you were on horseback.

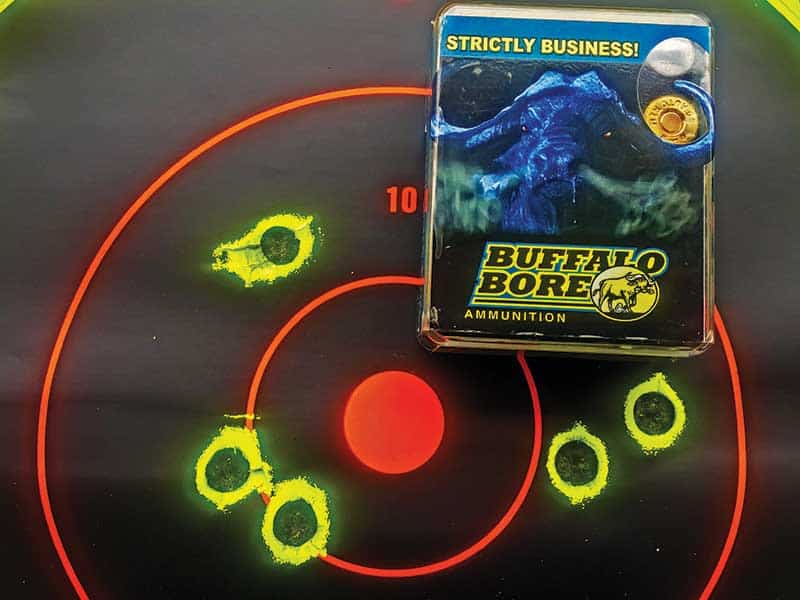

Of course, we shot ’em both using some vintage GI issue .45 ACP 230-grain hardball, along with some Magtech 180-grain JHPs and — once we got tired of moon-clipping — some Buffalo Bore .45 Auto Rim stuff.

Shoot ’em If You Got ’em

The small sights on both guns made shooting good groups at 25 yards something of a challenge, but the top performers were the Magtech 180-grain JHPs from the Colt and Buffalo Bore’s 225-grain .45 Auto Rim wadcutters from the Smith.

It’s worth noting everything we shot seemed to generate more felt recoil than we’ve ever noticed from a 1911 auto. This appeared to be as much a function of the narrower backstrap and grip angle of the M1917 revolvers as much as anything.

Okay, from a combat-desirability aspect — not to mention carryability — both the Smith & Colt 1917s were “round guns,” bulkier and heavier than the 39-oz. Model 1911 auto, a classic “flat gun.” But they were critical additions to the sidearm shortage of WWI and I am gonna guess any soldier in desperate need of a handgun would most likely have been grateful as heck for a 1917.

Of course, revolvers still played a role in WWII — most specifically the Smith .38 Victory Model and the Colt Commando, while Smith’s J-Frame lightweight aluminum-framed Aircrewman put in a limited appearance in the early days of the Cold War.

Truth be told, handguns — aside from serving as badges of rank — were fairly low on the list of essential weaponry. But as Jeff Cooper once said: “Handguns don’t win wars, but they do save the lives of men who fight them.”