When a new cartridge is introduced, its origins can often be traced to a cartridge P.O. Ackley had his hand in developing decades previously. A case in point is Hornady’s new .17 Hornet with roots back to the beginning of .17-caliber cartridges in the years following World War II.

In Handbook for Shooters and Reloaders, Volume II (1966), Ackley writes about himself: “The author may or may not have been the originator of the .17 caliber in this country. The reason the author made the first .17 caliber was the result of a deal with the late C.H. O’Neil of OKH fame. During the first years of World War II, Mr. O’Neil came up with the idea of a .17 caliber cartridge, believed to have been based on the .22 Hornet.

The author obtained the tools, which took some time, and by the time the tools were ready Mr. O’Neil had other things to occupy his mind, so that the project remained static until 1945. Having the tools, it was decided to make a few barrels. The first one was chambered for the so-called .17 Pee Wee, which was simply the .30 Carbine cartridge necked down to .17, and the first rifle was built . . . by an Oregon gunsmith and was exactly right for this small cartridge. Bullets were made out of copper wire and results on small game such as prairie dogs were quite amazing. The impossibility of getting suitable actions for the .17 Pee Wee cartridge, made it necessary to design several other cartridges which would be suitable for available actions. The first one was the .17 Hornet, closely followed by the .17 Bee and later by the .17/222.”

Ackley describes the .17 Hornet as sort of an “improved” .22 Hornet necked down to .17 caliber. Ackley’s load data lists 25-grain bullets with a velocity of 3,585 fps from 12.0 grains of 4198 and 3,570 fps from 11.5 grains of 4227.

Hornady also calls its new .17-caliber cartridge the .17 Hornet. The Hornady .17 case, however, is a bit shorter in length and to the base of the shoulder than the Ackley case. The shoulder diameter of the Hornady case is also a bit wider in diameter than the Ackley. The new case most likely is shorter so it can be loaded with relatively long and pointed Hornady 20- and 25-grain V-MAX bullets and still retain the same 1.723-inch overall cartridge length of the .22 Hornet. That length allows Hornady’s .17 Hornet to fit in existing magazines and bolt actions originally intended for the .22 Hornet, like the CZ 527, Ruger 77/22 Hornet and Savage Model 25.

Because the .17 Hornady Hornet case is smaller than the .17 Ackley Hornet case, handloading data for the two cartridges should not be casually interchanged. Hodgdon Powder is the only current source of handloading data I could find for the new and old .17s. The Hodgdon’s 2012 Annual Manual and the Hodgdon website list about the same maximum loads for the .17 Ackley Hornet and .17 Hornet with some powders. However, maximum powder charges for the .17 Ackley are 0.2 to 0.7 grain heavier than for the .17 Hornady. That is a significant difference in such a small cartridge case that only holds about 12 grains of powder.

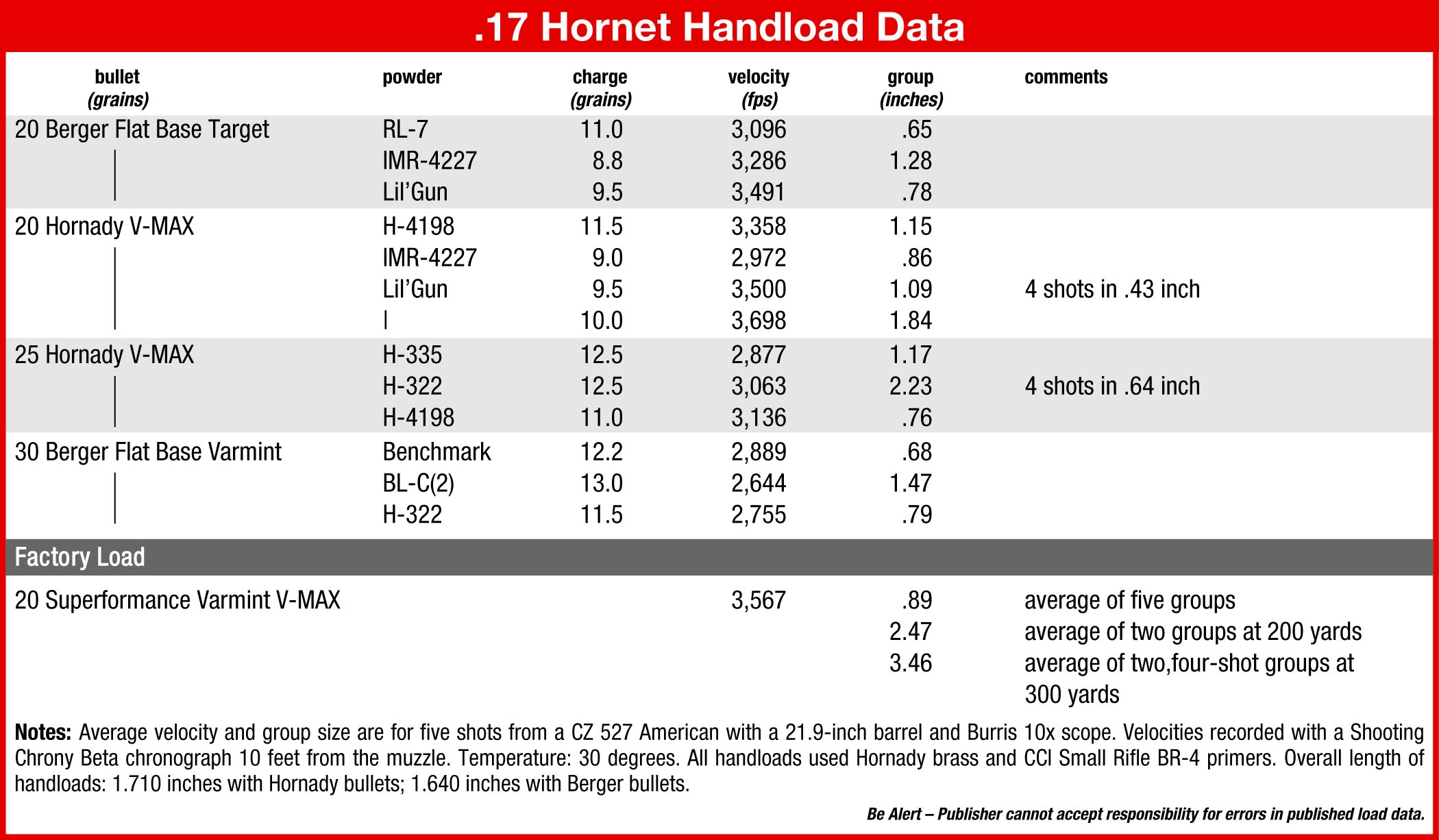

Hornady loads its .17 Hornet Superformance Varmint cartridges with 20-grain V-MAX bullets and 15.5-grain NTX bullets, with a stated muzzle velocity of 3,650 fps for the V-MAX and 3,870 fps for the NTX. The V-MAX bullets had an average velocity of 3,567 fps for 10 shots recorded 10 feet in front of the muzzle of the 21.90-inch barrel of a CZ 527 American.

CZ calls the 527 a “micro-Mauser” due to its nonrotating claw extractor that grabs the rim of a case as it’s pushed forward out of the magazine and blade ejector. The supplied scope rings that clamp on the square bridge of the receiver are a nice touch. The 527 has a single-set trigger with a pull of 3.5 pounds that contains some creep, but pushing the trigger forward “sets” it, and pull weight changes to a light one pound. The 527’s barrel is slender with a diameter of just over .5 inch at the muzzle. The rifle weighs right at 7 pounds with a Turkish walnut stock and a Burris 10x scope.

The little rifle and varmint loads made an accurate pair, too. Five, five-shot groups measured an average of .89 inch at 100 yards. Two, five-shot groups averaged 2.47 inches at 200 yards and 3.46 inches at 300 yards. Recoil was so gentle the scope’s crosshairs barely bounced, and when shooting I often saw a tiny black hole appear on the white target paper at 100 yards. After shooting the .17 Hornet, the recoil and muzzle blast from a .22-250 Remington felt like a .338 Winchester Magnum.

I figured Hornady 20-grain V-MAX bullets would pretty much drop out of the air after they reached 200 yards, but the tiny bullets surprised me. With the CZ sighted in 1.40 inches high at 100 yards, the bullets still hit an inch above aim at 200 yards. At 300 yards they dropped 5.50 inches. That meshes closely with Hornady’s 200-yard zero figures: +1.1 inches at 100 yards and -6.40 inches at 300 yards. So with some hold-over aiming finesse, the .17 would make a decent ground squirrel and prairie dog cartridge out to 300 yards.

It’s not a spectacular cartridge, though, because a hanging steel plate at 300 yards didn’t even move when shot with the tiny V-MAX bullets, but the approximately 200 foot-pounds (ft-lbs) of energy the little bullets still carry at 300 yards is enough to kill a ground squirrel.

After shooting 80 Hornady loads one afternoon, I soaked the CZ’s bore with solvent for a day and then gave it a good scrubbing with a bronze brush. Patches pushed through the bore came out with the black gunk of powder fouling but no blue color to indicate jacket fouling.

Handloading the .17 Hornet

The choice of .17-caliber bullet weights is rather slim. Most common weights are between 20 and 25 grains. Berger used to make 20-, 25- and 30-grain hollowpoints but now offers only 25-grain bullets. Hornady has been committed to .17-caliber bullets for decades and makes 20- and 25-grain V-MAXes and 25-grain hollowpoint .17s. Nosler offers 20-grain Varmageddon bullets with either a hollowpoint or plastic tip. Powder choice is also rather limited, with Hodgdon listing loads with six different powders.

The .17 Hornet’s tiny bullets and a small case capacity mean velocities vary considerably with a slight change in powder weight. Hodgdon’s load data shows 11.0 grains of H-4198 gave the 20-grain V-MAX a velocity of 3,226 fps. An additional 0.8 grain of the powder increased velocity by 237 fps. One of my handloads with 9.5 grains of Lil’Gun gave the 20-grain V-MAX a speed of 3,500 fps. An additional 0.5 grain of Lil’Gun increased the velocity of 20-grain bullets by 198 fps. Hodgdon lists as little as 0.3 grain between minimum and maximum powder charges for the .17 Hornady.

The powder weights for all the loads but one listed in the table were weighed as precisely as I could on a balance scale. Still, extreme velocity spreads ranged from 104 to 368 fps with IMR-4227, 142 fps with Reloder 7 and 162 fps with H-4198 shooting 20-grain bullets. Lil’Gun delivered much lower extreme spreads of 45 to 69 fps. As a comparison, the extreme velocity spread was 108 fps for 10 shots of Hornady’s Superformance Varmint 20-grain load. The heavier bullets had much lower extreme spreads, with 43 to 45 fps for the 25-grain bullets and 30 to 66 fps for the 30-grain bullets.

Hodgdon Lil’Gun is the powder for the .17. Ten grains gave 20-grain bullets a velocity of nearly 3,700 fps, which is all you can expect from such a small amount of powder. A 9.5-grain charge of Lil’Gun shot five 20-grain Bergers in .78 inch at 100 yards. The same charge with 20-grain V-MAXes started out with an even tighter group, but I flipped out the bullet from the fourth shot, which enlarged the group to 1.09 inches at 100 yards.

H-4198 was also a good powder. It attained the second highest velocities with 20-grain bullets and the highest velocities with 25-grain bullets. I don’t know how Hodgdon fit 11.8

grains of H-4198, as listed for 20-grain bullets, in cases, however. Even poured from a funnel with a long drop tube, I could only fit 11.5 grains of H-4198 in a case. Even then, a small mound of powder protruded above the case mouth. The powder did compress with no undue pressure on the press handle while seating bullets.

Hornady Custom Grade full-length dies were used to size and load the .17s. Cases did stretch some during firing and then sizing. Cases from unfired Hornady factory loads had a length of 1.338 inches, which I used as a trim length. After firing the factory loads, case lengths had stretched to 1.343 inches. Neck sizing the cases stretched them to 1.344. After the cases were trimmed, loaded and fired, they had not grown in length any appreciable amount. Full-length sizing the fired cases, though, lengthened them .006 inch.

Full-length sizing is fine if you want cartridges to headspace off the .17’s rim, but that amount of sizing set the case shoulders back .005 inch, which can cause cases to split around the web after firing them a few times. To barely bump back the shoulders of cases and set headspace on the shoulders, I turned the size die up a partial turn from contacting the shellholder. That partial, full-length sizing helps reduce the stretch of firing and the squeeze of sizing to extend case life.

The .17 Remington Fireball introduced a few years ago is a somewhat larger edition of the .17 Hornet, but the Fireball is less than trendy. I’m betting the .17 Hornet will hang in there, however, because it has a ready-made home as any gun chambered for the .22 Hornet can also be chambered for the .17. Plus, what’s not to like about a cartridge with a near absence of recoil that shoots flat enough to take small game out to 300 yards? I’ve been wrong before when predicting the cartridge-buying habits of small game hunters, but I hope I’m not wrong about the .17 Hornady Hornet.