The American Doughboy, immortalized in photo, film and statuary, is almost exclusively depicted wielding either the classic M1903 Springfield or the quickly adopted and fielded M1917 bolt-action rifles. While other iconic weapons of the era certainly loom large in the American consciousness, such as the M1911 pistol and M1897 shotgun, the two rifles have a special place in the hearts of historians, collectors and sportsmen the world over.

This is perhaps because World War I was arguably the last rifleman’s war, during which the rifle’s place as the most lethal arm on the battlefield was completely eclipsed by artillery, machine guns and all manner of other technological contraptions.

While the M1903’s total production numbers reached 914,625 by Nov. 30, 1918, the 587,468 M1903 rifles on hand when hostilities started (as tallied by the Ordnance Department after the war) were woefully inadequate to supply the vast number of men that would eventually be drawn into service during the war. Famously, this caused Brig. Gen. William Crozier, the U.S. Army’s Chief of Ordnance, to request authority to being the “[e]mergency procurement of small arms other than of U.S. design.”

This led to the adoption of a slightly modified British P14 Enfield rifle, re-chambered for the U.S. standard Model 1906 cartridge (.30-’06 Sprg.) and designated the Model of 1917.

Four largely forgotten infantry rifles that were used in some capacity by the U.S. during World War I. From top to bottom: Springfield Trapdoor, Krag-Jorgenson, Ross Mk II*** and an American-made M1891 Mosin-Nagant rifle.

Four largely forgotten infantry rifles that were used in some capacity by the U.S. during World War I. From top to bottom: Springfield Trapdoor, Krag-Jorgenson, Ross Mk II*** and an American-made M1891 Mosin-Nagant rifle.

But this was not a painless or fast process, and between military and bureaucratic tangles along with serious parts interchangeability issues, the first production rifles didn’t start rolling off the line until September – approximately five months after both the decision was made to adopt it and the official US entry into the war.

While the fielding of the M1917 is rightly regarded as an impressive industrial feat by the three commercial factories tasked with its production (indeed more M1917s saw field service than M1903s), the fact remained that in the meantime more rifles were still desperately needed to train recruits, guard stateside infrastructure and even deploy overseas.

“Very serviceable weapons, although not of the present standard model for the United States Army”

The first and most obvious choice to supplement the shortfall of “modern” rifles was the Krag-Jorgenson pattern of rifles, produced between 1894 and 1903 by Springfield Armory. While not quite as excellent as the M1903 that replaced them (the Krag lacks a charger loading system, utilizes a ballistically inferior cartridge and is overall longer), they were still very suitable weapons for use by an early 20th century military, as they fit the mold of small-bore and smokeless powder that had become the practical requirement.

After the adoption of the M1903s, Krag rifles remained the primary arm of many state military units as the M1903s slowly trickled out to the entire force. In addition, many were disbursed to various organizations that had a need for a recently obsolete military rifle for marksmanship training, drill practice or ceremonial use. A majority, however, were simply recalled to and stored in government arsenals awaiting either future use or disposition.

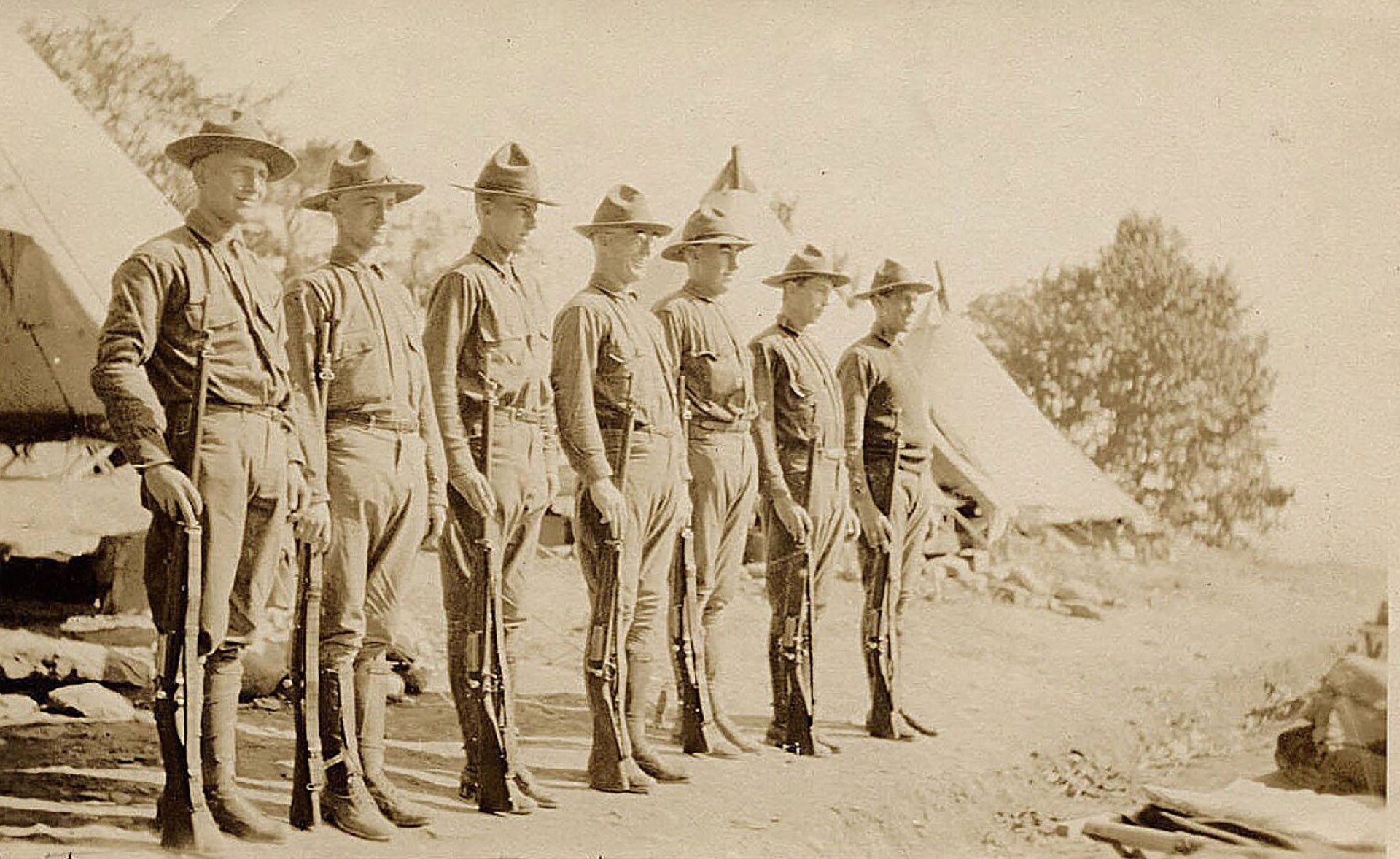

Men of the New York Guard standing at attention with their Krag-Jorgenson rifles.

Men of the New York Guard standing at attention with their Krag-Jorgenson rifles.

In a May 17, 1917, memorandum from the Office of the Chief of Ordnance, they report that, “there are in in the possession of Educational Institutions 44,708 Krags and in the possession of Rifle Clubs 7,421.” Because the shortage of rifles was apparent early on, Brig. Gen. Crozier stated that even though “it is not necessary that troops shall go into campaign armed with the [Krag] rifle, it is possible that some of these rifles may be required for drill and target practice,” and he recommended that the issue of Krag rifles to groups “other than federal forces be suspended.” Almost certainly acting under this advisement, the Secretary of War cut off rifle clubs, schools and colleges in an order dated May 9, 1917.

One would think that the rifles held by the federal government would be the easiest to put into immediate service, since they just needed to be brought out of storage – yet they weren’t always in “fighting ready” condition. In the same May 17 memorandum, the Ordnance Department reported that, “There are on hand approximately 210,000 Krag rifles and carbines, of which 102,000 are serviceable,” and that, “The unserviceable guns and ammunition require overhauling and putting in shape.”

A comparison between the four rifles’ actions.

A comparison between the four rifles’ actions.

A rapid series of messages back and forth between the Ordnance Office, and the commanders of both Springfield Armory and Watervliet Arsenal details some of this process. In the correspondence, the three parties work out the particulars of sending some 88,952 unserviceable Krag rifles and carbines, along with Springfield’s supply of spare parts, to Watervliet for overhaul. This included not only the M1898 rifles, but also approximately 2,500 M1892 and M1896 rifles as well as “bayonets and appendages.”

As discussed above, and as envisioned by Ordnance officials at the time, the Krag saw heavy use training the ever-growing body of American fighting men as they prepared to deploy to Europe. The broader population had become aware of the rifle shortage, however, and many wrote to their elected officials to express their concern that their sons might be forced to drill with broomsticks or wooden rifles.

The Krag was often used to allay these fears, with Brig. Gen. Crozier pointing out to one worried mother that, “There have been for some time at each cantonment of the National Army 55,000 Krag Jorgenson rifles for training; these were soon after their supply followed by an additional 2,000 of these rifles, which are very serviceable weapons, although not of the present standard model for the United States Army.”

Krag rifles being carried by men of the American Expeditionary Force during World War I.

Krag rifles being carried by men of the American Expeditionary Force during World War I.

Some Krags did see limited service overseas during the war, with at least the 14th United States Engineers carrying them all the way into France. By July 1918 however, they had been switched out for M1903 rifles and the II Corps Ordnance Officer reported disbursing 1,157 M1903s in exchange for at least 972 Krag rifles. The stated reason for the switch was to ensure ammunition standardization in whatever area the unit was assigned to.

“When will they be put on Flintlocks”?

Even older US military rifles were brought back into service to help alleviate the acute shortage of functional weaponry. On Aug. 23, 1917, an officer from the Small Arms Division of the Ordnance Department instructed the commanding officer of the Rock Island Arsenal to “put into good condition” the 2,927 unserviceable Trapdoor Springfield rifles on hand at the arsenal. This action, along with the work on Krag rifles and carbines, earned the scorn of some of the workers – as reflected in one anonymous complaint written to U.S. Senator G.M. Hitchcock and forwarded to the Chief of Ordnance:

Dear Sir:

Of my own personal knowledge I know that there is a force of men at work at R. I. A. on worn-out Krag-Jorgenson rifles used in the Philippine campaign of ’99 and 1900 – also another force on caliber .45 Springfields discarded at that time.

It’s a standing joke among these employees as to when they will be put on Flintlocks.

Now I don’t know if this will put me in jail, but I think it should be asked of Mr. Baker [the Secretary of War] if this can in any way assist in arming our men to defeat the Huns.

Despite this anonymous worker’s skepticism about the usefulness of Trapdoors to the war effort, they were actually in high demand by a number of states which wanted rifles for stateside security use. New York in particular, while angling to acquire more modern arms from Canadian sources, articulated a need to guard “lines of transportation and communication over which are sent Federal Supplies” and that the “Prospect of [a] shipping strike on water front N.Y. makes [the shortage of rifles] serious.” Brig. Gen. Crozier, somewhat tersely, reminded the writer that “the governor of the State of New York was authorized to requisition guns from educational institutions and rifles clubs of New York,” and that he had not drawn all that he was able.

The muzzles of the four rifles compared. From left to right: Springfield Trapdoor, Krag-Jorgenson, Ross Mk II*** and an American-made M1891 Mosin-Nagant rifle.

The muzzles of the four rifles compared. From left to right: Springfield Trapdoor, Krag-Jorgenson, Ross Mk II*** and an American-made M1891 Mosin-Nagant rifle.

Additionally, he stated that the governor was issued 500 Trapdoor Springfields on Aug. 11, 1917, and that, “There are on hand, not already allotted to state organizations, 7,979 rifles of caliber .45. The demand is very heavy for this character of equipment for use of home guard organizations; about 30 states have not as yet been supplied, and no more rifles can properly be issued to this state. The former Adjutant General was fully advised as to this.”

So even though the Trapdoor was thoroughly out of modern military fashion by 1917, being not only a single-shot breechloader, but also blackpowder and large bore; thousands of them still played a role in the process of getting American fighting men and their equipment safely across the country and loaded onto ships bound for France.

“War Department has no objection to State of New York purchasing rifles from Dominion Government”

While Trapdoors were useful in certain roles, there still existed a stateside need for “modern” rifles more akin to the M1903 and M1917 rifles that were to be used against the Hun (and the RIA workers were, after all, not going to be tasked with refurbishing flintlocks). As mentioned above, New York was especially interested in obtaining additional rifles, particularly since its harbors were a key point of embarkation. Fortunately, America’s neighbor to the north had a number of older pattern Ross Rifles that they were willing to sell across the border to help Uncle Sam.

A closer look at the features of the action on the Ross Mk II*** rifle.

A closer look at the features of the action on the Ross Mk II*** rifle.

These took the form of Ross Mk II*** rifles, also known as the Model 1905. Featuring a straight-pull action, the Ross fires the .303 British cartridge from an internal magazine.

While the later Ross Rifles were charger fed, the Mk II*** featured a follower depressing lever on the side of the rifle that allows the user to “dump” the cartridges into the rifle, instead of inserting them singly. Even though the Mk II*** was already obsolete by Canadian standards, Ross Rifles as a species also ran into problems in the harsh fighting conditions of the trenches.

This, combined with tight tolerances better suited for a target rifle and loose British ammunition tolerances, resulted in a majority of Ross Rifles being withdrawn from frontline service in Europe and replaced by the Short, Magazine Lee-Enfield.

Despite these issues, the rifles were certainly suitable for stateside use, and more importantly, were actually available for transfer south in September 1917. New York was so eager to get their hands on these rifles that they actually started negotiations directly with Canada and secured the ability to purchase 15,000 Ross Rifles and ammunition for them, with the purchase price recorded as being $12.50 for the rifle, bayonet and scabbard. Their plans hit a snag however, as the rifles would be subject to an import duty of 35 percent, making a relatively good deal suddenly less appealing.

Men of the New York Guard armed with Ross Rifles.

Men of the New York Guard armed with Ross Rifles.

New York requested either an exemption to the tax, or reimbursement for the fee through the federal government. Instead, Brig. Gen. Crozier informed the Adjutant General for New York that he was already in talks with the Canadians for rifles, and that he would be able to sell some quantity of the procured rifles to the state. In the end, the ordnance department was able to procure some 20,000 Ross Rifles for use, with 10,000 of them going to New York and the difference being used for training troops in federal service.

The rifles acquired under this contract are identified by a “U.S.” stamping on the underside of the wrist, and “flaming bomb” stamps in the wood both fore and aft of the trigger guard and magazine assembly. Additionally, a new inventory or serial number was also added to the underside of the wrist. This broke from the Canadian practice of marking model, serial number, and unit assignment on the right side of the buttstock, and many of the rifles feature multiple struck through markings denoting the rifle changing hands.

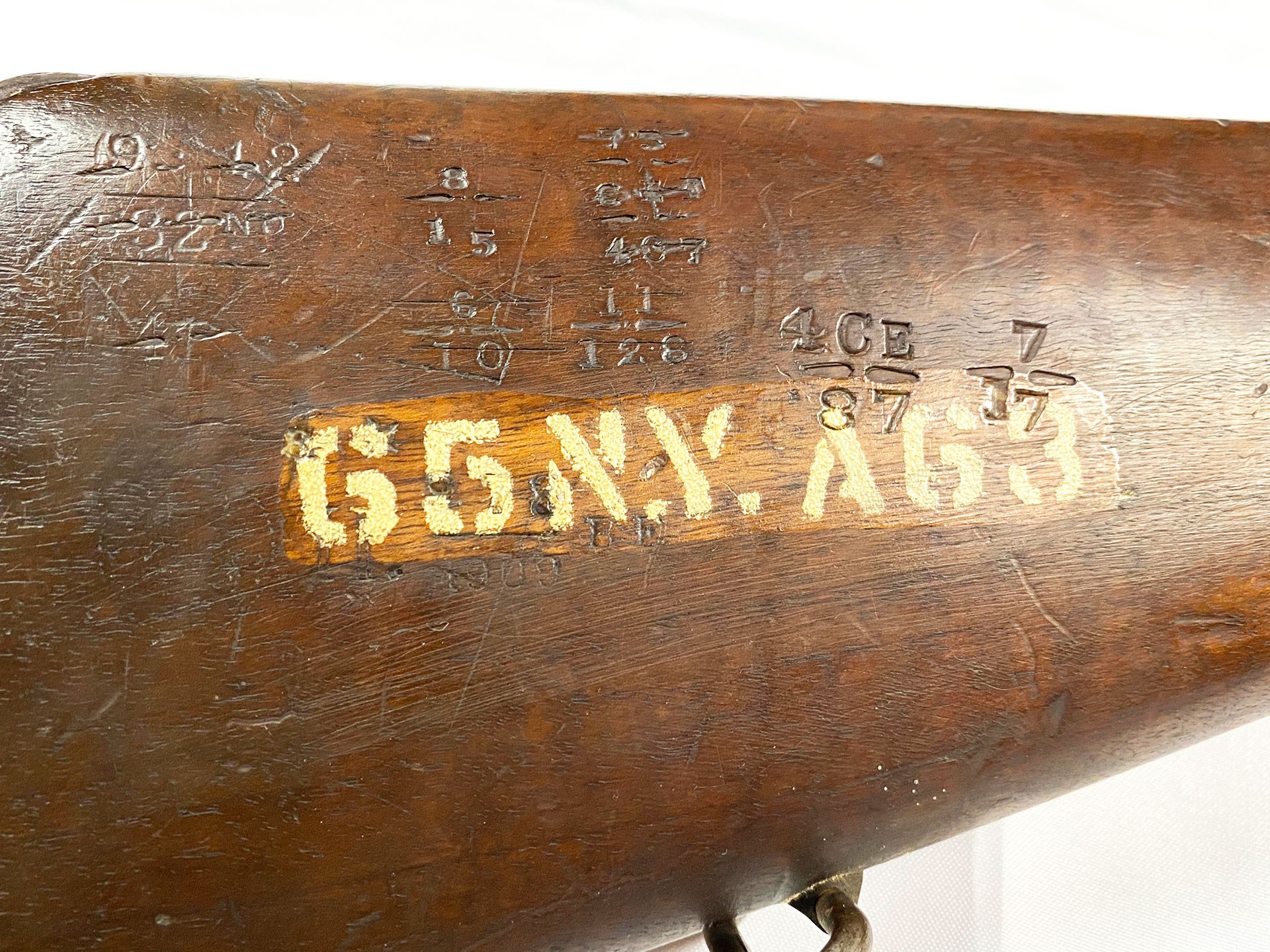

New York Guard markings painted over older Canadian service stamps on a Ross Mk II*** rifle.

New York Guard markings painted over older Canadian service stamps on a Ross Mk II*** rifle.

The rifles that made it to New York primarily found themselves in the hands of the New York Guard (not to be confused with the New York National Guard). Since the New York Guard was a purely state organization, it was not subject to being called into federal service and was used by the state for protecting infrastructure and other critical internal security roles. As the pictured rifle and period unit photograph shows, rifles distributed to the NYG often received painted on unit markings done right over top of the original Canadian stampings.

“The rifle will be known as the Russian 3 Line Rifle”

While the government looked across its northern border for the Ross rifle, they didn’t have to look nearly as far for another foreign service rifle to supplement their supply of rifles. That is because two U.S. firearm makers – the New Remington Rifle Company in Bridgeport, Conn., and New England Westinghouse in East Springfield, Mass. – had been hard at work producing Model 1891 Mosin-Nagant rifles. Both of the companies were subsidiary organizations to their more famous parent companies, and had been designed almost exclusively to handle the massive Russian contracts.

On June 6, 1917, the vice president of Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company wrote to the Ordnance Department with a proposal. The company had “been successful in adapting the Russian type of military rifle to the use of U.S. ammunition, with very slight changes.” All of the existing forgings could be used, with the goal to “develop a military rifle of about the same length as the Springfield rifle and one which [the company] experts feel could in an emergency be usefully employed by our own troops.”

Ten days later, a polite but lukewarm response was composed by a major from the Small Arms Division, stating that “it is not deemed advisable to have a third model of rifle in the service, at the present time,” although he did suggest that the rifle could be sent to Springfield Armory for further evaluation.

A left-side view of a New England Westinghouse manufactured Model 1891 Mosin-Nagant rifle, which was commonly referred to as the “Russian rifle.”

A left-side view of a New England Westinghouse manufactured Model 1891 Mosin-Nagant rifle, which was commonly referred to as the “Russian rifle.”

In the closing days of 1917, however, the War Department circled back to the idea of using the Russian rifles – albeit in their original caliber of 7.62×54 mm R. The new Soviet government had entered into an armistice with the Central Powers on Dec. 15, 1917, and began formal peace negotiations on December 22 at Brest-Litovsk in Ukraine. It was likely at this point that American War Department and Ordnance officials felt safe in assuming that the new Russian government’s demand (and willingness to pay) for the rifles would be greatly reduced as they exited the war and turned their attentions inward.

The loss of this contract would economically harm the companies of course, as they had been created almost exclusively to handle the Russian contracts. The U.S. decision to order Russian rifles has sometimes been framed solely as a “too big to fail” bail out of sorts, designed to prop up floundering US companies. However, primary source documents from the era reveal a bit more nuance and show that there were serious war material production concerns at stake as well.

The New England Westinghouse Contract is particularly interesting, because the ultimate plan was to convert the factory over for the production of 15,000 heavy machine guns — something indispensable on the modern battlefield.

Men of the U.S. Guards armed with Model 1891 rifles.

Men of the U.S. Guards armed with Model 1891 rifles.

In order to, “insure production it was found necessary to provide means of preserving the organization of [N.E.W.] until such a time as the manufacture of the machine guns could be started.” As one could imagine, the loss of skilled laborers, managers and inspectors would have an extremely harmful effect on the ability of the company to transition over to an entirely new set of weapons. While the companies certainly benefited from government picking up their contract for Russian rifles, the government war effort was at least an equal beneficiary.

Losing no further time, the Secretary of War placed an order with the New England Westinghouse Company of Springfield Massachusetts on Dec. 29, 1917, for “the manufacture of 200,000 Russian rifles on the basis of cost without profit to [the] company,” which equated a contract price of $15 per rifle. Hedging their bets a little bit, it was “stated that an option was given to the Russian Government until May 1, 1918, to purchase such Russian rifles as [produced by N.E.W.].” The plan was that the company would continue manufacturing the Russian rifles, and the government would pay New England Westinghouse $600,000 per-month until May 1918, at which time $3 million would be expended and the machine gun production lines were scheduled to be operational.

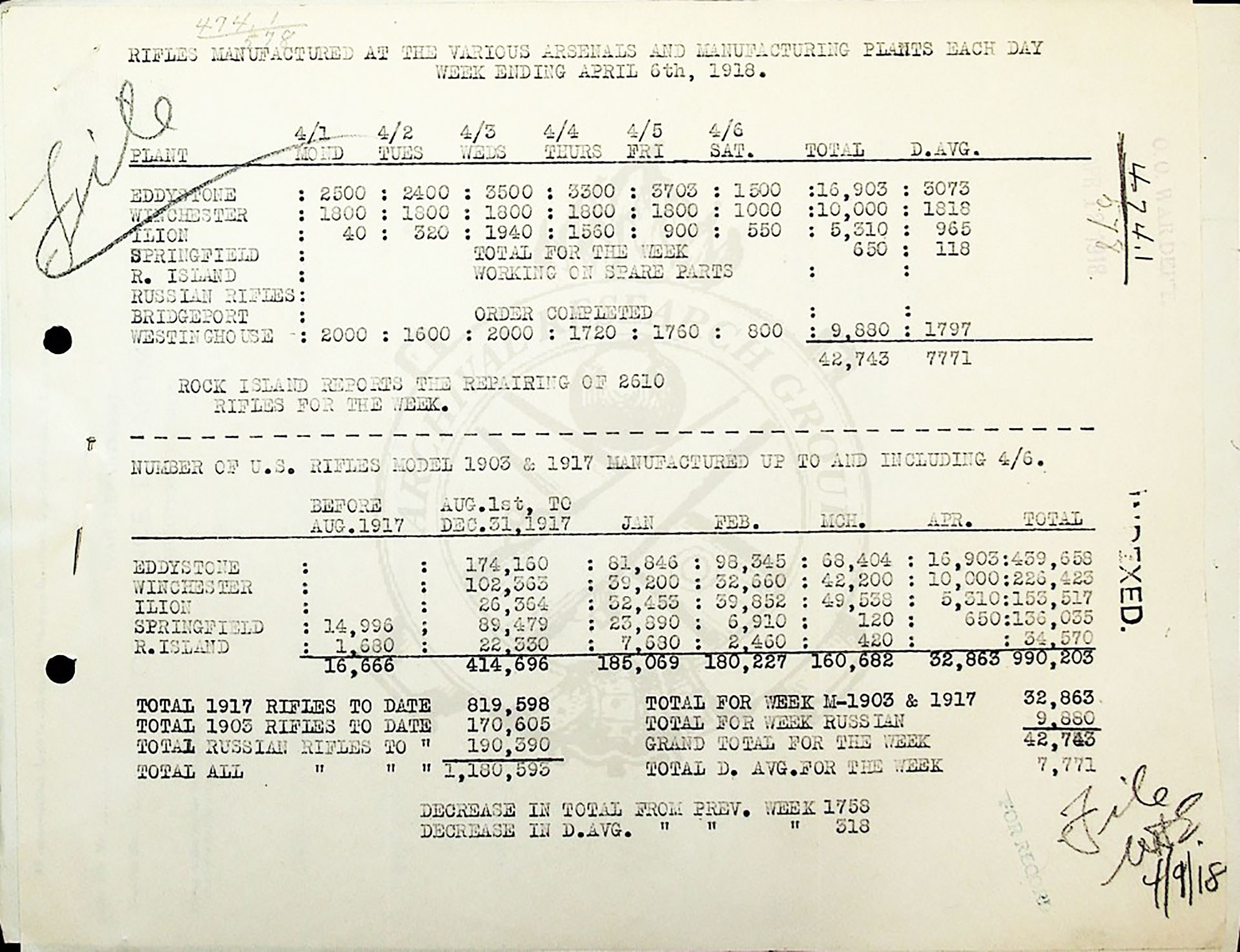

A document comparing production numbers of the M1903, M1917 and M1891 rifles from their various manufacturers. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

A document comparing production numbers of the M1903, M1917 and M1891 rifles from their various manufacturers. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

The New Remington Rifle Company of Bridgeport, Conn., wasn’t far behind, with the Acting Chief of Ordnance placing an order on Jan. 7, 1918 for 78,950 already produced rifles. The cost would be set at $30 per rifle, for a total contract price of “$2,368,500 to be paid […] upon delivery and acceptance of said rifles.” Remington did continue to make rifles for the Russian government as well, but downward adjustments to the contract by the Russians caused Remington to reduce the number of men on the job. As in the case of New England Westinghouse, the purchases made by the U.S. government appear to have been made to allow the company “to keep a substantial portion of its organization together until it can be gradually diverted from work on the Russian rifles to work on the United States Government’s orders.”

Regarding nomenclature, there seems to have been some attempt by the Ordnance Department to give the M1891 in U.S. service the name “Russian 3 Line Rifle,” although in the vast majority of official correspondence they are simply referred to as “Russian rifles.” When it comes to weapons produced primarily for U.S. service, you perhaps would think that rifles of the same type would have the same inspection process when it came time to certifying their suitability for use. This was not the case with the Russian rifles.

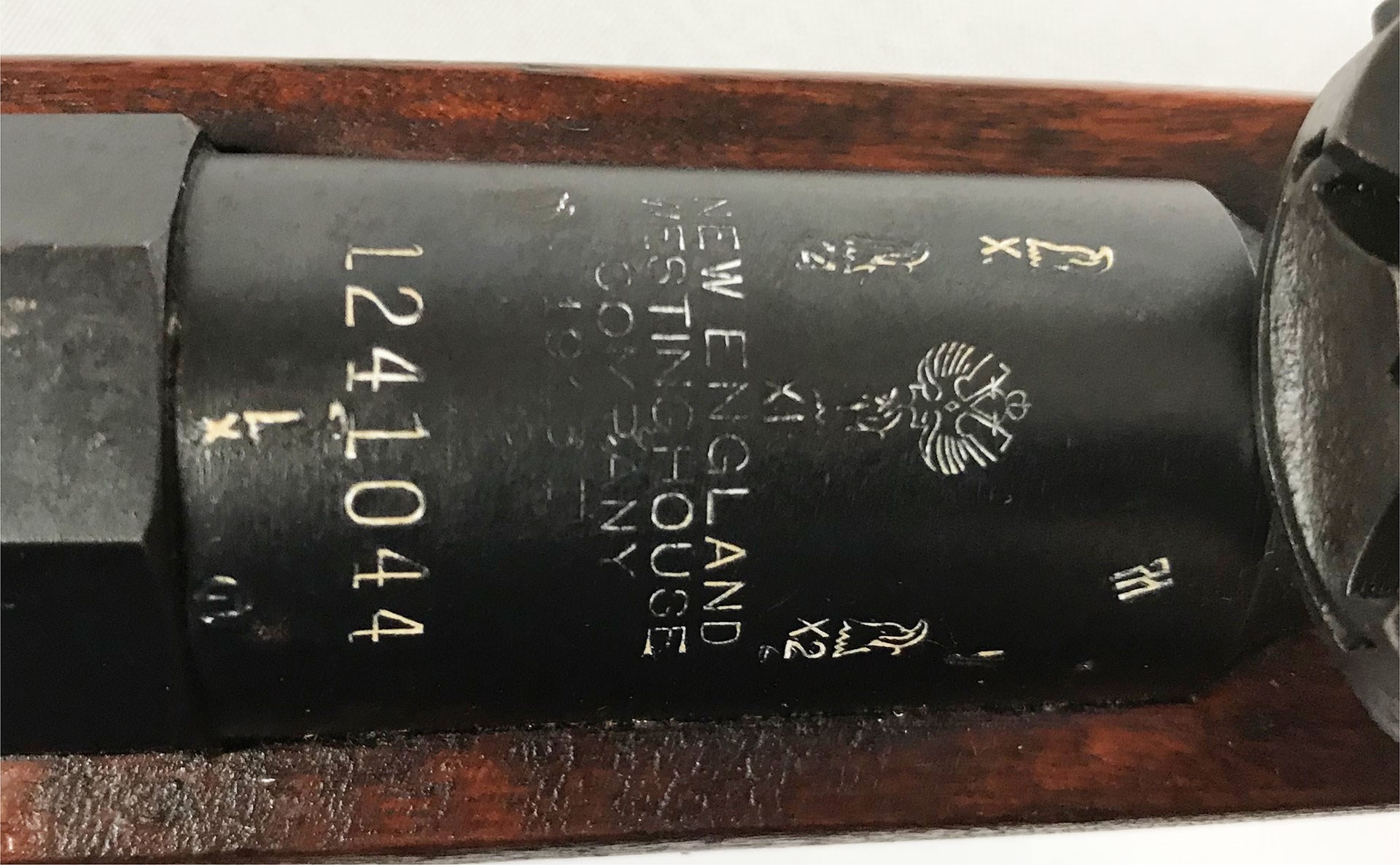

A closer look at the receiver markings of a Westinghouse manufactured M1891 rifle.

A closer look at the receiver markings of a Westinghouse manufactured M1891 rifle.

In general, Remington took a relatively minimalist approach and usually chose to simply stamp a flaming ordnance bomb and maybe an eagle head over “U.S.” on the bottom of the stock, just forward of the magazine. The inspection team at New England Westinghouse, on the other hand, must have decided to put their inspectors to work, as the rifles produced during this contract run are covered by a bevy of eagle head stampings on both the wood and the metal.

Documents drafted shortly after the war indicate that many thousands of these rifles were shipped across the United States for use as training weapons and stateside guard duty, with 12,954 being issued to the National Guard, 41,705 to various Home Guard organizations and approximately 25,000 to the U.S. Guards (a Federal military internal security organization composed of men aged between 31 and 40). On Governor’s Island in the New York Harbor for instance, the 300 men of the 9th U.S. Guards stationed at that post were armed exclusively with “266 Russian type rifles.” Post-war, Camp Logan, Texas, reported it had “532 Rifles, Russian”, along with an equal number of M1898 Krags that it wanted to divest itself of.

An eagle head inspection stamp in the wood of the Westinghouse manufactured M1891.

An eagle head inspection stamp in the wood of the Westinghouse manufactured M1891.

The largest number of Russian rifles were shipped to schools and colleges with programs of military instruction. Many of these had been forced to give up their Krags or other weapons during the early days following the U.S. entry into the war, and would likely have welcomed brand new (although non-standard) firearms into their arms rooms. Student Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C.) detachments received a staggering 109,700 rifles, while Reserve Officer Training Corps (R.O.T.C.) programs received 5,597.

That’s not to say they were always received with open arms however, and the Commanding Officer of the 5th Battalion, U.S. Guards stationed at Fort Robinson, Neb., had some critiques:

Subject: Russian Rifles

Stating a few apparent defects in the construction of Russian rifle, due perhaps to lack of knowledge of its nomenclature:

Can be safety locked only by pulling back knob of cocking piece with fingers and turning it to the left which makes it impossible to pull trigger or open chamber.

Examination has failed to reveal a cut off.

Apparently there is no provision for stacking arms.

Sailors from the U.S.S. Olympia’s shore party armed with M1891 rifles during the U.S. intervention in the Russian civil war in September 1918.

Sailors from the U.S.S. Olympia’s shore party armed with M1891 rifles during the U.S. intervention in the Russian civil war in September 1918.

Despite its inferiority to the M1903 and M1917, the Russian rifles did actually see combat service with the United States military. A large portion of the U.S. soldiers and sailors tasked with the controversial intervention in the Russian Civil War were armed with American made Mosin-Nagants, something that undoubtedly simplified logistics when it came to spare parts and ammunition. Those rifles didn’t sail home with the troops in June 1919, however, as a telegram from Brig. Gen. Wilds P. Richardson, the man tasked with organizing the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Russia, reported that the Russian rifles had been turned over to the British by the departing “Polar Bear” personnel.

All Pulling for Victory

Although not designed as a military rifle like the others, an honorable mention should also go to the 1,800 Winchester Model 1894 lever action rifles chambered in .30 W.C.F. that were put into service in the Pacific Northwest guarding the pine forests. These so called “Spruce Guns” were used by the U.S. Army Signal Corps to secure this critical national resource from possible work stoppages or sabotage.

Although the vast majority of the non-standard rifles detailed above did not see overseas service, they did free up a staggering number of M1903s and M1917s for service abroad. They further provided security for the home front, not only guarding physical places and things, but also providing peace of mind to a nation newly at war. While they may not be enshrined in small town statues or immortalized in film being held by the square-jawed doughboy, they allowed the United States to quickly mass critical resources overseas and help bring about the end of World War I.

A special thanks is owed to Archival Research Group for providing high quality scans of the primary source documents used to write this article.