We Were There Too: the US Army at Belleau Wood

The troops that took Vaux

An advertising agency is a good thing at times, but when the advertising agency misrepresents its goods there is a possibility of it becoming a detriment to the advertiser. There are a few organisations in France that really do not need an advertising agency- their work has been honourable enough to speak for itself. There are two regiments of Marines in France and they are part of my division and I know their service has been honourable, let us say just as glorious as many other infantry organisations of the United States Army that are now in France.

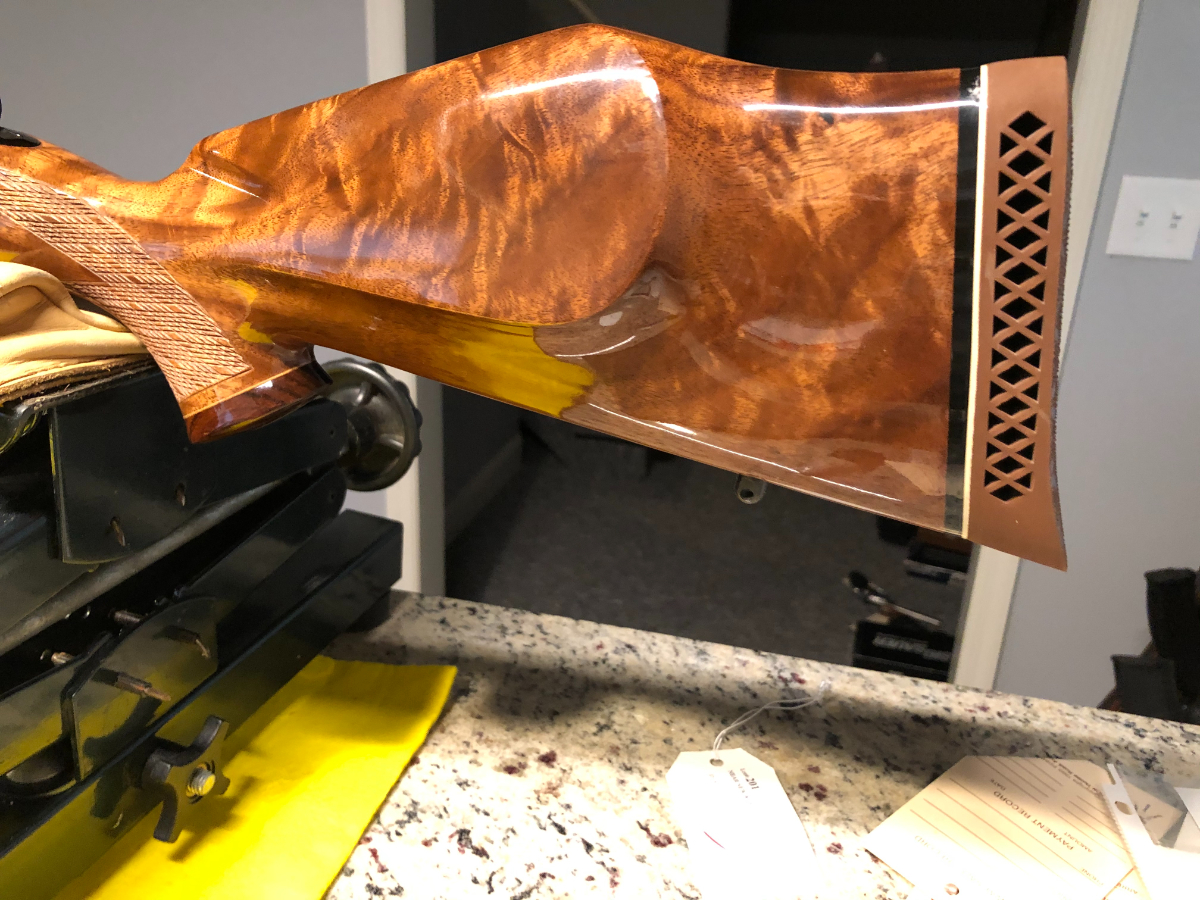

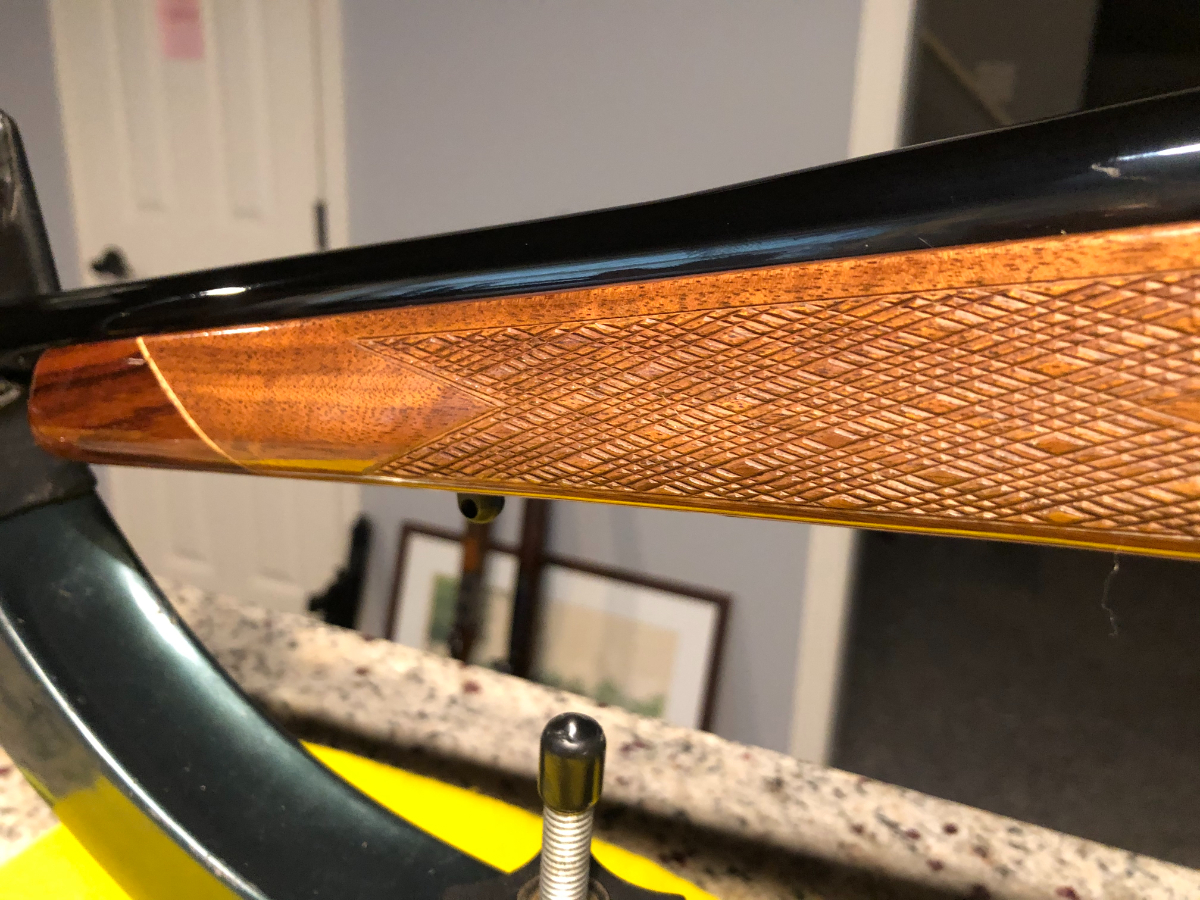

But from time to time, and very often too, certain papers in the United States write as if certain organisations were doing the whole thing alone over here. For example, in your pictorial issue of Aug. 11, 1918, you show a picture of the town of Vaux, France, and announce that this town was stormed by the marines. Now, as I am in command of the battalion that actually took Vaux and as we are all very, very proud of her reputation and of her high standard as a shock outfit, will you kindly correct this error? Also, out of respect for the high standard of veracity The New York Times has ever maintained, please remember that there are today over 1 750 000 American troops abroad, and about 6 000 of them are marines in the two excellent regiments the Navy Department has sent over.

George C Bowen, Major,

9th Infantry, HQ 2nd Battalion

Sept. 24, 1918

With the shots of the First World War far from over, the question of who had accomplished what in this most recent conflict was already a hot one.

For the first state dinner of his presidency, President Trump could hardly have picked a better candidate in this centennial year of U.S. combat action in World War I: President Macron of France. And for a gift to the United States, Present Macron could hardly have picked a better symbol: a sapling from Belleau Wood, or as it is now known, Bois de la Brigade de Marine (Wood of the Marine Brigade).

After World War I, a grateful French nation gave the ground of Belleau Wood to the United States – as well as all the land containing American cemeteries – and changed the name. It was now named in honor of the Marine Brigade which had fought so hard to take the two square kilometer wooded height in the heady days of June, 1918 when it was rumored that all that stood between Paris and the dreaded Hun was the thin line of Marines.

And as well they should. And well should the Marines be proud of their 5th and 6th Regiments and 6th Machine Gun Battalion, which formed the Marine Brigade, part of the Army’s 2nd Division. Well should the Marines still visit the site yearly and pay honor to the Leathernecks that went before them.

But this piece is not for the Marines; it is not to take anything away from them. This is for the Army. Specifically, the 2nd Infantry Division. And the message is this: step up, didn’t you know you were there too?

Because while the saga of the Marines is well-told and familiar to most who know anything about World War I, the 2nd Division – and the Army as a whole – have seen fit to sit back and let the Marines take ownership of the entire Belleau Wood affair. Which is unfair to the Soldiers of the 9th, 23rd, and 7th Infantry Regiments, the 4th and 5th Machine Gun Battalions, the 12th, 15th, and 17th Field Artillery Regiments, the 2nd Trench Mortar Battery, the 1st Field Signal Battalion, and the 2nd Engineer Regiment – some 18,000 troops in all..

This is their story.

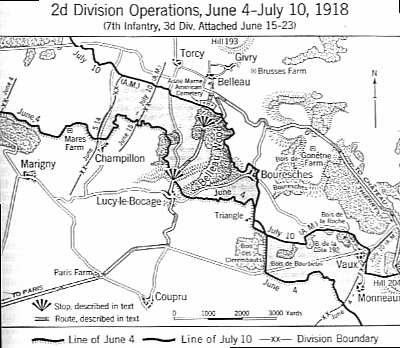

By June 5, 1918, the 2nd Division’s lines had finally stabilized after several hectic days of relief and defense during the waning hours of the Aisne Defensive (Map of sector – use this to navigate the sometimes complex battlefield). In that time, the infantry and machine gun units of the division had been thrown into the line where needed as the Germans advanced and the French slowly withdrew, fighting for every town and wood. With a lull, the US and French were able to reorganize their front. On the left, near Champillon, the French 167th Division extended its lines to allow the 5th Marines to consolidate around the Bois de Champillon and close up to the 6th Marines near Lucy-le-Bocage, south of Bois de Belleau. The Marine Brigade was now situated to strike at the German defenses in Bois de Belleau from the west and south, catching the height in a vice grip.

Just northeast of Lucy-le-Bocage is the town of Bouresches, less than a two kilometer distance. The town controls a number of roads that provided access to both German and U.S. lines of supply. One kilometer south of Bouresches is Triangle and one and a half kilometers south of that tiny community is the small village of Le Thiolet. Two battalions of the 23rd Infantry took over the line from Triangle to Le Thiolet, facing almost due east. The 9th Infantry occupied the front running east from Le Thiolet to Bourbetin down into the woods of the Bois de la Morette where they linked the division’s right flank to the French 10th Colonial Infantry Division.

The front was a mess of wheat fields, small towns, and woodlots, with parallel ridges facing each other. It was virgin territory, the ground as-yet unscarred by trenchlines and shell holes. This would all change in the coming month.

The division’s artillery was arrayed behind the lines in support of both infantry brigades. Two 75mm regiments provided direct support to the embattled Doughboys, while one regiment of 155mm heavy guns delivered the long-range punch needed on the World War I battlefield. The hardy 2nd Engineers would be piecemealed out to the Marines and Infantry alike to aid them in their attacks. When not digging in, the engineers fought alongside the Marines as infantry.

The 2nd Division had been given two missions: capture the height of Bois de Belleau and the nearby town of Vaux. The height was in the sector of the Marine Brigade while Vaux lay far to the right, nearly on the dividing line between the French and the 2nd Division. The division took it one thing at a time and made the Bois de Belleau the priority mission. Vaux would have to wait.

On June 6, the Marine Brigade began their attacks on the Bois de Belleau and Bouresches, accompanied by the 2nd Engineers. One of the engineer battalion commanders had the following to say about what he learned in this operation (full account here):

Serving with infantry as infantry, has two very considerable advantages. It gives the engineers more prestige than anything else they can do. After the infantry discovers that engineers can fight, they are usually much more willing to cooperate on engineer work, and line and staff officers are usually more willing to recognize the value of an engineer regiment. Furthermore, the effect on the morale of the men is excellent, it makes them easier to handle on any work that has to be done under fire. But the practice must not be carried to such an extreme as to seriously interfere with the work the engineers must do.

The 2nd Battalion, 2nd Engineers assisted the 5th Marines in taking Hill 142 and played a vital role in its defense, fighting off German counterattacks. The 1st Battalion accompanied the 6th Marines into Belleau Wood where they took part in the first assaults.

At the same time, at around 6 pm, the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 23rd Infantry advanced from their positions to come just south of the road leading from Bouresches to Vaux, a distance of about a kilometer, in an attempt to cut Bouresches off from German reinforcement. About two hours after advancing, the 3rd Battalion was hit with a heavy counterattack in the vicinity of Cote 192, where they suffered extreme losses. Just after midnight, both battalions were given the order to withdraw to their starting positions.

To the right, the French 10th Colonial Division surged forward against a German height and the 9th Infantry extended their lines further to the right to support this assault. 2nd Battalion, 9th Infantry advanced east of Bourbetin, seizing a height above the Bois de la Morette where they dug in, expecting an enemy counterattack at any moment.

From this point until July, the Infantry Brigade had little of note occur. But that didn’t mean they did nothing. Holding a front line position meant aggressively patrolling the front, sending out raids to keep the enemy off balance, digging in, and sucking up an insane amount of enemy artillery shells. Which is what the 9th and 23rd did for most of June, gradually extending their lines to the left to allow the Marines to consolidate around Bois de Belleau.

On June 7, the 2nd Engineers assisted the two companies from the 5th Marines in the seizure of the woods southwest of the village of Torcy. These clearing operations were meant to close the loop around Bois de Belleau. The 2nd also assisted the 6th Marines in taking Bouresches and 110 engineers held the front lines with the Marines, fighting off German counterattacks. Over on the right flank, the Germans attempted to break through the 23rd Infantry around Triangles, striking the left flank of the 9th Infantry as well. This assault – taking place just after midnight on June 8 – was repulsed. Dawn attacks in Bois de Belleau by the 6th Marines and 2nd Engineers did little to advance the front. The troops were pulled back to allow artillery to soften the targets.

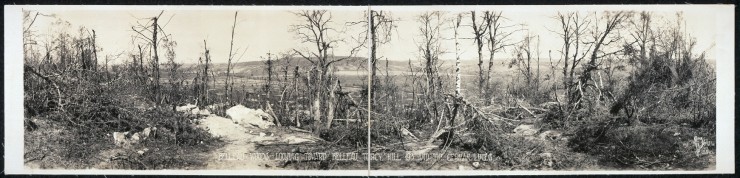

Like most of the US divisions, the 2nd Division came to war with forty-eight 75mm guns, twenty-four 155mm guns, and twelve six inch trench mortars. These all began to play on the small area of Bois de Belleau, high explosive shells shattering trees and burrowing into the earth before exploding in gouts of fire and shock. Much of June 9 and 10 was spent in pulverizing the German positions in the woods, trying to seek out and destroy the hidden machine gun nests. In all, the division fired 40,000 shells in this preparation. The guns fired their last salvos before transitioning to a creeping barrage on June 11 to support the Marines as they attacked from Lucy-le-Bocage. The Marines got into the woods and lodged a foothold, reinforced by Companies D and F, 2nd Engineers.

June 12 was another busy day for the artillery, again pounding known and suspected German positions on the Bois de Belleau. All units participated in defeating a German counterattack on June 13. Company D, 2nd Engineers was deep in the woods with the Marines when the counterattack happened and all soldiers dropped their shovels to help fight off the attack. 1st Lieutenant Lyman Chase of Company D, 2nd Engineers then led his platoon in a successful assault on a German machine gun position.

On June 14, the front was adjusted to allow the Marines to again compress their forces around the Bois de Belleau. All three battalions of the 23rd Infantry went into the line, taking over the eastern edge of Bois de Belleau and the entirety of Bouresches from the 5th Marines and extending down to Tuilerie de Triangle, where they connected with the 9th Infantry. The following day, the front of the 2nd Division again compressed, for the same reason. The French 167th Division on the left relieved troops from the 6th Marines, allowing both Marine regiments to consolidate their shrinking battalions. The 23rd Infantry fought off a weak German counterattack on the east edge of Bois de Belleau and at Bouresches.

But after ten days of near-constant advancing in terrible conditions, confronted by a determined, well-trained, veteran foe, drenched in gas, the Marines needed a break. They had suffered more casualties than the Marine Corps had ever suffered in all of its previous battles, combined. Enter the 7th U.S. Infantry Regiment, on loan from the 3rd Division. All three battalions went into line from June 16-17 replacing the Marine Brigade in Bois de Belleau. From this time until June 21, the regiment ground away at the stubborn German defenders, slowly bringing the lines closer in on the wooded hillock. In attacks both with and without artillery preparation – attempting to use surprise – the 7th was unable to get much farther than the Marines. But they kept the pressure on the Germans, never allowing them time to improve their forward positions. In addition, these 5-7 days gave the Marine Brigade time to fill their depleted ranks with replacements, get some breath, and rearm for the final push.

On the night of June 23-24, the Infantry Brigade was hit with a German gas attack; mustard gas shells mixed with high explosives caused over four hundred casualties and necessitated the evacuation of many wounded. The commander of the 23rd Infantry’s machine gun company wrote to the regimental command post: “After the gas attacks last night and this morning I have not enough men to man my guns and hold the position.”

Local attacks continued in Bois de Belleau, but with little to no progress. This changed on June 25. From 3 am to 5 pm, the three artillery regiments of the division pulverized the northern sector of Bois de Belleau. When the barrage lifted, five companies of Marines assaulted through in heavy fighting that lasted into the night. But the artillery had done its work well – this time the Marines took and held the ground. Mopping up operations remained, but the 2nd Division had finally taken their main objective.

But all their work wasn’t done yet. There still remained the problem of the village of Vaux which was a German-held town poking down into US and French lines. It interrupted lines of supply and communication and prevented the Allies from being able to get a good line of sight into German lines. It would have to be taken. But taking it would be no easy matter, since the Germans were holed up in all eighty-two of the strongly-built stone houses. Fortunately, the French knew the stonemason who had worked on all the houses and he was able to provide drawings of each building. Aerial reconnaissance revealed some German machine gun positions. Soon they were able to get a good idea of what they were up against.

For the infantry brigade, cooped up to the south of the Marines, this would finally be their chance strike back. For most of June, they just had to sit and take it as their lines were saturated with gas and pounded with artillery. Now it was their turn to see if they were as good as their Marine brethren.

The artillery began a twelve hour bombardment at 5 am on July 1, the barrels of the well-worked guns now pointing towards Vaux, just to the front of the Infantry Brigade. They were joined by twelve batteries of French artillery, all pounding Vaux and the daunting Hill 204 to the east, which was the French objective. At around 2 pm, four batteries of US artillery fired mustard gas behind the objective to prevent reinforcements from moving in. But this fire was not without answer: the German guns fired about 33,000 shells around Vaux that day in an effort to break up the expected attack. They were unsuccessful.

At 5 pm on July 1, the US barrage grew in intensity as the infantry assembled in their jumping-off positions. With three minutes to 6 pm, the barrage transitioned to a rolling roar of shells, clearing the way for the infantry. The 2nd Battalion, 9th Infantry crashed into and rolled over the German defenders in Vaux, taking 440 prisoners, while the 3rd Battalion, 23rd Infantry seized the tree-covered heights to the left of the town. The Germans attempted to wrest Vaux away from the 9th Infantry on the morning of July 2 but were soundly defeated, losing another 141 prisoners. With Bouresches and Vaux now in friendly hands, the left flank of the division was secure from German assault. They had set the stage for the next piece of the operation: counterattack.

The execution of taking Vaux had been near flawless. The 2nd Division had learned from the bloodbath on June 6 when the Marines rushed into the meat grinder without waiting for artillery preparation. The attacks of June 25 and July 1 demonstrated that with adequate planning and preparation, relatively small numbers of troops (1-2 battalions) could take and hold ground with acceptable casualty levels. Ground which larger numbers of troops would find impossible to take without losing significant numbers of troops.

By Independence Day, the 2nd Division could now hand off a secure piece of the line to the incoming 26th Division. They had taken over the dominating heights and vital supply lines needed for the US to be able to continue the advance against the strategically important Etrepilly Plateau. But it had come at a severe cost. The 9th Infantry had come out of it the best, with 158 dead. The 23rd Infantry had 307 dead. The 5th Marines, 421; the 6th, 215. The 2nd Engineers had 121 men killed. In its three or four days of combat, the 7th Infantry had 93 men killed. And of course, there were many thousands of wounded. All told, the division had suffered nearly 8,000 casualties in one month of combat.

Today, Belleau Wood stands as a visible example of America’s commitment to the war. The operation was truly “joint,” between the Army and the Marines – with Navy corpsmen. All branches fought side-by-side to complete the mission, with one Marine saying, “Say, if I ever got a drink, a 2d Engineer can have half of it! – Boy, they dig trenches and mend roads all night, and they fight all day!”

And yet…when you go to Belleau Wood, you’ll see pretty much everything dedicated to Marines. Almost anyone who visits is there for the story of the Marines. If you look really hard next to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery, you can find a small marker to the 2nd Engineers, and there’s another hiding in Belleau Wood. Across the street from the cemetery is the 26th Division Church, dedicated to the division that took over from the 2nd and drove the Germans back nine miles. But that doesn’t get much play.

And because the Marines overshadow the Army in the battle, it often impacts the historiography of the battle. Take the iconic photo of the battle used as the cover photo for this piece – four visible Americans, two manning a 37mm gun, one slowly rising to his feet, one charging forward, bayonet fixed. All amidst a blasted hellscape. Devil Dogs at work. Except they’re not. They’re members of Headquarters Company, 23rd Infantry Regiment. Yet it is constantly shared as a Marine Corps photo.

And then there’s the Devil Dog fountain.

A stop for every Marine who visits Belleau Wood, the Devil Dog fountain is part of an old chateau in the town of Belleau, destroyed after the war. The fountain is in the shape of a German mastiff head since the chateau’s owner was probably Alsatian. Marines, seeing this after the war, called it providential, that this was their very own devil dog (although Marines, not Germans, developed the term, it caught on very quickly). Why did they not see this until after the war? Because Belleau was inside German lines in the time that the 2nd Division occupied the sector and would remain so until July 18, eight days after the last elements of the 2nd Division left.

So as we approach the centennial of the intense combat in June, I’d remind the 2nd Division and the U.S. Army that Belleau Wood is your battle as well. Stand next to our Marine Corps comrades and be proud of what the Doughboys and Leathernecks accomplished against stiff odds 100 years ago, just as we do today.

Enjoy what you just read? Please share on social media or email utilizing the buttons below.

About the Author: Angry Staff Officer is an Army engineer officer who is adrift in a sea of doctrine and staff operations and uses writing as a means to retain his sanity. He also collaborates on a podcast with Adin Dobkin entitled War Stories, which examines key moments in the history of warfare.

Cover photo: Gun crew from Regimental Headquarters Company, 23rd Infantry, firing 37mm gun during an advance against German entrenched positions (Library of Congress)